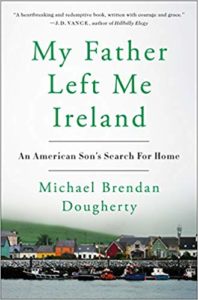

| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: May 22, 2019.] Russ Roberts: My guest is journalist and author Michael Brendan Dougherty.... His new book is My Father Left Me Ireland: An American Son's Search For Home, which is our topic for today.... Your book is an extended meditation on being a son, being a father, your Irish heritage, what it means to come from somewhere; what we think about nationalism, national identity, American culture; and a little bit more, but I think that's enough. And, despite all that it's a very short book, and I found it deeply moving. It's written in the form of a series of letters to your father. Give us a sketch of your childhood and your relationship with your father. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Sure. I was born in 1982 in the suburbs of New York, in New Jersey--in Bloomfield, New Jersey--to a single mother, my mother Mary Ellen. And she and I lived with her parents in their family home. My father and mother met while my mother was traveling through Europe; and in the late 1970s, early 1980s. You know--my mother had--her best friend was a Londoner, and this best friend was dating my father's best friend. And then my parents met, had a kind of--you know, I would say a summer love affair--that's what I've pieced together through talking to my father and going through the letters. And, then at some point my mother wrote to him and told him that she was pregnant. And my father--I think there was some uncertainty whether he would come and join in these first initial weeks, whether he would come over and have a shotgun marriage. But ultimately he decided to stay in Ireland. He went back to an old girlfriend. And, in the years afterward, he built a family with her, had three more children; and I was raised here. I got to see--unlike most American families that are broken, you know, I didn't have weekends with my father. You know, I couldn't fly to Dublin every week. Or have, like, the double holidays that most kids have. I would see my father once every two or three years. Sometimes four. Maybe a week or two, and sometimes maybe just for a few hours. And so, I knew him that way. And then, my mother, in my--my mother never married, never had any other children. And--but in my early childhood she kind of filled the home, among other things, with lots of Irish stuff. And songs. A little bit of the Irish language--she got heavily involved with an Irish language student group in the United States. And sort of attached herself to this--I don't know--have Irish-American, half-diaspora Irish culture that existed in New York and in Boston in the 1980s. And that would have, you know, had some--my mother would have been very concerned about the troubles in Northern Ireland. And would have had very strong, and typically Irish-American views on that conflict. And, you know, I can remember, I can remember people almost spitting on the name of Margaret Thatcher when I was young. That's like an early memory for me, it was that this woman we hated, somewhere. So, yeah. Those were kind of the basics of it. Russ Roberts: And, your relationship with your father begins to change when you become a father. What happened? Michael Brendan Dougherty: Yeah. So, um--I mean, it was slowly changing in my adulthood as my mother was no longer the kind of go-between or someone that he would have to deal with. You know, their relationship was kind of a wreck. And mostly because she had fallen head over heals in love with him and had his child. And he was not in love with her. Ultimately. And, um, though he admired her. Very much. And, um, so it started to change as I was a young adult, after I got out of my mother's house. But then it really started changing as I was becoming a father, in the year or two before. I suddenly had noticed, I suppose, as when my wife told me she was pregnant I suddenly I was filled up with this desire to do--it turns out exactly what my mother did, which was start learning the Irish language, start paying a lot more attention to what's happening in Ireland politically. And then also in a sense I kind of was falling in love with my father. The way that mother did. You know. But as a son. And, so the communication opened up. And this was happening at the time, you know, from 2014--you know, the books' letters, if you took someone to forensically date them, the books' letters basically run from 2014 through the beginning of 2017. And it's in this time that Ireland was commemorating some important centenary anniversaries that were important in its history. From the passage of Home Rule Bill to the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and beyond. And we're in still kind of in those centenaries now, with those, now you'd be commentating the Anglo-Irish War, and so on. So, Ireland was sort of reflecting on its own history. And I'm kind of listening in to that conversation as I am reflecting on it myself--as I'm sort of recovering it for my children. And it's a way of reaching out, understanding, my own father. So, yeah, that's kind of the heart of the book. |

| 7:49 | Russ Roberts: And along the way--by the way, my, I just was telling my son about this book and this interview, and he said, 'What's this have to EconTalk?' Which is a fair question. And the answer, one answer of course is that I'm interested in it. But the deeper answer is there are a number of larger themes because the dirty family renaissance, which is a beautiful part of the book, that renaissance that we are going to turn to turn to turn to. So, along the way of you telling that story of your own fatherhood and how it changes your own relationship to your own father, you sketch out Irish identity and Irish national story. And, in particular, you talk about that story that the Irish people tell themselves. And there's more than one-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Yeah. Russ Roberts: Some of those stories are kitchen[?]; some are romanticized. You described some of them as plastic, or commercial. Inherently false. What are some of those stories that you think should be rejected? And how would you describe the story that you've embraced? Michael Brendan Dougherty: Well, so, when you look back on--I don't know that listeners known this, but the--the focus of Irish politics from the late 19th century up until World War I is through this Irish Parliamentary Party. And for the achievement of a home rule parliament--a parliament in Dublin, the whole idea of restoring a parliament to Dublin that takes the Irish interest more seriously. And, in this period from eighteen--especially from 1898, the Queen's visit, until 1916, there's a lot of, you know, kind of nationalist culture and talk in Ireland. There is an attempt at language revival. The Irish language had been dying for a few centuries, and then really took a tremendous fall down the stairs during the famine, the middle of the 19th century. There were attempts at writing Irish history: many of them were pretty poor--just full of legendary argle-bargle about how the Irish language was the one pure language to come out of Babel. You know, something like that book made of all the most beautiful parts. And, my interpretation of what is happening in this period, when I look back on it, is it's a kind of emotional compensation for the accepted reality at that time that Ireland was fundamentally a broken nation and a kind of failure. Right? That, there's a good chance you'll have to emigrate; that Ireland is not producing anything all that important for the world-- Russ Roberts: Except for literature. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Well, that is what starts happening, in the 20th century--is Yeats and Joyce; and then suddenly this is what Ireland is probably best known for throughout the world, is it's English literature, from this period. Now, what I found exciting about the kind of revolutionary nationalist heroes of 1916 was: they decided to actually move a little bit beyond this kind of sentimental picture of the home. Not that they lacked for sentiment. They had tons of it. And they wanted to move a little bit beyond the romance, though they were very romantic. And, to try to treat Ireland in this extremely serious way, and stern way, as this great inheritance that was jeopardized and could potentially disappear from the face of the earth. There are nations that are eventually subsumed and die. And so, Patrick Pearse, Eoin McNeill, and others believed part of their project would be political and eventually cultural separation from the United Kingdom. And there was something obviously that resonated with me at that time in my life where I'm becoming a father, where you are looking back on a difficult past and then trying to build something better out of it. So, I was naturally--I had not only this primed affinity from my youth for these figures from my mother's songs and my upbringing, but also this kind of emotional time in my life, becoming a father--and you naturally, most of us naturally think back on our own childhoods when we become parents and decide what we want to give and what we want to reject. And so, suddenly I'm reading these histories and seeing, you know, men searching through the history of their broken homeland and trying to find something kind of glorious in it to build for posterity. So, of course, it really resonated with me. |

| 13:54 | Russ Roberts: But some people would react to that--and I'm sure some listeners are thinking, 'So, what's that have to do with a boy raised in suburban New Jersey? What's that have to do with the daughter of that man?' And then, I want to read a short passage where you write about your own self-image in your youth and adolescence; and I think it's a way that most of us raised in America think about ourselves, or at least many of us. Which is: We can be anything we want. We are untethered by our parents' nationality, their religion, their values. We are just blank slates, and the stylus is in our own hands; and we can write our own story. And, here's the way you describe it--rather powerfully: When I was a child the nation's president disclosed to us his preference in underwear for a laugh. The adult world that I encountered was plainly terrified of having authority over children and tried to exercise as little of it as practicable. At every turn my mother, my teachers, and the Church just sort of gave up and gave in to whatever I wanted. They seemed grateful when a child wasn't difficult. The constant message of authority figures was that I should be true to myself. I should do what I loved, and I could love whatever I liked. I was the authority. In the benighted past somewhere, there was pain and misery, but baby boomers had largely corrected this for us in their titanic generational battles. This, I would call the myth of liberation. I was raised on this mythology, and it ordered the world around me. The future ought to be bright. This was the end of history, and wasn't it good? And so my question is: You know, "In the benighted past somewhere, there was pain and misery"--so, your father comes from a country that had this terrible past where they were held down by the British, oppressed. They struggled for liberation. They rise up in 1916. Hundreds of people get killed. The leaders of this rebellion get executed by the British. Who cares? Why is that relevant for Michael Brendan Dougherty? And, particularly, why is it relevant for Michael Brendan Dougherty's daughter? Michael Brendan Dougherty: Yeah. So, um, what I try to do in the book is show how that upbringing I describe, in which there was no authority higher than the self--you know--and that this was constantly communicated to us, through--through the culture. In a hundred years we'll look back at it as a kind of propaganda. I mean, it--I almost don't even mean that pejoratively. I just mean this was what was propagated. To us. And, what I try to describe is both how, at the time that I was most under the sway of this view of the world--and in the 1990s it seemed very convincing, even to me. Um, that there was a kind of--that there was a dark edge to it. That there was, one, await[?]--it gave a weightlessness to my existence. Right? I mean, many people find, as they mature into adults they find the crucible of forming their character, is accepting or rejecting what has been given to them. And, in a perverse way, of course, I do exactly that. This book is a kind of rejection of that 1990s view of the world. But, I talk about that weightlessness. And then I also talk about, in a sense, how it left it me unprepared and ill-equipped to meet some of the real challenges of adult life. Including--even including financial disaster that my mother faced late in life. Including her death. You know, that kind of 'make you own adventure at all times'-culture actually imposes a lot on you and actually extracts a lot of costs out of you at strange times. Where, you know, like, a traditional Irish culture that still exists in the Aran Islands to a degree, there is a ritual about funeral that is kind of given to you. And, it takes all sorts of forms--prayer, ceremony, drink, what people bring to your house. When I was faced with my mother's death in my young adulthood, I was just given an endless series of menu options to begin creating a meaning out of this for myself. And that actually is a--that does impose a cost. We tend to think that it's a gift; but actually I thought it was a very mean thing to do to a bereaved young man. Which was, say, effectively, like, 'Make a meaning out of your mother's death for yourself, entirely from scratch if you like.' It's actually cruel, in its way, because it robs you of the ability to know whether you have grieved properly, or whether you've done the right thing. It leaves you second-guessing. |

| 20:07 | Russ Roberts: I want to put a Hayekian spin on it. In a way, I think--it's a beautiful example of tradition and the value of tradition. And in America today, I think we're very skeptical of that tradition. As you say, we are encouraged to think we can make our own--create our own traditions, our own rituals. And, I think what Hayek would say, although he was not a religious man and I'm sure found many traditions unappealing personally; but what he would say and I think what the pragmatist philosophers would say is that: We don't understand everything; there is a lot of wisdom in the world embodied in tradition that is not rational in the sense that, if you could pick and choose, you might not choose this particular set. And so, you were given this opportunity to just rationally make up your own. And surely that would be better? And yet, that ignores the fact that the traditions that evolved on those islands, or in my case, in Judaism--which is, you know, Jews and the Irish have some things in common-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Yeah-- Russ Roberts: language, tradition, a feeling of--at times colonialism under the hands of the British: the hands of the British in Israel and Palestine at the time. So, you know, in Judaism there's incredible, specific things that you do when someone passes away. And, of course, there are constraints. But I think what you're arguing--what I would argue, as well--is that they are actually liberating. Those constraints allow you to actually not have to think about a bunch of things. And they are constraints that weren't just imposed by some cruel person, or some arbitrary person or culture. They evolved over millennia. And "They work." Michael Brendan Dougherty: And they allow you to know that what you did was right and proper. That you did something that was worthy; and that almost becomes worthy merely because so many other people have gone this way. Right? Russ Roberts: There's an honor in it, in that way. And it's not obvious that it should be a good thing. You could argue that it--it is somewhat arbitrary. And the fact that you feel compelled to do something that your ancestors did or that your family has done for dozens or hundreds or even thousands of years--you can argue that's just some goofy habit. There's no reason or value in that-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right-- Russ Roberts: That's bizarre. Why would you think that? And, in particular, you could say--here's one way to think of the question: Michael Brendan Dougherty with the freedom to choose whatever he wants, could say, 'You know, I really like Jewish rituals around funerals. So, I'm going to sit shiva'--which means I'm going stay in my house for 7 days, mourn the person, and have people over. As opposed to, say, a Wake. A Wake, that's, 'Yeah, that's what Irish people do. But I don't have to do that.' Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. Russ Roberts: And so, you could choose your own ritual. You could say, 'The Jewish one really appeals to me.' It's fascinating to me that that isn't what most people do. They want to be part of that longer continuum. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. And--yeah, it was also part of this larger sense that this myth of liberation also not only robbed me of things like that--right?--the ability to quickly organize a funeral that would be proper and decent for my mother, but also that it seemed to somewhat dissolve people's sense of obligation to one another, even emotionally. I talk in the book a little bit about the way my mother's life, as a single mother, was not what--in a way the culture was starting to make the promise in the 1980s and 1990s that, 'Hey, single moms: you are heroes. We love you. We honor what you do.' Russ Roberts: Just a choice. Michael Brendan Dougherty: But--yeah--but ultimately, because in a sense it was her choice: She wasn't a widow. Because it was her choice in a way the fact that men weren't as interested in a single mother, you know, as a potential romantic partner or spouse; the fact that people didn't offer as much help as you would offer a widow--you know, it was because it was her choice. So, you should suffer. In a sense it was like, 'You made this choice; now suffer for it,' was the actual private and operating message from the culture. And in a way it robbed her of her sense of feeling wronged by my father, or wronged by her circumstances. And it robbed her of some of the publicly-proclaimed sense of heroism for raising a child on her own. For working hard while she did so. And so, you know--this book was also my attempt to honor her and portray her as someone like Patrick Pearse, this person who made themselves into an Irish-speaking, Irish nationalist, and then made huge sacrifices on behalf of a better future. Russ Roberts: Patrick Pearse being one of the leaders of the Easter Rebellion, Easter Rising, in 1916. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. And so, um, so yeah. I wanted to honor her that way. And so, that's right. The fact that that myth of liberation was insufficient. And it was insufficient to honor her. |

| 26:57 | Russ Roberts: I want to go back to something you said that you kind of hinted at, at the beginning of that answer, comment. Which is that, there is a certain self-centeredness to American culture, which we often celebrate. Right? Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. Russ Roberts: It's in the Declaration of Independence. To some extent. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Now, one person's pursuit of happiness is not another's. In particular, I'm not sure that the Founders by the pursuit of happiness might have meant what we, today, mean by that phrase. But, putting that to the side, I think that it's--it's almost a cliché that Americans are disconnected from one another. That we struggle to connect to other human beings. That we are lost in our screens. And some of that, of course, is pure technology. But some of it is what I think you are talking about. I haven't really thought about it. And I'm sure I'll offend some listeners who don't like this kind of thinking. But I'm going to throw it out anyway. Our obligations to each other are unpleasant, often. We'd rather they weren't there. I'd often rather not visit my friend in the hospital, take my parents' phone call with their latest computer problem, or just--whatever it is. In the middle of something. And I've tried to answer the phone, when I see it's my parents--try to answer it even it's just to say 'I can't talk right now.' Because, they are 88 and 86; and they don't get out so much. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. Russ Roberts: And so, it's an incredible kindness to take their call. And it's the least I can do, for them, given what they did for me. And I feel an obligation there. Some of it's religious--you know, there's a Biblical commandment to honor your parents. And to me, one of the ways that manifests itself in my life is I take their phone call. And, we just are--a lot of us--you know, and there are other parts of my life where I am such a saint. Don't worry. I don't mean to brag here. And you might think I'm a fool for doing that. But, I think that sense of obligation and connection to one another has been deeply damaged by our disconnect from our roots and from our religion and from our ethnic heritage--whatever it is. And it gets transformed maybe into food habits. Like, you know, Italians might eat more spaghetti than other people. Or whatever it is. But I think that's a--and of course it's a simultaneous system: as our culture becomes less connected, we're going to feel less compelled to see those obligations. So, I don't want to suggest it causationally runs in one direction. But I think part of what your book is about, and what you are saying now, is that weightless--which is deeply appealing--that weightless, tetherless way that we are sometimes raised in our culture, often emphasizes, does come at a human cost of connection. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. It comes at a cost of connection. It comes at a cost of meaning. I think. And, I think--you know, I hint very subtly in the book, I think it also comes at a cost of potentially, in our politics and in a kind of a backwash or reaction to that enemy and disconnectedness. You know--one of the things running through the book is the sense of, very quickly, a world that had been very rich for me with meaning in my early childhood, with lots of connections to a foreign country, to a large extended family, a kind of larger diaspora community--very quickly, in the space of two decades, two and a half decades, petered out to effectively nothing. It was my mother and me. And then my mother dies. I had--I was not raised with siblings. My half-siblings were 3000 miles away, and I barely knew them. And so, that--I think that that sense of the family shrinking that many of us have experienced--I think many people my age have experienced--you know, watching the reunions get smaller and not get replenished with other young people, or not be continued by young people because they scatter and move--I think there is something to that, that is, in some ways feeding the resurgent--I mean, I haven't done the studies on this, of course. But my intuition that informed this book was that this shrinkage of our social life and those connections is informing this nationalist reaction across the world. That--it's just interesting to me that--and like I said, I don't know if there's a mathematical formula here. But it is interesting to me that countries with incredibly low fertility rates often produce these nationalist movements of leaders who, you know--Hungary, Poland--they've all see their fertility rates plunge unbelievably. Now, it hasn't happened everywhere. Spain hasn't gone that way even though the numbers would suggest it. But I do wonder if there is something to it. Because I've noticed--you know, as people noticed a lot: I think that the troll-y/alt-right and other things--I kind of noticed that a lot of these young men were fatherless boys, the way I was, at one time, too. But, they were, are looking for this much more abstract connection. Maybe they don't have someone to connect to the way I did. And so I do wonder if that's informing our politics--is that, the, the feeling of the destruction of the family home is leading to this impatient, fevered, and sometimes fanatical sense of having to retrieve the glory of the larger country around it. Russ Roberts: Well, I like to say that human beings want to be part of something larger than themselves. And if it isn't country, it's religion; and if it's not country and religion, it's political ideology. I think a lot of the--something that's going on; I don't know how much of it is due to this, but something that's going on is that we're tribal. Human beings are tribal, as Sebastian Junger pointed out in his book, Tribe, that we talked about here on EconTalk. And, we'll find a tribe. And if we can't find one, we'll make one; and if we can't make one, we'll look for one and we eventually find one. And Nation as a tribe is--was in decline--it's coming back. For whatever reason. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. There's simply a generational sway, too--I think. And that's also part of the book--is that there's--people react to the previous generation. So, you know, I'm describing my own reaction to the 1990s, and maybe people a little bit younger than me are in reaction to the early 2000s, and what they see is the failures and insufficiency of the previous generation and are aiming to course-correct, maybe in a huge way. |

| 35:26 | Russ Roberts: I want to talk about something related to this, which is: You're a conservative-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. Russ Roberts: and probably the most, I'd say the most conservative idea in your book which is really out of favor--maybe 'conservative' is not the right word in this case; it might be 'old-fashioned'--is the courage and honor that comes for a willingness to die for that comes from a willingness to die for a nation, or a cause. And I would say on both ends of the, other ends of the political spectrum, two opposite ends of the political spectrum--libertarians and cosmopolitans--you can say they have something in common. But, I'm thinking of progressives who would describe themselves as citizens of the world. And libertarians, who would also describe themselves, in some sense, that way. Both groups downplay or find national borders appalling. Or destructive. Or unhelpful. And they-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right-- Russ Roberts: lay the idea of dying for your country as antiquated, or worse, foolish-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Or worse-- Russ Roberts: Stupid. Just irrational. Like, 'Why would you do something like that?' Why are they wrong? What did you find in your--I mean, you really romanticize the rebels who were part of the Easter Rising in 1916. Who, at the time, it looked liked they died for nothing. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. Russ Roberts: And whether the sacrifice is worth it today is a different question. But, talk about why you look at them the way you do. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Well, I mean it was the most counter-cultural--yeah, you'd say it's old-fashioned; I'd say it's almost counter-cultural at this point. I mean, I was raised in this--we describe this liberated 1990s. But, you would say my public school education, right, would have emphasized and juxtaposed, let's say a little film footage of the boys going over in 1917 and a little fife-and-drum of over there, "over there," and then immediately pan toward utter carnage and destruction, and the meaningless of it. And it was emphasized, in a sense like how stupid and deluded and useless and vain their deaths were. And in many case, yeah, I would say-- Russ Roberts: --you are on to something. Michael Brendan Dougherty: I would say, not that they are entirely wrong, but I would say you could criticize their commanders for spending their lives like they were nothing. But I'm now hesitant to criticize them--the soldiers--as totally deluded; and I'm actually more likely to blame the later delusion on their leaders. Um--but--the fact is--you know--now lot of little transformations happen when you have a child. But one of the ones that gets talked about, I think, very, you know, quietly or sometimes expressed among them or at least a couple of fathers, I know, which was that: You just meet your child. It's just--your baby is just born. And you suddenly feel a couple of things. One, you feel the desire to be a better version of yourself. Right? You suddenly--you feel inadequate-- Russ Roberts: Yeah-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: to the task. At least I did. Russ Roberts: You are not alone. Michael Brendan Dougherty: But, you also feel, I think--this is pretty common among men, and I don't think it's talked about often in public--you also feel suddenly and strangely, and this can even frighten you, readier [?ready you?] to kill or to die, on behalf of this child. Like, if it came to it, I would throw my life in front of a moving bus to save this child. If a bus is careening down at the stroller, it was near the stroller--of course; you'd just throw your life away. Immediately. And, that you'd be happy to do so. And, that is the basis for this larger sense of patriotism, or this larger idea of a nation as a whole, which it is in certain times. It requires you to be courageous and indomitable, valiant and proud, and willing to die, to safeguard it. Because it provides--and not just because it provides all these goods. Right? Like, I hate talking about it in this econometric way. Russ Roberts: Instrumental way. Yeah. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Overly instrumental way. But it--the fact is it does provide those goods. And so, just as you defend your child from harm and you would be willing to do violence to others to prevent the harm to your child, there are times when someone intends the harm or the death or destruction or the suborning of your nation. And, it will require some great sacrifice on your part to keep that nation alive into the future. And of course what is fascinating about the Rebels of 1916 that I'm talking about is how self-conscious they were about this--about this idea of, 'Well, even if it's a doomed battle, we have to put it up because we have to keep alive at least the tradition of rebellion.' You know, 'There hasn't been a rebellion in our generation, and if we don't rebel, then the tradition dies,' and in a sense, the nationhood dies with it. You know, they predicted it, as they were going in--you can look at their letters. Patrick Pearse and others said, 'Well, people will say hard things of us now; but we'll be blessed by unborn generations.' And he was right. And what--the astonishing thing is, is that he was right. They were at first denounced as traitors and Communists. And then as people gradually came to know who they were, they were blessed as the saviors and deliverers of the Irish Nation. Which--I have to emphasize this--was universally recognized as a kind of failed state. And so, too, their sacrifice gives it, gives Ireland the pride of nationhood back again. You know, it was countercultural for them to speak about their nation in that serious way. And it totally transformed that country. And, you know, some revisionist historians would say for the worse. They would say, you know, the costs of leaving the United Kingdom, the costs of continuing conflict in Northern Island, were too much. And you could debate that. I think, however, the loss of the Irish nation itself would have been a greater loss. |

| 43:19 | Russ Roberts: Well, you would have been even more weightless, had that happened. I think--I think 'meaning' is a tricky word. But I think you are getting at something quite deep that is very difficult for a modern person to think about. Which is: If you made a list of what you are willing to die for, I think most of us would say, 'Nothing.' Okay, maybe our children. Maybe. And I want to talk about parenting in a minute--we'll come back to that in a second. But, outside of our children, which people would say, 'Well, that's just biological. It's just evolution. Of course you'll die for your children.' But is there a cause that you would risk your life for? Most of us would struggle to answer that in America in 2019, because life is easy, for many, many people. That's a feature, not a bug, that I'm [?] have enough to think about it. Michael Brendan Dougherty: It is a feature. And it should be jealously praised as a feature that most of us don't have to do this. But there are moments of stress, and in history, where someone will be called upon to do it. And one could imagine it. One could imagine a conflict in the future where John Paul Jones's sentiment, 'Give me liberty or give me death'-- Russ Roberts: You mean Patrick Henry-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Patrick Henry-- Russ Roberts: I have to quote the first part of that, actually, because as soon as you started that I was thinking of Patrick Henry. He says, Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery. Forbid it, Almighty God. I know not what course others may take, but as for myself, give me liberty or give me death. And that's--you know, that's a heck of a speech. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. And that rhetoric, that exact rhetoric of slavery as the alternative features in the rebellion I'm talking about. And, you know, one could, one could easily imagine--maybe not so easily. But one could imagine if you were, if the United States fell into civil strife, depression, decline, and suddenly was offered the humble tutelage of Beijing's tender administration modeled on what's being done in the XinJiang Province [Northwest China--Econlib Ed.]. Suddenly, this willingness to kill and die for an idea or an ideal, and old scrap of parchment, which had heretofore been deemed a tribute to the hypocrisies of the founding generation--some of that would make sense again. It would feel urgent and necessary. Russ Roberts: And, on the flip side, it must be admitted--I'm sympathetic to your point, but on the flip side it must be admitted that the stoking of that willingness to die of course leads to militarism that is not so romantic. Not so good. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Of course. Russ Roberts: So, we want to keep it in perspective. |

| 46:32 | Russ Roberts: But, also, I can't help--as you talk, I can't help thinking of Tennyson's poem, "Ulysses." Which I can't quote entirely from memory: it's quite long so I've cheated and looked it up here. But what I was going to say before is that, if you are not willing to die for anything, you might not be willing to live for much. And I think that's a cliché, but I think there is something there. And I think that gets at the weightlessness that you felt before, before you had a daughter and before you connected back to your Irish heritage. But I want to read a couple of lines from "Ulysses," which is a romance, a romantic view, that I held when I was a child. He is talking about--Ulysses is old at this point. He has done all his great trips and Trojan War--and he says--he's about to die. He says, Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods. And then he says at the end Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. And that kind of heroism--it's not part of our country any more. For whatever reason. You know. It's just not. Michael Brendan Dougherty: We don't--right. It's not part of our education system. It's not like, people even a hundred years ago, at a boys' school, you would have athletic programs. And the athletic programs were not just about self-discipline--like, a school of self-discipline. But in a sense they were kind of a preparatory, for-potential, enlistment in armed forces. Right? They--and now we talk about our athletic programs as sort of like preparing you for the job market some day. For the strife and conflict, or whatever--the self-discipline it requires to succeed there. And we hide this idea of bravery. And honor. For, from people. And also the--you know, we teach tolerance, which is very good in a diverse society. But, you know, these martial virtues and this view of heroism also requires intolerance. Right? Intolerance of injustice. Intolerance of slavery. Intolerance of-- Russ Roberts: oppression-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Yeah. Oppression, or foreign rule, or whatever. And listen--and this is not immediately applicable in my life, as far as, you know, I have not great work of violence I can recommend to anyone to do-- Russ Roberts: Thank God-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: You know, maybe I will in the future. But people who know me, know me as pretty skeptical of war, in the modern age. But, um--but I did still feel, in writing this book, that meditating on this history, meditating on my own upbringing, that this idea of putting sacrifice at the heart of manhood was still useful to me. It was still , it still helped me make sense of my life. It still helped me make sense of what would be right or wrong to do on behalf of my children. And of my family. And also, of course, on behalf of, you know, my country, or my countries, and my Church, too. I mean, there has to be this willingness to risk, or else life becomes not just enervated but also quite boring. |

| 51:09 | Russ Roberts: Yeah--I want to--it's an important point. I want to emphasize that I don't think either of us are suggesting that violence is a good idea, or that war is a good--it's a wonderful way that people get tested and turned into something superior. It's a way people get killed. It's a horrible-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Oh, it is horrible-- Russ Roberts: a horrible, historical failure, most of the time. But I think the more important point here is passion and sacrifice: What are you passionate--but not just--saying, 'What are you willing to die for?' is over-dramatic. What are you passionate about? And, what would you sacrifice for? And I think--I want to turn to the parenting issue. You write an extraordinary indictment of our culture of parenting. You say, It's as if this language of getting ahead and technocratic manipulation becomes the default mode of thinking around us, and we adapt ourselves to it when we don't know what to say. I'm discovering now how much parenting advice and guidance is packaged this way, how it recasts fathers not only as providers but as social engineers, as "wonks." Read to your child, because children who read with their parents on average make a million dollars more over life. Eat dinner with your child, because a child who eats at a family table becomes more sociable and in the long run will marry better and get more promotions. Cuddle with a child; cuddled children get better mortgage rates as adults. As if parenthoods could be judged by the grades we got in school, or the salaries we achieved. And I think that's a real--obviously there's some exaggeration there. But I do think there is a temptation-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: is there? Russ Roberts: Yeah; there is a temptation to see our job as parents as creators of our childs' futures--which of course to some extent it is--when, in fact, I like to simply say it's part of the human experience to be with your children and to interact with them at dinner. It has nothing to do with what kind of spouse they'll become or what kind of parent they'll become or what they'll be able to do at work. It's just a glorious part of being alive and human. And, I don't want to measure it. I don't want to find out--I don't need to measure it. Michael Brendan Dougherty: There is something also kind of deeply double-minded in our culture about this, which is that, on the one hand it's like publicly the ideal, the master idea of our politics, the one permissible license for all political motivation should be egalitarian--achieving a more egalitarian world, an egalitarian society. And yet, privately, all the advice to parents is: Here's how to get the extra 0.2% advantage for your child, and how you should-- Russ Roberts: grab it-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: dedicate yourself fanatically to it. There is a kind of weird double-mindedness that way. Russ Roberts: Great point. Michael Brendan Dougherty: But I do think that there is a way--and this book weaves together the public and the private in this way, because I see it weave together in my own life. That, when in the 1990s this sense of authority over children was considered authoritarian, and I could see my mother and my school and other authorities trying to not exercise their authority over me. And now I see this idea of social engineering escaping from, or this mode of thinking escaping from Vox or any number of other political magazines, and colonizing our understanding of the family. It's a very natural thing for humans to do, is to look for a pattern in the world and then match it to everything. And so, you know, and that's part of what this book was doing, was suggesting a completely different pattern; and hopefully readers will, I don't know, be inspired to imagine some of their own from it. Russ Roberts: Well, the version of that cultural story you are telling about parenting is, my favorite version of it, the conflict with the egalitarian impulse is the column I am not going to link[?] to--I don't even want to try to find it--but I remember it vividly saying, 'It's wrong to read to your children, because it gives them a leg up. Shame on you.' Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. Russ Roberts: And, you know--I don't know where to start with that. I could probably do an hour-long monologue on how I think about that exhortation. But, I'll just say that I think that's bad advice. I'll just leave it at that. It's--anyway. |

| 56:24 | Russ Roberts: I want to talk about nationalism. I want to read a couple, I thought, beautiful passages. You say the following: And what is a nation? In this way of thinking a nation is at best a problematic, if still useful, administrative unit. That is, it's merely the arena in which technocrats and wonks do their work of making improvements to society. And now our men of letters cannot develop a political or moral thought without searching out a social science abstract from which to loot it. Most of the time, I find they don't read the studies. Why bother? The authors of the studies know what the wonks desire to say, and design studies to give their words the look of authority. It's a perpetual-motion machine. And like a machine, it generates only the illusion of a working intelligence inside it. And then later on you say the following: We are used to conceiving of the nation almost exclusively as an administrative unit. A nation is measured by its GDP, its merit is discovered in how it lands on international rankings for this or that policy deliverable. A nation may have a language, but the priority is to learn the lingua franca of global business. Our idea of doing something for the nation is reduced to something almost exclusively technical. Policy wonks are the acknowledged legislators of our world. And I think that's very insightful. You want to expand on that or say anything else? Michael Brendan Dougherty: Listen, I mean I--you know, this book is also me throwing a gauntlet down before my peers. You know, I think readers will notice language I'm borrowing and maybe bathing [?] with. And here, maybe I'm tangling with Ezra Klein. But, I saw a paper issued by John Donohue and Steven Levitt yesterday where they were looking at, I think, the 2001 paper on abortion and crime. And it had this amazing statement tucked into it, which was: 'The choice of specification in the original paper provides a strong degree of discipline on the exercise we carry out. In contrast to the typical empirical economics paper, where the researchers run many specifications and only report a few of those...'. So, the middle of this paper-- Russ Roberts: Yeah. A cheap shot. A cheap shot at our profession. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Well, not just a cheap shot, but like, if that is true and Levitt is right, that this is the standard practice, to run many specifications--basically run the data as many times as you need to, to produce a set of results buried within it that you can cherry-pick and write the thesis you were intended on writing the whole time--you know, I do worry that there is--I do sense that there is an incredible amount of intellectual fraud being perpetrated in our political discussions. A kind of--an attempt by social scientists and allied journalists to insert ideas that everyone knows but in fact when you look at the sample sizes that the facts about our social world and human behavior are based on--they are tiny. I mean, I saw this even in--I started noticing this as political commentary shifted in this direction of where you have to know social science inside and out to even begin opining. Which itself is, by the way, is I think is a kind of anti-democratic spirit. But, be that as it may: I found even papers that I agreed with or that I sensed or intuited were correct because I agreed with them--say, like George Borjas looking at wages and immigration--I would look at the actual size of the sample taken in Miami and just think: How could anyone make a judgment based on, you know, perhaps as little as 30 or 60 data points, and make a sweeping statement about mass immigration and the effect on wages? It just seemed fraudulent. Russ Roberts: Well, I recommend to all economists listening that when you are in a seminar--I may have said this before, but, when you are in a seminar and a result is presented, sometimes I just ask the presenter, 'How many regressions did you run?' Period. How many did you run? And, 'Of those, how many found that result that you are reporting here as confirming your hypothesis?' And we've talked a lot about this on the program; I'm not going to go into it now, but you're right: 'fraudulent' is a little strong, but maybe not so strong given what we've learned about the replication crisis. It's most blatant in psychology, but I think it's true in every social science field; and the number of books that are written each year relying on social science studies to give cover to clever and contrarian studies to share at a cocktail party is deeply depressing to me, and a huge part of the problem. That's one way to look at it. The other way to look at it is: It's all cynicism, anyway. It's all just cover for what people want to say, as you're kind of hinting at. These are just--this is what we drape our opinions in. We use our social science--"research studies show"--to give a scientific gloss to our opinions. And, I think that's really bad for science; and it's really unhealthy for our discourse. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Well, not only that: it's unhealthy for democracy. Right? That's fundamentally where my contempt for this type of talk colonizing all of politics. Now, of course we should try to be informed by the best social science that's out there. And George Borjas is actually admirably frank about the limits of what can be known, from the type of work he does. And I actually, I think he's one of the best ones. But it was still shocking to me to find out how few data points these arguments about major issues affecting the American public, how few data points we are actually relying on. There are larger--of course, there are larger studies done on huge, publicly available datasets, and maybe that work a lot better to look at, because they can be checked a little more easily. But I find the studies show discourse to be anti-democratic. Right? It's a kind of priest-craft. Russ Roberts: Oh, yeah-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: bids[?forbids?] the, the common person from what they want to say. Right? Russ Roberts: That's a great phrase--it's priest-craft. And why economists are the highest priests is fascinating to me, given that our track record is mixed at best. And, I don't know, maybe we use more Greek letters and more econometrics. Michael Brendan Dougherty: There's always a Master Science, it seems like. At least from the 20th century onwards. There was, Psychology-- Russ Roberts: had a run-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: Had a run. Economists are having a run. And frankly, the book is pushing against it because I'm more interested in history and in literature than in economics. So--I'm fighting my corner-- Russ Roberts: Yeah, that's right-- Michael Brendan Dougherty: in the world of letters. |

| 1:05:09 | Russ Roberts: Before I forget, I want to talk about your view of, I would say, irony. And I want to read one more excerpt. This is an aspect of American culture I don't see people talk about that much, but I think it's really important. You say, Mass media was my primary teacher growing up. And it taught me and my friends how to conform with one another. It slipped under the table to me a lesson that sincerity is a kind of weakness. That will be used against me. And that any sentiment at all, anything that could expose you to the danger of ridicule or the genuine possession of an emotion, should be double- and tripped-Saran-wrapped in irony. I suppose we do this for safety somehow, as if unwrapped, passion in itself is so flammable it would consume our little worlds at the instant we exposed it to open air. And I've felt that myself many times about our culture--that, the hipster, the person who is cool, is ironic, all the time. That sincerity is mocked. And I just think it is a terrible aspect of our culture. There's a great moment in your book where you talk about a drunken night where someone gets up to recite a poem and cries. And that's--boy, that's prime mockery material. The drunk part makes it a little more complicated. But, somebody who stands up to recite something and finds it so moving that it brings them to tears--we turn away from that in America, I think, a lot. And I think that's a great loss. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Yeah. I was describing a night, in the passage you read from, was I went back to a language learning group that my mother was a part of Daltai na Gaeilge, which is Students of Irish, in America. And there weren't that many young people there. There were a few, and we were kind of ducking away from the normal practice of sharing a party piece--in Ireland, this is very typical; my family does this now, too, in late get-togethers, is--each person, almost, is associated with a song. My father would be "The Rocky Road to Dublin." Or, I would be "The Patriot Game." And you know, you kind of go around the room and you ask them to do their song. So, we're doing this at Daltai na Gaeilge, and the three--the younger people, myself and two others--are ducking this. And I felt like we ducked it because of this cultural formation. You know, and there was an odd way in which even the simplest thing as like romance, the romance between a young man and a young woman, that all of the popular culture around this when I was growing up was in a sense--you might be encouraged to open your heart to another person, but you would have to leaven it with some acknowledgement of how stupid or silly or flawed you were in doing this. As if you couldn't just say, 'I'm in love with you.' Like, the most natural. To me, now, the most natural thing to say. And, so, yeah--I found that this thing that at least had in Irish culture, and it still does to some degree: like I said, it happens late at night, maybe when the doors to the public are closed. You know, that it--there's something deeply satisfying about just saying what you love and trying to honor it in a straightforward way that somehow American pop culture, in a very insidious and probably an unconscious way, almost forbid us to do. Russ Roberts: Well, it's emergent. No one's decreeing it. There's no memo that says, 'Don't be sincere. Be ironic. Make fun of anybody who is overly, honestly emotional.' But that is the, our culture[?]. Michael Brendan Dougherty: Right. But there is something moving--and, of course, the young man I was talking about who was reading this poem, you know, he grew up in West Belfast, which, you know--he was a child born just before the Good Friday Agreement, or not too long before the Good Friday Agreement. So, you know, he would have older cousins, especially uncles, parents who were involved in a horrible section of Irish history and had to moralize themselves for the difficulty that conflict imposed on them, and to get through it. And, like I said, it was almost alien to me. Alien to me as an American, to watch him recite this poem by Bobby Sands and by the middle of it just be sobbing, openly, in front of people he'd just met. Again, it wasn't alien to me as a human. I was deeply moved by it. And, yeah, I wanted to connect with that, that part of myself. And I found it easier to do in this newer language, right? It wasn't just the Irish language of, you know, Gaeilge. It was this Irish language just unwrapped, raw emotion. Which was itself liberating. |

| 1:11:46 | Russ Roberts: Well, if I were Irish, one of my songs would be "Four Green Fields." I would sing that, I would bellow that out, sober even. And I will say--it's an interesting thing--parents, it's part of our job is to embarrass our children. One of my children's great embarrassments is that, in parking garages, which have very good acoustics, when they were younger I would often sing "My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose," the Robert Burns poem, at the top of my lungs, because I enjoyed the sound of it. And that, I think even in ancient times I think was probably embarrassing to children. But, I like to think that when they become parents, God willing, that they will sing in parking lots, or at least sing something with emotion. Because, I think it's like--it's like the line that "Dance as if no one is looking." My view is, you should try to dance that way all the time. Why do you care if someone's looking? It's not--it's better. Michael Brendan Dougherty: And yet, this stuff has still existed: it still exists. Even in America, there are sometimes military ceremonies where people allow themselves this kind of open emotion. There are--in Ireland itself, even today, even as I describe it as in this post-national, anti-nationalist phase--you know, when the doors close at the GAA? [Gaelic Athletic Association?] Club in my father's town and it's just the men who are left in there late at night, people will start singing these old songs. And even young people will listen, kind of respectfully and solemnly. It's almost as if this tradition, song and balladry and national sentiment, is kept, you know, like an axe or a fire extinguisher under glass, in sort of like a 'Break open in case of emergency.' And I've seen that across Europe. I've seen--I got a chance a year or so ago to go to Budapest, and I talked to people about how their culture had kind of been in the 1990s, colonized by Disney. Disney films. Everything had come over from America and filled in all the gaps that the Russians had left behind. But there was this thriving, what they called a Dancehall Movement. And, you know, they, in the cities, they'd bring in, essentially, like peasant national culture into the city for song or for dance. And it took me right back to the early scenes of this book and the early, my early youth of seeing, you know, cultural preservationists trying to document these different dances and local traditions before they expire. And, people anxious to see them. And also, kind of folk blurriness about where it all leads back to. Right? Like, I remember one particular dance was introduced, and it was said, 'Well, this one comes from, you know, borderland between Hungarian and Romanian speakers. So, is it Hungarian? Is it Romanian? You know. Who can really say? Here it is.' And everyone loved it. So, even in that spirit of trying to dwell on or recover this idea of who we are, there can even be this kind of generosity and this acknowledgement that, even as we do this, what we're uncovering is that we're human, and we're also like our neighbors, in some way, too. Russ Roberts: I was talking about decrying the loss of sincerity, and the unwillingness to portray emotion publicly; and yet, I think there are two places where we do allow that in American culture. One is sports, and the second is concerts. People show--they expose their rawness in those two settings. You could argue there is not much at stake there, and that's why it's not like saying, 'I love you,' to someone, which has consequences. So, screaming maniacally for your favorite team, something I do occasionally--I don't want to--I'm not making fun of it. But, you know, that's okay. That's all right. And, in fact, it's one of the bizarre aspects of technology today is that you can watch dozens if not hundreds of people who have filmed their own post-game, post-goal, post-touchdown celebration, post-victory celebration. I'm a Tottenham Hotspur fan; I watched their recent, extraordinary game against Ajax[?]. And the bar exploded near the end of the game when Tottenham scored what was essentially the winning goal. And, you can watch that celebration all around the world, on Twitter and on YouTube. You can watch individuals going nuts in their own living room, versus people in bars, versus parties. So, that's our ritual. We really have some. Michael Brendan Dougherty: You know, it also, it fills in, in a sense, where other places have vacated. I have a good story about this, recently, too. So, my mother's best friend, who introduced her to my father, this London Irish woman, Theresa Murphy. She has worked for and is a passionate fan of Fulham Football Club. And, Fulham, I believe was just relegated to the lower league, right? After it got beat by Newcastle. I'm not sure. But, the Football Club immediately put out this video that was shared across the Internet of one of their local fans and kind of a wordsmith or media-smith, kind of giving this, like, speech about, you know, 'We've known the highs, but we're the oldest football club in this city. And now we're in this low point ; and let me wallow in the lows for a minute and then begin to talk about hope going forward.' And, it was a beautiful video. He's walking along the little stadium, talking about the great white wall for fans that show up for Fulham Football. And, what I realized was the reason this resonates so much is that this isn't just about football. Right? This is meant to speak to something deep within us, this deep thing that we can barely express elsewhere, which is that almost all of us feel at some point in our lives that we've been kicked around, that all of the breaks have gone against us. We're in this pit of failure, and yet we have to moralize ourselves to move forward, in hope. And so it was just--the depth of emotions that this little, two minute montage was touching on--it really was bardic poetry in the oldest sense of the word. You know, trying to give the tribe a meaning after great loss. And, how do you do it? With hope. It was beautiful. Russ Roberts: But I want to extend that, because I do think you're looking at the personal level. And yet, what makes that emotion of that speech more powerful is the fact that we want to be in things together with other people. I mentioned--why am I a Tottenham Hotspur fan? Well, mainly because two of my sons are. And, you know, I did hug a bunch of strangers in that bar after that goal. It's--I wish my sons had been there. They are scattered right now, and I didn't get to watch with them. But, the reason I cared was for them. And other fans, to the extent I'm part of this nation of sports fans. And it's just one of our nations that we have. It's partly a substitute; it's partly a complement[?] to other forms of nationality. |

| 1:21:18 | Russ Roberts: I want to close, let you close, with a comment on America, because America is discussed in passing in the book--culturally, as we've talked about already. Most of the national talk in the book is about Ireland. We recently discussed America's nationalism in passing with Arthur Brooks. I would speculate that the challenge of recovering civility in our political culture is that the American tribe just doesn't motivate a significant chunk of people who live here the way it did in the past. That we have other tribes we've joined, and they conflict. And so, we look at others with contempt; and that's, I think, a horrible thing. I think it's a threat to the country. As I kind of mentioned before, a lot of us think of ourselves as people who just happen to live here, rather than as, say, Americans. Certainly my libertarian friends, some of my friends on the Left, feel that way. You just assimilate when you get here. You are not into the melting pot as an Irish-American. You are nothing. You are just this thing who happens to live here without the burden of that hyphen or the identity--unless you are African-American, which you can't escape it. That's a whole different challenge. But, for many of us, we craft a stateless identity without ethnic roots. And I'm curious if you think, whether that can change. And, if it can't--and I'm not sure it can--what do you think is going to happen here? Michael Brendan Dougherty: I think the premise is a little wrong in what you said. I would challenge it. I would say that the phenomenon you are describing, where, in a sense a lot of us are in these political tribes, or cultural political tribes, that are in this seemingly zero-sum contest to define what is America, what is America going forward. And I agree with you that it's a danger. But, my view of nationality and nationalism, particularly political nationalism, is that it is a product of stress and strain. Humiliation and failur, many times. Or, exaltation. And that, because America is this global superpower--and we can arguably lose wars: we can lose a 20-year war in Afghanistan, hand it over to the exact same tribal people that we went in there to fight, afterr 20 years; and there is no diminishment of American wealth or prestige that's noticable-- Russ Roberts: Or hubris. Michael Brendan Dougherty: on a day-to-day level. Or hubris. Right. No, no; exactly. No; so I think America is uniquely insulated from the pressures that cause this national, a nationalist spirit to come out. But it won't always be so. Maybe our hubris will lead us into something where, like I said, we're under pressure. I do think a type of American, the so-called Trump voter, core voter in the Primary, felt that their version of America was under stress and strain, and so voted for-- Russ Roberts: That's certainly true of Brexit voters as well. Michael Brendan Dougherty: articulated that loss. So, I do think that that nationalist strain--I think there are a lot of reasons for it. It's not just--you know, it's immigration, it's immigration combined with low native fertility that gives you a sense that you are not actually a part of the future where you live in any meaningful way. But it's also this larger reaction to, you know, a kind of internationalist political consensus that I think was anti-democratic in spirit in the last 25 years. So, that I think is bringing it out a little bit. But, that sense of American nationalism--when was it strongest? It was strongest during the World Wars. It was strongest in a period after the Civil War, or after the War of Independence. And then it kind of fades away, and these other internal cultural battles come to the forefront. So, I think people will recognize across their partisan divides, their cultural war divides, their commonality as Americans when we feel that the common inheritance that it is to be an American is in some way under threat. I just don't think America is in that position now. |

| 1:26:29 | Russ Roberts: I guess I had a different point that I was trying to make, although that was interesting: it was not quite the way I was thinking about it. You reacted to the populist version of nationalism; and I do want to alert listeners to, if you missed it, the episode that we did with Yoram Hazony on his book The Virtue of Nationalism, which touched on some of these themes. But I was actually [?] something more related to what I talked about with Jill Lepore, which is: What's our story? You talked about the Irish story here in this book; and it's really interesting. Many of us don't have an understanding, much of an understanding of Irish history. It was very powerful and interesting. But, what's our American story? What's the story we tell ourselves, that we have in mind when we say, 'I'm an American"? And I think we had that story--again, there are groups that were excluded from it, obviously, in horrible brutal ways. So, they have a different story: which I get and deeply sympathize with. But, for the so-called mainstream "average" American, whatever that means, you need a story. And the one--I just sort of hinted at one. For some people there's a story; and then there's a footnote, that we didn't live the story fully for Native Americans and Blacks. So it's an imperfect story; I can't totally celebrate it. But, I can celebrate it a lot. You know, for this and that. Or, I could say, for example, 'Sure, we never lived up to, that all human beings in our borders were entitled to life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness. We enslaved people. We had a culture that made it harder for women to express themselves politically as well as, say, culturally and socially and professionally. We oppressed and killed Native Americans. But we had an aspiration toward greatness that we could be held to account for.' And that's an American story. You might disagree with it; you might think it's dishonest; you might think it misses a lot. And you might pick a different one. But, that's a story that we can tell ourselves, about who we are. That we aspire to greatness. I feel like that's dying--that whole idea, here. And I'm not sure we can survive the death of that story. Or even a story. It doesn't have to be that one. It has to be a story. Otherwise there's no nation. Michael Brendan Dougherty: It is--I do agree. And my book was written a little bit with this anxiety at heart, too. But--like I said, I think there are--I don't think we can predict what stresses and strains will come to America in the future. We can guess: like, I can guess that China is this rival superpower--not just this rival military and industrial power, but as a rival model for statecraft--I think could exert pressure on us. And that what happens is that this--you know, what happens in the Irish story can happen here. There are lots of themes in Irish history that are still submerged, or that didn't come out in the 1916 Rising. Like, they picked up on the 1798 Rebellion, which was mostly led by Protestants--Protestant Irish Nationalists. But it didn't pick up on the, like, Deism, or other aspects that were buried in the thing. They focused on the Republicanism and on the question of political sovereignty. And I think just as the same way--in America's future, whatever happens to us, whatever befalls us, suddenly the parts of the American story that are relevant to that will suddenly be jumping out as highlights in our consciousness. And that's how we'll build out in the future, I think. Like I said, it might be a story of liberation: and so, Lincoln might feature bravely in that. It might be a story of political fight for independence of action and sovereignty, and so the Founding generation will stand out. You know, I don't know. It might be a struggle with tyranny--in Europe, or something. And suddenly FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt] and that story of an increasingly diverse America shaped by immigration coming together as one will be highlighted. Something like that will happen to America in the future. Something, some struggle, some stimulus that will bring out our sense of our nationality, and will bring out what's valuable in it, in that time. Whether it's a sense of liberation, a sense of better justice or equality, we will find those--or whether it's some great compromise, some great democratic compromise--we'll find stories in our history that resonate with that. And so, you re-tell the story again. And, that's only human. |

Author and journalist Michael Brendan Dougherty talks about his book My Father Left Me Ireland with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. Dougherty talks about the role of cultural and national roots in our lives and the challenges of cultural freedom in America. What makes us feel part of something? Do you feel American or just someone who happens to live within its borders? When are people willing to die for their country or a cause? These are some of the questions Dougherty grapples with in his book and in this conversation.

Author and journalist Michael Brendan Dougherty talks about his book My Father Left Me Ireland with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. Dougherty talks about the role of cultural and national roots in our lives and the challenges of cultural freedom in America. What makes us feel part of something? Do you feel American or just someone who happens to live within its borders? When are people willing to die for their country or a cause? These are some of the questions Dougherty grapples with in his book and in this conversation.

READER COMMENTS

Richard

Jul 16 2019 at 8:58am

Toward the end of the podcast Russ asks about the glue that holds America together as a nation. He acknowledges the creedal ideals in the Declaration of Independence (for instance), but seems to conclude that the ideals are merely aspirational and that isn’t enough. For one thing, they were too often breached through the country’s history. So Russ suggests that America needs a common culture to establish its national identity.

I think the story is more intricate than that. America is a creedal country defined by its ideals of equality, individual liberty, and limited governance legitimized through the consent of the governed. Of course, these ideals aren’t uniquely American, but they are perhaps most intensely American. The enlightenment project of pressing an evolution of more closely meeting these ideals over the decades and centuries through ever greater enfranchisement of excluded groups is a living tribute the creed. Martin Luther King expressly addressed this process when he challenged America to “live out the true meaning of its creed.” That challenge was echoed during and after the Civil War, when women won the right to vote, when gays gained social acceptance and the right to marry — and in smaller, bottom-up ways when, for example, a Somali refugee was elected to Congress in 2018. In fits and starts, America has responded positively to pursuing its national ideals.

Coincident with this evolution over the past 240 years or so, people from increasingly diverse origins have immigrated to America over the years often to seek greater tolerance and acceptance than they encounted in their lands of origin. They were prepared to embrace the American ideals that promised that they and their kids could become full members of the American community.

Of course, American culture has emerged alongside America’s creedal core. That culture reflects shared community values and entertainments arising from those who import diverse features of culture from their home countries. E Pluribus Unum and all that. Charles Murray has emphasized the relationship between economics — a strong, uni-modal middle class — and the development of a shared American experience, as well as how the increasingly bi-modal income/wealth distribution has fractured that commonality.

Moreovver, to some, inevitably, the dynamic process of American inclusion demanded by the nation’s core ideals has caused disturbing shifts in the sands of shared community culture as that culture embraces elements brought here from abroad — elements that may seem very foreign to those who don’t see inherit merit and wonder in diversity. Sometimes the sands shift as a product of expanding internal inclusion, for instance as the LGBTQ community has integrated as full participants in society threatening those see their lifestyles or conduct as unacceptable morally or in some other way.

So yes, the impact of living out the true meaning of our creed disrupts culture in a way that might be less evident in a conventional “blood and soil” society — and these disruptions sometimes affect social cohesion and national identity. Yet history tends to show that over the generations significant cultural changes are accepted and the nation moves on better for more fully striving to embrace its ideals.

Pete Miller

Jul 16 2019 at 1:46pm

This episode helped me focus thinking I’ve been doing about the mixed benefits of some kinds of cultural heritage. Of course, every functioning human being has and needs culture. The ability to accumulate and transmit culture is the adaptation that lets us survive instead of claws or flight or being able to desiccate and survive under an ice sheet for millennia until the weather improves. Culture is everything we learn from other people, including those who came before us and those we share life with now. It’s useful to think of it in a few categories.

Technical culture is all the “how to” stuff. It contains all the instructions we need to survive. Which mushrooms are safe to eat. Methods of starting a fire. Instructions for filling out an apartment rental application. Without these elements of culture, humans starve or die of exposure shivering in the cold.

Aesthetic culture is, to some extent, the “why bother?” stuff. It captures emotions and zest for life and moves it down the generations. Hamlet. Super Mario Brothers. The tune and lyrics to Itsy-Bitsy Spider. Without these elements of culture life would be dull, perhaps intolerably so.

Identity culture is how we know and signal which groups we belong to. As humans, we are deeply and necessarily social creatures, and the majority of us need some sense of belonging while the functioning of groups of humans requires some kind of social cohesion. Face to face contact with other humans is an important part of building both of those, but elements of culture that let us signal belonging are also powerful. We are the people who scar three parallel lines in our upper arms to mark adulthood. We are the people who march behind such and such a piece of waving cloth. We are one of the several peoples who never order bacon. Identity elements of culture let us remember and perform who we are in reference to other people and assert that we recognize certain obligations to and demand certain expectations from others in the group.

Individual bits of culture don’t always fall into one bucket. The recipe for sauerkraut is simultaneously: 1) A practical method of having edible greens in winter in the frozen north, 2) The pleasing tang and crunch in the work of art that is a well-made reuben, and 3) An opportunity to signal my group membership – in this case either as a German American or as a contemporary urban dweller who shops at the trendiest stall of the Dupont Circle Farmers Market (or in my case, both).

Some form of identity culture is probably just as essential to life as technical and aesthetic culture. Groups of people are exponentially more effective than individuals. As has been pointed out on EconTalk many times before, self-sufficiency is the road to mere subsistence; specialization and interconnection the highway to wealth. Those who share elements of identity culture find it easier to build the bonds of trust that are required for interconnection and exchange.

It is an open question, though, whether long-established constellations of identity cultural elements – coordinated collections of religion, dress, cuisine, personality traits etc that you might find as columns in a 19th century geography book with one row per nationality – are the only constellations of identity culture that can do the work. There is often some baggage that comes with a “traditional” national set of identity cultural elements. (I put “traditional” in those quotes, because many nationalities are of relatively recent coinage and sometimes backdate their own legacies by claiming continuity with identity cultural constellations that are documented as older.) Often, there is a baked in disapproval and distrust of people embracing some other nationality. Those baked in divisions between adherents to different constellations of identity cultural elements can limit the scope of interconnection and exchange and even lead to violent conflict, and violent conflict is potentially so much more damaging than it was in the past that a threat of it has to be taken with some seriousness.

Owning my priors: This concern has been salient to me for a long time. When I was in high school, I was a conscientious objector from pep rallies because school spirit felt too fascist for my tastes. That was probably an overblown concern but I am still made uncomfortable by large groups chanting slogans in unison even when I agree with the content of the slogan.

To the extent that there is a cosmopolitan movement (and mostly we’re just a bunch of life-of-the-mind types each doing our own thing. If we have meetings, no one has ever invited me), its goal is to create a broadly available identity culture constellation that anyone is welcome to adopt alongside (not over or instead of) any other constellations they participate in. The goal of this broad, openly available constellation is to permit the creation of a very large definition of “we” that represents a large field for interconnection and exchange with fewer baked in sources of conflict. Of course, we all remain human, so to some extent, the cosmopolitans become a tribe who want to engage in rock throwing with the nationalists, but the intent is good.

And probably, most of the nationalists have good intentions, too. For them, there is no open question. Nationality is the only kind of identity cultural constellation that is up to the job of holding people together. All these synthetic constellations – cosmopolitanism, multi-culturalism, Europe – are made of tissue paper and won’t hold together when the going gets rough. Without patriotism, a shared set of aesthetic cultural elements, and shared expectations of behavior in private life, governing institutions will lose legitimacy and the spheres of collaboration will shatter.

Both cosmopolitans and nationalists want to support social cohesion and well-functioning institutions. Each group is just finding different potential failure states more salient and responding accordingly. I don’t know whether that can represent enough common ground to cool some of the opposition, but it at least seems like a gleam of hope.

I hope it is helpful to recognize that an established constellation of cultural identity elements is, at the same time, a useful scaffold on which to build one’s own individual life and to some extent a burden the weight of which may impair helpful innovation. Every individual has to navigate that tension. And interestingly, even though an individual human being can accomplish so little alone, the larger, more powerful social groups we participate in can only accomplish anything because of the personal decision making of the individuals that make them up.