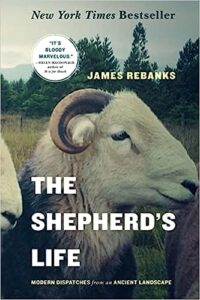

| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: June 7, 2023.] Russ Roberts: Today is June 7th, 2023, and my guest is author and sheep farmer James Rebanks. Our topic for today is the life of the sheep farmer depicted in his first book, The Shepherd's Life, which was published in 2015, but we may also get to his 2020 book, English Pastoral. James, welcome to EconTalk. James Rebanks: Yeah, thank you for having me. Thank you for having me. |

| 1:00 | Russ Roberts: The Shepherd's Life is an incredibly beautiful book about what it's like to raise sheep, about what it is to be a son to a father, and the father to a daughter or a son, and what it is to be close to the land, and the course of daily life. It's quite moving and it's unbelievably informative for most of us who don't know much about sheep farming. So, our goal today is to try to give listeners some idea of what that's about. And, I'm going to start with the fact that your family has been in the same general area, which is the Lake District of England, for a very long time. Tell me how long they've been there? What did that mean to you as a boy growing up, and what does it mean to you today as a man? James Rebanks: Okay. So as I talk to you right now, I'm basically sitting in my barn. I've got a nice office in one end with a computer and windows 'round, but it's basically an agricultural barn. And, I'm looking out over the valley where I live, which is Matterdale in the English Lake District. And, yeah, my family have been here for a very long time. We've got paperwork direct--my direct descendants were here to at least the early 1600s in the same very small village. We've got records of people with the same name 200 or 300 years before that. So, you're, like, 600 years back in the 1420s. But interestingly, journalists keep saying that my family turned up here in the 1420s. No, just that's when the paperwork starts, the historic archive begins. So, it may well be that we were the kind of people that lived in this area for maybe a thousand years before that, maybe several thousand years before that. Who knows? But, we were--and I had to research this when I started to think about writing my first book. When I looked into it, we were basically small farmers, almost peasant farmers, and we would bounce around between sometimes what looks like pretty horrible poverty. So, you can find the younger brothers and sisters in the work houses, like where the poor were sent. But in the good moments, I'm guessing the older brothers who got the farm under primogeniture--I think that's what they call it--some of them were established farmers, and they get mentioned in other documents. Like, there was a thing called the yeomanry in Britain, which is that the very large aristocrats want a sort of middle class bunch of tenant farmers to get on horses and fight with them when they need someone to fight. And, it looks like the more affluent members of my family became established farmers, and they occasionally did that and they would fight the Scots or they would put down riots of industrial workers or whatever that might be. It was very feudal, and we were bouncing around--not on the bottom rung, but just above that really, occasionally dropping off the ladder when things got bad. So, what does that mean to me? Well, it would just be academic, I guess, but the work that I do on the farm--so, I'm a sheep farmer on the farm that my father and my grandfather lived on, not far from where we've lived for all of that period of time. And, it's absolutely alive all around me. So, the work I do is a continuation of their work and a continuation of everybody's work before me. So, the flock of sheep I take to and from the mountain, we think--the sort of genetic science tells us that they're at least a thousand years old. There's some Viking sheep genetics in there, which means the same job I did last week of taking the sheep--the mother sheep, the ewes and lambs--to the mountain, that's been done by somebody every single spring for at least a thousand years without any break. There's no war, farming, any kind of big historical event that's sufficiently damaging to stop that happening even once. So, that's had to continue for the whole period, at least a thousand years, maybe four and a half thousand years. So, it's been absolutely about hanging on, and it's absolutely alive. I can't forget about it because it's all around me. I pick a stone up to repair a stone wall or a stone dike, and it's been picked up by somebody who is either one of my ancestors or somebody like us who did it before. I work with the sheep: it's something that somebody's done a thousand times before. And it's, I think, a lot of modern thinking--and we can talk about this later--a lot of economic thinking that[?] centers on the individual and the individual's happiness or the individual's utility. And, I became more modern when I got into my twenties and had a slightly different life. But, when I came back, what really struck me was: I'm not very important. Me, as an individual, I'm not very important. Yes, I've written some books and people want to focus on me as an individual, but really I'm in a very long chain of people. Hopefully a chain that stretches on far into the future. I'm quite insignificant. The sheep were there at least a thousand years before me. The mountain was there for millennia, forever before me. The work goes on in cycles. It makes you feel quite small. But, I'm not crushed by that or disappointed by that. I find that good, really. I think it's humbling in a good way. It reminds you just how small you are and that history and life and nature, these things are much longer lasting and much bigger than any of us. |

| 6:09 | Russ Roberts: But, I think in modern times, we're encouraged to think of ourselves as a blank slate that we can write our own story on. I'm an interesting case. I was born in Memphis, Tennessee. My family left there after a year. I grew up mostly in Boston, outside of Boston, Massachusetts. But, my parents were Southerners. They didn't fit in. They had a thick southern accent. My friends made fun of them. And, here I am, crazily, in Israel: I came here at the age of 66, 2 years ago, to what is the Jewish homeland, a place where we have been for, off and on--mostly on, I think in smaller or bigger numbers--but, we've been here for 3000 years. And there's something incredibly humbling, as you say, about realizing that you're not a very big part of a very long chain. But, you are part of a chain. And that creates, I think, for me, and I'm curious for you, a feeling of belonging that is otherwise missing, I think, in a great many ways in modern life, for at least the educated folks who fly to where the jobs are--say, with the highest pay or the most the most self-expression. That's fine. And, I don't have--it's something tawdry about that. But something has been lost in our interest in cutting ourselves off from our roots, I would argue, and seeing ourselves as a blank slate. Do you feel that, or do you disagree? James Rebanks: No, I do feel that. And, I'm always aware that although my family weren't wealthy, there is a kind of privilege in having that sense of belonging. There is a kind of privilege to live on a farm in the Lake District, which has this long history. The Industrial Revolution meant that most people lost that connection to a place. They were uprooted, they were taken to cities. So, I would never want to sound preachy or, as you say, sort of judging people down who don't have what I have. But, yeah, I distinctly remember--and I wrote about it in my first book, The Shepherd's Life--I distinctly remember being at secondary school where they thought that we were blank slates. And quite disappointing blank slates, because we were farm boys and girls or factory workers' or hairdressers' kids. And they thought that they wanted to imprint on the blank slates that we should leave: we should go to London, we should go to Oxford, we should go to Cambridge. Actually, they never mentioned those two places in my school. But the general idea was you were meant to leave and become somebody. And, becoming somebody meant not being a worker, not being provincial or small-minded, not being yoked to the place and thinking that was the most important thing, but pursuing your own self-development, pursuing ideas, pursuing wealth, whatever it was. But, it was always somewhere else. It was beyond the horizon in the place that the clever people went to. And, I remember hearing this--and they sort of wanted that for me because in my moments where I did work hard at school, I was probably quite good at school. And they saw that. But I wouldn't engage. And, for me, it was because they were asking me to do something that felt like a betrayal and also something that didn't make sense. So, they were implicitly saying to me, or I felt they were, that what my grandfather was--he was basically a sort of small peasant farmer or sort of small yeoman[?] farmer, maybe more accurately--that he wasn't anything. He wasn't a someone. He was a nobody. And, I remember being enraged by this, because it's both illogical and unfair--and blind. So, I would hang out with this old man who is my grandfather, and he was wise and clever. He knew all of the wildlife around him. He knew all the people in his community. He was respected. But it was somehow all beneath their gaze, beneath what they thought was important. And, many years later when my life changed a little bit and I realized that maybe I could write something, write a book, I was sort of channeling that feeling. I wanted to tell the people that read books--I'm like, 'Whoa, hang on a minute. Yeah, screw you.' Slightly rude language. I wanted to push back against that and use whatever talent I had for telling a story to say, 'No, you don't see me.' Like, I remember reading this--I think there's a guy called Tzvetan Todorov[?] who writes about the conquest of South America. And, he said, 'The conquistadors discovered the Americas, but they didn't discover the Americans. They couldn't see them. And, because they couldn't see them, you can then, at its mildest, ignore them or overprint them with your own culture. At its worst, you can displace them, take their land, and ultimately kill.' And, I think we see that all around the world. And, my family luckily weren't exposed to genocide, but they were sort of overridden in a cultural sense. So, anyone who knows about English culture will know that the Lake District is this iconic literary landscape that's hugely important to the English, but it's not the story of my people, who live in it. It's a sort of middle class, poetic, romantic fantasy. |

| 11:22 | Russ Roberts: And of course, people who come visiting as tourists, see you and your family as players in a drama that they consider--as you're suggesting--it's a minor role. You just happen to live there. They're glad you're there in your cute outfits and your boots and your muck, but you're there for--the waste[?] in a diorama in a museum, there would be people in native costumes and so on. And, there is certainly a lack of respect. I can't help but think of Adam Smith's line in the Theory of Moral Sentiments, where he says, 'Man naturally desires, not only to be loved, but to be lovely.' And later he says, 'The chief part of happiness is being beloved.' And, he doesn't mean romantic love. He means being respected, being seen as someone significant, mattering--a person to be honored. And, Smith says there's two ways to do that. And, we're recording this very shortly after the 300th anniversary of what we think is Smith's birth. So, I'll just throw that in. But, Smith says, 'There's two ways to matter. There's two ways to be significant. One way is to be rich, famous and powerful, or one of those three. The other is to be wise and virtuous.' Now, your grandfather was wise and virtuous. He wasn't rich. He's certainly not famous, certainly not powerful. And, that outside world that comes to the Lake District and looks at him, sees an uneducated man--as you suggested earlier--who has not really made anything of himself. But, what you saw, as a boy, and what you write about beautifully in your books, is you saw a wise man, also a virtuous man--not always--he's a human being of course. But a person who had a code, a very strong code, of how to treat animals, how to treat the earth; and how to treat your neighbors, and in return was respected deeply by his social circle. It was a small social circle. He didn't have a lot of followers on Facebook or Twitter. But he mattered, in his world. And, I think what I hear you saying--which is very powerful--is that when you went out into the rest of the world, you realized that the rest of the world--you write about you went off to Oxford, which is a sweet story--but that world of Oxford, that intellectual world, did not respect the intense and deep knowledge that your grandfather had, because it wasn't the kind of knowledge that Oxford cared about. And, that is really fascinating. James Rebanks: So, I need to tell you something. So, you're right, he didn't have social media to have a mass global following. But, can I tell you something, which I'm very proud of? Despite no one ever hearing of my dad or my granddad who were both farmers, when they died they couldn't fit everybody in the church. There's like 450, 500 people turn up. And, some of that's because they went to everybody else's funeral. And, we have a very close community and it's reciprocal. And, some of it's just a very quiet respect from working people for other working people, or because he's lived by a code. And as you say, it wasn't perfect. I don't think he was a particularly good husband. And, my grandfather may not have been a very good father. But in terms of somebody who lived in his community and lived by a certain code, yes, there's a lot of respect there. And, I think what really shocked me: when I got into my twenties and I started to read more, and I started to understand the wider world more--because circumstance threw me out into that world, really--was if you're not in books, if you're not in books particularly, but if you're not in books and films and radio, you don't exist in the modern mind. You are some[?] out with the culture. And, as somebody who loved books, I latched onto that. I'm like, 'Okay, there's a way to change. If you want to be seen, you have to write the book.' And, I spent nearly 10 years looking for somebody else having written the book. I kept going in bookshops saying, 'Where's the book about my granddad and about the people that do this work?' And, Wordsworth and other people nearly did it. They were looking over at these people saying, 'There's something interesting here.' But, they weren't [?] that thing. They weren't the son or the grandson of that shepherd. So, yeah, it's a fascinating thing. And, I have to say, I was very, very influenced and still am: I love lots of immigrant writers, people like John Fante in America who is, like, an Italian immigrant, or more recently people like Junot Diaz who are--I think they call it writing back against the dominant culture. It's sort of fighting back against sort of colonial mentalities, fighting back against class, and just doing that with the power of story, really, saying, 'You're going to look at me. You're going to look at my people.' And, yeah, I have a huge amount of sympathy with people in all kinds of minorities or people who feel like they're outside of the dominant culture and are fighting back culturally. That, to me, was very powerful, to realize you could do that. Russ Roberts: Well, it's clearly part of the tension in the political environment in today's world. You have people who feel they've been marginalized by the elites, the experts, the educated classes--whatever you want to call it. It's driving a lot of populism. Obviously it drove a lot of political change in the United Kingdom, the United States, and many other places. |

| 16:59 | Russ Roberts: But, let's move on to--and I want to reference the episode we did with Megan McArdle on Roger Scruton's book about home. And, I think home is a thing that many modern educated people don't have. You know--I suggested earlier--I didn't feel at home in St. Louis, Missouri where I taught at Washington University. It's a lovely town. It wasn't my home: just where I happened to live for 14 years. Somewhat my home, because I raised--all my kids were born there, so it was kind of their home for a while. But, that connection that you have is really obviously very rare in that magnitude. But, you don't need it to go back to even 1600, I think, for many people to feel it. You want to add something? James Rebanks: Yeah, I do, really. Isn't what you're talking about--I know it happens all around the world, but it feels to me like a particularly American experience. So, the American historic experience was, your home isn't the most important thing because there's stuff wrong with it--they're stopping you worship your own God, that's stopping you living in the way that you want to. You're too limited, you're too poor by these unfair structures. Come to America. Place isn't the defining thing. You can move west, you can move east. You can-- Russ Roberts: Yeah. James Rebanks: And, I know when I talk to Americans--and I'm not judging this on unfairly, I understand why it's like that--they've often lived in two or three places. They're not sort of typically rooted to one place, or if they are, it's only for a generation or two. When I talk to Italians or maybe people in rural France or I don't know, people in Asia or Africa, that's quite different. That one of the defining things in their identity is place. 'Well, my people are from here.' Yeah. Russ Roberts: Yeah. No, it's fascinating. |

| 18:48 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about being a sheep farmer. What's fun about your book is, I would describe it this way: There are a lot of bad days and there are a lot of good days and you don't really pay any attention to the absolute number. You don't need 183 good days versus 182 bad days to make it a good life. It's just the whole thing is one fabric, one texture. And, the bad has to come with the good because it rains and you have to be outside. And, sheep are difficult and they get diseases and they die and they get attacked. And, it's just part of life. So, give us a couple bad days, things when it's hard to be a sheep farmer; and then a couple good days. James Rebanks: So, I'll try not to make it all sound good. Russ Roberts: No, not fair. James Rebanks: No, no, I won't. So, I won't do that. Being a sheep farmer at times is a little bit like being a nurse or a doctor. You go to work, you pitch up and you get punched in the face with reality. A lamb is dead on the ground. Its mother has given birth to a dead lamb. You got there 10 minutes too late because you went to the other field first and you'll never know whether if you went to that field instead you might have saved it, maybe the 10 minutes. So, there's a lot of responsibility that's very elemental. It's about life or death. And, by definition, you can't get it right all of the time. So, there's a degree of self-blame on the bad days, 'Why did I do it that way? Why did I not do it the other way?' And, you want to believe that you are some kind of benign god for your flock and keep everything alive and make everything okay. But of course, you can't, because it's nature. So, the bad days, for me, are maybe when we're at lambing time and it's just the really bad day when everything goes wrong. The mother gives birth on the side of the stream or the beck, and the lamb falls into the water and drowns. And, you know, 'Why would you do that?' And, 'Why was I not there to stop it?' You can have--all sorts of physical things can go wrong with lambs when they're born. They can die in the birth sack, in the fluids, and never breathe. Occasionally, rarely, the insides can come out through the navel because the mother has tugged at the navel--being overly motherly--and pulls the insides out there. Pretty grim things happen like they would on a sort of a E-ward [emergency ward], like a doctor's ward. And, you're just doing the best you can. And, that can be tough. Sometimes you come back in the house and you think, 'I got everything wrong today. If I'd done all that the other again, I'd do it differently.' So, it's tough. Tougher than that, because I've done this my whole life. So, I got used to that stuff a long time ago. Tougher than that is something that farmers all around the world feel, which is, they don't see economics as impersonal. They feel it absolutely personally. So, you take over this farm that was your father's and your grandfather's. If you don't make any money or you're going broke, you're failing. We don't think the farm's failing, the economy's failing, the technologies have changed. We go to bed feeling absolutely crushed because the farm isn't really a business in our minds. It's an extension of who we are, an extension of our identity. And, the experience of the modern farmer is one full of debt and effectively being a price taker. What is the old joke: that we pay retail when we buy something and we sell wholesale when we sell something. We're never in control. The actual economics of farming is really quite crushing and depressing. And, I mean, the sort of 1970s economics on this work, Earl Butts--who was Nixon's Secretary of Agriculture--said, 'Plant corn from horizon to horizon. Get big or get out.' And, that would be okay if you won the game when you did that. But, you don't. You end up more trapped into a bad system, still powerless, still taking. So, in an economic sense, it's a very frustrating profession and often feels like it's stacked for you to fail. But, there's a lot to be said about. Russ Roberts: But, on the physical side--and we'll get to the good days in a minute--but the physical side is, you're outside. It's incredibly hot sometimes and you're throwing hay around, or it's pouring rain, it's freezing cold, it's snowing. It's a physically demanding life that your book really illuminates. James Rebanks: Yeah. So, this'll make you laugh, but I might--some people feel the cold worse than others, right? I do. I feel the cold really badly in my hands. That's insane. I have to go out on a lot of days in the middle of winter when it's cold and wet, and everything I touch is cold and wet, and I'm just not doing my job if I go back to the house and drink coffee all day. I've got to keep going, keep doing it. So, sometimes I'll come in to thaw out my hands. And, my pet hate--it's a little thing--my pet hate is that stinging feeling in your hands when you're trying to defrost them under a hot tap. And, in winter I'll end up with my hands swollen and cracked and, you know, 'Why am I doing this?' And, the winters here are sort of six months long. Now they're not super cold and super snowy, but they're cold and wet, rainy, really. And, that dampness is depressing. So, everybody here, the English people in general but definitely if you live here, you're very ready for spring. And, we are those people that are out with our shirts off on the first sunny day in May, because we're sort of sun worshipers because we have such a gray, miserable climate most of the time. But, you're right. The other side of that--and I wrote about this in the book--I don't think you get the highs without the lows. So, the fact that I do a hundred, maybe a hundred days on the trot in a bad winter in the cold and the wet, gives me a feeling of elation when I get to spring, that is higher than any other high I've had ever had in my life when the sun comes out and I've got through winter, I've kept all my sheep alive. But, I'm not sure if I'm describing this very well, but I think you need to have the lows, don't you, to have the highs? It's all about the contrast, isn't it? And, this life does give you both. It gives you the days where it nearly crushes you. And then--like, today I'm looking out the window as I talk to you--it is insanely beautiful and sunny here today. And, I've worked for two thirds of the day. I've been doing this with you and a couple of other things in the other third of the day. But, there's no way you don't feel lucky on a day like this. I've got beautiful views. I'm not in a city, there's no traffic. I'm one of the luckiest people on the planet on a day like this. So, it's all about trade-offs, isn't it? I can't ask everybody to pity me. That's not what I do in the book. I just try to describe the highs and the lows. And, it's interesting: I have a 11-year-old son called Isaac, and he's been a typical, typical day-dreaming, playing-around kid until about six months ago, just like I was at his age. And, I love that. I don't need him to be a farmer. And, then this spring he came with me to do the lambing; and he was obsessively coming with me like something's clicked inside him and he loves it. But, at the end of the six weeks while we're lambing--so, lambing is every hour and a half going out in the fields to check the lambs are alive, that things are where they should be, correcting any mistakes, keeping animals alive--he's a different kid after six weeks of doing that. He's just focused. And, now when I talk to him, I can see he's got the same, like, insane love for it already as I had at his age. It's going to be really hard to persuade him that you should go to college or you should become a doctor or an accountant or something. When I talk to him and say, 'Look, there's lots of things you can do. You can do this as well as something else,' he's already glazing over in his eyes as he looks at me, like, 'What are you talking about, Dad? Why would I not want to be there when the sun comes up? Why would I not want to hear the birds? Why would I not want to be part of this historic community? Why would I not want to earn the respect of all these people that live here? Why would I not want to be like you and your dad and your granddad?' And, I had a really bad case of that in my early teens where I just couldn't understand what the school people were on about. I was like, 'You people are crazy. You're telling me that my life's nothing? It's the best life in the world. You couldn't drag me away from this.' And, that's how I feel about it. I feel genuinely lucky. If I was to die tomorrow and you got to reckon up your life, I wouldn't regret a minute, not a minute of it. And, my dad actually did die of cancer eight years ago. And, I said to him when he was a few weeks away from dying, I said, 'What do you want to do? There must be something you never did. Do you want to go to a fancy restaurant or do you want to go see something you haven't seen?' And, he basically said, and he used some choice language, but he said, 'I want to come to work tomorrow morning and do what I've always done because I love it.' And, he did. For as long as he could. And, I remember thinking, 'Wow. Wow. Your life is exactly what you wanted it to be. And, how lucky are we?' I don't know what there is above that. |

| 28:04 | Russ Roberts: Well, there's a big debate--not a debate, but a big conversation, I think--that started in recent years and it's going to continue. It started really, I think, with the beginning of outsourcing--the worries that, in America, that all the jobs would go to China or Japan or Mexico, it didn't matter. There's always a different country to be allegedly afraid of. And, then it was driverless cars or now ChatGPT [Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer]: There's going to be mass unemployment. There are going to be millions and millions of people who won't be able to work, who can't do what they've been trained to do or the skill that they have been investing in. And, we're going to have to have some sort of Universal Basic Income to take care of people who are no longer able to contribute to the world around them. And, I don't know if that's going to happen. I think some of those fears are grossly over overblown. But, it could happen. And I think what fascinates me is, economists look at work as a trade-off. You really want to just be laying around all day, but if you want stuff, you've got to work. And so, people work to get stuff and that's why they work. And, if they didn't have to--if they could get stuff a different way--they wouldn't work. We talk about incentives or welfare programs, we talk about tax incentives that discourage work--economists do--and Universal Basic Income would be an even more dramatic change, if it happened. But, there's a voice inside me and a voice, I think, inside other--a lot of non-economists especially--that says, 'Work is where we get our sense of meaning.' And, some people would say, 'No, no, no, no. I hate my job. I do it begrudgingly.' You don't. You love your job. Not every day, not every minute, but you do love your job. I love my job. I don't have any envy of you. I have a little bit because--there's nothing poetic in me. I'm a bit of a, not as much a Wordsworth [William Wordsworth--Econlib Ed.] fan, but the poet's desire for that romance of land. And, I think--one of the things that comes through very strongly in your book is: Work is what we came here for. When I was reading your book, I was reminded by the Gerard Manley Hopkins poem, "As Kingfishers Catch Fire". And, it's the last line of the first verse--it's the last part of the line: ... What I do is me: for that I came. What I do. My work, my activity. It's not an intellectual thing. It's not a contemplative thing. That's not me. What I am is what I do. And, that's why I'm here. 'For that I came.' That screams out in your book. So, talk about how your father and grandfather's work ethic, what it was and how it affected you. James Rebanks: So, that's a good question. I'll come back to my family in a second, but what I really think when I hear you talk is, work was ruined by the Industrial Revolution. Work was ruined by economists. The Industrial Revolution thinks it's great to break apart work--doesn't it--into highly, highly specialized, simple tasks that anybody can do if you put them in a row in a factory. It doesn't ask, 'Is that work more meaningful to the people that do it?' afterwards. And, I'm not an absolute fool, out of the space of light[?]--making a pencil in that way is infinitely more efficient than doing it with one person trying to do it all with all the wrong skills. I know that. But, the idea that we're--and I find this all the time, particularly with very educated people, the idea that we should be--that people are trying to escape from physical work, I think this is just nonsensical. This has no meaning at all in my community. I'm terrified by technologies that will take away people's work. Because, what I hear in that is: we'll take away their sense of purpose, we'll take away their sense of meaning. We'll leave them bitter and angry and ripe for being exploited by populists and other sort of political lunatics. I would put an ax in the machine right now, quite frankly, with some of the AI [artificial intelligence] and some of the technologies that are out there. And, I don't care how badly I'm judged for that. But, in our family, it wasn't that work itself was elevated, it was that the life that we were part of was all you could hope for, in a way. And, it had ups and downs, but to participate in it gave your life meaning. And, maybe that doesn't make sense to other people, but--so, my grandfather's life was the sum total of all the work that he'd done. The sum total of all the seasons that he'd been through, the sheep sales that he'd gone to. And, I think my father was even worse. My father was a hopeless businessman. So, when I'm 20 years old and I'm starting to read books about economics and I'm starting to wonder what's wrong with our world and be more economically literate, my dad's going to help the neighbors and not charging them any money for leading the haying and things. And, I'm like, 'Whoa, why are you doing that? Why are you working for nothing? This makes no sense.' But, for him, the money didn't matter because at the end of the day, you'd earned the respect of your neighbor and that made you closer together and the neighbor would come back and help us at some unspecified date in the future future. And, we were all better off because the work got done anyway. The hay had to go in the barn and the livestock would be fed. So, my dad saw--I think my dad saw the world as just a lot of important work that needed to get done. And, a meaningful human life was to be one of the team of people getting it done. Just, that was it. And, yeah. I know you mentioned in the introduction that they have really, really strong ethics about that. To stand and watch somebody else work or even to have a servant that would work while you did nothing, was completely against the ethics of my family. We would've all felt deeply, deeply uneasy. Nothing in our background prepared us for that. Everybody--when there was a job to do, everybody jumped up, not only to do it, but to be seen to be doing it because we didn't think we were--there's a strong sense of egalitarian in us, really. The idea that somebody else's job was to run around and do things for you, that would've made us deeply uncomfortable. Although you could argue my grandmother was doing that for my grandfather, but there's a whole other debate that we have there. Yeah. |

| 35:06 | Russ Roberts: I just want to say one thing in defense of economists. I don't think we're responsible for the Industrial Revolution. What we're good at--and I think this is important to add--is understanding the full picture of what sprang from that. The division of labor creates wealth. I think Smith is absolutely correct about that. You're free to ignore it. You're free to be a jack-of-all trades, as your family is. But, if you don't ignore it and participate in that weird social milieu of specialization, you create something extraordinary, which is a higher standard of living. And that allows things like a longer life expectancy, medical innovation, and so on. So, the complexity of it is that ChatGPT, which I'm uneasy about as well--we've done a bunch of episodes on it, we'll do more--is going to create other amazing things that will not be seen directly as its consequence. And, I think that's also true of some of the innovation implicit in the Industrial Revolution or the Agricultural Revolution that transformed America and Britain. In America I know the number is better, but I guess they're pretty similar. In America, in 1900, 40% of the people worked on the farm and today it's 2%. And, I know you wrote it's 2% in England today. I don't know what it was at 1900, but it was more. And there's something glorious about that, because all these other things could be created because we had to devote fewer resources than we did before to farming. But we lost something. And I think, as a free market economist, I'm coming late in life to the idea that we lost something. And I think that's important, too. And, I'm not--unlike you, I wouldn't put an ax to technology, but I do think we as human beings should be aware of what makes our hearts sing. And, it's many, many things. It's work. It's a sense of belonging, it's a sense of transcendence, it's a sense of family in many situations. It might be a worship of the Divine. There are many parts of our essence that need those things to feel alive and to have a life of purpose and meaning. And, we've lost some of that over the last hundred years, maybe a lot of it. And, we see some dysfunctionality, I think, around the world, even in places that have lots of resources but don't seem so happy. So, I think these are all complicated. James Rebanks: They are complicated. And I know, actually, if I'm being honest, I don't really disagree with you about the good that came from lots of those changes, as painful as it was. I'm not some crazy person that wants to roll back 200 years of economic progress. I don't want to do that. But, what I would say, if we're going to give economists some grilling--and I don't get many opportunities. Let's do this. What I do think--I remember reading a thing about the Amish, okay? I remember reading, when a new technology comes to an Amish community--they all work differently, because I understand they work on a sort of parish or county basis--but in some of the communities that I've read about, they have a discussion. There's actually a conscious discussion about the impacts of this technology on their world. And, they judge the technology and whether they should adopt it in their community in a thoughtful way. Now, I don't know whether they get it right all the time, and I'm not pretending that they do. But for example, if they have a new farm implement, but it would replace the work of six of the men in the village and six of the men in the village have six families living from this work, they're weighing up the good and the bad of this thing. And, I just think we don't do that. I just think there's far too little of that, where we stop and we say, 'Okay, what is the real impact of this change in agricultural technology or this change in artificial intelligence technology?' And, there's no off ramp when we're jumpy. There's no stop. There's something about the way that we think about economics, which is--I think it's based on a Whig version of history, what the English call the Whig version of history--which is: things will get better and better and better in an eternal process of progress. And, I think we're stuck in that really, whereby when you try to say to people, 'Whoa, stop, this could be disastrous,' nobody wants to stop. Nobody wants there to be any limit on technology. Nobody wants us to say no to anything. And, I just think we're old enough and wise enough to have some of those conversations. And, if it results in some Nos--not all Nos--but if it results in some Nos, I think we'd avoid some disasters. I really do. And, certainly there's nothing in the economist that I've read so far--which is limited--that is about that. That is about there might be legitimate Nos, there might be legitimate choices to turn away from some things because maybe we don't want those millions of people to be mad bad with meaningless lives that feel angry because they're replaced by some technology that probably is only going to benefit half a dozen billionaires, anyway. Let's be honest. There's deep, deep, deep, deep inequalities of power and wealth have resulted from the things that we've done. It isn't about all of us, is it? It's not. Russ Roberts: No, I disagree with that, but that's the least of, I think, what we're talking about. I think a lot of people benefit, but I'm not sure we really want it. I mean, this device--I'm holding up an iPhone on the YouTube version of this conversation--the smartphone is, it's like my favorite thing. I'd like to say after my wife and children. But, my behavior doesn't always suggest that's what I actually think, because I pay a lot of attention to it. And, I'm very grateful that my children were raised mostly in an era before the smartphone was ubiquitous. And, probably the only disagreement we have over this is who should have the privilege of saying No. So, I think it's very important that all of us as individuals--and maybe as communities in certain settings like the Amish--can decide to limit or restrict or avoid certain types of technologies and say to the rest of the world, 'Go ahead.' I mean, if people want to use their smartphones 24/7, and many people do, go ahead. If you want to have a technological Sabbath, that's up to you, where for 24 hours you don't use any screens. If you want to merely put your phone away at dinner or meals with friends, that's okay. I mean, there's a whole range of things we should do. But, I would rather--as a classical liberal, I would rather preach to the individual and the family and not want the government to decide because they tend to listen to the billionaires more than listen to me. James Rebanks: I'm going to kick back. So, why are we talking about this? I know you haven't read my second book yet, but my second book, English Pastoral, is-- Russ Roberts: I read a good chunk of it this afternoon, James-- James Rebanks: Oh, good. And, it addresses this. And it basically explains what happened to farming after the Second World War in particular. And, what happens to farming after the Second World War is that we believe in progressive change. We believe that all technologies are good. We believe that--or actually whether we believe it or not, technology changing our systems sweeps all before it, whether we like that or not. And, it makes food very cheap because exactly what the economist says it will do, and it makes people's standard of living higher, undoubtedly. But, what it doesn't do at any point, what it doesn't do is to ask difficult questions about what the ecological consequences of those changes will be. Nowhere. Russ Roberts: Fair enough. James Rebanks: So, to break it down to really simple stuff, somebody in the John Deere factory in Chicago decides to build ever more efficient combines. How could efficiency be wrong on a combine? It sounds great. But, what happens over from maybe 1950 through to 2010, is we have combines that don't drop any grain, right? When we had inefficient combines that dropped lots of grain, through the winter, millions--billions around the world--of birds and insects feed on the grain that's wasted from the inefficient combine. And, somebody very clever, who is an engineer--who only has one job because it's a simplified job in a factory as a designer--works out how to not drop the grain. Now the ecological consequences of that--nevermind pesticides, nevermind all the other 20, 30 things--are absolutely disastrous. So, we're doing things in silos, but when you apply them to the real world in a sort of free-market/everything's-progressed kind of way, you[?] trash the world. And, I've got to confess, because I'm talking to you: In my mid-twenties I became very cynical and world-weary. I thought my people were out of date and I believed in mere liberal economics. I was enchanted by people that now horrify me: Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek and Gary Becker and all the rest of that. I read all their books-- Russ Roberts: My heroes, James-- James Rebanks: And, they explained the world very, very well, actually. Just like Marxism explains revolutions very well in industrial societies. It was really good. I read them and I was, like, 'Okay, this is how the world works and we're on the wrong side of history. We're losing.' And then, I went back to the farm and I looked at everything. I'm like, 'It's not getting better. It's getting worse. Worse for people, worse for nature.' At the very least, there's some blindness in the theory. And, I would argue the theory is just way too simple. It works well for pencils, it doesn't work well for fields of grain. And, I think where I'm at in my mind is that there needs to be some separation. There are some things that clearly this is a beneficial progress for. Maybe when you're making iPhones, it doesn't matter. You can do it in the most free market way imaginable. When you get to a field and it's literally nature's winning or losing, depending on your technologies, depending on your trade policies, I just don't think it's going to end well unless we step out of that idea or at least develop it a lot so that we start to think about making good practices pay. And, I know technically that there are really interesting ideas about how people should just pay more through a market mechanism for things produced in the right way. I'm not completely stupid about that. Maybe. But we're just getting everything wrong at the moment when it comes to farming and the environment. So, from somewhere we have to have a new paradigm of thinking about the economics of it. Russ Roberts: It's going to be challenging. But, I'd like to have that conversation over a drink in the Lake District, in your barn if we could, if you'll have me. |

| 46:28 | Russ Roberts: But, I want to move on to a different topic, which I'm deeply interested in now that I live in the Middle East. In the Middle East, there's a lot of negotiation. When you're an American, there's a little place--there's room in a couple places for negotiating things. But, most of the time there's a fixed price; you pay it--often a good price, it's fine--and you're free to not pay it if you don't want to. But, here in the Middle East, a lot more things are up for grabs. And, in your life you write really incredibly about negotiating with the neighbor, going to her kitchen. I think you sat there for three or four hours over tea. Talk about what it's like to buy in that setting. Talk about what you were negotiating over. And, it's somebody that you're going to see again. It's not just somebody--you pop in to buy a house and you got to haggle over the price; or you're buying a new car. This is a repeat encounter you're going to have with this neighbor, and you want her respect, but you also don't want to be taken advantage of. And, she probably feels the same way. Talk about that experience. James Rebanks: Okay, so the first thing in our world is that no one's going anywhere. Not only are you going to have to live with the person you're doing business with for the rest of your life, seeing them on a weekly basis, but in all likelihood, your children and grandchildren will deal with their children and grandchildren. That changes the nature of this. So, a lot of modern business, as you say, is anonymous with somebody else. You get the best price, you get out of there, you're never going to bump into them at the cricket club or whatever, the golf club. But, I was brought up with a very strong ethics of how you do business. And, I write in the book about my grandfather going to do business with another sheep farmer. And, my grandfather worked out a way of making money. And, it was that the news about sheep prices got to the mountain valleys slowly, and he worked out that he had a motorcar and he could get into those valleys faster than the news, and he could buy sheep with market information a little bit better than other people. And, he could bring those lambs, walk those lambs out with his men, make a good price at the market. Now he sounds like a modern businessman there. He's sort of cheating by using insider information. But, there were rules to this. You weren't supposed to screw these people because you couldn't go back next year. You don't want to be thought of as a crook. So, one year he bought some sheep way too cheap. And he got back--got home from this journey--and the price had gone up even further. And, he knew it looked bad. He bought these sheep way too cheap. So, he drives all the way back to this remote valley to see the farmer with some money and says, 'Look, I pushed you too hard on this deal. I need to give you some money back.' But, there's another counter set of ethics, which is once you shake on a deal, it's done. So, the other farmer says, 'I appreciate you coming, but I shook on the deal. That's my problem.' So, my grandfather has to work out how to get out of this moral hole he's in where he's screwed the guy and the guy won't have the money back. And, the only way you can come up with is the following year he deliberately goes and pays more than he should for the sheep to make up the difference. So, that's what this world is at its best. And, there's another thing on the mountains here where a lot of our sheep flocks live together on the common land, on the mountains, and then we bring them down together. Sometimes lambs are born up there and you can't tell who they belong to. And, it's, you have to pee[?] in the pens, work out who the mother is and piece it together. But, if we're not sure--so there's an unidentified sheep--the farmers, rather than claiming it, which would be their economic advantage, we'll all push to not claim the sheep because nobody wants to be seen as a profit seeker over the community. So, that's just the way I was brought up. So, when I go to buy a flock of sheep on the mountain, and these sheep always have to stay on the mountain because of the pattern[?], the woman who is selling them to me is: a). she spent 10 years checking me out. Am I a fit person to take on her pride and joy and keep this tradition going? And, she's just about decided that I'm not an idiot after 10 years, and then I have to buy them off her. And, it's a game of respect. That's why it takes three hours. She's asking me for a lot of money. And, I'm finding rhetorical ways to make her feel very valued and respected by bringing the price down to something that I think is fairer. And, yeah, we haggle on and on and on. And, ultimately, I do buy the flock of sheep off her. And, now she's absolutely furious with me because I've had a lot of prize-winning sheep from what were once her flock of sheep. And, I've done slightly too well with them. So, she's irritated with me. But, that's another story. But, the thing here is, what everybody's trying to do in my community--and I'm slightly over-theorizing it--but what they're trying to do is to have a community where you can not feel ashamed, not feel greedy, not have the wrong reputation, and can live alongside each other even though you're trading with each other. So, it's: Yes, make a profit, but not exploit unfairly the other person. It's sort of trying to strike a balance between the two. And, some of that's just enlightened self-interest. When you go back next year, if they think you're a crook because you bought them too cheap, you're not buying them. The other guy is. So, some of it's sort of enlightened self-interest. And, I'll give you another example. There was a sheep farmer on the Pennines, not far from here, a few years ago. Stole sheep on a common, which is a heinous, heinous thing to do because the whole system is based on trust. And, he was caught. He went to jail actually for doing this. And, when his sheep went through the sell yard--the auction mart--all of the farmers turned their back on the sheep being sold as the ultimate disgrace: 'We won't even touch your sheep because we disrespect you so much.' And, one farmer from another district didn't know what was happening and bought these sheep. He goes into the auction, the sale yard office, and says to the auctioneer, 'What just happened? What did I just step into?' And, they explained it to him and he said, 'Oh, in that case, I don't want to buy them either,' and hands them back. So, it's a slightly Old Testament. It's a little bit brutal, but I see a lot of good in that, really. I see a lot of people who are trying hard not to screw each other. Russ Roberts: Yeah, no: it's beautiful. Economists could write about the power of repeated dealings and restraining exploitation. That's part of it. But of course, it's more than that. It's something being created there, a sense of community. And of course, that sense of community is relied on in crises and in other times for people to work together. James Rebanks: And, I'll just check another one: and, we don't all get on great. There's rivalries and feuds and all sorts of things. There's some farmers not a million miles away from where I'm sitting now--I have very different ideas about things to them. Okay? We don't really like each other. We're never going to be best friends. And, yet, when my father died, they were the first people to come, and they said, 'If we could do any work on the farm this week, let us know.' One of the wives cooked a cake for my wife and brought it. You're like, 'Whoa, we don't like each other, but you are actually going to look out for me in my worst week.' And, I just remember thinking, 'Wow, that's something.' Russ Roberts: Yeah. Russ Roberts: No, it's beautiful. James Rebanks: And, sorry, can I go back a couple of steps? Russ Roberts: Sure. James Rebanks: So, when we're talking about work, if I'm really honest with you, I don't think there's anything more important for a human to do. If I'm honest, then some kind of contribution to building a better world around them with their partner, with their family, with their community, with their country--so, to me works the opposite of meaningless. It's the absolute meaning. Let's build better communities. Let's restore our environment. Let's grow food that's healthy for us. I want to do more of that, not less. I'm now looking at: How can I help people who maybe haven't got land, 'Come onto my farm,' and we'll have some sort of cooperative that grows, maybe fruit and veg through the summer or something. I want more cooperation, more collaboration than even we do at the moment. I feel like that's how we're going to mend the world, the mess that we've got into. |

| 55:04 | Russ Roberts: It's a nice idea. Before I forget, I want you to say something--describe the process--because I love this. When a lamb is born and its mother dies in delivering the lamb, or the lamb dies and the mother is bereft of offspring there, tell what you do with the skin, because that's an incredible story. James Rebanks: So, if anybody's listening to this while they're eating food, maybe turn away for a second. But, basically there's an ancient thing that's been done for forever, really, in shepherding communities, which is the mother accepts the lamb as hers because of the smell of the fleece--the lamb's fleece. So, if a lamb is dead and we're trying to adopt another one on, pretty crude--it's not the prettiest thing--but we cut and pull off the skin of the lamb and we make it into a waistcoat; and we cut holes and put the legs of the lamb that's to be adopted on through that waistcoat of the old lambskin, and we put it with the mother. And, instead of having a rejection and the lamb not having a mother and it being a mess, and there being an orphan lamb and they have a bad survival rate, often their mother will have the lamb straight away just because she smells the fleece of her own lamb and she's like, 'Okay, that's fine. You can drink my milk.' And, 24 hours later, 48 hours later, we'll take that skin off. That's the end of the grossness. And, then the lamb will be passing her milk and will smell like her anyway. So, yeah, there's a lot of things about our world wouldn't be for the faint-hearted, but they're things that have always been done and things that work. The test of these things is, does it work? Does it make these things function better in a way that works better for the animals and everything? Yes, it does. Is it a little bit gross for an hour or two? Yes. Russ Roberts: Do you eat lamb? James Rebanks: Yes. Love lamb. Russ Roberts: And, the farm itself is producing--when you sell your sheep, where is the revenue coming from? James Rebanks: So, a lot of the really big farms will only produce commercial sheep. So, they're producing two things. They're producing breeding sheep for other farms. So, a mountain farm typically breeds young females to sell to lowland farms, so you're not using the grade-one agricultural land for the breeding of the replacement females. You do it on the poor land in the mountains and sell them down. And, then the males are being used for meat. But, even there, they often live on two or three different farms. So, they might start on the high mountains in their first few months, and then the first winter they might go to a lowland farm and they might actually be finished and fattened on a third farm as you're exploiting the grass in different places by moving them around the districts. So, there's an ongoing--in all of our communities there's like auction marts[?] where this trading is happening all the time. I need to get lambs off in the autumn before the winter, off my land, because I'll be overstocked. The farmer 20 miles down the hill on the coastal plane, has lots of grass going into winter. He says, 'I'll have those,' and they move on. And so, yeah, we have this sort of ancient trading relationships, some of which are taking the sheep in the same place that we used to take them with transhumance walking them in the winter. It's amazing. It's basically transhumance with a couple of economic exchanges in the middle. Yeah. Russ Roberts: Explain. What do you mean? James Rebanks: So, transhumance is when you walk with the sheep from the high mountain in top in summer. You walk them down to the lowland coastal plane where the grass is in winter. Now this land all got settled and fenced and parceled over the last thousand years so that you can no longer walk them. But, what we would do is we would sell to the farmer who's down there who has the grass. So, they would come to the little auction marts--these little round buildings where the sheep come through, maybe 50 or a hundred at a time. And, those farmers will queue up and buy those mountain lambs and take them down there. Now, historically, if you go back 2000 years, the same sheep of the same mountain might be going to the same place to eat the winter grass, but now it's done through a trade. Russ Roberts: And, what about the wool? James Rebanks: So, the wool is increasingly worthless, which is another insanity of the modern world. So, we're all wearing plastic clothing, which is very convenient. There's all sorts of clever things, but every time you put it in your washer, it's putting millions of microplastic modules down the drain and into your river, into your sea. We should be wearing more natural synthetic--sorry, non-synthetic natural fibers. Wool would be a brilliant one. Unfortunately wool is almost worthless. We have a niche use for our wool, which, we make it into tweed. Got a friend called Maria, and on social media she's at-Dodgson_Wood, and she's this amazing entrepreneurial farm woman. She makes different tweeds for different valleys. She sort of tells you the full provenance of the wool--which farm it came off, what kind of sheep it came off--and that really, really beautiful tweed: rugs and throws and bags. So, I'm very lucky. She does the value adding for me and pays me a share of that. Russ Roberts: But, if I'm getting--you're a specialist in a particular kind of sheep herd. What are they? James Rebanks: Yeah. So, there's the selling of the breeding sheep, there's the selling of the commercial sheep, there's the selling of the wool; but there's also a hierarchy in all of the breeds of sheep. And, if you have a flock of sheep at your house, let's say you have a thousand sheep, you need 20 rams each autumn. Now you don't want any 20 rams. You want to improve your sheep. You might want more wool, you might want more meat. You might want a certain aesthetic style of these sheep because that often matters in the breeds. You've got a thousand sheep. You don't have time to do that breeding program to breed the better genetic rams. So, I do that for you. So, we specialize in breeding the rams, which we call Tops. That's our dialect word for them. And, we're basically doing a smaller flock, but a very, very controlled, very thought-through sort of genetically--how am I putting it? There's sort of elite genetics which have high value. Yeah. So, you would come to me and buy 20 rams, and because you're an economist, I'd charge you 1200 pounds per ram. I charge everyone else a thousand. Russ Roberts: I'll just alert listeners--it's a very appropriate episode to come after the interview with Les Snead, who is the general manager of the Los Angeles Rams. That's a really bad joke. So, I'm fascinated by the wool thing. I mean, I love wool, personally. I love wool sweaters. I love a wool undershirt, which is a magnificent fashion accessory in travel. That wool must be coming from Australia, New Zealand? It's not coming from you. James Rebanks: So, the actual wool of my sheep--because they are very specific mountain sheep from this wet, cold place--is quite coarse. It's good for all the garments and tweeds and sort of rough stuff that you wouldn't have on the skin, you'd have it over the top. But, yeah, there's masses of sheep in South America. There's a lot of sheep in China, a lot in New Zealand, a lot in Australia. And, some of those places, including Southern England, specialize in much softer wools, which would be for things that would go closer to your skin. Undergarments and vests and things. I think Edmond Hilary went to the top of Everest, and Sherpa Tenzing, wearing nothing else but New Zealand wool. I shouldn't be plugging New Zealand wool, but wool itself is an amazing--there's all kinds of wool--it's an amazing product. And, that's the way we got to go. Again, I don't mean that everyone should be wearing wooly jumpers for everything. It's got to be a little bit more intelligent than that. But, we definitely need to be using more natural fibers, because there's no shortcuts. Russ Roberts: There's no what? James Rebanks: There's no shortcuts. We're told that plastic, synthetic clothes are just fine. They're convenient. They make your life better--all those 1950s adverts. But of course, they're not better than wool that the proceeded them in lots of other ways. There's real drawbacks. And I'm sure you care as much as I do that the real cost of things, the externalities are reflected in the market price. Otherwise, we're in a real mess. Russ Roberts: James, those Oxford years paid off. James Rebanks: You hate having me on this show. Russ Roberts: What? James Rebanks: Are you hating me right now? Russ Roberts: No, no. I'm enjoying it immensely. I learned so much from your book and the writing about what it's like to work close to the land. I mean, I've spent some time in my life against the romanticization of farming. You don't romanticize. Well, the reason I like your book is you don't romanticize it. But, the good parts, you're very eloquent. |

| 1:04:03 | Russ Roberts: I want to close with--let's talk a little bit about the Lake District. We've had a number of episodes on this program about the phenomenon of re-wilding. And, of course, many people assume that the Lake District is so iconic. It's so British. What could be more natural? But of course, it is formed by the centuries and millennia of sheep farmers who have made it what it is. And, if we went back 2000 years, it wouldn't look anything like its current idyllic patterns that Wordsworth and others were so taken by--in particular in contrast to the urban life that they were living. How do you feel about that? Obviously, the reintroduction of various species that were native to your part of the woods--there'd be some woods, be more woods--and those native species, a lot of them would eat sheep and would make your life less pleasant. But, I know you're also involved in wider global issues of farming and wilderness. And, what do you feel about this rewilding movement? James Rebanks: So, honestly, I'm conflicted by it. If it means humans are responsible for the world's ecosystems now, and we have to put way more nature in them, I'm on board. In fact, I'm a cheerleader. I'm up for this. Tell me all the ways I can do it. In fact, I've planted--with friends--36,000 trees. We've done 25 ponds. We've restored pastures. I'm massively into putting more nature into the world. No fight from me at all. I'm a cheerleader for it. But, there's another side to this, really, which is--and the complicated bit of this is basically what's called land-sparing theory, which I think is an Edward Wilson idea. I forget where it comes from. But, basically, if we embrace every new food technology or every new agricultural technology, can we produce all the food we need on a smaller and smaller and smaller--maybe minuscule--area, if we did everything we could to make the rest of the world wild? Now that sounds great, I reckon, if you're an ecologist and all you're trying to think about is how you get more nature. In the real world, it's really problematic. And, it could really quickly become pretty nasty politically. So, some questions immediately spring to mind which is, 'Okay, but most of the land belongs to people. How are you going to get hold of it? They don't want to leave it. They love it there. Are you going to displace people? Or, if you're not going to displace them, how are you going to persuade them to live in a fundamentally different kind of landscape?' And, we don't have levers for top-down pushing. I know people like Bill Gates and others would probably like that, but we don't have that. We actually have a world in which land is in many, many, many hands. And, actually what we have to do is persuade people to do progressive things on their land. But, a lot of the wilder--no pun intended--a lot of the wilder fantasies about rewilding are problematic. They're--not least, it assumes that all farming is bad for nature. Now, that's just not true. Like row cropping, sort of in the Midwest style, is pretty dreadful for nature and often dreadful for soil. A lot of the extensive cattle grazing that we do increasingly on our conservation grazing is really good for nature. It's often mimicking something that existed 5,000 years ago, almost better than what would be there now, because some of those species have vanished because of extinctions and other things. And then, there's an American lady called Emma Marris, who wrote a really good book called Wild Souls, about the ethics of reintroducing animals. When you start to think about wolves, if you're a wolf, do you want to live in modern Britain where there's almost no wilderness? where you can't walk for 15 minutes without being hit on a road? where most of the food is domestic farm animals? where there's a guy or a woman with a gun or pets that people are going to be really unhappy about their pets--dogs--getting killed by wolves, or you're just going to be in the wrong place all the time, or mating with domestic dogs? It's just way more complicated than: Let's make the world wilder. It's full of real issues. And, I think they need to be really carefully navigated. And, I actually think at times it becomes quite arrogant: 'We want this land to be something else,' and the 'we' is often very urban and very middle class and quite elite. And, I think what it really needs to be is a conversation with the people that live in the different landscapes that we want to change about what they want, what they're doing now, what kind of support they would need to change the landscape, persuading them that we need more trees or more scrub or beavers reintroduced. And, I'm very up for having those conversations. I'm very up for being a grown up in the room that says, 'Okay, how do we adapt to that? How do we change?' But, it's not all easy. When you know about farming, when you know about landscapes, it just isn't easy. So, it's got to be negotiated and it's got to be consensual. And, some of the rewilding stuff is just cheap shots thrown from high heights. Russ Roberts: Well, I want to encourage listeners to listen to the episode we did with Isabella Tree, and with Pete Geddes on the American Prairie Reserve. It's a fascinating issue. I think what your book and our conversation highlights is that the environment that you live in, you've changed it. Your family has changed it, your ancestors have changed it; but they live there now. So, to treat it as the home of the wolves or the lions or the cougars--it should be more complicated. James Rebanks: And also, it's worth saying: in North America and many other places in the world, they have genuine wilderness areas, places like Yellowstone. Russ Roberts: Yeah. James Rebanks: Now, there's often a problematic history to that about displacement of the other people who are there first, but they are effectively state owned. They are effectively wildernesses. And, people get very confused by British national parks because they're farmed, they're lived in, they're hectic, and it's because it was a completely different deal. They're basically what UNESCO [United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization] would call cultural landscapes, which is: people have shaped them in endless ways till they're basically like gardens. They're not like wilderness. And, the deal of them not becoming national parks was kind of a post-war thing where British government said, 'We're not going to buy them. We're not going to take control of them. You keep the ownership of them; you keep farming. But, we want to bring a whole lot of people who we think deserve bank holidays, deserve paid holiday, need somewhere to walk, need somewhere to feel fresh air, or sail on a lake.' That's what the deal was. So that, too, is complicated because it doesn't belong to the state. It isn't primarily for wilderness. Russ Roberts: Yeah. James Rebanks: There's undoubtedly a need for wilderness in every country, in every ecosystem. But, that isn't our starting point. So, yeah, and I have to say: We do so much stuff about habitat restoration. But, by some definitions--I mean, I get accused by farmers of being a rewilder because I've done so much nature restoration. And then other people say I'm a critic of rewilding. I'm like, 'No, it's just too simple. It's just jargon.' And, I'm not criticizing Isabella Tree there, because I know Isabella. She's great. And, I've been to their place. It's amazing what they've done. We definitely need pockets of that. But, I actually think--something like 75% of modern Britain is farmed. I think the big game isn't actually those pockets are perfect. It's the 75% that's farmed, making it substantially better. And, that's where my head is. That's where my second book, English Pastoral, is. It's about, 'Okay, what would that look like? How would you persuade people to do it? What sort of habitats would they create? How would you justify that economically? What sort of risk?' And, what we have--sorry, I'll do this very quickly--but what we have in Britain at the moment is a lot of talk about nature restoration, a lot of talk about rewilding; but actually a lot of deregulation of farm products and our relationship with supermarkets. Free trade deals with the rest of the world, so things are coming in and undercutting us from systems that don't have the same regulation. So, the farmers are quite rightly turning around, going, 'Hang on a minute, you people are hypocrites. You want nature, but you pay for monocultures.' So, I'm not the font of all wisdom on this, but I think we need to think about this in its totality. We need to think about its impact on people and what we really want to pay for. Because, it's very easy to say 'Wilderness,' if you don't then pay for it, if you don't pass the laws, if you don't have the trade policies to back it up. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been James Rebanks. His book is The Shepherd's Life. His second book is called English Pastoral. It's also, I think, been issued under the title Pastoral Song, right? Is that right? James Rebanks: Yeah. In America it's called Pastoral Song. Yeah. Russ Roberts: James, thanks for being part of EconTalk. James Rebanks: Thank you. |

James Rebanks's family has raised sheep in the same small English village for at least four centuries. There are records of people with his same last name going back a few hundred more. Even his sheep are rooted in place: their DNA is from Viking times. It's enough to make anyone feel insignificant--and according to Rebanks, that's a wonderful thing. Listen as the author of The Shepherd's Life speaks with EconTalk's Russ Roberts about the deep pleasures and humbling privilege of being a sheep farmer.

James Rebanks's family has raised sheep in the same small English village for at least four centuries. There are records of people with his same last name going back a few hundred more. Even his sheep are rooted in place: their DNA is from Viking times. It's enough to make anyone feel insignificant--and according to Rebanks, that's a wonderful thing. Listen as the author of The Shepherd's Life speaks with EconTalk's Russ Roberts about the deep pleasures and humbling privilege of being a sheep farmer.

READER COMMENTS

Shalom Freedman

Jul 3 2023 at 10:17am

This was a truly fascinating conversation. Russ Roberts reveals a richness of economic and life understanding in a world, and with a remarkably interesting and uncommonly wise person, the shepherd and author James Rebanks. They speak about family tradition, the meaning of life in community, the value and meaning of work, the practice and economics of sheep-farming, the situation of farming in today’s world, the question of re-wilding and much else. There is much I never heard or thought of in this conversation and I believe most listeners will also learn a great deal from it.

Gregory McIsaac

Jul 5 2023 at 12:46am

When James Rebanks was asked about the US writer Wendell Berry, he responded as follows:

“I was just finishing my first book when I read Wendell Berry for the first time. He isn’t well known in the U.K. outside of food and farming literary circles, or wasn’t until the last five years or so. It was somewhat humbling to realise that someone had come to very similar conclusions to those I was reaching, but had reached and articulated those conclusions fifty or sixty years ago when it was far less clear what was happening. I have visited Wendell’s home and his community, and done an event together in Louisville Public Library. I respect him greatly and he has been a friend and champion of my work. And I’ve been able to repay that a little by my U.K. editor publishing his essays and his poetry.

“Pastoral Song owes more of a debt to Wendell, and to other American rebel heroes of mine, like Rachel Carson and Jane Jacobs. It felt absurd that he interviewed me when we were on stage together, as he is the boss on this stuff, and I am a mere upstart. He made me laugh because he told me that he had about nine copies of my first book because his friends kept sending it to him saying “you will love this.” I can only doff my cap respectfully to him as the great agrarian radical that he is, and perhaps, as a younger writer with similar beliefs, pick up the torch and carry it forward as best I can.”

James Rebanks in Conversation: Pastoral Song – Front Porch Republic

Blackthorne

Jul 5 2023 at 1:48pm

Another great episode! I enjoy the episodes where the guest is someone who is an expert on a particular occupation or product, like the one on whiskey some time ago. I appreciated that Russ didn’t push too had on points where he (and likely most of us viewers) disagreed with James. As an 1st-generation (or I guess maybe 1.5g) immigrant this episode gave me a lot to think about.

John St. Peter

Jul 5 2023 at 4:47pm

Thank you for your work! Listened last night to the James Rebeek (sp?) interview. More like this, please. Regardless, more of everything is appreciated.

P.S. Perhaps you and Mike Munger could do a show explaining the core theories/contributions of important economists that are frequently mentioned during your interviews. All too often I don’t know what people like Gary Becker stand for. Thank you.

[Comment relocated from an unrelated thread.–Econlib Ed.]

Jonathan

Jul 6 2023 at 10:39pm

Much respect to Russ for pulling back and letting the guest speak his ideas. I wouldn’t mind here Russ question a little harder on a later episode but this episode was an example of why he my favorite curious person doing interviews in podcast form.

Fredrik

Jul 8 2023 at 3:54pm

I loved this conversation with all my heart. From growing up, to nature, to work to economics and back again, with the history and all it’s people at center stage. One of the best podcasts that I’ve listened to for a long time … for econtalk that might well be since the episodes on Adam Smith. Thank you! Both of you, for your time and shared wisdom <3!

Comments are closed.