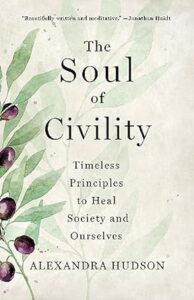

| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: September 14, 2023.] Russ Roberts: Today is September 14, 2023, and my guest is author Alexandra Hudson. Her Substack is Civic Renaissance, and she is the author of The Soul of Civility: Timeless Principles to Heal Society and Ourselves, which is her topic today. Alexandra, welcome EconTalk. Alexandra Hudson: Thanks, Russ. Big fan. Glad to be with you. Russ Roberts: Thank you. |

| 1:00 | Russ Roberts: We're going to start with how your book opens, which is contrasting civility with politeness. Most people use them interchangeably, but you, throughout the book, are eager and I think correct to point out that they are not the same thing. So: what's the difference, and why does it matter? Alexandra Hudson: So, I was raised in a home that was very sensitive and mindful of social norms. My mother--she's called "Judi the Manners Lady"--and I learned through writing this book that my mother is one of four women named Judith who are internationally renowned experts named Judi. One of the most famous is probably Judith Martin, the Washington Post columnist, but there are two more plus my mother. And so, being raised in this home mindful of social norms, I'm constitutionally allergic to authority. I just don't like being told what to do. I [?don't?] like reasons for why I'm asked to do things. And so, I always remember questioning social norms growing up. And, yet my mother's example of hospitality, of graciousness, of just other-orientedness plus her formal instruction and the ways and means of manners and politeness. She kind of promised that these would lead to success in life and school; and she was generally right. And, that was the case until I found myself at the U.S. Department of Education. I had taken a role there; and I was confronted by two extremes that I was not prepared for. On one hand, I saw the people with sharp elbows and who were willing to step on anyone to get ahead and gain proximity to power. And, on the other hand, I saw people who I first thought were my people. These are the people that knew the ways and means of politesse, and they were suave and well-kempt. But I learned that these were the people that would smile and flatter me one second and then stab me in the back and others in the back the moment that we no longer serve their purposes. And that really threw me. At least with the overtly aggressive people, I knew where I stood with them and I knew to avoid them if at all possible. But, this disconnect between inner and outer manners and morals really threw me, because one thing my mother had said growing up was that manners were an outward extension of our inward character--which is why she cared about them, why she's called the Manners Lady, why she has dedicated her life to moral and character formation. And, yet I was confronted with this disconnect: people who were seemed good and nice but were ruthless and cruel. And, it was after I left government that helped clarify for me that there is this essential distinction between civility and politeness. That: politeness is manners. It's etiquette. It's behavior. It's the external trappings of politesse. Where, civility is something richer and deeper. It's a disposition of the heart that sees others as our moral equals and worthy of a bare minimum of respect by virtue of our human dignity and shared personhood and equal moral worth as human beings. And that, sometimes, actually respecting someone requires being impolite--requires breaking the rules of etiquette and propriety and politesse in order to respect them. Like, telling someone a hard truth or engaging in robust debate instead of polishing over difference, or averting--sweeping a difficult conversation under the rug. Actually, the respectful thing to do is to have that conversation. And, today we have two groups of people: one that longs for this golden era of gentility and chivalry and politeness. You know, like, 'Why can't we just get along like in the good old days?' And, then we have this other group and contingent that thinks that civility and politeness is the root of all injustice in the world. It's a tool of patriarchy, a tool of people in positions of power to silence the powerless and keep them powerless. So, we hear these two competing factions; and yet both make a crucial mistake--is that they conflate these two ideas of civility and politeness when they're very different. And, it's important to make this distinction that we know as a society: what is the mode of conduct that we want more of and what do we want less of? |

| 5:30 | Russ Roberts: And your mom was very good at, I suspect, inculcating politeness in you--because she was very focused on manners. Do you attribute your civility to her as well? I don't know you very well. I think we've met in person once or twice very briefly. You strike me definitely as a polite person, and your book suggests you are also a civil one, or at least one who strives to be civil. Do you think that came mostly from your mom also, or do you think it came from elsewhere? Alexandra Hudson: That's a great question, Russ, because politeness on its own is not inherently bad. Its behavior, right? But, it's a tool. It's a technique that can be used for good or for ill. It can be used to mask--it's sort of a Machiavellian spirit that's wanting to use behavior, polished technique, to manipulate others; or it can be a capstone on the disposition of civility that sees people as worthy of respect and it can facilitate difficult conversations. To your point, I think my mom--she embodied both really well. And she definitely embodied the other-orientedness, the sacrifice for others, the love of others, the hospitality that is such the mark of a civil spirit. But she's nice and she's kind. And people are often really caught off guard by her, and my grandmother before her, because they're, like, 'These people are too nice. Like, what's going on?' But, she really just loves people; and that's why she's dedicated her life to what Dale Carnegie, the author of How to Win Friends and Influence People, called the fine art of getting along. She just has this zeal for people in the human condition and wants to connect, wants to bring people together. And, she's done that in such a beautiful way with her life. And, I'm grateful to her example. |

| 7:33 | Russ Roberts: So, of course, you--as all human beings--are a product of nature and nurture. You grew up in the home of your parents. You saw examples of the kind of thing you're talking about. And you are their genetic offspring, I think: I'm assuming you're not adopted. But do you think that the character traits that you urge in this book, which are wonderful ideals: respecting other people, treating them as your equal, giving them the benefit of the doubt. I think for many people these come naturally, these traits, and they might aspire to do better at them, but they're going to struggle. How much of it do you think is just one's nature? That, to put it bluntly, there are good-hearted people or kind people, and there are people who are not so kind, they're more self-centered. They're more--a trait you talk about a lot--that there's a lot more self-love in their heart than there is a love for the rest of humanity. How much of that do you think is sort of ingrained? Alexandra Hudson: It's a great question. I'd say my book is very much at the intersection of nature and culture. On one hand the vision of the human condition that I put forth in the book, I draw from my favorite philosopher and thinker, Blaise Pascal, the 17th century French polymath and inventor and scientist. In his Pensées, he says the human condition is defined by "the greatness and wretchedness of man." That we have both aspects with greatness and wretchedness within us, every single one. And, I recount that famous story of the Cherokee grandfather telling his grandson--you know, the grandfather: 'Which wolf will you feed?' Right? 'Is it the wolf that is malicious and unkind in your soul, or is it the wolf that is gracious and generous?' And, that story, there are many variations of it. And, because it, like, speaks to something we all intuitively know to be true: that--again, I love Blaise Pascal's approximation of the human condition, "the greatness and the wretchedness of man." Solzhenitsyn, his famous line, 'The line between good and evil goes through every human heart.' I adopt that in my book. The line between civilization and barbarism goes through every human heart. That's the first chapter of my book--that, it's easy to look to civilization's past and present and look to things like technological advancement, beautiful skyscrapers, sophistication of language, technological achievements. But, Samuel Johnson has a great line, that the true test of a civilization is how it treats the most vulnerable and the poor; and when society--that the true test of civilization is whether it has this milk of human goodness, this basic respect for the equality and dignity of all persons and doesn't put out these racial hierarchies of in-group/out-group, us-versus-them that it's so easy to do in civilizations across time and place. But, to your question about the intersection of nature and culture, I start with that vision of the human condition--the greatness and wretchedness of man--and layered on top of that is my theory of human nature. Which isn't original to me: this goes back to Aristotle and many thoughtful people before me--that we're profoundly social as a species. We long for relationship. We long for community with others. We become fully human in relationship. We know that. And, that's why as long as we've been around, we've come together as a species. And yet, we're also defined morally and biologically by self-love. We are geared to meet our own needs before others. And those two facets of our nature, our intention, and that is why the joint project of human community, of civilization, of friendship will always be fragile. It is never a foregone conclusion because it's in our nature. There's competing forces in our nature. Another great line from Pascal is: 'Man is a Chimera.' And, a Chimera is this mythological creature with this amalgamation like the head of a horse and the body of a cow and different things like that. Like, we're just this conundrum of a species internally; like, we're at cross-purposes with ourselves constantly, and we do things that self-sabotage our own purposes. So, it takes effort. To your point about nature versus culture, that's our nature. The human condition, our human nature is one thing, but through the will, through effort, through habit formation, through education in the home and in schools, that's the culture. That's the cultivation that each soul, each person can and must undergo so that we can bring forth that which is best in us and in others. That's the promise of relationship. That's the promise to human community: that, together we're able to do more than we would independently. Russ Roberts: And of course, we've talked a lot about--in this program--about Adam Smith's vision of this: that we are naturally self-interested. In fact, I view his masterpiece, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, to be why we--asking the question--why we ever do anything for other people given that our overwhelming natural impulse is self-love--not greed, not selfishness, but self-love, self-interest. And, I think denying that is a mistake. I think Smith is absolutely 100% correct, and that comes from a lifetime of observation as well as my own armchair, right? I think we all can understand this temptation we have to self-advancement, self-love. And, I agree with you, that--the way I think of it is: growing up is about recognizing the power of curbing that self-love and taking account of other people; and to build that habit, because it does not come naturally. That habit has to be inculcated either through religion, culture, family, or self-study. There are many ways to do it. They're all hard, and they work in varying degrees. Or to read books like yours, which, of course your book is an attempt to bring more of it into the world. To give you one more quote, by the way, the one I love is Faulkner's Nobel Prize speech. When he got the Nobel Prize for Literature, he said that, I think either literature or art 'is about the human heart in conflict with itself.' I don't know if Solzhenitsyn read Faulkner, but they're not unrelated. |

| 14:31 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about trustworthiness and the role that trust plays in civil society and civilization and what is lost when it can't be relied on. Alexandra Hudson: It's a great point. I was just talking to a friend of mine, Stephanie Slate[?], about this. I was listening to a lecture series on the Hammurabi Code. So, this early example in human history of positive law, right? So, the law that is enacted by a sovereign--some sort of leader in society--to promote peace and prosperity. And, I asked Stephanie, I was, like, 'What do you think happened in ancient Babylon where Hammurabi, the ruler of this time, decided: Okay, now I'm going to write down on tablets these 271 precepts about what justice is going to be?' I was, like, I asked her, 'Is it the case that norms that had previously bound and restrained people's interactions and governed the horizontal relationship between citizens--had those broken down for some reason and therefore they could no longer be relied on? And, so, Hammurabi said: Okay, we have to now have laws with pretty draconian punishments?' This kind of, sort of lex talionis, like eye-for-an-eye ethos in the justice doled out by Hammurabi's Code. You steal, you get your hand cut off--like that kind of thing. And she said, 'Maybe that's true,' or that the norms had degraded such that Hammurabi decided it was time to have positive law in place to keep society intact. And she said, 'Or, maybe it was the case that they were just so widely accepted and followed that they thought: 'Why not? Why not just codify these and have this be declaratively and affirmatively the law of the land?' Just so there's no question about it. Maybe it was preemptive. My husband loves your show. Kian loves your show, Russ. And, he also loves Tom Holland's The Rest Is History. Tom had recently been talking Hammurabi, and apparently there's a third story about why the Hammurabi Code came into being--and other laws, for example. And that story is that it was a power play: that a sovereign--and maybe there's no moral and breakdown in norms--that the sovereign manufactures a problem and then offers a solution and then has your loyalty for life. Like, 'You maybe haven't had anything stolen from you yet, but just in case you do, know that there's a really good punishment in place to prevent against it. So, vote for me next time.' And so, the way to consolidate and maintain power for those in positions of authority, those elites in society. But, I love your question because I explore the role of social norms and rituals and habits of virtue that promote social trust in a way that promotes human flourishing between citizens and in a way that absolutely allows a democracy to survive, and a limited government like ours--and other parts of the world--to sustain, to survive. What is that great line from Federalists? Like, 'If men were angels, there would be no need for government,' right? Like, in an ideal world, there's no sovereign who's threatening you with sticks, throwing you in jail, fining you, so that you obey and treat others with decency and respect. But, that's not the case. Because we have those two wolves within us to borrow that Cherokee line. |

| 18:17 | Russ Roberts: But the key question, I think, is you can trust your neighbor because your neighbor has a set of internal norms to be trustworthy. Or you can rely on the government, to come back to the Hammurabi Code--if that's what it really was. I don't know how often it was enforced, or whether it was just--and people say it's the Ten Commandments, not the Ten Suggestions. So, I don't know if the Hammurabi Code were actually--how much it was enforced. But I think it's an extraordinary thing to live among people who are trustworthy, because it lowers transaction costs and allows you to do some extraordinary things. Here in Israel, more than once I've heard stories of--this is from a friend. He's on a bus and a woman gets on the bus with a screaming baby. And, she hands the baby to my friend without comment, who is standing near the door--just hands the baby to him--and then goes to the front of the bus to pay and comes back-- Alexandra Hudson: Complete stranger. Russ Roberts: What? Complete stranger. No; that can happen in lots of places, but there are plenty of places where it doesn't happen. And, in Israel, I think it's sort of standard. It's not a big deal. No one thinks twice about it. That's a great thing. I don't worry about pickpockets here in Jerusalem. There probably are some. It tends not to be a problem the way it is in certain other tourist capitals of the world. There's a whole bunch of things like that, that are just pleasant. To take it extreme, people walk around here alone, men and women, at 1:00 in the morning, 2:00 in the morning, without thought. They let their kids walk around here at night at 11:00 p.m. at the age of seven and eight and six. And, it's because they trust the people around them. And, that allows a whole bunch of things to happen that couldn't otherwise happen. And, it's glorious. And, I feel like, in America, which is also a very high-trust society, by the way, on average, some of that has been degraded over time and certainly in certain places. And, it's costly. And certainly in commerce: I've talked many times on the program that, I sell you a house, there's a thousand things--it's a long contract, but there's a thousand things that aren't specified. We leave it to civility that you'll not leave the house in a particular kind of condition. And that is, again, glorious because I don't have to use the legal system to force you to be trustworthy. And so, I think it's precious; and it's also fragile. Alexandra Hudson: That's exactly correct. And because of what it means to be human, the gift and curse of being human is that we have this duality--duality in our nature. That means it's always going to be precarious. As I mention, it's always going to be fragile--friendship, but the joint project of civilization itself. The story I like to tell that illustrates this--I compare three stories that have a lot of overlapping themes. Mayor Michael Bloomberg, when he was mayor of New York City, he had this politeness campaign. So, apparently the norms of decency towards the other in New York City had degraded maybe to the extent that they had an ancient Babylon where Hammurabi came down and said, 'We need to institute this litany of new code of justice.' And so, Bloomberg doled out all of these legislations. So, petty legislations, like: You could be fined $50 if you're at your kid's baseball game and you're shouting too loud. Or, you're at the movie theater and you're texting: $50, fine, Russ. You're on the subway and you put your feet on the subway seat: $50, Russ, added to that. And, New Yorkers were outraged. They're, like, 'Who are you?' They didn't like being civilized by their local government. Funnily enough, around this time, Tony Blair had a similar Respect Campaign, it was called, in London. And it was very similar: again, trying to legislate just common niceties, common courtesies between citizens. The most egregious in the Respect Campaign in England was that if you were dubbed, quote-unquote, "a neighbor from hell" by your peers, by your neighbors, you could have your property taken away. That was how bad it got. And so, I love to use those as examples that: Yes, freedom that we enjoy is not a foregone conclusion. It's fragile inherently but also because autocrats past and present have and will always will be tempted to intervene in the horizontal relationship between citizens that is best left between citizens. I call Larry David, the creator of Seinfeld--and my husband and I love his show, Curb Your Enthusiasm--I call him the Defender of Civilization because he calls himself--I don't know if you've seen this show, Russ. I think you'd love it-- Russ Roberts: Oh, I have-- Alexandra Hudson: It's a comedy of manners, right? He calls himself a Social Assassin. He is, like, everyone's inner ego and id. He sees these breaches of the horizontal social contract between citizens--and that's how I frame what norms are. There's a traditional social contract between the citizen and sovereign--right?--and that's governed through the compact, through laws, and through constitutions. But, there's this invisible horizontal one that's bound by mores, and governed by mores and the Larry Davids of the world. Like, do you remember that one about the chat-and-cut? So, Larry David is in line for a buffet--that's his first problem, to be honest with you. Someone comes in line, and the person in front of him--and strikes up a conversation with the person directly in front and says, like, 'Oh, I remember you. How are you doing? How are the kids?' And, Larry says, 'Hey, hey, hey. I know what you're doing here. This is a chat-and-cut. Nice try. Anyone else here, they would have let you get by with it, but not me because I know exactly what you're doing. You're not going to pretend that you know this person and then cut in line. Look at all these decent citizens waiting in line patiently. You're not better than everyone else. Get to the back of the line.' And of course, they deny it and it becomes this whole awkward affair, which is his specialty. But it's true: The people like him, they help keep order in society. Too many Larry Davids of the world would make society intolerable, if everyone is calling everyone else out for every social infraction all the time. But a healthy amount of them, they keep people in check. Because it's really [?easy to?] find excuses to break the rules, these unspoken rules that we just know exist. And, we especially know that they exist when people break them. And, we're like, 'Okay, okay. Whoa.' Russ Roberts: We did that episode on Obedience to the Unenforceable and Lord Moulton's essay, which you reference in your book. And of course, I think that topic--your book is very much in the theme of that essay, which is about the norms we observe and how they hold things together and allow us to interact with each other in pleasant and predictable ways. They're both relevant. It's not just that they're pleasant. They're also predictable. And of course, when you have people who take advantage of them--the cutting in line, and because they lie about their situation, whether they claim it's an emergency or whatever it is--they degrade that norm and they encourage others to freeride on it as well. And, I've never heard Larry David defend it as eloquently as you just did or as you do in your book. So, I'm sure he'll get a lot of presents of your book from friends. Alexandra Hudson: I hope so. Russ Roberts: Let's hope. Alexandra Hudson: I know Larry David: Please send him a copy of my book. That'd be great. |

| 26:37 | Russ Roberts: Let's shift gears: Back to Alexandra Hudson. You write about in the book that you moved from Washington, D.C., which has a unique culture because as you point out, it's a company town. The one company is Government. The currency of that town is power. And that leads to a certain set of dysfunctional and uncivil--even impolite--behaviors. And, you move to Indianapolis. Indianapolis is, although it is a city, it is a Midwestern city, and it is different from Washington, DC. So, talk about how they're different and how that move affected you. Alexandra Hudson: Thanks. The transition from our nation's capital to the Midwest was this surprising reprieve for me. I had just been so disillusioned and naively soul-crushed being in Washington, being in government. And, my husband is from Indiana, which is why we moved back here. And, it was my idea to come. I came home from work very frustrated one day, and I said, 'Let's move to Midwest.' He was like, 'Okay, done. No take back.' So, a few months later, we were here. So, we've been here five years now. And, I had on my mind this vision of bucolic pastures and rolling hills: just, this place of utter tranquility that I needed to contrast in my mind from Washington. And, I was surprised that, you know, it wasn't a company town. People talked about kids and there were just so many other more important things in life. And that was refreshing. Politics wasn't the only thing on people's mind. And then, I was also taught by one particular friend. One day I was approached by a woman with a blonde bob who came up to me and said, 'I'm Joanna. Would you like to porch with us sometime?' And, I had never heard the word 'porch' used as a verb before. But, intrigued--and we didn't have any friends here--I said, 'Of course. I would love to.' So, she invites us to her front porch, and I realized that for Joanna, her front porch was the site of this quiet revolution that she is staging from her veranda, from her grand veranda, of creating community and allowing across difference and allowing people to feel seen and known and loved just by virtue of who they are and not how the world wants to label people--not just by race and political persuasion or where you live. And she curates people across geography, across place, across discipline, to come and just share a space together. The porch is this sort of cultural metaphor, but also a quasi-living room, a quasi-public space where people can just intervene and just have these spontaneous connections. There's this great essay by a guy named Richard H. Thomas called "From Front Porch to Patio." And he talks about how, over the last 100 years in American history, an architectural shift took place: The front porch, these great big verandas where people would just sit out and enjoy their evenings and wave to strangers and passers-by, slowly the front porch moved to the side of the house over a century of architectural history, and then to the back of the home where that became the modern day patio, fenced in. And, as opposed to the spontaneous interactions you had on the front porch, the patio was curated. It was more intimate. It was more exclusive, just your family and friends--whoever you wanted to see was who you'd invite into the porch. And then, more and more things--like, air conditioning and television--bringing people back inside, even further alienated and away from neighbors/strangers alike. And so, Richard H. Thomas talks about how that architectural shift tracks a cultural one from more communitarianism--looking out towards how we can be present and serve the community--to a more individualistic one, where it's more about us and our needs and who we want to be with and what we want out of our lives. And Joanna, from her front porch, is staging this quiet revolution against that sort of atomized status quo, this divided status quo that we find herself. And, you don't need a front porch like Joanna does to be able to do this. It's a metaphor in that it's the disposition of civility, of transforming the outsider to an insider. Like, to a gatekeeper in the inclusive sense, not keeping people out, but welcoming people in. So, Joanna was really transformational for me, teaching me this sort of other way of being, and really in many ways that my mom had taught me before. And it really kind of represents my theory of social change. One last story: When I met Joanna, she hadn't read Marcus Aurelius before Epictetus, but I had. And there's this great story about Marcus Aurelius. When he was emperor of Rome, he endowed four Chairs of Philosophy. For the Epicureans, he endowed the Garden. For the Aristotelians, he endowed the Lyceum. For the Platonists, he endowed the Academy. And for the Stoics, he endowed the Stoa--which is the front porch. That's what the stoa means. And, the theory of social change of Stoicism is: you can't change the world but you can change yourself. And, if enough of us change ourselves, we can change the world. And so, I love that historical symmetry of Joanna embodying Stoic disposition from her stoa--from her front porch--staging this revolution that I think can and will change the world. And, there are lots of people like her across the country--across the world--that are using their lives to sow seeds of grace and compassion in this very broken time. |

| 32:28 | Russ Roberts: Well, what struck me about her and the porch--I loved it. And it struck a chord in me on a different note, which is that a person on a front porch can be a great raconteur. They hang out. They sit in their rocking chair. People stream by over the course of a Sunday afternoon; some of them stop and share a drink or an iced tea or a shot of whiskey. And they listen to some stories. And, that person's porch becomes a magnet because the person whose domain it is, is so delightful. Now, Joanna might be a lovely person and a great storyteller--I'm not suggesting she isn't--but in your description of her in your book, she's a great connector and she's a great networker. The way you described it, she drew you out, found out what you cared about, found out what was important to you, and then worked to connect you to other people who--of course, some of them weren't just coming across her porch--but again, as a metaphor, people she would come across in her daily life. And, I realized I never really appreciated, and especially in 2023, the power of face-to-face networking. I think in our time so much of our networking is digital, and it's very hard for, I think, people to network today. They're not so good at it. And Joanna is an exemplar of both the necessity of a physical space and a certain kind of person who enjoys connecting people to others and get satisfaction from it. That was my takeaway, and I found it very, very interesting. Alexandra Hudson: I love that. And, I think one reason I felt so drawn to Joanna is because she had this radical-abundance mindset that my grandmother and my mother before me had as well. That, there's no such thing as a zero-sum relationship. There's enough for all of us. And, that Joanna, especially in the story I told, she was just secure enough in herself and her position in life that there wasn't--introducing me to someone wasn't at her expense. It was, like, 'No, there's more everyone to go around.' And, one phrase I use about civility in my book is that it is both inherently good but also an instrumental good. It's inherently good because treating others with a bare minimum of respect by virtue of our shared moral status as members of the human community is good for its own sake. But also, having that disposition of civility, it has instrumental goods as well. It can help us have friendship and conversation. I use examples of porching, and also my chapter on hospitality, to show that there's a sort of minimum and a maximum, right? And, Adam Smith, who is all through my book, he has this great conception of justice versus beneficence. So, justice is what you need for a society to survive, right? It's the bare minimum you owe to others. Beneficence--so that's on the spectrum of civility, right? What is the bare minimum we owe to others? Beneficence is this beautiful old word for active goodness, these proactive--and to borrow a term from Catholic theology--these supererogatory acts, these above and beyond acts that are not expected of you but are good for its own sake. The point is that we need justices to survive, like, a bare minimum. But these above-and-beyond acts--you know, Joanna holding court on her porch and having someone over for dinner--these are these sort of above-and-beyond things you don't necessarily owe every single person. An invitation on your podcast, for example. You don't owe everyone that, but it's like an above-and-beyond thing that you can do. Russ Roberts: Naah. That's too much. But, I love that idea and I've never heard it said that way. The above-and-beyond thing is really a tremendous gift you can give someone else when you--it works in business and it works in human relations. In business--I love this--at the Ritz-Carlton, their motto, talking about civility, is a nice example. It's in between, I'd say, politeness and civility. Their motto is, for their employees, 'Ladies and gentlemen serving ladies and gentlemen.' It's a really powerful way of describing--first of all, it's not a service relationship. There is a service relationship in it. It is serving, but there's an equality in it at the same time because both sides--the staff and the guests--have a certain equality. And there's a certain aspirational piece to it: As an employee, you're ladies and gentlemen serving ladies and gentlemen. I love that. But, if you ask someone at the Ritz, 'Where's the bathroom? Where's the ballroom? Where's the green room?' They're not supposed to tell you. They're supposed to walk you to that place. And that's a little tiny example of above and beyond. And, when you can go above and beyond--the trivial way we describe it is: it makes your day. It makes someone's day. But it's so much more than that. It revives your faith in humanity. It's just a wonderful thing. When you're obligated to do something by a social norm but you go beyond the norm--to meet the norm is a high level because the self-love wants you to free-ride on it. But, to go beyond that and to not just meet it but exceed it is such a nice thing, and it's relatively easy to do. Alexandra Hudson: That's one thing I've noticed. I've reflected on that in hospitality context: when I've had a really nice stay at a hotel, I was, like, 'What made it so lovely,' is, like, they anticipated my every need. They didn't just meet my needs or fail my needs, which is not a fun experience. Where you at--that's the worst, where you have to, like, ask for something. And, it kind of becomes this vicious, like, grasping, that taking; and I hate that. But, when they anticipate needs and go above and beyond--exactly what you said. But I think the same is true with the example you gave for relationships. Just thinking about times and personal relationships where they're strained versus flourishing: it's like when they're at their best, it's when there are these proactive gifts of grace and affection and affirmation and joy, and that mutual service that is like not for any reason other than to serve, and to serve and love the other and see the other and know the other. And, times when relationships are weak is when we're inward-focused and we have that sort of zero-sum mindset where I have no energy or time or resources to give. And so, it becomes this grasping. And then, when we grasp, others grasp. I notice this with my one-and-a-half- and my three-year-old. My one-and-a-half-year-old, my baby girl, loves her brother, Percival James. And, Percy will come up and just take something from baby girl; and then she'll take it right back. Right? She meets him right where he's at. And, I said, 'Percy, she loves you and she will do whatever you do.' So, like, if you serve her--like, you are gracious and give to her. So, I have my kids practice, like Percy say, 'After you, Baby Girl.' So he'll say that; then I'll have Baby Girl, Sophia Margo, say to Percy, 'After you, Percy.' And she's barely talking, and it's so precious. But, to your question, Russ, about nature and nurture: That other-oriented disposition is not natural, and it has to be nurtured. It has to be cultivated and maintained and inculcated and reinforced at every aspect of our life; because our self-love is like gravity, and it will always be a part of our lives, a part of our psyche, a part of the human condition. And we have to fight it. We have to resist it. But, thankfully, having rituals and institutions and formative experiences, like, hopefully what I'm trying to give my kids; and also trying to model it for them. That's the hardest part, right? Do as I say, not as I do. That's the easiest thing to do, but modeling service for them or how I serve you to serve my husband or the other people in my life with my work and vocation, that's harder to live up to that, but just arguably more important. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I always say the secret to a good marriage is not keeping score--and it's hard to do sometimes, but this is another example of what we've been talking about--is if you go above and beyond, just an example, say: I'm not keeping score. I'm not going to give you the tasks that you did for me. I'm down, going to do it for you. I'm going to do two of them actually. Just to show you that I don't keep score. |

| 41:32 | Russ Roberts: You mention in the book a wonderful story from a book we talk about occasionally on EconTalk, The Odyssey, by Homer; and you talk about the story of Eumaeus and Odysseus and what we can learn from Homer about hospitality. So, tell us about that. Alexandra Hudson: So, I love this story. So, Eumaeus is someone that hasn't had many privileges in life. Like, he himself is a servant and very poor. And yet one day, he encounters someone who seems even more down in his luck than he, Eumaeus, is. He sees someone who has clearly had a rough go of it, in rags and dirty and beaten down and forlorn. And, he offers this person invitation into his home. Gives him a meal, gives him a conversation. And, only after meeting his physical needs--giving him a bath and new clothes and satiating his hunger--only then does he ask, 'Tell me your story.' But then, he finds out it's his former master Odysseus in disguise as a beggar. And Odysseus is just elated to discover that his former servant was so kind to someone who could do nothing for him in return. Eumaeus is doing kindness to someone who looked even more downtrod than he was. And so there's this beautiful reconciliation between a former master and servant. And, what I love about that story is how emblematic it is of what true hospitality is. Like, you've mentioned the Ritz; I've mentioned having nice hotel stays. Today, unfortunately, hospitality is unfairly reduced to just travel and hotels and dining and meals. But there's this rich and vibrant tradition of hospitality as how we treat others just by virtue of who they are as human beings. So, what I love about the story of Eumaeus is that across history and culture, there is this moral norm of how we treat the stranger in disguise. And this is the trope: that the stranger, you don't know who they are. And, this is such a value time and time again in The Odyssey--that The Odyssey, it's all about manners. It's all about how you interact with strangers and how you welcome people into your home and the rituals and norms. And, for the part of Odysseus, how he adapts to the norms and expectations of different environments. You probably know this, Russ, but the word used to describe Odysseus in the Greek more than anything is Poly-metis. Right? So, 'poly' meaning many; 'metis' meaning practical wisdom. Poly-metis, because he's so resilient and adaptive. He's, like, 'Okay, what does this situation and person require of me and how am I going to adapt to thrive in this sort of environment?' Like, social norms and rituals require--surviving requires--adaptivity. And so he really embodies that. But, this notion of the stranger in disguise and what we owe the other just by virtue of our common humanity, you know, it's really interesting to think of how hospitality has changed across human history. Again, we think of hospitality as just going on trips and staying in hotels. But the story of Eumaeus was in a time when being a person that was away from your home was a death wish. Like, you're literally at the mercy of the people that you're surrounded by, and it's an incredibly vulnerable position. It was very uncommon. It was expensive and it was not safe. You couldn't carry money with you. We didn't have easy trains and planes, no automobiles. We didn't have credit cards to make for easy means of exchange. So, it was very dangerous, very treacherous. And so, there did evolve from that necessity, this sort of universal ethic that you do see across history and culture to take the stranger in. And, that's a really vulnerable thing to do. Etymologically, the words 'guest' and 'host' are linked in Latin and German and Old French because of this mutual vulnerability that unites the guest/host relationship. For a guest, it's really vulnerable to go into a stranger's home. You don't know what they're going to do when you're asleep. For a host, it's really vulnerable to let a complete stranger into your home--for the same reason, right? And, I love this, that the word, the Latin root for hospitality, is hospice, which means guest and host in Latin, but it's also the root of hostile. And so, there's this duality in how an act of hospitality can go. We are less dependent on others than we have been in past eras when we're traveling. And we have less--Putnam and many others, Robert Putnam, they talk about how we are less hospitable in how we just let people into our home. It's just easy to be very utilitarian with our time. We're busy. We have kids. We have work. We have projects. There's always excuses not to just come together for an unstructured evening of food, wine, conversation or it just doesn't have to be anywhere--or on a front porch, right? We're so hyper-utilitarian with how we spend our time that unless there's an obvious output--right? like, talk about networking or some advantage, getting in proximity to people that are going to help you--you know, we're very jealous with our time and we're very utilitarian. But, you miss out on such beautiful and unexpected gifts when you don't open yourself up to those opportunities. And, one story I tell in my book: like, I say we aren't like Odysseus anymore, where we show up and we are strangers on someone's doorstep. Because today, if a stranger shows up on your doorstep, you're going to be, like, 'Okay, there are public services for you. There's a shelter.' We don't do that anymore because of the era we live in, the institutions in place. But, I tell this story of a time when my husband and I--I was in grad school in London. Kian, my husband, was at law school in Connecticut. I was a Rotary Scholar, and it was my turn to plan this trip, so we went to Ireland. And, I had waited way too long. And so, all of the hotels that were available [?were out?] of my price range as a very poor student. And I had reached out to the local Dublin Rotary Club and said, 'Hi. Does anyone in the Rotary Club have a guest room or any suggestions for--we're coming next weekend? Would really appreciate it. I'm a Rotary scholar.' You know. And, we were just given a name and an address. And, kind of showed up at this doorstep, had no idea what we were getting into. And, we knock, and Paolo opens the door and ushers us into another world. We're in the heart of Dublin, this beautiful brownstone, and all of a sudden we're ushered into Modena, Italy. There's this Italian family, complete with--and they had brought their entire life from Modena to the heart of Dublin. They had their wine cellar. They had their Parmesan cheese wheel. The grandmother was in the kitchen rolling pasta for us for dinner. And, like, we joke that no one has ever gone to Dublin and eaten as well as we did because we didn't have any--we just had Italian the entire time we were there. And that, like, talk about a time of just enjoying this surprising abundance and just this surprising relationship. They're still wonderful friends of ours. We had no idea what we were getting into. It was very vulnerable, very unexpected, and yet it was so beautiful. We've since gone to visit them in Luxembourg, and in Modena, where they're from in Italy. And it just became this beautiful relationship that started out of this place of mutual uncertainty and vulnerability that we were united by, to that etymology of hospitality. And, it could have gone really bad, but thankfully it went really wonderfully. And we were just both--we were very, very blessed and very grateful for that. But again, we don't need one another often. And so, we don't--we miss out on experiences like that. So, that was just--you know--I haven't done that since. We haven't needed to show up at someone's doorstep for a place to stay since then, since we're not poor students anymore. But, that was just a beautiful example of someone who took us in when they didn't have to. And, it was just a beautiful relationship as a result. Russ Roberts: There are people who talk about the virtues of couch-surfing--going from home to home and crashing on someone's couch, often a stranger. It's a very interesting modern development. I think the tragedy of--we talked earlier about trust. Most of us struggle to take a stranger into our house because we don't trust them. It's not that we don't want the burden of a person's extra mouth at the table or that the shower is going to be full at--busy when I need to take a shower. It's that the person could be dangerous. And that's such a tragedy of modernity. And maybe it's no different. Maybe it's an illusion. I don't know. |

| 50:44 | Russ Roberts: Let's close and talk about education. What is the role of education--and by that I mean schools--in fostering or cultivating civility? Alexandra Hudson: So, the final chapter of my book is called, is about civility and practice. A lot of the first part of my book is about why civility supports the tenets of a free society, like integrity, promoting social trust, like tolerance, like civil disobedience even, like respect across difference. And, then, the final section on hospitality, which we just explored and on education is, like, 'Okay, what does this mean in practice? What's the application of this?' And, I say hospitality is, like, the beautiful manifestation--like, the fruit of civility. You have a disposition that sees the personhood of the person in front of you, and you want to honor that. You see the gift of what it means to be human. You want to honor that. And, the fruits of hospitality come from that. And, in the realm of education, I tell the story of a charter--a public charter school--called the Great Hearts Academy. And they're one of the largest charter networks in the country. And, they have this vision of education that has kind of been lost in modernity. It's education as soulcraft. It's orienting our loves. One person that comes up a lot in my book is Saint Augustine, who has this concept of the Ordo Amoris. And that's what he thinks education is--ought--to be. For Augustine as a theist, that we have to rightly order our loves. Like: 'Love God, love others.' That's the dual commandment that Christ gives us in that New Testament. But, Augustine says--and he gets this from Plato--that the just soul is the rightly ordered soul. And the just society is comprised of citizens who have just souls. And, the just soul--for Plato and also Augustine--is the rational part of the body, the head ruling the appetitive part, the belly, through the chest, through the courage, through thumos. And so, that proportion, that ordering of our loves--of our passions--is what comprises a just soul. And citizens who have just souls comprise a just society. The philosopher came up top ruling the Democratic desires money through the Praetorian class. And so, what's interesting about what Great Hearts is doing is they say, 'Our job here as an educational institution isn't just filling kids' heads with facts. It's teaching them how to be human, but also how to be humane. It is ordering their love so as to cultivate their humanity. And, this is key: As they cultivate their own humanity, they appreciate the humanity of others.' And that is--I link this concept from the ancient Greek idea of education called Paideia. Paideia was this concept in the ancient world that was--it required unstructured leisure time to cultivate the fullness of who we are as human beings so that we could lead and be citizens and fully actualize in society and be our best selves. This idea manifested itself in the Latin world and the Roman Empire and the concept of humanitas--and this is the where we get the Humanities from--that this was the mode of education, dabbling in rhetoric and poetry and art and literature and math and geometry that well-rounded us. What cultivated all aspects of our humanity and made us fit to serve, to serve our community, to serve. And, this of course, back then in the Roman Era was the education afforded to men who were set for leadership positions. In the Renaissance, this idea manifested itself with the Renaissance Italian humanists and the concept of civility. They were all about hearkening back to this older mode of education. Education as soulcraft, as ordering loves, as cultivating humanity. And, this was the education that was promoted amongst elites during the Italian Renaissance. And so, I love that there is this intellectual lineage that's still being practiced in some parts of the country today, including in a mass charter school network, like the Great Hearts--that sees their mission in life, their mission as part of their institution, is to cultivate the humanity of their students, making them not just more human, but also more humane--more gentle, more serene, more kind to their fellow human being. Because there is unfortunately so much malice, so much cruelty, that I argue in the book comes from when people insufficiently appreciate the gift of being human. When we don't fully appreciate our own humanity and what a privilege that is, it makes us harder to appreciate the humanity of those around us. It makes it easier to dehumanize them and debase them. And, this is a key argument of my book and my argument for civility is we hear a lot today--you know, the stakes are too high for us to be civil to the other side, that it is too important. All bets are off, and we have to do anything we can to win. And, nice guys finish last. You know, that kind of rhetoric. And, my argument is that when we are cruel or malicious or debase or dehumanize others, we don't just hurt others. We debase and dehumanize ourselves, too. Socrates said that 'virtue is its own reward, and vice its own punishment.' And, the same is true for civility. Being good and gracious and kind to our fellow human beings, tolerant and respectful for them across difference, that is its own reward. And being malicious and cruel, that is its own punishment. It doesn't just hurt the other. It hurts ourselves, too. And, I get that from Dr. King's letter from a Birmingham jail who makes the exact same argument about segregation. Segregation doesn't just hurt the segregated. It deforms the soul of the segregator. So, just as civility is mutually enobling, incivility and cruelty is mutually ignobling. |

| 57:20 | Russ Roberts: And, what it's really about--I mean, I think 'soulcraft' is a beautiful, poetic way to say it--and the old-fashioned way to say it is 'character.' We spend a lot of time as parents, my wife and I, trying to build character in our kids. I don't know if we were successful or not. It may have been a mistake to try to do that deliberately. I don't know. And, I don't know how successful we were. But it used to be that that didn't just take place in the home. It was part of school. I think that was certainly true in, say, 19th century America and certainly early 20th century America--I think. Maybe I'm being romantic and nostalgic. But, I don't think it's part of modern education. either at the K-12 [kindergarten through 12th grade] level or certainly in college. College is much more vocational in America than it once was. And, I think K-through-12 is just feeding into the college. It's prep for vocation. And, there are some advantages to that for certain types of people. But I think something precious is lost as religion struggles in America and as schools walk away from character as a part of their job. We're much more likely to, I think, head toward self-love and less toward being appreciative of the people around us. So, it seems like that's kind of important. And, it's interesting that there's private schools, certainly religious schools. I have familiarity with Jewish schools. Jewish schools are obsessed with character formation through Jewish observance. You can debate how successful they are. It's an interesting question. But they're not unaware of it. And, similarly, it sounds like there's charter schools that do it. But the public school system, that does not seem to be the mandate. And, that seems to be, for better or for worse, mostly for worse, I think. Alexandra Hudson: It's a really great point. One thing I've noticed with all of the discourse around character education that's currently happening is they take the values out of it. They neuter it of any sort of normative value, and they reduce it to resilience and grit and perseverance. And, that is because that's inherently a challenge with public schools. Right? Like, in a pluralistic society like we live in, there are going to be competing norms and competing values. They try to say, 'Okay, let's keep the good consequence of values, but take away the value language of it.' And, that's why I really enjoyed learning about this charter school network that was able to keep the values while also being in the public school system. And, they're in three states. They serve, like, 20,000 kids. They're a serious player in this space. But, the fear is that the values that you purport, like no school wants to be accused of shoving anyone else's values down another kid's throat--their own values down another child's throat. But the difficulty is, we need values in a society to flourish. Like the value of being pro-human: I hope that never becomes controversial. And, that [?] virtues that cultivate our humanity, that make us our best self, like courage and prudence, that again, help us be our best selves in the world. It is too bad that these things are controversial, and that there is such a fear of talking about the role of values and normative values in the public system, because we need them. Education is explicitly value-laden and linked. It cannot not be. And, I affirmatively make that case in the book. It has to be. Russ Roberts: But to be fair to the public school system, now, I'm going to disagree with myself a little bit. There are a lot of values in there. They're just not the values that there used to be there. And, that I think is a legitimate change. So, to pick one, anti-bullying is a huge obsession, I think, in our schools today. And, there are worse things. That's a good thing, more or less: that is a civil value. So, maybe it's just a question of: it's changed and I'm just an old curmudgeon. And, by the way, I went to a public school; I got no character formation in my school system. Nobody lectured me about being a good person or how to be a good person or encouraged me to be a good person from my school. It only came from my home. To the extent it was successful, I don't know. But again, I got nothing as far as I can remember from my formal education. So, maybe it's not as bad as we think. Maybe it's just a little different. Alexandra Hudson: Yeah. I love what you said. That's a point I make time and time again in my book. Like, on one hand, human nature doesn't change. We're the same stuff of person, of people, of human beings that we were 2700 years ago. And that is why, for instance, there are so many lessons to be mined from the oldest story in the world, the Epic of Gilgamesh, which I open my book with. Maybe that's a conversation for another day, or for example, that's why the oldest book in the world--so, Gilgamesh is the oldest story in the world--but the oldest book in the world is the book on civility. It's given to us from Ancient Egypt. It's called the Maxims of Ptahhotep. And, it's 38 teachings written by an Egyptian advisor about the life well-lived, and they're remarkably timeless. They stand the test of time. But, they could be written by Judith Martin at the Washington Post in one of her columns. And, I think that's beautiful that we can feel connected to other times and other places in that way because, again, human nature doesn't change. And yet, society does change in some ways. Like for example, the front porch to patio. There are architectural shifts. There are institutional infrastructural shifts. There are technological shifts that make it easier to indulge our self-love and our nature and become isolated and alienated. And, that disconnect us from others, whether it's the way that our home lives are structured, or how we live our lives on the Internet, just in virtual silos. Just hearing people and ideas that we like and agree with. Those are things that didn't exist 2700 years ago--or 2700 BC, rather--or even 50 years ago, 10, 20 years ago, that do make, I think, pose unique challenges to civility. But, that's a point that I make time and time again in my book, that this is a timeless problem, and it's a hard one for that reason. So, I hope my book offers a few answers. Certainly not all of them, but I do hope that it helps us have a more clear conversation about what the challenges are, how difficult they are, and the role we each have in being part of the solution. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Alexandra Hudson. Her book is The Soul of Civility. Alexandra, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Alexandra Hudson: Thanks, Russ. |

When Alexandra Hudson arrived in Washington, D.C., she discovered that outward behavior is not always a reflection of a person's character. Her disillusionment led to an in-depth exploration of the historical concept and practice of civility, along with a newfound appreciation for not only empathy, but also debate and disagreement in a healthy society. Listen as she and EconTalk's Russ Roberts discuss her book The Soul of Civility, a call for less superficial politeness and more genuine respect for and consideration toward others in the social, cultural, and political spheres. They also discuss the power of social norms and how they can promote human flourishing.

When Alexandra Hudson arrived in Washington, D.C., she discovered that outward behavior is not always a reflection of a person's character. Her disillusionment led to an in-depth exploration of the historical concept and practice of civility, along with a newfound appreciation for not only empathy, but also debate and disagreement in a healthy society. Listen as she and EconTalk's Russ Roberts discuss her book The Soul of Civility, a call for less superficial politeness and more genuine respect for and consideration toward others in the social, cultural, and political spheres. They also discuss the power of social norms and how they can promote human flourishing.

READER COMMENTS

Krishnan Chittur

Oct 16 2023 at 1:29pm

Enjoyed the conversation … (did not know about Coles and what he tried to do …)

I had heard the story of the woman handing her child to a stranger on a bus – and today, it made me incredibly sad – listening to this in the context of what happened Oct 7 … so much has been lost – and sadly what looks like how inevitable it was according to some analysts

“World Peace” – yes a slogan – but how desperately we need it – a truly “Civil World” – here is to hope we get it …

Ben Service

Oct 16 2023 at 7:16pm

I wasn’t really looking forward to this conversation at the start as it had the feeling of being one of the “ah the old days were better, kids these days…” type talks but it was actually very interesting and thought provoking.

The conversation about being a guest and a host and the equivalent risk that both take made me consider a trip we have as a family to Ecuador this Christmas for six weeks, we are a bit concerned about the safety situation in Ecuador but we are also trying to teach our kids that in general most people are nice and in general it is worth taking the risk to trust rather than be fearful. However when you are about to dive into the situation it is hard to act in that way and we are not sure what to do now. We have a motto in our house of safety third (as opposed to safety first), learning and fun come first, but Ecuador is stretching that philosophy a bit.

The other interesting one is about the porch and the patio. I think it is hard in a western culture to reverse the my house is my castle mindset, but then the west has been reasonably successful so maybe the private property rights which I think leads to this mentality out weighs the minuses. Given this though how do you get more community? In my small Australian town we tend to see it in kids sporting clubs where people from lots of different walks of life come together and help each other out without a lot of written rules. The latest episode from The Happiness Lab “Text a Friend… Right Now!” also had some good advice and insights for reaching out to people and the unexpected effects.

Great etymology too, I always find that interesting.

Doug Iliff

Oct 17 2023 at 8:44pm

Regarding civility and public education, embedded in a Free Press column today (also includes interesting comments by frequent EconTalk guest Vinay Prasad) was a funny/sad/depressing clip from Ben Kawaller, who wandered around the UCLA campus interviewing students, and failing to find one with something approximating a moral compass:

https://www.thefp.com/p/niall-ferguson-vinay-prasad-jihad-day?utm_source=substack&publication_id=260347&post_id=138029644&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&utm_campaign=email-share&action=share&triggerShare=true&isFreemail=false&r=7n3hr

Russ didn’t remember any moral instruction from his public education, but I got a ton of it from mine. It did me a lot of good, but by the time my kids came of school age in 1980 the schools were in the throes of “values clarification.” This was a stepping stone to the wholesale abandonment of ethical principles by the postmodern education establishment— recognizing, of course, that some individual teachers still held to the old values.

With a group of like-minded friends, I started a classical school (Cair Paravel-Latin) which, 43 years later, is growing and thriving. Private schools, along with charter schools not beholden to the dominant Zeitgeist, are the hope of the nation.

Doug Iliff

Oct 19 2023 at 7:39am

Dear Editor,

I carelessly failed to spell check my spell checker, which changed “throes” to “throws” and “beholden” to “beholding”. If you could re-correct the corrector, I would be greatful.

I mean, “grateful.”

[Fixed. I’m sympathetic to the problem of spelling-modification by the dictation aids, by the way. Often even after I visually spell-check something I’ve dictated, when it is subsequently rendered in print by the dictation aid (probably heavily AI-assisted these days), what had been correct annoyingly ends up changed to the incorrect. –Econlib Ed.]

Paul Detlefs

Oct 19 2023 at 10:46pm

Interesting conversation. I agree with Alexandra. The distinction I like to make is between “nice” and “kind”. Trying to be nice all the time is frequently false civility. It is important to be kind rather than nice – not the same thing. I think civility or being “honest” with people is being 100% truthful and 100% kind at the same time. That is absolutely possible. In fact, if we are not truthful with people, that is actually unkind because we are hiding the truth from them. We need to tell them the truth in a kind way. Coach Prime at CU told the previous players the truth in a kind way.

There is a great example of this in the book “American Icon” by Bryce Hoffman, the story of Alan Mulally turning around Ford in the 2000s. Mark Schulz, the president of Ford’s international operations, didn’t like Mulally’s weekly meeting. He traveled a lot and wanted to get out of attending. He told Mullaly that the weekly meeting would get in the way of important work in China. Mulally said with a smile “That’s okay, you don’t have to come to the meetings. I mean, you can’t be a part of the Ford team if you don’t – but it’s okay. It doesn’t mean you are a bad person.” That is 100% truthful and 100% kind. That is being truly honest in a civil way.

Jan jones

Oct 26 2023 at 10:58am

Enjoyed the talk on civility. My husband and I always take you along on driving trips. I hope you will soon find a way to address the current events in Israel on a podcast. Thank you for the many educational hours over the years.

Comments are closed.