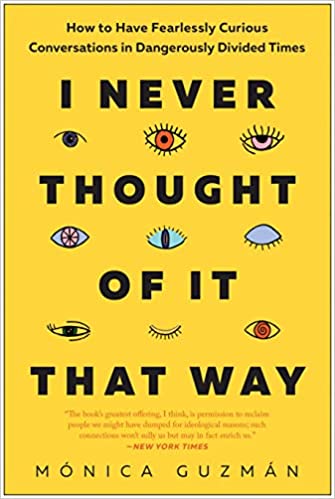

| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: November 23, 2022.] Russ Roberts: Today is November 23rd, 2022, and my guest is journalist and author Monica Guzman. She is a Senior Fellow at Braver Angels. Her latest book and our topic for today is, I Never Thought of It That Way: How to Have Fearlessly Curious Conversations in Dangerously Divided Times. Monica, welcome to EconTalk. Monica Guzman: Thank you so much for having me. |

| 1:00 | Russ Roberts: Now, this is an absolutely lovely book. You are a self-professed liberal; and I've read and interviewed a number of people in this program about the challenge of conversation, the challenge of partisanship, the level of anger in our discourse. And, interestingly, I think all those books that I've read and interviewed people about are written by liberals, but yours is the most--maybe the only one--that is fair to conservatives. There are books that pay lip service to fairness, but as a reader, I felt that you were empathetic to both sides of every issue you gave. And, often you were very careful to give examples on both sides of people who were either misunderstanding or so on. I'm sure you worked at that, and I just want to congratulate you because in many cases I find that challenging for people to do. Regardless of what part of the spectrum they're on--of the political spectrum or the ideological spectrum--they often attribute views to their opponents that are either, I think, straw people, unfair, or the point of their book is to save the world by converting other people. And, I didn't get that impression from you. So, talk about why that's your perspective and whether that was hard for you, as a self-professed person on the Left side of the political spectrum. Monica Guzman: Yeah. This was extremely important to me. It was difficult only because I don't see a lot of models for it, but I am convinced that we need it. So, I thought, as I was writing the book, a lot about my parents. We're a politically divided family. I am liberal, like you said: I voted for Biden and Clinton. My parents voted for Trump twice. And we don't hold back when we talk to each other. And, there have been so many times where I have taken the latest outrage and brought it to my parents because, 'Arrrgh!' Because this has to be the thing. Right? And, then they give me some angle or some question that is a lot less malevolent than where I thought this was coming from on that side. And, it turns the volume down in my head; and I go, 'Oh yeah, I was missing that. I was missing something. All right.' And so, having had that experience so many times made me think: If I allow some of those impressions, the anger to go unnuanced, in my book--if I give one example and then allow the reader to say, 'Oh yeah, that's just obviously because the other side is crazy, evil, or stupid,' then I'm doing a disservice because I just don't think that's true. I think that we fall into that trap frequently in our disagreements and also just when we look at the other side. Russ Roberts: Well, so many people do think it's true. I try, I mean we don't always succeed, but I do try to be empathetic to people who don't agree with me and respectful of them. When did that happen for you? I don't think we're hardwired that way. I think we're hardwired the other way. We spend a lot of time on this program talking about tribalism and political tribes or one form of tribalism. What clicked for you that caused you to be that, I would say, respectful? Monica Guzman: I think a fair bit of it came from journalism. All the times that I've approached some source--you know, not even a particularly controversial story--I've just had a narrative in my head of who they are and what they're going to give me; and I prewrite the story in my head and I know what it's going to be about. And then, we start talking and I'm fascinated by something I didn't expect, or there's a motivation that I didn't see coming. And then, here we go: we're just off on another tangent, and everything's gotten so much more rich because of it. And, that's happened so many times that I guess I've just--it's become sort of silly in my head to judge people without engaging them, to not approach individuals and see what they're really about, to not have those open-ended questions. I think largely it's been about that. In the book, I talk about the difference between puzzles and mysteries. The author Ian Leslie, who wrote a book about curiosity gets into this. And, puzzles are problems that you solve. You already know the shape of the thing you're making. You just have a couple of pieces you need to go find and then put in the right place, plug them in. But, mysteries, you don't know the shape. Every piece you pick up changes the shape, draws up a bunch of new questions. You never really know where you're going. And, that's people. I think that in polarized times we treat each other like puzzles. We read a thought-piece that's written really smartly and we think we now understand this whole group of people. We now have the shortcut for why they do what they do and we can judge them accordingly, and that's going to be okay. But, people are mysteries, and there's just so much we're missing when we do this to each other--including a clear view of the world itself. I think that we are so divided, we're blinded; and we're not even seeing the world for what it is, but for the projections swirling in our heads. Russ Roberts: Ian Leslie was a guest on EconTalk talking about that book. It's a lovely book, and I, of course, love--as listeners would not be surprised--I love the puzzles-versus-mysteries dichotomy. I think it's a really important way to look at most of life. Most of life is a mystery. Puzzles are pleasant because we can solve them. So, we tend to push a lot of things, I think, into the puzzle box when they belong in the mystery box. |

| 6:50 | Russ Roberts: But, I want to ask you about something that you didn't write about. You write a lot about conversation per se, and we'll come back and talk about that because I think that's very valuable. But, I want to ask you about something that isn't so obvious, perhaps. Your book is about political disagreements mostly and particularly partisan disagreements, ideological disagreements. But, some of the lessons here apply equally strongly to something like marriage or friendship. And, one of the things that it took me a long time to understand is that often in our marriages or our long-term friendships, we have a narrative in our head about the other person and we fill in their lines effortlessly for them. We know what they're going to say. In fact, that's often a measure of, quote, "a good marriage": People will say, 'Oh, we can finish each other's sentences.' But, I think sometimes we fall down on the job as partners, spouses, friends, because we leap to those conclusions, assume--as you point out in the book, as we do sometimes about our political opponents--what they're about. And, it's surprisingly difficult to step outside those scripts that we have for each other. And, I just think that's such an important part of being a human being that we don't talk about. Monica Guzman: Oh, yeah. No, absolutely. Absolutely. And, I like that you kind of use the language of scripts because we do that online to each other all the time, too. More and more people take what they see on social media--somebody makes what could be sort of an innocent remark. If you're on the Left, you see somebody lament the looting that happened during protests in the summer of 2020; but you've seen this script before. Russ Roberts: You mean someone on the Right? Monica Guzman: Well, but it could be someone on the Left judging someone on the Left. But it could be anybody. But, yeah, it's you see someone on the Right, perhaps, yes, lament the looting of businesses; and you think, 'I've seen this movie before. What they really want to say, but can't--they're just trolling us or teasing us--is that they're racist.' Stuff like that starts to happen when we do this to each other. When we just predict and we believe we already have the whole story. And so, when we're engaging each other less and judging each other more, that's the swirl. We're going to keep swirling away from each other and keep getting more and more misinformed about each other. I find it interesting: we care a lot about facts and truth, but that doesn't seem to apply to the truth about people's perspectives. That's where it seems we don't obsess about truth. But, I just think that's really killing us because when people feel understood, that's when you can build trust. And without sufficient trust, we can't collectively search for truth. Instead, we'll have different groups of people finding their own truth and then fighting each other about it, developing their own different languages. And, again, we sort of spin apart in this really unsustainable way. So, I feel almost--sometimes I feel like a traitor to journalism because journalism is about truth. And, I have so many conversations with people who are saying things I'm pretty darn sure are untrue, but I don't make the conversation about that. I don't sit there and try to convince them of something that they're not going to be convinced by in this conversation. Instead, I go behind the conversation about truth to the conversation about what's meaningful. Who are they? What led them to these beliefs? What are the concerns and hopes and fears that animate, right? And then, what can I present about how I see those things and how can our perspectives sort of intermingle? And build trust, and build the kind of connection where maybe someday something could cross that makes them see something in a different light, or makes me see something in a different way. It's getting harder and harder to calibrate with each other in that way when we don't seem to prioritize making sure we get each other right. |

| 11:07 | Russ Roberts: I think one of the other perspectives on this that makes it harder--one of the other facts about this--is social media, where, if I ever admit I was wrong or ever admit that I had an imperfect view of the other side, or I've come to believe something different, I get savaged. I recently tweeted something about Elon Musk and Twitter that I thought was pretty innocent. It's pretty stupid of me because--the innocent part of it, whether it was stupid to tweet, I don't know--but I tweeted something about Elon Musk and it didn't cross my mind that there's an enormous--this is the naïve, stupid part--it didn't cross my mind that there are probably millions of people on Twitter, certainly hundreds of thousands, who don't like Elon Musk. Period. And, were going to use my tweet to express that feeling. And, I started getting these bizarre misinterpretations of what I'd written with leaps of logic from what they claimed I'd said. And, I thought--and I'd write politely back, 'Not my point. Not what I said.' Sometimes I'd write, 'I may have miswritten it, I may have communicated poorly, actually what I meant--' And, then I realized: They're not interested in what I really meant. They just want to jump on Elon Musk. And, what was fascinating for me is that emotionally, the disdain I got for my opinion, the one that they interpreted me as saying--I was surprised how much it bothered me that they had misinterpreted. Which is ironic. I'm on the web; I'm on Twitter. I've got--all the time. Don't I know this? And, I realized I don't really go into some of those darker corners. And usually what I've done in that situation, I just block people who are rude or misinterpret me. And, I thought, I don't really need to. I should just try to let this roll off me. And, it was harder than I thought, but I got to the point where it's, like, 'Oh yeah. They're not arguing with me.' They're on a different platform over there, a different grandstand, a different soapbox than the one I was on. I actually like to think I'm educating people. I'm getting people to imagine an idea. They weren't so interested in that, I don't think, and I just--let them be in their own world. It's okay. But, it's amazing how that social media response can motivate your own viewpoints and what you're willing to say and how you're willing to say it. Monica Guzman: Absolutely. I think of a couple things here. The other day I stumbled on a, I think it's from the Talmud, an old quote: Things are not--we don't see things as they are, but as we are. And, Jonathan Haidt has done some wonderful writing and research on social media as sort of a space where we throw darts at each other. And in your example, I thought of a game of dodgeball: something comes and if it's a weapon, I'm going to pick it up. Even if you didn't intend it as a weapon or something I can use to boost up my side or what have you, that's how I'm going to use. I don't care how you meant it. That's how I'm going to use it. And, then I'm going to throw it at somebody. And then a lot of us are going to throw it at somebody; and you're going to feel like, 'What was that?' Right? But, I think it's so true these days that we are so in our own thoughts. This is funny: I think that this thought just crossed my mind. I'm a big science fiction fan, and I grew up reading all the amazing science fiction that was mostly about space travel--that by now that's what we would have worked on, is getting out, getting out of the planet, exploring. But, what we did instead was we took all that technological energy and used it for personal communication. And so, we've created a whole universe in our minds that connect our minds, that connect every thought, that share every thought, and zip it around the world at lightning speed, that create movements and topple governments, but also drive us insane and make our kids more anxious than ever. And, this is the universe we've created, is a universe of our own thoughts. And so, how each of us, the posture each of us takes toward that, that swirling--I mean, it's so funny to think that we are uninformed, but we have never had more information. We've never had more information zipping around us. So, what's going on? Russ Roberts: Yeah. A number of people in the last year, I've noticed, have written with sadness about the naivete we had when the Internet was started. And, I had it for sure, which was, 'All this information--oh, we're going to be wiser.' Right? 'How could it not be the case?' And, of course, there are a lot of reasons, it turns out. I've written an essay on it; I'll link to it. But, that irony is so painful. Right? The idea that you and I can communicate; we've never met, we may never meet. Here we are talk having a real conversation. I'm in Israel, you're in Seattle. That's a magnificent triumph of--in a way, it's so much better than going to Mars. Mars is a pretty tough environment, and this is amazing. And yet, so much of this kind of miraculous interaction is not turning out to be as helpful as we had hoped. Monica Guzman: Yeah, exactly. And so, much of it is psychology. I think, thanks to a rising awareness of this, right? Because technology zips ahead real fast, and it takes us a while to understand what's going on. We now have more information swirling around about our psychology. We are tribalistic. We do sort into groups that are like-minded; and there are consequences: when we share our instincts, we share our blind spots. And, a lot of the story of polarization is sort of that--you know, just spread out. There's valid disagreements, and there's all kinds of problems to solve. But, unfortunately, where we find ourselves now is so afraid and so kind of taken by projections and hyperbole that a lot of our policy is reactionary. A lot of things are rash. They're not that thoughtful. And, one of the tragedies to me is when I think of the extraordinary creative and human capital we have at our disposal--you know, think of how much more educated we are. Public health, despite the pandemic, is still much better than it used to be. All these ways that: we're here, we're showing up. But then the filter of the way we talk to each other seems to take, like, the potential output of 100% and bring it down to 5%. Like, the good stuff coming out of this is just not that great. When you think about everything we have here, we ought to be able to collaborate. We ought to be able to understand each other and get so much more advanced--like, level-up our thinking about these tough problems, understand why they're tough. They put good values into tension with each other. It's not good versus evil. Stop! This is what's dumbing everything down. But, we allow these things to swirl and swirl and swirl because we get something out of it. We get pride, we get prestige, we get status. And it's killing us. Russ Roberts: I've often lamented on here that, what an extraordinary miracle, achievement, of human creativity it was to develop a vaccine in a weekend against COVID. And, yet that scientific achievement has become a political football. Which is really so unimaginable. Of all the things to argue about and to misunderstand, and as you point out, not to make progress. It should be easy. We have access to incredible data. We have ways of bringing people together to share experiences for the purpose of understanding what happened more effectively. And so, little of what we've done is devoted to that which we desperately need for, quote, "the next time." And instead, it's, 'Oh, let's punt this football around. Let me race down to your end of the field if I can, and you'll try to race down to the other end.' And it's such a tragedy. Monica Guzman: Let's use it as weapons. Yeah. It's the same thing as that dodgeball game, again: How can we weaponize this? And, yeah, it is--it is such a tragedy. And, to me, one of the things that shows is that we still have quotes, like, 'Well, it's not rocket science.' Right? We have a sense in our head of what is most difficult. Well, most difficult is probably straight physics, Stephen Hawking stuff, right? I don't know. I think we're in a world where good, responsible human communication is the most difficult and critical skill there is, because those doctors communicating about COVID knew their medicine. Those politicians, there were lots of good politicians that wanted to serve society in this moment, right? But the communication--I've talked with lots of conservatives, lots of liberals--it was the communication that needed work. Russ Roberts: I recently interviewed Agnes Callard, and it's not the first guest we've had a discussion--contentious discussion--about whether human beings are making progress. And, it's clear to me that we're making a lot of progress on the technological side, the scientific side. The communication side is not so clear. And as you say, those are really the hard problems. Being a better human being than you were a year ago, that's immensely more difficult than, say, improving the mileage of a gas-powered car. Monica Guzman: Exactly. Exactly. Maybe we should put a little more attention on helping each other get better at that. The funny thing is: there's this little we can do with the laws of nature to make rocket science itself harder, but we can continually make our own communication harder: because we mix together more. Because now we can talk all the way around the world. We keep making it harder for ourselves. So, that means we have to keep leveling-up. |

| 21:06 | Russ Roberts: And, of course, that's what your book is about. Let's come back to the--actually, I just want to add one more thing. I want to add just a little tiny bit of optimism here. We're a little bit pessimistic right now. I did a Twitter poll this week, for fun, on whether Steve Jobs would be happy or unhappy with how the iPhone has transformed our culture? I did it over a day and a bit. A thousand people voted. It was 53:47 or so, that Jobs would've been happy. And, I call that a very depressing--that's a low number, 53%. And, of course, we have no idea what Steve Jobs would really think. It's more of I think what people think he should feel, given the state of the world. And, one listener, one Twitter follower of mine, wrote--I apologize, I don't remember who it was--said, 'It'll turn out okay. It may be horrible now, or there may be things you don't like now.' And, I have to admit that for myself, if you had-- I'm not, I'm happy there were smartphones in the world. I think it's a glorious thing. But I also see a lot of downside to it. But, his point, which I think is the ideal, most optimistic it can be, is that it's new and we will develop norms to deal with it. Those norms--he didn't write this, I would just add this--maybe a norm will develop as Jonathan Haidt, who you quoted, mentioned earlier, Jonathan Haidt said, 'There should be no smartphones in,' I think he said, 'middle school. Maybe that norm will emerge. Maybe there'll be a norm that, at dinner, or at meals, we will all agree to put our smartphones away. These are personal things that we've sometimes done in our household or in other settings. Keeping the Jewish Sabbath: we put the phone away for 25 hours. Somehow it's easy to do that. But, the rest of the time: Full use every minute, way too much screen time! And so, that's my only bit of optimism. You want to react to that? Monica Guzman: Yeah. The optimism that norms will come. I think you're absolutely right. I think you're absolutely right about that. It's taken me a very long time with these technologies in every way that I've swirled in my personal life, in and out of them, to finally come to a stage where I feel like I'm in control. It took me a long time. Just this spring, I took social media and email off of my phone and thought it wouldn't last, and I wouldn't be able to do it. I did it. I did it. I did it, Russ. And, you know what? My life is infinitely better. And, here we are. And, I think it just--my husband likes talking about the power of simplicity on the other side of complexity. Meaning, like: you've slogged, you've tried, you've struggled, and then you come to a simple solution that wasn't possible before because you still had too many loose threads that you had to kind of work out. So, it took me about a decade to find this balance. Yeah, I think you're right. I think that we will get there, because we're having more of an open conversation where researchers are looking at the costs, and we're asking ourselves what really we have always asked ourselves, which is, let's make sure that we use technology and it does not use us. |

| 24:14 | Russ Roberts: So, let's go to the topic of conversation. You did a remarkable thing in February of 2016: You, for three days, logged all of your conversations. Tell us what that meant. What do you mean by--what did you actually do? How much detail and what was the point of that, and what did you learn? Monica Guzman: I had a chart. I walked around with this chart, and every single exchange that I had--not digitally, it was only the in-person ones--every single exchange that I had, I marked and coded in a bunch of different ways, like the duration of the exchange, whether it was--who it was with. I captured certain things: I think the start and the stop of every single conversation I had for three days. It was exhausting. And, then at the end, I used it to ask myself questions about what do longer conversations make possible? What's happening with shorter conversations? What's happening with the relationship of the people engaging in those exchanges? It was absolutely fascinating, and I was just so curious to test, or just to observe myself. When do those exchanges happen? I mean, I wrote down even the 'Hello,' 'Hello' to somebody just passing by. I wrote down everything. And, it was really cool to see how many longer conversations I was having--20 minutes or longer. They're fairly rare in our lives. They really are. And, what came out of that, right? And, it helped me realize that what comes out of conversations is so much more than the logical content of what you're talking about. We're not just robots teaching each other, informing each other. We're connecting. We're building bonds, we're building trust. We're feeling good. We're enjoying ourselves. And so, I rated it on enjoyment. I rated it on how much it seemed to have strengthened a relationship among the people engaging in the conversation. Things like that. And, oh man--and it's been sort of a lifelong--it goes back for me, this obsession with conversation. It is such a sophisticated, extraordinary skill that we all have, and we don't really stop and appreciate that, all the little micro-decisions that we make based on someone's gesture, how they respond, whether they're sitting there silent, who knows, right? We're trying to exchange meaning; and it's an amazing thing that we know how to do. And, it's made it so much possible, but it can also destroy us when we don't use it, when we limit our tool set. Anyway, so conversation is an extraordinarily powerful medium. It's the most powerful platform there is. Russ Roberts: Do you ever think how strange it is that we don't--at least I didn't, and I don't know anyone who does--teach their children how to have a conversation? It's this amazing tool we have. It's a tool that we develop through experience, but very little self-reflection and almost no instruction. Your book is an attempt to provide that instruction, and it's full of practical suggestions. But, don't you think that's bizarre? Monica Guzman: It is. It is. And, honestly, I think one of the only reasons we're even talking about conversation is because technology came around and sort of splintered it into all these little pieces. And, we're sort of seeing the consequences of conversation being splintered and engaging a conversation in places where it wasn't really designed. We didn't evolve to do this. And so, now we're going back to the roots, and going, 'Wait, what even is this?' And, 'What do we lose when we're changing the ways we can have it, changing the ways we can engage?' But, yeah, we don't--I don't think that we teach each other how to do it, because we haven't had to. I just don't think we've had to. And, we have evolved instinctively so many sophisticated ways to read and have radar on at conversations, to work on the emotional level and the informative level and the safety level of our own security when we're in a conversation and persuasion and debate--and, like, all those things seem to be so automatic, and we haven't had to stop and dismantle them and dissect them and see how it all works and comes together. Russ Roberts: If I had to give one piece of advice about conversation or one instruction, or--something I write about in my book, Wild Problems--I would say--and this is almost impossible advice to take, by the way, so, I don't give it with a grain of salt. I give it with the understanding that it may not be that useful. But, the advice I would give is: when you go into a conversation, do not think about what you're going to get out of it. And, I think so often we go into conversations-- Monica Guzman: I love that-- Russ Roberts: either implicitly or explicitly, saying, 'How can I get the most out of this conversation for me?' Rather than, 'Let's produce something together, and I don't know what it'll be exactly and I'm excited to see where it might go.' And, 'I have to make room for you,' because otherwise it's a monologue. Monica Guzman: Oh, exactly. And, there's so many things that are getting in the way of how we allow space for the unpredictability of conversation, including how many of our conversations now are on Zoom? How many people are working remotely? When you work remotely, you get together on a Zoom, right? And you have to have an agenda to structure how you move through things. And so, you get accustomed to agendas, to predictability. And, on Zoom, it's impossible to just turn to the person next to you and go, 'Hey, I love the earrings you're wearing today.' 'What's up?' And, to make those little connections. You're always in plenary. And so, the way it limits those moments of spontaneous interaction are pretty incredible. But, yeah, we're finding ourselves in this place where we're so busy, we've got so much going on, we're on our phones, we've got a lot to do. And so, the actual time that we could spend on loose conversation, it just feels like we have to make it useful and effective and productive, and that kind of kills some of its spirit. So, I mean, I'd be curious if people actually polled themselves. Like: How many conversations longer than 20 minutes, not digital, do you have in your day? |

| 30:31 | Russ Roberts: Of course, some of those aren't good. They're bad conversations. They could be, 'I can't believe it. I couldn't get a word in.' Or vice versa: 'Boy, what was I thinking? I just talked about myself the whole time. I was terrible.' And, you leave that conversation empty and feeling that you missed an opportunity. Living in Israel--people linger over meals longer here than they do in the United States, in my experience. Might not be accurate, but that's my assessment. And, it's not uncommon for people to have a two-hour meal, which is, I think, somewhat uncommon in the United States on average. And, if you go into a meal with a friend without an agenda and you let it go where it can go, it can be exhilarating. And, there really is nothing like it. It's a remarkable thing. And, as you point out--I think it's a tremendous observation--it's usually not, 'Wow, I learned so much,' or, 'Wow, I was so clever,' or, 'Oh, I want to remember that joke or that story.' It's more just: What a great experience with another human being. And, we often don't think about that. It's such a powerful and important thing that you discuss in your book along those lines. And, I think it's underappreciated. Monica Guzman: Yeah. And you know, one of the things that I've also have really come around to as being such a gift of conversation, of that kind of conversation, is our ability to discover ourselves. We're always having a conversation as a conversation with ourselves. We're judging ourselves. We're saying, 'Ah, you should have done this.' Or, 'Go, hurry up, do that.' There's a dialogue within us. And for us to be able to--in fact, just last night, I had a couple of very good friends over, and over wine and dinner we sort of nourished our bodies, and suddenly, like, stuff comes out. Right? We ended up having an extraordinarily deep, profound conversation about life, death, and then friendship. And, there's a dialogue I've been having with myself--excuse me--about our friendship. And, then I felt like I could just bring a little bit of that dialogue in, to sort of test it with them and see what they would say. And, based on what they said, I ended up kind of reframing some of the stuff I was thinking of, and it's sort of changed our relationship for the better. And, it's so cool. It's so cool. And, it's not like--that wasn't an agenda. I don't know what we were going to talk about. But it was that feeling safe enough to share something that's in your head that can just swirl around and get some feedback, and trusting that the other people would know where you're coming from and wouldn't misunderstand you, and that you're connected enough that you can say with your words, but also with your giggles and your gestures, what you mean--was just magical. And, I think that the book--my book talks a lot about curiosity, and I've thought a lot about how curiosity is a form of caring. It's a gift. How many times have you been--you're suddenly with a group of friends or people who know you or coworkers or whatever, and you have something you need to do, but maybe there's something that just happened to you, makes you feel good, and may be cool to share, but now's not the time. We got to get down to business. And, then when one of them goes, 'Hey, how was your day?' And, you kind of release a little hint about that, 'Well, this cool thing happened, but let's just get to work.' And, they go, 'No, no. Tell me what happened.' You tell them what happened and they go, 'Wow, tell me more. How did you feel? That was amazing.' And, it's that, 'Oh my gosh, they want to listen to me. They see me. They want to know what's up. They're curious about me.' I think a lot of our discussions online, especially around politics, are about the ideas. When we focus on the ideas that's the center of gravity, instead of focusing on each other and our journey through this world and how we interpret world events and how they mix in with our values and experiences and who we become as people and our ideas about how we should all thrive together. That's a fascinating thing. But, we usually get stuck just talking about the idea and not getting curious about the person, which can just brighten and open, invisibly, this space that we can fill with the most profound things. Russ Roberts: I've never thought about this, but when I think of the word 'empathy,' and if you and I were having this conversation face-to-face, and we were having it in a coffee shop, and you came in and I saw tension or anxiety on your face, the empathy that I normally think of in that kind of setting is: I want to show Monica that I've noticed that she's not 100%--assuming we knew each other. It'd be hard to recognize it in a new friend, perhaps. But, that's what empathy is. Empathy--in my mind--empathy is: I want to show you by my face in response to your situation that I'm aware of what you're dealing with and I'm empathetic. I feel bad for you. And, if you told me and you blurted out, 'Oh yeah, I had this issue at work or with a friend or a coworker,' and I go, 'Oh, that's too bad.' And, that's empathy, in my mind. But you really raise a deeper, more powerful form of empathy, which is curiosity. We don't usually--I don't, anyway--think of them as related, but they are. It's not just, 'Oh, what's wrong?' And then you tell me, and I make the face of empathy. It's rather: I actually have real curiosity, not feigned emotional support--or real even, if I care about you--but just showing that. It's more than that. It's trying to understand what you're dealing with, going through, struggling with. I don't think of those two as related, but you're suggesting they are, and I think it's very beautiful. Monica Guzman: I think you're absolutely right. And, what a way to give support. Right? That conversation we always have with ourselves can get pretty toxic. And, if somebody actually shows enough interest that we could explore it with them and we trust them not to mishandle it, it's awesome. It's awesome. We learn about ourselves. And, what a gift to give each other. |

| 36:57 | Russ Roberts: You're right. Something I believe deeply and is so hard. Before, I gave my advice about conversation, meaning: Don't try to maximize the value from it or don't have an agenda about what you're going to get out of it-- Monica Guzman: I love that-- Russ Roberts: And, I mentioned in passing, it's really hard advice to take, because I think we're very hardwired to think of ourselves first. And, similarly, you say something I think incredibly profound that's really hard to take to heart, which is: Good listening is not silent waiting. Explain that and maybe give us some idea of how we might actually remember that. Monica Guzman: Yeah. Yeah. Right. I mean, so much of the time, especially in disagreement, we have a point to make and we want that point validated and we want to win. And, there's just so many layers of objectives that get in the way of real connection and trust-building that could actually get us somewhere. But, I talk about how listening--it's more than paying attention, being present, making sure you're not just waiting for your turn to speak. Listening is showing people they matter. That's what it is. That's the criteria we each have: Have I been heard? Do I feel like I mattered in that? Do I feel demeaned, neglected, ignored, shoved aside in one way, undervalued? And the thing is, we all matter. And I think when we lose sight of that, we just lose sight of ourselves. I mean, we start to just kind of stray. And, going back to that thing about: anytime you're in a disagreement, even online, looking at what the other side is saying and you go, 'Ugh! They're crazy, they're stupid, they're evil,' you're wrong. You're wrong. That's it. You're wrong. You can be pretty sure of that: that it does not come down to that. And, if you believe that it does, you are already condescending--when you look at that sign, you are approaching it with condescension and you can't be curious. And, that kind of shuts down everything before it starts. If you come in knowing that, thinking that that is the case, now you're going to come into conversation and prove it. You're going to prove to them how crazy they are. Good luck with that. And, we're not really set up to accept that about ourselves, right? Even if it were true--which it almost never, I mean, ever is, right? Very few cases. So, I think we have to get out of the mania of believing those kinds of untruths, and asking ourselves instead: What am I missing? If it seems crazy to me, then I don't have access to the reasons that make it sensible to them. So, let me go figure out what those reasons are. Let me open things up a bit. Being a journalist, I get discouraged because so much opinion-journalism uses those things. Headlines that say this or that thing is crazy, this or that person is crazy. I'm like, 'Ah!' We're remodeling these judgments for each other; and it's just really cool, but it's always wrong. It's always wrong. Everybody has their reasons. |

| 40:01 | Russ Roberts: The other thing I would just add, and again, it's so hard to remember this in the heat of a conversational moment, is: if I'm not actually listening but waiting to talk, I'm objectifying you. I'm using you as a tool for my own self-expression. And, of course, I want to make you laugh or I might want to impress you. I might want to earn your respect. So, a lot, sometimes, of our speech is purposive in that way. But, you're suggesting there's a different purpose, which is just noticing the other person and treating them with deep respect, the same respect you'd want to receive from someone else. And, if we objectify people that way as tools for our own self-expression or self-confidence, we've missed a tremendous human opportunity. Monica Guzman: Yeah. And, we're just working on our own projection again. And here we are, have access to another person, a source of external truth, and we're not wondering about it. We're not going to figure out what that actually is. It makes me think of what folks on Twitter did to you with your Elon Musk tweet, right? Imagine if all those people had said, 'Do you mean this or this, Russ? Question of clarification.' I work at Braver Angels, which is an amazing large nonprofit working on depolarizing America. And, in our own culture, internally, somebody proposes something and then we leave the space open for questions of clarification. So, before people give comments, that's what we do. 'Wait, what did you mean?' And so, we each kind of query our own way that we heard what was said, and then if there's something where we're like, 'What???' that's when we ask. And, the way that clears things up--right?--and it models, 'We're trying to get you right before we use what you say.' Before we dissect and judge it, let's make sure we know what you mean. And so, imagine, like, the revolution, if people on social media ask questions of clarification before jumping on any reaction to what is being said. Russ Roberts: Actually, that Steve Jobs poll, somebody tweeted back at me how I was doing--for the thousandth time, I was indulging in technological determinism. And I thought, 'I don't know what that is, but evidently I do it a lot, which is a little bit alarming.' And, I simply wrote back, 'I don't know what that is. Can you explain?' And, a wonderful moment on Twitter--and there are many; by the way, I'm a big fan of Twitter, when it's done well--he wrote back, 'Are you serious?' And, he meant it as an actual question. He said something like, 'Are you serious? I mean that. You really don't know what it is?' And, I said, 'No, I don't.' And, I didn't feel like using Google--obviously I could have found out. But this person was accusing me of something that was a real habit, in his mind, of my discourse. And we had a clarification moment. And, I said, 'No, I am serious. I don't know what it is.' And, he explained what it was and other people chimed in. We had an actual conversation on Twitter. And it was a rare moment. Monica Guzman: That's great. My friend Angel Eduardo talks about how social media is the boss level of discourse--gamer speak--and it really is. It's not that great conversations can't happen on social media. It's that all the ways that we communicate good will when we do have our full toolbox of communication at hand--you know, gestures and giggles and tone and everything--you have to translate that into words somehow or over time. The fact that he could say, 'Are you serious?' And, you didn't read it as an affront, right? Because that's we--on social media, we tend to read things in sort of a mean voice, even if it wasn't spoken that way. So, to get past that, you need to build a bit of a connection or you need to use your words, 'No, I really mean it. I don't mean that in a mean way.' Things we wouldn't normally have to say, because you can see the smile on my face. You can tell, I mean you no harm. You can tell I'm not trying to use what you say. I'm just trying to understand you. |

| 44:19 | Russ Roberts: Talk about your bus trip, which is a big part of the book we haven't got to yet. You took a group of people in Seattle--which tends to vote very much in a blue way ['blue' meaning politically pro-Democrat, vs. 'red' meaning pro-Republican--Econlib Ed.]--to Oregon to a county where it was the polar opposite. It was a red county. Why did you do that? It was a crazy idea. And, how did it turn out? Monica Guzman: We did it because the Seattle-based newsletter that me and my co-founder started was all about being curious and honest, bold and inclusive. We had all these values. And then the 2016 presidential election happened; the city felt dead the next morning, just dead. Because we want to be curious, we wanted to help people understand; but man, Seattle's full of blue people and even the red people don't tend to speak up much. They're not terribly welcome. And so, we got notes from readers going, 'I want to be curious, but I don't know how. I don't know anyone, or they're really far away. There's still these lifestyles I don't understand.' So, we ended up stumbling on this interactive map that showed--if you plugged in your county anywhere in the United States, it would show you the nearest county geographically to yours that voted exactly opposite in the Presidential election. So, you plugged in King County, Washington where Seattle is, and you get Sherman County, Oregon, this county of 2000 people on the Columbia River, North part of the state, all agriculture, lots of wheat farming. So, me and my co-founder were like, 'Could we--what could we do?' So, we asked our readers, 'If we were to figure out a way to connect these worlds, would you all be down?' And, a bunch of people said, 'Yes. Oh my gosh, it'd be amazing.' So, one thing led to another, met some incredible people down in Sherman County. Googled, found this woman who has been covering the community in a small blog for years and years; she's in her eighties. She connected us with someone who is now a dear friend, Sandy McNabb, an agricultural agent in the county. And, we partnered to create this experience. Ended up taking a five-hour bus ride down, the 19 people from King County who signed up. We met about 16 people in the little tiny town of Morrow, population, I don't know, like, less than 300. And, we had a lot of conversations that were not about politics. Before we got to the politics, we did a tour--a bus tour of the wheat farms. We shared a meal: they had donated a meal. And, one of the most powerful moments was when a farmer named Darren Paget stood up and pointed to the leftover sandwiches on everyone's plate and said, 'If you knew what it took to get that sandwich on your plate.' Just looking at everyone in the city[?], you could hear a pin drop. No one from Seattle ever goes to Sherman County, but the people of Sherman County have to go to the cities. Their kids live in the cities, they have to go to the city. But, no one goes there. It was--oh my gosh, what we got out of it is too long of a conversation. But, among--I think the thing I'll mention now is one of the most pernicious things we believe is that people who oppose what we support must hate what we love. So, a bunch of folks from King County had ideas in their heads about people who voted for Trump must hate the environment, must hate gay people, must hate--you know, name your thing. And, among the things we learned was there's more variables we didn't consider. Right? That if you're in that frame of mind, there's other things you didn't consider. And, these farmers, many of them brought up this thing we'd never heard of, the Waters of the United States rule. Had you heard of that? Russ Roberts: No. Monica Guzman: I hadn't heard of that. Russ Roberts: No. Monica Guzman: Well, and it's this part of our law that determines when the federal government can kind of claim regulation authority over a body of water. And, for a lot of farmers, if there's a really heavy rain in a valley and suddenly there's a pond where there wasn't one, could the government come in and say, 'Okay, that's our land. We have to regulate that. Bye.' And, it sounds absurd, but there's actually been some really close calls and pretty weird stuff going on in that. So, for a lot of those farmers who just operate at these little margins--I mean, farming independently is a really tough game. They just don't trust Democrats. They absolutely did not trust Democrats to even care about that, but they trusted Republicans and they trusted the businessman that they elected President: nothing to do with social issues at all. And so, on the way back, I talked to people and a lot of them mentioned, 'What is the United States rule? Who knew?' So, that's an example--I think it's a really powerful example of when we don't get close--when we try to solve these mysteries from a distance--we don't see what we're missing. Things that can take us away from this idea, this false idea that people are crazy or evil or stupid, and closer to an idea that they have their own reasons. And, our media is not going to give us those. Right? Sometimes we have to check the reality. We have to go and talk to people ourselves. And, that's one of the things I think is the most important thing we can do for our democracy, is get curious about each other with each other. Not by sitting down on a Sunday and reading a bunch of statistics or some narrative that some expert has created. There's no expert on you and there's no expert on me. I'm the expert on me. Talk to me. Talk to me. Russ Roberts: That's beautiful. There's an idea that if you want to lose weight, tell your friends you're on a diet. So, that kind of way of holding yourself accountable when they put out the cookies and you're eating the fourth one, it gets harder to take the fifth one. That would be the argument. |

| 50:16 | Russ Roberts: Has writing this book put pressure on you to be a better conversationalist and a better listener and a more tolerant political interactor with your parents or with your friends? Or, has it kind of just always been pretty easy for you for a while? Has the book itself forced you to do anything you realized, 'Oh my gosh, I'm the author of this book. I better not,' fill in the blank? Monica Guzman: In public spaces, I sort of feel that pressure. Like, 'Oh, I better display these skills.' But, to add a little complicating nugget to that, I was in North Carolina doing a book talk and meeting with the Braver Angels Alliance there. We have chapters all over the country; it's really great. But, my husband was saying, as we were coming home from the book talk, he said, 'I almost raised a hand, Monica, and asked you a question that would've been pretty challenging.' I was like, 'What?' And, he's like, 'Well, I was going to say, I've been there for a lot of your conversations with your parents.' And, he goes, 'And, you don't do anything of what you tell people to do in your book.' Like, he was exaggerating, right? There's a lot of things we do: We acknowledge each other's good points, etc. But here's the thing: With me and my parents, there is so much trust that we call each other names. We can yell at each other about some of these political issues. We've built up that resilience where we don't have to kind of guard and take careful steps. But, do that with someone with whom you don't have that built up and you don't have that trust and you're just beginning, and it's not going to work. So, a lot of the tactics are about that. But, I think it's important to say that the reason I wrote this book about curiosity--and I think it's important for our political moment--is not because I think we need to talk everything to death or because understanding is the end goal. The end goal is persuasion. The end goal absolutely is persuasion. We need a society where we can mix our ideas generously and the best ideas actually win. We can say, 'I want my ideas to win,' but guess what? You're not a genius. I mean, maybe but I doubt it. I mean, no one person has all these answers. Sorry, I don't care how educated you are, how intelligent you think you are. The best answers have to come out of communion of ideas with each other and presented generously and interacting well. That's the society we want. But, when there's too little trust and too little connecting us across difference, and too little approaching each other to check ourselves and our projections of each other, we can't do that. Persuasion breaks. And, I think that's where we are. We're out there trying to persuade, but we haven't worked to build the trust that's been lost. And so, it's all just making it worse. Right? So, to me, it's less about using these tactics as the end goal: that this is the only way to have conversations. I think we're in a kind of adolescence with our discourse because we've just leveled things up so profoundly with our technology and with our access and everything we're discovering about each other's individual self and identity--and we didn't even talk about that. So, because of all of that, we're kind of back to this adolescence; and it's awkward and we're mad, and everyone feels misunderstood. And, so, we need to work our way through that, so that we can get an even stronger, mightier democracy and society that can thrive and can lead and can be amazing. So, that's it. These tactics are about: let's get there, let's rediscover that or discover it anew, right? Because we're always trying to be a more perfect union. Cool. This is, I think, what it's going to take, this kind of humility. And, I can't wait for the day where we can have around Thanksgiving dinner, the kinds of wild political conversations where it doesn't feel like you're cutting to the bone with every single thing you say, right? Where we've built up that resilience with each other and we know there's love at the foundation and we're learning. Russ Roberts: So, I have to subscribe to your viewpoint. I'm the president of a college that believes in fearless open inquiry, Shalem College in Jerusalem. Typically, our classes are 25 students or fewer and many of them are organized around Great Books--not all of them, but many of them are. So, our students will be reading The Iliad or Ihe Odyssey or Shakespeare or the Quran or the Old Testament or the Talmud or a work of Western history. And, I believe very much, as you just beautifully articulated, that on something that in theory has little emotional baggage--say, what is really happening in The Iliad or what Homer may have meant in The Odyssey, or what the significance of that is for your daily life or one's daily life or the country we live in--those are arguments that, when we have them, knowledge emerges. It isn't taught, the knowledge is not taught. I don't believe--we don't want our professors here lecturing our students about what The Iliad really means, or its significance or The Odyssey or any other text, because that kind of knowledge doesn't--I don't care how much literature they've read about those books or how smart they are, how educated they're, as you said, that's not where wisdom comes from. Wisdom comes from you grappling with the text in the company of other similar people-- Russ Roberts: and wisdom emerges. It is not thrust upon you. When it's thrust upon, you don't remember it and you don't own it. And, when you're allowed to let it emerge, it's real and you own it, and your thinking changes, you're understanding is enhanced. I believe that. But, I didn't believe that I[?] couldn't[?] work here, and I believe that is the idea of our conversation. It's the idea behind what used to be called real education, what used to be real education. And, it should be the idea behind democracy. It only goes back a few thousand years to Plato, etc. And, yet, I would just throw in John Stuart Mill, if you haven't read On Liberty lately, read it, which is about this question of disagreement and how truth and understanding emerges from disagreement. And, yet I think most people don't agree with it, don't believe in that anymore. They obviously don't believe it the way they used to on a college campus. You quote David Smith--it's a great quote--the question which do you value more: the truth or your own beliefs? Most of us, again, hardwired probably, we like our own beliefs a lot more than the truth. And, we don't trust that conversation to create that understanding and wisdom because we're afraid we might find out we're wrong, and that hurts. Monica Guzman: That's right. Russ Roberts: If you get to a point where it doesn't hurt, it delights--because you realize you can learn something. That's really the point of your book. It's really what it comes down to. The book is called, I Never Thought of It That Way. And, that moment of exhilarating awareness is an enormously, extraordinary, beautiful human experience. And, most of us are terrified of it. So-- Monica Guzman: Or we tell ourselves it's not possible. There were some studies recently that showed how much we underestimate the delight of conversations. We keep underestimating that it'll be interesting, that it'll be fun. We just do that over and over again. And I think it's true. We just come in with our own fears. And, right now, as you probably know, a lot of what's holding us back is this idea that engaging with the other side is going to make me a bad person. If I encounter bad people, if I encounter bad ideas, it's like opening a Pandora's Box. I will be infected or I will allow the world to be infected. And so, now that has come above this mandate to learn from each other and to have our opinions be in generous communion with each other. We're going, 'No. There's toxic, poisonous opinions and we got to keep them away from each other.' So, now we're building up walls and we're forgetting--it's exactly what you said: Can we get to a place where we trust each other again? That, we have to build this trust, in the conversation, that ideas don't infect as easily. Bad ideas don't infect as easily as we might think. Looking at bad ideas generously is more about looking at the people who hold them generously. Which, by the way, makes them more intellectually humble. There's been research on this, too, that I'm so into right now: where, if someone just brings to mind a person in their life who tends to receive their ideas generously--not agree with them, but just listen, show them they matter--that person will become more intellectually humble. Meaning, they'll be more likely to let some breathing room appear around their ideas so they could consider others. This is healthy persuasion. But we cannot begin at this place of, 'You're lost. You're evil. If I engage with you, I lose my self.' Like, imagine--I'm a journalist. If that had been true, how many people who have done unsavory things have I talked to and tried to help their communities understand? And, if it were true that my witnessing somebody's story is a bad thing or makes me a bad person, imagine everything we wouldn't know about each other. We've got to get past this. |

| 59:53 | Russ Roberts: Well, you have a nice mantra toward the end of your book, which I like to think is my mantra. It's nice to see it expressed so succinctly. It's three words: Honesty, curiosity, respect. I would add humility, which you would, too, if you had a longer--it's a sign you carried. So, if you had a bigger sign, you probably would've added humility. Russ Roberts: But, each piece of that is so important. And, the respect part, I think, is often the hardest part for us in those interactions, given the current climate of the dopamine we want from our followers on social media and so on. But, it's everything. It really is everything. Monica Guzman: It really is, really, really is. I mean, we think of respect as, like, 'Well, if I don't respect that idea, so I can't possibly respect the person enough to listen to them. I can't make them think they matter, because then they'll think that I validate their idea, and what will people say about me? Will I actually create new harm in the world?' And, by the way, it's worth saying: These insecurities are very understandable. The adolescence we're going through now is not just about technology and communications-platforms. It's about the norms that are being shaken up. It's about the new knowledge that is coming in. It's about more things being put into tension that we're just not used to, while the world is going through all kinds of crises. It's shaking--it really is shaking our faith in all kinds of things. All kinds of things that we used to just take for granted. And so, that's tough. That's going to be hard. We're going to get scared. We're going to wonder if we need to just do something different, and we're going to wonder if this idea, this democratic ideal of conversation and open mindedness, maybe that's wrong. Like, I think some people are honestly in that space, and not because they don't like everything that's given us, but because they're afraid it's leading us somewhere dark if we're not more vigilant. What does more vigilance mean? And, to me, more vigilance is: it's not leaning away. It's leaning in even further. Right to the thing that scares you most. And, I know that sounds counterintuitive, but I don't see another way out. Russ Roberts: It's easy to forget that the other side is as self-righteous as you are, and if they have all the authority, that world's going to be just as bad as the one you think you're in now, and actually a lot worse. So, monopoly for the right side is really bad. It's democracy and competition among ideas that creates good outcomes. And, it's hard to trust that process, right? And, I think one of the challenges of democracy in the United States right now is the loss of trust that the other side will play fairly. And, therefore, when you're in power, you have to do everything you can to get your side as far ahead so that when they come in, they won't catch up. And, that's a lack of respect, obviously. And that could turn out, well, really going to turn out very dark--it's going to be a very dark outcome, in my view. |

| 1:03:04 | Russ Roberts: Let's close with the reaction your book has received, if you can share it. You live in Seattle. We've talked about Seattle has a certain, on average, mindset and perspective on the political policy space. Are people--do they like your book or is it too much both-sidesism for a lot of people? That you are respectful of the other side, that you do imagine that you could be wrong. Talking to me, it's like, 'Yeah, go, go. That's right. Yeah.' But, I think probably a lot of people will find that, not just they don't agree with it, they find it offensive. Are you getting any of that reaction? Monica Guzman: Yeah, I am getting some of that reaction. And, honestly, that's the thing I'm most curious about right now. I'm finding myself obsessed with that reaction. So, for example, I saw a review from a woman who said, 'Well, she wrote this book, I guess before Roe v. Wade was overturned, which makes sense because there's no way that she would support engaging with the other side when the other side doesn't support your humanity, doesn't support your rights. Clearly, that's a step too far. She didn't address that. So, and if she had, she would've agreed with me that that's a big fat red line. And, as soon as we can say that they don't respect our humanity, clearly the only way to maintain our dignity and self-respect is to not engage.' But, that's not what I would say, at all, but that is one of the criticisms. I anticipated a lot more of this type of reaction of--you know, she's an apologist. She just wants us to come to the middle. She wants us to moderate our views. Not at all. Not at all. We need open-mindedness all across the spectrum, you all. It's no good for us just in the middle. That's silly. But, I understand where this comes from. The most encouraging thing to me-- honestly, I thought this was going to be a lot louder than it is--is I've been on conservative podcasts. I went on Glenn Beck. It was fascinating conversation with Glenn. I've been on liberal podcasts; I've been on libertarian podcasts. I mean, these are partisan groups who feel at war, but see that this is important. See that the ideas here are important. See that there have to be ways that individual people take up the reins here. That we don't just wait for politicians to figure it out or media to figure it out. I think a lot of people are in that place, and that's just not going to be useful. The other barrier that I get, too, is I remember I was on this very, very liberal podcast, this group, the Daily KOs' podcast, progressives online. And, there was this tension building up and a lot of, you know, just kind of scrunched faces. And, finally I said, 'You don't have to talk to a Nazi tomorrow.' And, there was this just tension-relieving laughter. 'Oh, thank God. Doesn't want us to talk to a Nazi tomorrow.' No. But, I think when we come into things so afraid, we tend to think of the absolute strawmanning. We think of the worst possible thing; and we argue from there: 'You want me to talk to the devil. That's what you want? Let me tell you all the ways that's terrible.' Right? But, we can't begin there. We can't begin there. There's no way. You make--to quote John Powell, there's a pastor who came to--brilliant man named John Powell at the Othering & Belonging Institute who said, 'John, are you asking me to bridge with the devil?' And, John said, 'Maybe don't start there. Don't start with the devil. Do the shorter bridges. Do the smaller bridges.' And, then he says, 'And, after a while of doing those shorter bridges, you may ask yourself who you're calling the devil.' And, that's what I think it is. Of course, we have these monsters in our heads and we're afraid. And, it may seem like that's what I want you to do. I want you to put yourself in the presence of a monster and be hurt. Why would anyone want that? And, it's also worth saying: Each of us absolutely has our own calculation. Nobody can tell you or force you to be in a conversation you're not ready for, you don't feel comfortable in. There's plenty of political disagreements that amount to a rejection of your own identity. I get that. I feel that. That's a lot harder. And, that's on you. But, you don't have to go to that. Talk to your friend who agrees with you on everything but one thing and have the conversation about that. Or, don't even have a conversation with a person. Have the conversation with yourself, get more curious. The next time that you read an article that is all about a perspective on the other side of yours, ask yourself as you read it, what is the deep down, honest concern that this person is trying to communicate? Make sure that you don't vilify that person as you read them. Listen to them generously. Even that will make a difference. So, these are small steps. There's not: Talk to a Nazi tomorrow. No one's got to do that. We're good. |

| 1:08:20 | Russ Roberts: I think in your trip to Oregon, if I remember correctly, you started off with people talking about their families. What was the opening conversation about? Do you remember? Monica Guzman: Your favorite childhood memory? Russ Roberts: That's what it was-- Monica Guzman: We had people talk to each other about your favorite childhood memory so that they humanized each other before they got into opinion versus opinion. Russ Roberts: And, I don't think the Devil has one. So, if you are in the presence of the Devil and you try that and they can't come up with a childhood memory, then you know you probably should back away. But, in most other human situations--you know, everybody had a mom, or had a bad one--had a childhood trauma, which would be the other way to go. What's your least favorite moment as a child? We all have wonderful and challenging memories of our childhood. Not me, actually: my mom--I have no challenging ones. My mom is and was a saint when I was young, so I don't have anything negative to say about my mom. But, if it's the Devil, then you're probably--like you say: Back away. Start somewhere else. But, most human beings have a childhood memory. Monica Guzman: Exactly, exactly. Dare to approach and you might be pretty surprised what you'll find. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Monica Guzman. Her book is, I Never Thought of It That Way. Monica, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Monica Guzman: Thank you so much, Russ. This has been fun. |

In our highly polarized times, everyone seems obsessed with the truth: what is it, who has it, and which side's got it all wrong. What we don't seem to care about, says journalist Monica Guzman, is the truth behind perspectives other than our own. Listen as Guzman and host Russ Roberts discuss Guzman's book I Never Thought of It That Way, a call to get interested in the people behind the positions, and the experiences, hopes, and fears that lead to their beliefs. Guzman and Roberts also discuss the role of great questions in sparking meaningful conversations, and how we can not only get along with, but even learn from, those with whom we ardently disagree.

In our highly polarized times, everyone seems obsessed with the truth: what is it, who has it, and which side's got it all wrong. What we don't seem to care about, says journalist Monica Guzman, is the truth behind perspectives other than our own. Listen as Guzman and host Russ Roberts discuss Guzman's book I Never Thought of It That Way, a call to get interested in the people behind the positions, and the experiences, hopes, and fears that lead to their beliefs. Guzman and Roberts also discuss the role of great questions in sparking meaningful conversations, and how we can not only get along with, but even learn from, those with whom we ardently disagree.

READER COMMENTS

Doug Iliff

Dec 12 2022 at 9:05pm

I had to laugh when the subject of evolving norms came up, with the projection that middle school students should be banned from possessing cell phones. At dinner my wife, an all-star choir director with regional and national awards in private, public, and homeschool competitions over the last three decades, was marveling at her experience today with homeschool kids in fourth through ninth grades.

“I ask them to mark a measure in pencil, and they just look at me!” She has to get in their face, individually, to get them to snap out of their spell.

But it’s not just the kids. Parents are just as bad. They ignore, or do not comprehend, basic email instructions. It is clear that we are creating a race of hyper-social intellectual morons. We need those norms to evolve sooner, not later.

Shalom Freedman

Dec 13 2022 at 8:27am

Toward the end of the conversation Russ Roberts and Monica Guzman make a kind of joke about someone challenging her argument for greater openness, respect, and honesty in listening to the ‘other’ by using a ‘strawman’ the ‘Nazi’ as example of the other. In this the feeling seems to be that almost all people are decent and will reveal themselves to be if they are heard with understanding. She suggests most people are ‘mysteries’ whose views are far richer nuanced and reasonable than we initially assume by our simplistically categorizing them upon encountering them.

My own less sanguine view is that there is a lot more stupidity craziness and evil out there than these two very smart considerate curious and caring people want to acknowledge. Russ in one sense acknowledges this by his mentioning earlier in the conversation the responses he received by tweeting something somewhat favorable about Elon Musk. But he does not point out any of the present obvious examples including to my mind the most conspicuous political one for anyone living in Israel the willingness of a great share of the world’s people including a great share of its intellectual elite to believe that the Jewish people have no historical connection whatsoever with the land of Israel and the city of Jerusalem. The willingness of so many people to believe historical untruths is of course just one example of the of the willful prejudice characterizing not only individuals but whole communities and societies.

Ben Riechers

Dec 13 2022 at 10:39am

I suspect that most people who lean conservative are desperate to be heard. Yet they cannot speak out, even ask questions it seems, without putting their financial security or their close relationships at risk. People are so afraid to speak that it sometimes takes a chance comment for me to learn that a person I have known for a while has similar concerns.

The WSJ recently published Barton Swaim’s commentary, “Why the ‘Smart’ Party Never Learns.” I believe his perspective is one that adds to the conversation. He suggests the ‘bubble’ metaphor, which infers that the people on the right get all their news from Fox and social media doesn’t hold up to even modest scrutiny. An oversimplification of his commentary is something like this. Conservatives cannot escape the views of Progressives and Liberals. Those views are everywhere: TV, movies, colleges, media, at work, and now even in sports.

I found today’s interview delightful to listen to. I have a lot of informal facilitator experience and love thoughtful conversations (I had a 2-hour lunch in the middle of this podcast.) However, it is difficult to find liberals, or people who at least consider themselves liberals, willing to engage. Maybe I’m not looking hard enough.

Susan Rico

Dec 13 2022 at 12:09pm

If you look to Braver Angels (the org that Monica Guzman represents), you’ll find thousands of liberals ready & willing to engage openly & respectfully.

stuart

Dec 14 2022 at 3:25pm

“And, interestingly, I think all those books that I’ve read and interviewed people about are written by liberals, but yours is the most–maybe the only one–that is fair to conservatives.”

Unless one does not consider Haidt a liberal, I’d have to argue he is a liberal who writes books very fair to conservatives. Personally, I see Haidt as a respectful and eyes-open liberal (who has never voted for a Republican) even though he says he’s moved to the middle.

Virgil Banowetz

Jan 2 2023 at 4:58pm

Re: “You don’t have to talk to a Nazi tomorrow.’

How about a constructive conversation with a KKK member? Daryl Davis deserves to be mentioned along this line as a superb conversationalist for extreme cases such as these. He does it extremely well and should inspire all to learn skills for better conversations. Those who think it cannot be done are like the Pharisees complaining that Jesus eats and works with sinners.

https://www.npr.org/2017/08/20/544861933/how-one-man-convinced-200-ku-klux-klan-members-to-give-up-their-robes

Comments are closed.