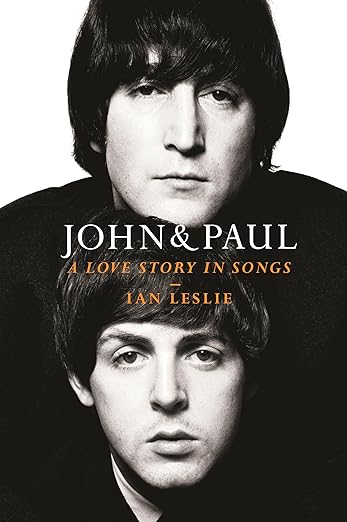

| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: March 11, 2025.] Russ Roberts: Today is March 11th, 2025, and my guest is author Ian Leslie. His substack is The Ruffian. This is Ian's fourth appearance on EconTalk. He was last here in January of 2023, talking about being human in the age of AI [artificial intelligence]. His latest book and the subject of today's conversation is John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs. Ian, welcome back to EconTalk. Ian Leslie: Hi, Russ. It is great to be back. |

| 1:04 | Russ Roberts: Now, this is an extraordinary book. I want listeners and you, Ian, to know a little bit about what I bring when I read this book, what I brought to the book. I have to say, I don't read books like this. I'm not a fan of the Beatles--of John Lennon and Paul McCartney--in the usual sense of the word, a 'fan.' I've never read a book on the Beatles; I never expected to. And, I invited you to EconTalk because you wrote an extraordinary essay, which we will link to, "64 Reasons To Celebrate Paul McCartney: After all these years, he's still underrated." It's an incredible essay. It's 10,000 words--that's about 40 pages. I gobbled it up, and because of that essay, you got a contract to write this book, John & Paul, and because of that essay I wanted to interview you about John and Paul. So, I started to read the book to prepare for our conversation, and I couldn't put it down. I'm not going to praise it any more explicitly. I'm just telling listeners, if you like the Beatles or music or you're interested in friendship or the cost of fame or popular culture, read this book. My wife is sick of hearing me tell people that they have to read it. So, that's the end of my ad, which is rare. I don't generally like books as much as this, so I'm done with the praise. Congratulations. Ian Leslie: That's amazing to hear. I love to hear it. Thank you so much. It means a lot. Russ Roberts: So, let's get started. This is not the first book on the Beatles. I said I've never read one, but I think there've probably been a few. So, talk about your own relationship to the band and their music, how you did the research behind the book. The narrative you produced is relentlessly paced. I couldn't put it down, as I said; and it's told very beautifully. How did you stay on track with that narrative, given the incredible amount of material there is to review, read, listen, watch, and decide on what you're going to keep and reject? Ian Leslie: Ooh, yes. Well, these are big questions. I think your first question was my relationship to the band. Yeah, I mean, I have been a Beatles fan for most of my life. I think I got into them when I was seven or eight. I was a sort of Gen X [Generation X] Beatles fan. My parents had Beatles LPs [Long Playing vinyl records] lying around the house--like most households in Britain at the time, and probably America, too. And so, I've always loved them. And then, I think really in the 1980s, I started reading about them, too, and became absolutely fascinated by the story as well as the music. And, although I've always been into them and always fascinated by them, I never thought I would write a book about them until I wrote that essay on my substack about McCartney, and it went sort of unexpectedly viral. I honestly didn't think anyone was going to read--not many people were going to read a 10,000 word essay about why Paul McCartney is good at music. But apparently they did. And, there was a very kind of emotional response to it, a very big response in every way. And, that made me think, 'Oh gosh, well, maybe I could do a book about this group that I've loved since I was very young.' And the thing that I immediately knew I wanted to do--I didn't want to just write a book of the blog post. I knew while I was writing it that if I ever do do a book, it'll be about John and Paul. I left out quite a lot of stuff about the relationship, out of that essay. Otherwise, it would have been even more ridiculously long. So, I had this idea: I'm fascinated by their relationship, by the chemistry between these two intense, brilliant, incredibly gifted young men. It's so complex and so interesting, and it struck me that nobody has written a book about it, which is sort of extraordinary when you think about it. There's well over a thousand books about the Beatles. There are group biographies, there are biographies of each individual member, and there are lots of different ways to slice the story. There are books about Hamburg. There are books about the drugs that they took; and so on and so forth. But, nobody's just said, 'Look, the nucleus of this band and this creative explosion is the chemistry between these two men. So, what's going on there?' And, I hadn't really seen the relationship analyzed with any really real depth or emotional intelligence at length. And so, it was kind of a big wide open goal. It happened to coincide with something that I'm inexhaustibly interested in. And then, your question: how did I focus the narrative? Well, I pretty much immediately realized that if I was going to tell this story, I had to tell it through the music and through the songs. The subtitle is A Love Story in Songs. We tell the story chronologically from when they meet in 1957 to when John dies in 1980. So, we tell the story of the Beatles and beyond, and we do it through the song. So, each chapter starts with--it is sort of anchored in a song that was meaningful to both of them. And, the reason that was essential is that you can't really understand John and Paul without understanding the music, because they thought and they felt, and they communicated and expressed themselves through music. And equally, you can't understand the music without understanding of the relationship. So much that is vital and innovative, and radical and moving about the music is rooted in the relationship between these two guys. Russ Roberts: And, when you start the book and you see that each chapter has a title that's a song you sort of assume--incorrectly--that, 'Oh, this will be the most famous,'--you'll be analyzing; the most famous songs that the Beatles wrote are the best songs in your view. And, what's beautiful about the book is that many of the songs used are fairly obscure. Not all of them, of course: many of them are famous. But they're not the most famous. And, the reason is that the interaction between these two people that, given how many songs they wrote together, allows you to understand what was going on in their friendship and in their relationship. So, I thought that was--it's really quite extraordinary. Ian Leslie: Yeah. And, if you think about just the songwriting relationship, they get together and they start writing songs when they're teenagers. This was not a common thing to do at the time. The Beatles, by biography scholar--probably the kind of foremost sort of scholar the Beatles, if you like--Mark Lewisohn has said that according to his research, very few other teenagers were doing this anywhere in Britain. Even if they were into rock and roll in the 1950s, actually writing your songs, that was just not a done thing. That wasn't something that people--but somehow these guys decided that's what they wanted to do. And, you can see how the emotional lives of these two then becomes intertwined with their creativity, because, you know, showing other people your ideas is a very exposing thing to do, right? No matter what field you work in, say, 'Here's this thing. Here's this poem I've written,' or 'Here's this tune that I've written.' And, of course, pop songs are full of emotion. They're full of yearning and desire, and jealousy, and all sorts of things. And so, they're kind of communicating on an emotional level, face-to-face over guitars, from the teenage years, from this emotionally kind of formative stage onwards. And, they form this really incredibly strong bond, which is then enhanced and strengthened and sort of transformed in all sorts of ways by the fact that they both suffer bereavements. They both lose their mother during these years, which brings them even closer together. They don't necessarily talk about it very much, but they absolutely know the other guy understands something of the pain that they've been going through. And, it also reinforces their sense of themselves as special. It's different from their peers. They're just not like the other people around them. And, I think the third thing it does for them, it gives them this tremendous sense of agency of determination to make the most of the time that they have available to them, and a conviction that the world that we are living in could just change at any minute, and we can create the world as well as just passively experience it. |

| 10:24 | Russ Roberts: There's a standard view of the Beatles and of John and Paul's relative talent and importance to the band. The standard view is basically that Lennon was the more creative one, the more talented one, the real force behind the band. Talk about how that came to be the standard story in the aftermath, especially of the breakup, and then in the aftermath of John's murder, and why it's wrong. What's missing there? Because, this book really is a revisionist history of the most important band of the 20th century. And, talk about what you were trying to achieve there without--with, using fewer than 10,000 words--if that's okay? Ian Leslie: So, I think you characterize the book very well there. And, it's not revisionist for the sake of it. I just think that we have got it wrong because we had this story--which is formed really, as you say, in the wake of the breakup when, by a generation of music critics, kind of the Rolling Stone generation--who really revered John Lennon. And, Lennon really conformed to their idea of what a genius is, you know: difficult, conflicted, terrible in some ways, messed up. And, Lennon was also this incredibly brilliant, compelling spokesperson for himself--right?. Did loads of interviews around this time. And he was just rude about everyone, and he was nevertheless incredibly compelling. So, he kind of spins this narrative, and they buy it. And, the narrative is, essentially, 'I was the creative genius and motivating force behind this band. I had a fairly talented sidekick in Paul McCartney. I respect him as a songwriter. But, Paul was always trying to--he was the commercial one. He was the one with the pretty tunes and the pretty face. But, I was the two artists. And I had to break free of the Beatles in order to really express my inner kind of artistic urges.' Now, this is just all wrong. I mean, it's not all wrong. I mean, he was--Lennon really was a genius, but was at least one half of the creative genius. But, McCartney was a genius, too. He was just as innovative in some ways, more so. He was always pushing at the boundaries of what was possible musically speaking. And, he was also kind of the engine of the band: particularly towards the latter years, he was the one driving it forward. But, this narrative got set because Lennon fitted that idea, and because McCartney didn't fit the idea of what a genius should be like. McCartney liked being a family man. He liked being a dad. Around this time and after the breakup, he was having photos of himself taken with his baby and with the children, with Linda, living on a farm. That's not what a countercultural drug-taking genius is supposed to do. This guy is just shallow and superficial. And now, I think our idea is about masculinity and genius have changed a lot over the last, whatever, it's 40, 50 years, but the story of the Beatles is only just catching up with it. And so, I think it's time for a new story. Russ Roberts: So, the other way to think about it, I think, is that Lennon was the iconoclast. Paul was the conformist. He was square. Lennon was hip. He had vetted hip, actually. He was hip before there was hip alongside the other extraordinary performers of the 1960s, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, and so on. And, McCartney doesn't fit that image visually. He has a cute baby face. He does like some bourgeois things. |

| 14:35 | Russ Roberts: But, here's the thing that blew me away. There were a lot of things blew me away about this, the story and the book. So, I have to tell you, I'm born in 1954. So, in 1964, the Beatles were on Ed Sullivan. I'm 10 years old, so I remember them pretty well. Their first album is 1963, Please Please Me. Their last time in a recording studio together, correct me if I'm wrong, is 1969 with Abbey Road, or at least Abbey Road was released in 1969. Let It Be comes out after that. But, they'd recorded that before. That was sort of a leftovers thing. So, this is stunning. There's two things that just blew me away. The entire time of the Beatles as public phenomena is six plus years, seven-ish, maybe eight if you count all the way through, Let It Be. But, their time together in the recording studio is--it's roughly six and a half, seven years, correct? Russ Roberts: So, during that time, they released 13 studio albums, including a double album, the White Album. They've lived together, they've had things happen to them that's never happened to human beings before, in terms of their celebrity, popularity, and so on. They stopped touring in 1966. So, for the last four-plus-ish years of the band, they're only in studio. They have lived 10 lifetimes of music in terms of how their music changed; sex, drugs, fame--in seven years. Paul McCartney--I didn't realize this--Paul McCartney, when Abbey Road comes out is 27 years old. He's a kid. I mean, relatively, from--he becomes famous when he's 20 and for seven years, and Lennon, who is a little bit older, go through this unbelievable journey. How did they survive that? How did they go on? There's a lot of gossip and conspiracy theories about Yoko Ono and breaking up the Beatles. I can't conceive of how they stayed together through this journey for as long as they did, and how short it was; and what they accomplished is mind-blowing. Ian Leslie: I'm so glad you said all that. You said it brilliantly. And, because part of the aim of the book is to just recapture our sense of astonishment about the Beatles, because they've been part of the cultural furniture for so long now we just think, 'Yeah, that's the Beatles.' It's like water for fish. They surround us. They're part of the atmosphere. And, I just wanted to kind of, in the book, take a step back at several points and go, 'What the hell happened here?' There is nothing like this in the history of pop and rock. There's nothing like this in the history of culture. It is an incredible story. You're absolutely right. It's seven years of recording music, seven years of fame, and then they're out. And they're out at the kind of peak of their powers, by the way. So, they're making some of the best music they ever made. They're selling more records than ever. I can't think of any other examples of bands that do that and then decide--right? So, there's so much that is extraordinary about it, and I think your question is the right ones. Sometimes the question of their breakup is approached from the angle of: So, why did they split up? They could have gone along. And, actually the question should be asked the other way around: How do they stay together for so long? And, the question is particularly pertinent because these guys were all very willful and volatile people. And, the chemistry between Lennon and McCartney was very close, but very volatile; and it was an unstable kind of compound. Right? So, they're always kind of jiggling against each other. And, I tried to show that from before the pre-fame days: you can see them coming apart at various times and then coming back together. And Lennon, of course, in particular, he's unstable himself as an individual. He's psychologically unstable. You start to understand why when you look at what happened during his childhood--this incredibly, incredibly tough, confusing, baffling childhood that he had. And then, when he's an older guy as an adult, he gets into drugs and starts taking too much LSD. He was violent. He could get very drunk and be violent. He was a real-- Russ Roberts: A mess-- Ian Leslie: He was a mess. It was a mess in some ways. And yet, somehow, the group, and particularly Paul, I think keep him in the fold, keep--just about channeling his immense talent into the group. But, finally, as they get into just the second half of their 1920s--as you say, they're still young--the strains that are put on them by all the legal and the business things, that relationship finally starts to kind of stress and crack and break up. But yeah--the closeness of the relationship is kind of what keeps them together. But, at some point, because it was so close, it had to explode, and in quite a spectacular way. This was never going to be an amicable partner parting where they go say, 'Yeah, you go your way. I'll go mine.' Handshake. Great friends and all that. I'm sorry. That was never going to happen. This was way too intense. |

| 20:34 | Russ Roberts: And, as music fans, for the groups we love, we all want them to stay together and keep producing music. We wish we could go see them at Six Flags. Yes, one of them would be gone, but we'd find there were substitute and we'd hear the old songs over and over. They never went through that phase. And certainly, when they went solo, they rarely performed. They never leaned on their fame. Their desire for innovation is, I think, unparalleled. They reinvent themselves in that seven years numerous times musically. And, that is--well, let me say it this way, and I'll let you just react. In 1964, when they're on the Ed Sullivan Show--I remember watching it with my parents--and my dad very confidently said, 'They'll never last.' And, it's hard to remember how intense the passion for this foursome spiked around the world. We had some of it with Frank Sinatra, we had some of it with Elvis Presley. This was different. Women screaming through an entire concert, convulsed with intense longing. I don't know even how to describe it. You can watch--there's video all over of it. And, my dad said, 'Oh, this is just some goofy, goofy thing.' My dad was half right in the following way. If had been the end--if the Beatles had been a group that honed the kind of music they were producing then--"I Want to Hold Your Hand," "I Saw Her Standing There": they're very catchy songs; they were great pop songs--I think people would look back on and say, 'Yeah, they were influenced by the Everly Brothers. They were kind of like them, but a little bit better.' But, what made them so extraordinary, and the reason my dad's prediction is ludicrous, is that they didn't stand and stay there. For people who took as many drugs as they did, their productivity and devotion to their craft is just hard to believe, hard to understand. The creative dynamism and the reinvention--the constant reinventionwhich must have been exhausting. And you chronicle the toll it took on them as friends and as human beings. It was just extraordinary. Ian Leslie: Yeah. And when you think about it, they effectively had to invent the idea of reinvention, if you see what I mean. There's a point in my book where I say it was a lot harder for the Beatles at every stage of their career to do what they did because they didn't have the Beatles' example to follow, right? So, every other brand, every other artist that comes after them, they're working in the wake of the Beatles and they go, 'Okay? Yeah, well, this is how to think about it.' And, you might think, 'Well, I'm an artist. I want to do things my way. I have integrity. I don't want to repeat myself.' All that kind of stuff, which we take for granted now, is the standard kind of pablum of musical artists. The Beatles had to kind of invent that for themselves. There is them that determined they were going to take themselves seriously as musicians and as artists who wanted to do something new every time. And, yeah, the productivity is just incredible. Partly that was obviously just these incredible commercialist constraints--that's not the word--but imperatives that they had to follow in the early years. But, actually, it becomes apparent towards the end of the 1960s: they're just going into the studio and recording because they love to do it and they want to do it. And actually, in the last year, 1969, when they are effectively splitting up, they actually record more songs than ever. The incredible number of songs they record--they record two albums in 1969. And, the more stressed or more emotionally stressed they got, the more music they made. Because they put everything--they processed everything--through the music. So, yeah, I think you're right. Just that sense of 'we've got to move on' is maybe their kind of greatest legacy apart from the songs and the music itself. This is that sense of how to be a popular artist. |

| 24:53 | Russ Roberts: When you go back and look at those old video clips of them performing either on the Ed Sullivan Show or at Shea Stadium, the other thing that's crazy is they stopped touring and giving concerts in, I think, 1966. Which is also unheard of. The idea that they would just become a studio band is crazy. But, when you go back and watch those early performances, it's a little hard to understand the hysteria. Again, part of it is because we've already lived through it. It's part of our wallpaper. But if you say what was so different about the Beatles in 1963 and 1964, you say: Well, good harmony. They had good hair. They had a certain rebelliousness that appealed to the zeitgeist of the time. They wrote very nice pop songs. The lyrics are very mundane. They're not magical in those early years in any way. What struck me, going back and listening--and what's wonderful about your book is as you do rediscover their music, and it's been playing in my head all week--it's been interesting: literally over and over again, different songs--there's something about the sound of their voices together, what you call the grain. It's part of what makes Simon & Garfunkel special, obviously, and many other--the Beach Boys had. Every harmonizing group has a particular sound. There's something I think about--especially Paul and John--singing together, that is magical. Do you agree? Ian Leslie: Oh, absolutely. And, we are talking about being re-astonished by them again. Just think about it. Like, okay? We recognize the fact that these two guys are amazing songwriters and they come together and make each other better. But, that's an independent fact from the fact that they're both amazing singers. Those two things needn't have gone together, right? Russ Roberts: Bob Dylan is proof of that. Ian Leslie: Well, that's another question. Russ Roberts: Well, I like Bob Dylan's singing, but no one would say he has a great voice in the standard dimension. Ian Leslie: They both turn out to be incredible singers--just individually. You'd put them both in the kind of top 20 greatest rock singers, I think. And, not only that, their voices blend. The ranges overlap and then exceed each other in just the right way. And, they're similar to each other, but different at the same time. So, yeah, the sound of their voices is really, and the sound of their harmonies is so central. Maybe the kind of central thread of the Beatles sound. And, that is a throughline from the early days right to the end. I would just say about the early songs, I have a slightly different view on those early songs. I think they are more innovative and stranger than we can recognize now. The chords they were using--in fact, talking to Dylan, Dylan recognized that earlier on. He said something about the chords are outrageous, but the harmonizing makes it all make sense. He saw that quite early on. He is like, 'These are actually musically very adventurous.' "She Loves You"; "I Want to Hold Your Hand." They're actually musically very innovative and sophisticated songs, but they're so condensed into these incredible little bombs--sort of nail bombs full of hooks--that we don't recognize it. And then, the other thing about those early songs, what made them sound different, and part of what generated this incredible response from teenagers is that they are soulful. They are emotional. They're not just going through the motions and writing a pretty pop song. They disdain that kind of Cliff Richards and The Shadows thing: You have a neat little pop song, you do a nice little dance routine, you go on TV, oh, isn't that nice? And, they wanted to get back to what they saw as the kind of spirit of early rock and roll, which is Little Richard and Elvis Presley, which is grabbing you by the shoulders and say, 'Listen to this.' You can hear it particularly in both of their singing. Lennon's voice in particular, just that kind of raw emotion and lust and desire that you can hear it in his voice. And actually, the lyrics are not all simple and nice. Look at "Please, please me, like I please you." It's kind of sexual and it's also jealousy and anger, and there's all sorts of, like, quite intense emotions in there. And, I think teenagers, who are obviously cauldrons of emotion, got that better than the adults at the time. Russ Roberts: That's very well said. And, I think you could also, in a way--maybe as you point out, first of all, they're writing their own songs. Elvis Presley is not writing his own songs. Frank Sinatra is not writing his own songs. Frank Sinatra, the other--those are the three biggest phenomena of the 20th century, I would say, in terms of musical obsession. Frank Sinatra made it sound like he was singing a song he had written, but he hadn't, right? He came across as if he was pouring out your heart to you, which is why he was so effective. But, in a way--and tell me if I'm wrong, and you may have written it--they're writing their own songs, as you said, that was unusual, but they're singing them in a way which is not performative in the standard sense of: Here's a perfect composition. I'm going to share it with you; you can listen. But rather: Listen to my heart. And, I think obviously that's at the essence of rock and roll; but it has an immediacy as you point out that was deeply effective to teenagers, but also I would say it was very appropriate for the time. I think with the 1960s, the thirst for authenticity, the rebellion against authority--it was kind of a perfect match. Ian Leslie: In a way that's kind of their great hidden innovation--hidden in plain sight--which is the vertical integration of songwriting and performance of songwriting and singing. As far as they were concerned and sofar as they had models--and one of the themes of the book is they also had to invent their own models because they didn't have them--they were thinking about Rodgers and Hammerstein, maybe Leiber and Stoller when they started writing songs. Nobody wanted to see Rodgers and Hammerstein perform their own songs. Nobody knows what Leiber and Stoller sound like when they sing. So, this is a new thing where--not completely new, but they saw something that wasn't conventional or standard. And so, 'We can actually write our own songs and sing them, and we'll sing them better because we are putting our emotions into it, and that'll be evident.' So, they intuitively landed on this idea of the pop song as not just a catchy tune, but a vehicle for the transmission of emotions. And, in fact, they make that explicit: early in the mid-1960s. There's some interviews with them where they say, 'People don't understand what pop music is. For us, it's about communicating an emotion, a feeling. That's what we try to capture first, and then we build everything around that.' And, that was a massive innovation and in the way that they saw pop music. |

| 32:29 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. We're not going to go into the details of the friendship, how it's revealed in the music. You have to read the book to really appreciate it; and it's magnificent. And I'm just going to say in passing, I cried a couple of times reading this book because the emotion that is released and unleashed in their friendship that's expressed through their music--and it's imperfection--the imperfection of their friendship and the challenges of ego and money that over that seven-year period become ultimately insurmountable and that end shortly thereafter in human years with the death of John is a truly heartbreaking story. So, we're not going to talk about it. You can say something about it for a minute, but I want to move on to a different thing. But, say something about it if you'd like. Ian Leslie: Yeah, I mean, I would just say--it sounds a bit odd to say--I'm glad you cried. But I am glad that you had emotional response to it, because that was an absolutely big part of the aim of the book, is to show people what a moving and emotional story this is. And, that's one of the things I think that previous Beatles books and scholarship had not really got to. Russ Roberts: And, in the course of reading the book, I remembered a 1963 pop song my dad loved that is a counterpoint to the examples we're talking about. It was called "Sailor Blue," and it went--the refrain was: [Russ sings:] Blue, sailor blue, I'm as blue as I can be

Because my sailor boy said 'Ship ahoy'

And joined the Navy. So, that's that era that "I Want to Hold Your Hand" is in; and "I Want to Hold Your Hand" has a urgency and power to it that is new. Ian Leslie: Absolutely. And it's so radically different from--that kind of song that you just sang, that dominated the charts along with lots of novelty acts and actually did way into the 1960s, quite a long time before other groups and other artists caught up with what the Beatles were doing. They were making this direct bid to the heart and to the body in a way that was just sort of knocked you off your feet and was much more powerful than most of what was going on--with the exception of, I would say, Motown and some of the Black acts in America that they were deeply influenced by. But, other than that, it just sounded incredibly different coming out of the radio. |

| 35:10 | Russ Roberts: We recently had Dana Gioia on the program talking about opera and songwriting. And in most of music history, a lyricist collaborates with a composer. There's a handful of successful people who can do both. They're very rare in history of certainly of opera and musicals; and in most of successful what are called American Standards--it's Leiber and Stoller, it's Rodgers and Hart, it's the Gershwin brothers. Paul and John wrote lyrics and music together, which is, I think, extremely unusual. I think you note that. Is there any parallel to that? I guess many bands write music together, but they usually credit Robbie Robertson when the band would produce a great song, or Levon Helm. All--almost all? all?--are Lennon-McCartney, and they collaborated in an extraordinary way that we have video of and writing about. Talk about that collaboration, the process. Ian Leslie: Yeah, yeah. Well, there's a couple of things to say here. One is that, as you say, they both wrote words and they both wrote music. Now, it doesn't mean that all songs were equally written, and some of their songs particularly as their career goes on are independently conceived and maybe mostly written by one or the other. Although actually the collaboration goes on pretty much until the end, even if it's in subtler ways than it was happening at the beginning. But, the point is that, as you say, there was not this division of labor that was the form. Again, there was no model for this. And, it took them a while. And, Brian Epstein says at some point, I keep having to say 'No, they both do both, actually,' because they kept being asked, 'Who does the words? Who does the music?' Russ Roberts: He's the manager. Ian Leslie: They both do both. Sorry. Yeah, Epstein, their manager. And so, yeah, it was very unusual at the time; and actually is still unusual, as you say. I actually can't think of any. I'm sure there are some, but Keith Richards and Mick Jagger--mainly Jagger writes the words; mainly Richards writes the music. Sometimes one of the other will dive in and do the other. But, there's a fairly clear division of labor there. And, there just wasn't with Lennon and McCartney. And, they're both incredibly good at lyrics as well. Certainly when they wanted to be. You know, McCartney could write "Eleanor Rigby," and John could write "I Am the Walrus." So, yeah, it's just another way in which they were even more unusual than we necessarily recognize. Russ Roberts: Talk about George Martin that many people listening will not have heard of. I don't know if you're going to agree with me, but when I went back to the songs and re-listened to many of them that I had known but not paid much attention to and listened to the ones that I loved, one thing I was struck by was how to my ear they're overproduced. I had a longing for the Beatles unplugged, a sparser version. But, when you go back and listen to a song like "Strawberry Fields" or "Penny Lane," or almost every song on Abbey Road, there's so much going on all the time of different kinds, and there's strings; and there's an orchestra; then there's noises that aren't musical and all kinds of stuff. And, you call it the wash of sound. I don't know if that's a standard term, but I thought that captured--I wanted a little bit of a more placid lake from time to time. Ian Leslie: I mean, I don't really agree, but we will have of different opinions. And, there is an argument that around the kind of psychedelic era, "Sgt. Pepper," "Magical Mystery Tour," there was a little too much going on. I can kind of see around that time maybe, and they kind of agreed. So,when they do the White Album, which still has some big productions, but the White Album is more about the group again, it's more about the four of them playing guitars and drums, and they sort of go back and forth. So, Abbey Road is a bit of a fusion between the two. It's kind of group-centered, but there are some big productions as well. But George Martin is important to the story in so many ways. Brian Epstein is their manager, and he meets them in Liverpool, and he's the one that finally gets them a break in London. Because it's very hard to get a break in London. Because, in London they were, like: Well, I barely know where Liverpool is. The idea that there is going to be a pop act coming out of Liverpool is just ridiculous. And this group, they don't even have a lead singer. It's not: John and The Beatles. It's: The Beatles. And, also, what is this name? The Beatles. It's so weird. So, every time Epstein tried to sell them into a record label, he just met with this wall of kind of, like, 'What are you talking about? Don't understand where you're--' And, they write this. I mean, it's just weird. Finally, he meets George Martin, who is writing this small label, which is part of a big company, EMI [Electric and Musical Industries]. And George Martin is a comedy producer. He's had some hits with comedy performers. And he's very creative, very innovative. Comedy records, you get lots of sound effects and odd things going on. So, he was used to kind of using the studio as almost as another musical instrument. And, he's a bit dissatisfied with his job. He doesn't feel like he's getting enough credit from his bosses; and he hears something in this weird bunch of guys from God knows where, as far as people in London are concerned. And, he goes, 'Well, maybe I could do something here.' And, he's very musically educated, right? He's got a classical music education; and he gets it pretty quickly. He gets that these guys are actually operating on a high musical level, even if they're uneducated, relatively speaking, in musical terms. And, it's his generosity of spirit and his imagination and his kind of vision which really opens up the door for them, because he pretty quickly recognizes: We're not just going to do recordings, which are the live performance transferred onto a record, which is basically how most people saw the point of a record. We can actually make new kinds of recording, and we can use the studio as an instrument, too. And, the Beatles were into that, and he got it very quickly in a way that probably nobody else would have done. And so, it was his ability to rate them, to see that these working class--or at least not highly-educated London guys--were onto something really sophisticated and clever here. And also, his ability to think outside the boundaries of pop music and his willingness to do something different: it was crucial to their evolution. |

| 42:23 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about the song "Yesterday." I looked it up. You can't really look it up: it's kind of silly. But, I found one website that said it has been covered approximately--approximately, I like that--2,200 times since it was released in 1966. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, it's the most covered song of all time. Regardless of what the exact number is, people really like the song, and it's been recorded by a lot of different people. Paul wrote it initially, and it's a source of jealousy that you recount in the book. But, how did Paul come to write it? It's kind of extraordinary. Ian Leslie: He just woke up one morning in his flat in London with this tune running around his head. And he gets out of bed, and he's got a piano in his room and kind of plays the melody that he can hear in his head. And, it's so lovely. And so--it feels like a classic to him--that he thinks, 'Well, it must be another tune. I must have heard it before. It can't be from me.' And so, he starts humming it or playing it on the guitar or on piano to pretty much everyone he encounters, for quite a long time. He plays it to George Martin, 'Do you recognize this, George?' He plays it to John, of course: 'Do you recognize this?' Plays it to several other people and goes, 'Do you know this? Because it's in my head and I can't--' And, everyone said, 'Oh, this maybe sounds a little bit like this, a little bit like this, but it doesn't really sound like anything else.' And, eventually he comes to accept that, 'Okay, I've written this tune.' He's been using the placeholder words: 'Scrambled eggs. Oh my darling, how I love your legs.' And, he starts taking the song seriously and starts going, 'Okay. Well, this song feels like it's about yesterday.' And then painstakingly kind of puts together the rest of the song. And, it's a really kind of important song in so many ways because--first of all, it becomes this massive hit in America, first. Unexpectedly. Andsecondly, because it is performed and written by Paul. There's a string quartet, obviously, which he and George Martin put together. But other than that, none of the other Beatles are involved. And, this becomes a source of uneasiness and tension between him and John, because from John's point of view, 'Well, first of all, this isn't really rock-and-roll at all, is it? It's something different.' And secondly, 'If Paul can do this and just stand in the spotlight and sing a song by himself, and it's this massive hit, and lots of people are covering it, then maybe Paul doesn't need the Beatles. Maybe Paul doesn't need me.' John was somebody who, right from childhood, was terrified of being abandoned. It had happened to him, and it really hurt him when he was young. And, I think those insecurities started to play into the relationship around this time with real force, because it suddenly looked like Paul might be able to step aside from the band and have a solo career. And so, the tensions between them really kind of ramp up around this time. They're actually very productive tensions. But, "Yesterday" becomes this kind of real source of tension between them, particularly for John. Russ Roberts: But, there's another piece to this, which you write about a lot, and this small little look at one song is--in many ways encapsulates the challenge of this friendship. I think--at least based on the way you wrote it, you may have said this, literally--John recognized that this was the best Beatles song ever written, or at least one of the greatest. And he didn't have much to do with it; and it hurts. Ian Leslie: It hurts and it's kind of terrifying. And, equally from Paul's perspective, it's a moment where he realizes the full extent of his talent. So, this was John's group, originally; Paul joins. Now, they quickly become co-equals in the group; but that residual sense of John being the kind of leader of the band remains. And certainly in the early years, he is the most prominent voice. Those early albums, it's his voice you hear the most. Paul had some huge hits: "Can't Buy Me Love" and "I Saw Her Standing There," and some of the kind of best songs, but John dominated to some extent in those early years. And, it's really only when--kind of 1964, 1965, 1966--that Paul's talent, the full scale of it, starts to unfurl. And, "Yesterday"--when he realizes what a great song it is and that he wrote it, and that he actually performed it as well--he starts to think, 'Wow, okay. This is it.' And, really kind of rises up and becomes this at least equal kind of creative force to Lennon, from the mid-to-late 1960s. So, yeah, it is a pivotal song in the relationship, and it's a pivotal song in the story of the group's musical development, too. Russ Roberts: And John is older, right? He's two years older? Russ Roberts: Is it two years? Ian Leslie: Yeah, year and a half, I think. Yeah, year and a half, two years. Russ Roberts: So, that's irrelevant through most of your life. But, when they first meet in 1957, Paul is either 15 or 16, and John is 17 or 18, and that's an enormous gulf. Right? Ian Leslie: Yeah. Yeah, absolutely. So, Paul is the junior partner. As you say, when you're teenagers, these gaps of a year and a half, two years, they matter a lot. Now, Paul, unlike the other members of The Quarrymen--which was the group that existed before The Beatles--pretty much became John's musical equal quickly because he was obviously so gifted, but I think it took a long time for that sense of being the younger partner--the junior partner in the relationship--to fade away. And, it took a while for Paul to really expand his musical and emotional range. And partly, he was influenced by John. He got better because a big part of that was seeing what John was doing with songwriting. John was introducing this whole range of emotions--negative emotions, anger, jealousy, reproachfulness. And Paul starts to put those--Paul had been pretty much been either a big kind of joyful explosion of emotion or a beautiful romantic side, like "Things We Said Today." And, from the late, early- to middle-1960s, he starts to put these more complex, difficult emotions into his songs. "Yesterday," you could say was part of that, but also songs like "I'm Looking Through You," and then a bit later "For No One"--which are really sad, difficult songs. And, I think he's learning from John. He's learning from others, too, like Dylan, but he's learning from John. Russ Roberts: It's worth noting, and when I think about this--[?]people think about this--when I think about the Beatles' singing, there's a lot of screaming in various parts of their oeuvre. Right? They sing very sweetly on many, many songs, but on a lot of songs, they're yelling and then literally emitting screams. Not just singing in a screaming style, but screaming. Ian Leslie: Yeah. This kind of, like, atavistic, animalistic, wild screaming. Famously on "Twist and Shout": I actually think it's Paul's scream that really cuts through on that one; and John's kind of incredible singing, of course. But, yeah. And I sort of, like, traced that through the career of the Beatles. And, going back to what we were saying about them wanting to somehow break through the veneer of niceness and neatness, superficiality of the pop world as they saw it, right? They always thought that the acts they saw on TV before they were on TV just seemed kind of phony to them: they didn't really mean it. And they wanted to kind of, like, just sort of grab you bodily almost with their music and with their singing and make you feel something very, very intense and very strong. And then the screaming is part of that. |

| 51:33 | Russ Roberts: You quote something I've mentioned on the program recently, Tolstoy's definition of art, and you quote, "To transmit that feeling that others may experience, the same feeling, and they did that par excellence." I don't know if that's the right way to use par excellence. I don't know if listeners remember, but a long time ago I interviewed Chuck Klosterman on his book, But What If We're Wrong? And in that book, he speculates that when people look back on the era of rock and roll--which is a very short window--there will only be maybe one group that gets remembered. One voice. He gives the analogy of marching bands' music: like, we've heard of John Philip Sousa. But, John Philip Sousa was not the only person writing music for marching bands; but he's the only one who got remembered, and that's it. That's all you get. And he speculates: 150, 300--I don't know what the years are--but hundreds of years from now, people will look back on this bizarre, glorious, wondrous moment in the 1960s, and there'll be one name associated with rock and roll. And, he looks at--I think he considers the Beatles, he considers Dylan. He says, 'It might even be somebody who is obscure: we haven't heard of him--an academic who's while on earth with some cool hip theory.' And, I think he settles on Chuck Berry as his guess. But it could be the Beatles. But here's the irony for me, and I'd love your reaction. John definitely saw his identity as a central member, if not the dominant member, of a rock-and-roll band. But, if you look at the Beatles' immortal songs, the songs that will be sung in 2050 in a hundred years, this is my list. It is colored by my personal taste, obviously. So, yours will be different, but it's striking how un-rock-and-rolly they are. This is my short list: "Let It Be," "In My Life," "Yesterday," "Hey Jude," "Long and Winding Road," "Here, There and Everywhere," "Michelle," and "Eleanor Rigby." There's a little rock in some of them, but they're mostly not what you would call rock-and-roll songs. They're mostly what we would call ballads. All of them have an incredible elegiac yearning power to them. And, what do you make of that? Do you agree or disagree? Ian Leslie: I don't necessarily agree with your list, although I do think those all wonderful songs that will last a long time. I know that they're almost all Paul songs. Russ Roberts: Is that true? Not on purpose. Ian Leslie: Yeah. No, I know. That was just funny. Yeah, there maybe be a reason for that, but we can come back to that. But, first of all, I think they are more likely to be remembered than anyone else. I mean, I think more than any of those other artists that you mentioned. Maybe Dylan, but because Dylan is not quite as musically--certainly lyrically, poetically right?--he is probably kind of peerless in the work. But musically, perhaps not quite on that level. Right? And, music is a very powerful memetic, kind of cultural property. So, I do think that the Beatles are kind of the ones that will be remembered. I see them as Shakespeare versus Ben Jonson and Philip Marlowe, right? Jonson and Marlowe plays still get performed, still get studied, but Shakespeare isn't just another Elizabethan Jacobean playwright, is he? Right? He's on another level from those guys. And I think, I suspect, the same is going to be true of the Beatles and the way they're seen in a couple of hundred years' time. And then, yeah: so your question about how many of their songs--which was so many of their songs are just not rock and roll-centric--is really interesting. And, I do kind of make the effort in the book to show that they were actually part of the great river of 20th-century popular music, and that many of the tributaries that feed into the Beatles' sound come from before rock and roll. They didn't actually renounce everything that had gone before when Elvis and Chuck Berry arrived in their lives. That's what turned them on. That's what they got incredibly excited by. That's what got them up there playing guitars. But, they still loved the music of their childhoods. And the music of their childhoods was from the Great American Songbook. It was English music hall, it was big band, kind of jazz band--tried jazz stuff like Paul's dad used to play. And, Paul in particular--but actually John too, although he was less likely to admit it--they never stopped loving those older forms of music, and they took them with them into the new era of rock and roll, and then rock and pop as they kind of expanded its horizons. So, even as they were pushing forward the boundaries of pop with "Tomorrow Never Knows" and doing these kind of incredibly futuristic, avant-garde, psychedelic experiences, they were also throwing in musical hall and Disney and Rodgers and Hammerstein's and all sorts of things. So, they're really bringing together all these different streams of 20th century music. And, that's why I think you're right. I think a lot of the songs that they're really well-known for, you can trace back to older traditions. Russ Roberts: Now, I made my list based on Lennon-McCartney's songs. I think "Here Comes the Sun" will be performed for a long time, but that song is credited in some dimension, and if not in terms of copyright-- Ian Leslie: It's George's-- Russ Roberts: to George Harrison. In what sense are those Paul songs, given that they're all Lennon-McCartney? Why do you call them Paul songs? You said many of those are--not all of them, but many of them that I listed. Ian Leslie: Yeah. So, when I talk about a John song or a Paul song--so there were a few songs, particularly early on, and then one or two examples later, where they're really co-written: they're written face to face, throwing out lines to each other saying, 'How about this quarter? How about we do this for the middle eight? What do you think?' 'Well, no, no, we should go here.' "I Want to Hold Your Hand" is written like that. You can't tell where one person's contribution begins and the other one ends, right? But, for the most part, they would independently propose ideas to each other. So, they would come up with their own song and say, 'How about this?' And then, the other one would modify it, make suggestions, sometimes explicit ones. Sometimes I think just very subtle ones that perhaps wouldn't have been recorded. There'll just be a look on the face or a shrug or a kind of, 'How about this?' So, I think nearly all their songs, they were influenced by the other, but for most of them you could see that one of them proposed it and conceived of it and was kind of the creative director of the song, if you like. So, the group would help them put the song together, but it was ultimately up to Paul to make the decisions on Paul's songs and up to John to make the decisions on John's songs. Does that make sense? Russ Roberts: Yeah. |

| 59:22 | Russ Roberts: Of course, I've listened to "Eleanor Rigby," I don't know how many dozens of times through my life, some intentionally, some unintentionally: it gets played a lot. For me, it's in a class by itself, lyrically, and in terms of its composition and it's literary nature. Why are there so few songs in their work that--at least maybe you don't agree, but, for me--that could be poetry? Pure poetry, not enhanced by the music. The music is extraordinary and the arrangement is extraordinary, of course. What do we know about that song? Why does it sound at least so different to my ear? Ian Leslie: I don't know. One of the many mysteries of the Beatles is where a song that comes from. It's very difficult to see what the models were. Again-- Russ Roberts: There's nothing like it-- Ian Leslie: Nothing like it. Maybe the [?King's? inaudible 01:00:30] did it. Russ Roberts: Leonard Cohen later. Ian Leslie: Yeah. Bit later. Russ Roberts: Maybe. Ian Leslie: So, I think there was a kind of King's song where he kind of tells a story about--but it's not really the same. And, to write this kind of character, this two intersecting narratives in a song about these strange kind of lonely characters that are, again, very far from hip rock-and-roll people, and to write a song essentially about death and the afterlife, whether or not there's anything that comes after it. And, he was 23, and he's, like, king of the world. Russ Roberts: Who is 'he'? Ian Leslie: Paul McCartney. Sorry, Paul. Russ Roberts: Yeah, go ahead. Ian Leslie: Yeah, so this is a Paul song that John contributed to, but this song was led by Paul. So, it's just utterly incredible. And, yeah, the lyrics are literate without being pretentious, I don't think. They don't come across as try hard. They're just kind of clever. And the patterns of the sounds and the words: When you say it's like poetry, it really is quite poetically structured. And then, of course, they find this with--George Martin does this incredible string arrangement, which is very biting, again, quite dark, and then sort of musically, you get these kind of counterpoint melodies happening at the same time. There's a lot going on, but it feels completely kind of immediate, right? You don't feel like you're having to struggle to understand this incredibly complex song. It just kind of hits you. So yeah, I do think it's one of their greatest achievements. Russ Roberts: And, it's what? Two minutes long. Ian Leslie: So many of the Beatles' songs are like that. They're just so short. Like their career: they come in, they change you, and they get it out. Russ Roberts: And, unlike what we're talking about before, "Eleanor Rigby" is an attempt to move us about--not about them, at least explicitly; it's maybe implicitly about them; they would be thinking about their own loneliness and their own death--but they're telling a story about someone else in a very literary way. Ian Leslie: Yeah. They were interested in other people. I mean, this was a particularly kind of McCartney attribute, and he told quite a few stories in his songs about women, and not just as sexual objects of desire. Again, very strange thing for a young pop star--a young man--to do. But when he writes "Lady Madonna"--or "Another Day" is a kind of 'nother example--and he's finding these stories about people who are sort of disconnected from society in some way. And he's kind of really curious about them. Again, it's just something that, I don't know where it came from because nobody else was incorporating those kinds of thoughts and emotions and stories into pop music, but it's one of the many things that make them very distinctive. |

| 1:03:49 | Russ Roberts: I recently saw the movie Maria with Angelina Jolie. It's got some fine things in it, and a friend of mine was saying that here's this woman who has inhabited characters on stage with such emotion, and it eventually bleeds into her daily life. Her ability to separate--the movie is in many ways about the challenge of separating reality from one's own imagination. In the movie, it's hard to tell what she's seeing versus imagining. Are the people that she's talking to real or are they figments of her imagination? And, I was struck by having just read your book that the Beatles have to deal with this incessantly. Their identity as a Beatle is at the center of their existence. At the same time, to have to wear that mask--that costume that the world has created along with your own efforts--is so destructive. And, a lot of the book is capturing the dysfunctionality of their existence in this time. And of course, it has lasting damage in certain dimensions, I'm sure. But, talk about that issue of their identity--how it was hard for them to have that level of fame and expectations from the people around them. Ian Leslie: Yeah. Again, there's no real models for this, for being pop stars aren't quite on this scale. And, equally after they split up, there weren't really any models for being an ex-member of a group, an ex-Beatle or an ex-anything. Again, they're always kind of at the forefront of what's going on, whether they wanted to be or not. I think they dealt with it as well as any four young men could have dealt with it. I think it absolutely helped that they weren't a solo act and there wasn't a front man. It wasn't just one front man. This was a group of four, and they were able to create their own protective bubble by sort of so turning inwards. There's a nice little observation that Ringo made later on where he said: 'There will be a big party at some sort of, say, at the American Embassy or somebody's house; and all the stars were there. Everybody wanted to meet us. And, we would just meet up in the bathroom and light up a joint--just the four of us, sort of shutting ourselves away.' And they managed to maintain that. They weren't always together as a foursome, but when they were together, they were inside that bubble again. And, they kind of protected each other. And kept each other sane, because they were teasing each other. They had that kind of relationship. But, yeah: the personas that they were kind of created in, say, "A Hard Day's Night"--where John was the scathing, cynical one, and Paul was the cute one and Ringo was this slightly kind of lost boy, and George is a bit sort sulky--they all had a grain of truth in them, but they didn't really reflect the full range and complexity of these characters. And, they started to really chafe at that, as part of the reason they stopped touring. They didn't want to be exposed--always on show to the world, always having to do press conferences, always being screamed at as they ran into a hotel. It really felt like they were in a trap, in a kind of weird prison by the end of the touring days-- Russ Roberts: 'Help! I need somebody'-- Ian Leslie: Yeah. So, John's song is literally a cry of help. He wasn't just writing a pretty pop song. We've been talking about the way that they put their emotions into their songs, and he was doing it very directly there. And, he was, effectively, having a psychological crisis, if not a nervous breakdown, caused by the disjunction between the public persona that he had as this happy cheery Beatle and what he was feeling inside, which was kind of confusion, disorientation, not really sure what he wanted to do. And, he writes this song, "Help!" And, it's really kind of expressing that confusion and disorientation to the rest of the world. One of the beautiful things about that song is that the backing vocals sound like a group of friends who are literally backing him up. And they start to sing the words before he sings them: "And now these days are gone, these days are gone." And I just think it's kind of typical of the Beatles' sound, the way they harmonize, the way that their voices interacted: they really convey that ethos of friendship and mutual support in the music. So, it wasn't just that they were friends and then they made music. You can hear the friendship and the love for each other and the support in those songs. |

| 1:09:20 | Russ Roberts: As I said, we're not going to go as deeply into what I think is the central part of the book. I want to encourage listeners to read it and viewers to read it. I don't think it's easy to talk about it. You did such a good job writing about it. But, if you could say something briefly about friendship: You've written one of the few rock biographies that I think mentioned Plato. I think you mentioned the "Symposium". And the "Symposium" is partly about friendship; and certainly Aristotle wrote eloquently on friendship. When you think about the attempts to write about what is special about same-sex friends who are not lovers--just friends--your book is one of the reasons such a powerful read is that you capture that. And, I can't think of any other things that are like that. Movies capture it occasionally. But that's really what this book is about. And, in a way, we haven't done justice to it, and I'm suggesting I don't particularly want to, and I'm not sure we can in a brief conversation. But, really, in many ways, your book is about something that is a tremendous gift that these two people had of caring deeply for each other, being able to express it through music, experiencing many of the same things together that no one else could understand, other than those four and maybe just those two, especially Paul and John; and that it lasts for such a short time, roughly 10 years, a little over 10 years as friends, and then falls apart; and then ends in the early tragic death of one of them. It's one of the saddest things that's ever been captured in a book. And, you did it amazingly well. I have nothing else to say, but you can react to that. Ian Leslie: Yeah, so it is a sad story. It's a joyful story as well, I think. Russ Roberts: Fair enough. Ian Leslie: And, you can't kind of separate the two. But, I would just say on the friendship thing, I do think it's absolutely fascinating because I do think their relationship was very unusual, this very intense. Platonic: I don't think they were having sex. But in every other sense, romance that's also incredibly creative and the creativity is part of the excitement and the sort of intoxication of the relationship. You do get these friendships now and again in--you could see them in cultural history. They are rare. And, I don't think there's any kind of exact analogy to Lennon and McCartney, but there are a few that I've been thinking about that are close or have similarities. And so, I was thinking about Coleridge and Wordsworth, these two poets who meet--one's older, one's younger, kind of wake of the French Revolution, they're very politically engaged. They love the countryside. They go for hikes. And they just start saying, 'Maybe there's a new way to do poetry.' And, they write poetry together as a very kind of intense relationship and really give birth to a whole--the Romantic Movement in English poetry. Just one example. The closest 20th century example is not actually for poetry or music: it's from the social sciences. So, a few years ago I read Michael Lewis's book, The Undoing Project, where he basically tells the story of the relationship between Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, the psychologists, Israeli psychologists. They meet in 1969, Tel Aviv, and their relationship is as intense as Lennon and McCartney, I would say. And, they really shut themselves away and together invent a new model of human rationality. And, the way that Lewis writes about it and the way that Kahneman talked about it to Lewis--because Michael Lewis interviewed Kahneman--is very much as a love affair. Kahneman's wife says to Lewis, 'Was it like a marriage?' 'No, no, no. It was much more intense than a marriage.' And, similarly with Lennon and McCartney, after they become effectively famous and well-acclaimed, they then find it hard to get along. There's questions of relative status and competition and conflict comes between them. And they drift apart. And they both feel awful about it, but they can't kind of work out a way to get back together. And, indeed, Tversky dies relatively early, leaving Kahneman to wonder about what happened there. So, that's another example of this kind of, yeah, very close, very intimate, very tempestuous, and incredibly creative male friendship, but there aren't many of them. Russ Roberts: I was thinking about Rodgers and Hart. You mentioned Rodgers and Hammerstein earlier. Rodgers and Hart. Lorenz Hart was damaged emotionally in a way that reminds me of Lennon--not at the same extent. Lennon was much healthier, I'm sure. But, Rodgers was fairly stable. Hart was this very mercurial, troubled soul. And they end up breaking up; and--I think I've got this right--Hart dies shortly after that breakup. But, what it is like to create something as extraordinary--forget the money, forget the fame, forget the rest of the package--to create something at all is glorious. To create it with another person and appreciate that they're not just tagging along--you may resent it at times, but that they are entwined with your gift in a way that makes it sweeter, there's nothing quite like that. Other than maybe making a child, which is similar in certain dimensions: kind of creative act with someone you love. So, it's complicated, but there's something--that bond is very powerful. Ian Leslie: And, I think we've seen McCartney come to terms with it over the years since John's death. At first, I think very difficult--it was very difficult for him. To lose someone you're very close to is always difficult. To lose someone when your relationship is not on the level that it was, and there's sort of some conflict there, but suddenly they're gone and you can't fix it, I think it's incredibly hard. But, I think as the years have gone by, you can see him processing it. And, now when he looks back on it seems to be with just an enormous sense of gratitude and love and a feeling of fortune: How lucky he was to have met John, how lucky they were to have found each other and to have created this magical, magical thing. And, I feel the same way: I think we're all very lucky that they met each other. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Ian Leslie; the book is John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs. Ian, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Ian Leslie: Thank you very much, Russ. |

At the heart of the success of the Beatles was the creative chemistry and volatile friendship between John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Listen as author Ian Leslie discusses his book, John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs with EconTalk's Russ Roberts. It's a deep dive into music and friendship as well as a revisionist history about how John and Paul created musical magic.

At the heart of the success of the Beatles was the creative chemistry and volatile friendship between John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Listen as author Ian Leslie discusses his book, John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs with EconTalk's Russ Roberts. It's a deep dive into music and friendship as well as a revisionist history about how John and Paul created musical magic.

READER COMMENTS

Bette

Apr 7 2025 at 8:39am

Thank you for this episode. As someone born in 1955, and a full-on Beatlemaniac at a young age (I turned nine in 1964), the Beatles hit me very hard. A couple of remarks on the conversation:

There’s an extended discussion of “Eleanor Rigby,” and rightly so. But I’m surprised that “She’s Leaving Home,” a brilliant — and I would argue, even more emotionally moving — followup. Perhaps it doesn’t have a catchy hook, so not as hummable as the earlier song. But it is, indeed, very much of a piece with “Rigby,” and deserves more recognition than it gets. Speaking of the juxtaposition of points of view in one song, “Leaving” uses Paul as a third-person narrator, and John as the first-person plural voice of the parents, to astoundingly plaintive effect. I happen to prefer it to “Rigby.”

I’m rather astounded that the name Little Richard wasn’t mentioned as a major influence on the Beatles. They themselves did so, frequently, when asked. You talked about the screaming in the Beatles’ performances, yet that came straight from Little Richard (who brought it, partly, from African-American charismastic church culture), Blues music, etc. There was only a glancing mention of this influence in the conversation, which is quite surprising. The Beatles made no secret of it, or of how this emerged during their wild-yet-formative Hamburg period.

Finally, given that we’re about the same age, I was startled to hear you say that John Lennon invented hipness. He certainly did not. White hipsters emerged in the pre-WWII jazz era, again taking much from Black culture, including “jive” talk, and became part of Beat culture, represented by Kerouac, Ginsberg, et al., in the 1950s and early 60s — which also hugely influenced Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and definitely Lennon and McCartney. Remember that both went to art college, and John’s books of random poetry and drawings were absolutely influenced by the Beats.

I’m a historian. In general, you can pretty much assume that very few trends emerge out of thin air. Lennon and McCartney were extraordinary, but that was partly because of those who came before them, and due to Brian Epstein’s and George Martin’s gifts for editing and refining.

Russ Roberts

Apr 7 2025 at 2:02pm

Bette,

Thanks for the thoughtful comments. Of course you are right, there was hipness long before Lennon. And he did have plenty of competition in the 60s.

And please remember I can’t do justice to a 400 page book in an hour plus long interview. There is much about Little Richard in the book.

Shalom Freedman

Apr 7 2025 at 10:08am

A wonderfully enjoyable conversation. Russ pointing out that the songs he loves the most are the more ballad-like songs echoes my own feeling. However, in the early years the faster songs were great for joyriding. The description of the friendship and the creative closeness, rivalry, and tension it involved was most insightful and moving. The songs are not in my opinion works of lyrical genius. Dylan is the songwriter of that era who was certainly beyond everyone else. The amazing and persistent popularity of the Beatles I think is due mostly to the music. Happy days are here and gone again for many of us oldies who still on occasion listen to it.

Brett Busang

Apr 7 2025 at 2:32pm

I grew up in Memphis, which was weaned, rather belatedly, in Elvis, yet was steeped in the blues that informs much of early Lennon and McCartney. (With Lennon, the influence ran as deep as any ever does. Being more of a chameleon, McCartney trotted it out r more selectively. Yet, of the two, he may have shouted more completely.

We can, I think, celebrate the UK for a blues fixation that permeated its popular music rather differently than it did ours. Any adopted child is more consciously favored – or denied – than his or her litter-mates. Which applies to the blues and Britain. Having come by it secondhand, it had much to prove. (No “bluesman” was ever more possessive than Clapton, whose attitude could be militantly defensive).

A circular movement of which I was unaware until it happened culminated in a novel called I Shot Bruce, in which The Beatles were fictionalized and transplanted to London. Though I haven’t lived in Memphis since 1984 – which had been much too long – I wrote it there. In it, the music I had heard growing up found a sort of pony express. As did the Beatles, whose screaming – sling with those who screamed for them – was initially heard just blocks away. These days, the blues have their own Disneyland, which has, in part, emasculated them. Yet a half-life survives in the way people have come to accept what only a Second Coming (in what I cannot believe) will scatter. Memphis is the sort of place that’s easily mythologized. People take what they want from it and go away more or less satisfied.

The Beatles came to perform – and to, somewhat sheepishly, come and see Elvis, who was dismayed by their idolatry. Yet all of Anerican music culminated, for the Beatles, in him. (Paul was, hands-down, the Elvis imitator you want in a karaoke contest – even if we’ve got him in Lady Madonna and a slew of other Elvisian iterations. Little Richard comes sailing in with Long Tall Sally – in fact, whenever McCartney hits a high note, he’s there.)

I’m here to suggest that The Beatles were such a hybrid that influences as far flung as the English Music Hall and Jazz Age musicianship could march in lockstep together. With a triumphant sort of yawp, Lennon and McCartney sought most to capture what both perceived, albeit unconsciously, to be theirs as well as history’s. Their cultural clashes, as well as reconciliations, are organically analogous. And, now that I’ve grown old in my own enthusiasm, I’m delighted to see it in so many others. And look forward to reading your most recent volume.

Matt Ball

Apr 7 2025 at 5:12pm

This was a fantastic episode – I put the book on reserve from the library after just a few minutes.

I, too, think that Paul is (still) underrated.

Just FYI – when I was in high school (early 80s), Eleanor Rigby was taught as poetry in English class.

Thanks again.

Gregg Tavares

Apr 14 2025 at 4:17am

I’m mostly enjoying the book, I’m on chapter 39 and often putting in the songs to review them with all the commentary which is interesting.

I was born in 65 and so missed the Beatles when they were in their prime but of course I love their music. Unfortunately, having missed their public appearances I had just the music to go on. So many songs are love songs both as the Beatles and from their solo careers that I took at face value. After reading about how they cheated on every woman they ever had a relationship with puts a big sour taste on their love songs for me. When a song says “I love you” all I can think is “but not really because in a couple of hours I’ll be the hotel room next door banging someone else”. Kind of disappointed it turned out to be all lies.

Fawn and Jim Spady

Apr 20 2025 at 9:49pm

Russ,

Thank you so much for your recommendation of this book. My husband, Jim and I have been listening to the book on Audible, pausing to listen to the songs used to title each chapter, (as well as others of course).

We both grew up listening to the Beatles, but listening to Ian Leslies, beautiful writing elevates our appreciation to a new level.

My Covid project was learning to play the Ukulele and I’ve played simple versions of many of the songs. I now have a much greater appreciation of their musical talent.

We are only on Chapter 14 now. But we are thoroughly enjoying our journey.

Also we loved the recent episode on birds. We live part time on a boat in a marina and springtime can be very loud, crazy and messy because of the seagulls. Now we know what all the fuss is about. It’s still annoying but we can watch their mating dances, and hear their incessant squeaking with a deeper understanding.

Kevin Kalikow

Apr 22 2025 at 10:34am

Russ,

First, thanks for, as usual, an informative discussion.

Second, I apologize for barging into someone’s affectionate memories of their father, but the song by Diane Renay was Navy Blue, not Sailor Blue.

Kevin Kalikow