| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: July 22, 2015.] Russ: Now, your book weaves together a lot of fascinating stories about the role of government, environmentalism, the idea of wilderness, community, where our food comes from, and so on. But at the heart of the book is a dispute over whether an oyster company was going to be allowed to operate in the middle of the Point Reyes National Seashore on the coast of California north of San Francisco. So I want to start by talking about the place where that story takes place--the area known as Point Reyes and the national seashore. Where is it, and what is your personal experience of the place? Guest: Absolutely. Well, as you said, Point Reyes National Seashore is north of San Francisco on the coast there, and it's about 100 square miles of rolling hills and open pastureland and forests and ridges and beautiful beaches. And I grew up out there. I was born in the Bay Area and from about the age of 4, grew up in West Marin, which is a community of [?] small unincorporated towns out in that area. So, I grew up right next to Point Reyes National Seashore, and was outside in it a lot, camping and going to the beach and hanging out in nature a lot. Russ: It's an extraordinary physically beautiful place. Guest: Oh, yes. It's gorgeous. And there was just an article I saw recently that was the top 10 or 20 most beautiful unknown places in California, and the top 2 were both in Point Reyes. So it's a great, beautiful place--natural beauty; but the communities near to it are really interesting and wonderful, too. There's a number of little towns that have become more popular recently with tourists as well. Great food community, great agricultural community, too. Russ: Now that we've talked about it on EconTalk of course it's going to be a lot more crowded and less unknown. Guest: Sure. Well, I actually--I don't remember where it was but there was an article about how actually Bodega was a cool place, and Point Reyes had already become so cool that it was a bit passé--you know something like really trendy when there's the pushback a little bit. Russ: Fer sure. Guest: People definitely [?]. Russ: Now, try to give, for those who haven't been there, and if you haven't been there, it's a beautiful place. But I have to add: there are many beautiful places north of San Francisco and south of San Francisco along the coast that are similar in landscape and in breathtaking beauty. But this is a little less disturbed than some of those. It's a little different. And it's a little more disturbed in some ways, with human contact. So try to give people a feel for what it looks like. It's not just a seashore. There's stuff going on nearby, and up to the coast--there's this unusual mix of human activity. Guest: Absolutely. Well, what makes it so fascinating, I think, is it does have that mix of proximity and remoteness. It's about an hour's drive from San Francisco with decent traffic. So, very accessible. But it does feel very remote, and it gets millions of visitors a year but it never, it rarely feels crowded. I won't say 'never' but I've never got that sense. Maybe right near the parking lot at one of the beaches at the high day[?] during the summer. But historically it's been a working landscape for a long time so that it's a very interesting mix of uses; so about a third of the park is taken up with working farmland, or I should say pastureland called the Pastoral Zone, and there are working dairy farms and cattle ranches there. There was also a Coast Guard station. Russ: A picturesque lighthouse. Guest: Yes, of course, of course, a picturesque lighthouse. And so there's decades, over a hundred years of that, in that regard, too. Russ: So, in some sense, with the ranches and dairy farming that goes on there, it's an unusual place because part of it is very wild and part of it is less so. Guest: Yes. It happened very quickly, too, what's interesting about the landscape is you have a lot of different types of landscape within a relatively small area in terms of rocky cliffs and beautiful moors that look like something out of Wuthering Heights, something like that; and then you have these very dense forests. So, yes, it does change a lot. And there's that mix of agriculture and wilderness even literally right next to each other. |

| 6:00 | Russ: Now, one of the great things about your book is you learn a lot about oysters, and oyster farming, which I had no concept of. Most people know what an oyster is. I learned that an oyster has no brain, but does have a heart. And I learned how they are farmed, which is seemingly impossible. So try to give us an idea of the history of oyster farming, which is not most people have much knowledge of. It's called 'mariculture,' if I have that correct. Guest: That's correct. 'Mar' is from the word for sea. So, for a while in the United States, oysters were more of a harvested food than a farmed food. Some of the earliest European settlers, the Dutch coming here found billions of oysters ringing all of the islands--the New York Harbor. And so they were very plentiful, and for a long time, as I said, mostly a harvest operation. But oyster mariculture was born when people realized that, okay, you took young oysters from this place and moved them to somewhere else, slightly different water quality, they would do better. Or they would grow faster. Maybe one place was very beneficial for oyster spawning--breeding and hatching--but they were more flavorful somewhere else. And so they would have that combination of the oyster while making it not as drastic as moving their whole location but maybe moving oysters around a little bit within a smaller area. Or, starting them out as little oysters in bags and then leaving them on a more open, in a more open area to mature. So there's a lot of different techniques, and what I found fascinating talking to different oyster farms and different oyster farmers even within the same bay they all had their sort of different special techniques. Which was interesting. Russ: Well, the part that was extraordinary to me was that there aren't any oysters particularly native to the San Francisco Bay area. And they-- Guest: Not-- Russ: And in the early days of oyster eating in the aftermath of the Gold Rush came from people shipping oysters in barrels across the country and growing them. So talk about how they did that. That's crazy. It's bizarre. It's unbelievable. Guest: Yeah. That was fascinating to me, and it went against everything I had heard about oyster history in the Bay Area. And I had no idea I was going to encounter that. I marched it over to the U.C. Berkeley Bancroft Library to do my 19th century oyster research, and I found all these accounts of this man named John Stillwell Morgan, who was the principal[?] oyster pioneer, really, on the West Coast. And he came out from New York; he was from Staten Island. And he was sent out by one of New York's biggest oyster barons, with gear and funding to go right in 1949, with the first rush of '49ers, the Gold Rush, to look for oysters. And he didn't find any. And that's what surprised me, since I'd always heard that there were plentiful native oysters in the San Francisco Bay. But he looked everywhere; he didn't see them. And so he spent about 20 years working on shipping them down from Washington Territory. Because a couple of years into his search in the San Francisco Bay area, he found out that they were up there in a place of [?] water bay and is Willapa Bay now. And so he spent, yeah, about 2 decades trying to get the Washington oysters to establish in the bay. And some crops would work, but not a lot. They were very small. And it was just what would work. And then in 1869, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, they started shipping out oysters from New York and New Jersey in barrels. And that's when his empire, just, you know, really took off. Russ: And he realized--and this is the part--it's a combination of brilliant and shocking--he realized he could ship a lot more by bringing them as babies, infant oysters, whatever you want to call them--oysterettes-- Guest: Yeah. Yeah [?]-- Russ: and then maturing them in the water of around San Francisco. Right? Guest: Right. And the interesting thing about the oysters, as I mentioned, with the development of oyster mariculture, is that where the oysters grow up matters a lot for how they--everything. Their texture, their taste. So, he first is shipping them out as grown oysters, as was normally done. And then he realized it was too expensive, with the freight. So, he shipped them out a bit smaller, and then he thought, 'Well, you know, we got'--I don't remember what the percentage is off the top of my head right now, but, you know, it's okay--'so 70% survives. That's not bad. Let's see if we can get them out even younger.' And the freight was the same for the barrel. So, I think instead of like 600 oysters per barrel he would get 20,000 or something. And it fascinates me to read about it, because he was interviewed by Bancroft[?] about being this titan of industry, and it was a very big deal in industry hatred[?] the fact that he did this. And there are all these, you know, notes in the archives about how he couldn't publish that detail. And so there's this interview--the sort of result of this interview ended up in a book about prominent businessmen in San Francisco at that time, and that's not in the book. Russ: And once he got the babies out, the little oysters out here, what did he do? How do you-- Talk about a modern oyster farm in the Bay area. What are they doing? Guest: Sure. Absolutely. Well, it's not that different, in a way. You get the little baby oysters, and you, they are called [?]. And so they'll be a bunch of little tiny baby oysters will adhere to an adult oyster shell or some kind of a shell of another shellfish. And then you put them in the water and wait for them to grow. And different species of oysters grow different rates. As I wrote about it in the book, I went out and toured some of the beds at Drake Bay Oyster Farms. And those oysters took about 18 months, 2 years, depending, maybe less, to mature to full size with the [?] itself. Russ: But in modern times, they are not shipping them on railcars across from New York. Guest: No, no. Russ: So what do they do? Where are they getting the little ones from? Guest: Sure. Well, different oyster farms do different things. Many--so the majority of the oysters grown in California are the Pacific Oyster, which is named after Japan. And so in the early days, those were coming in shipments from Japan. But now they breed them--some farms in California breed them, they have them in Oregon. So if they try to breed, you know, their first spawn, their own, new oysters, but it doesn't work out or there is an issue with the water and they all die, they can, you know, order them from another farm and they'll get a shipment. I don't think they come in big wooden barrels any more. But similar to marketing[?] today. So maybe you [?] somewhere else or [?] on their own. Russ: And, this is a stupid question, but you don't have to feed 'em. Guest: No, well, that's the thing. Well, you have to put them in water, and it has their food already in it. Which is algae. Make sure that the water is the kind that they will like, that has enough algae for them, can fatten up, but not too much that they choke. Russ: And the last, I think, fact to get straight before we move to some of the controversies: When we talk about the Drakes Bay Oyster Company, which is where the dispute--the company that gets involved in the dispute, which is located in the Point Reyes National Seashore--there's no--this is just so bizarre. There's no place for them to adhere to. There's no rocky bottom. Guest: Right. Russ: So, they are suspended on strings? Is that correct? Do I have that right? Guest: Yes. Russ: How do they do that? Guest: So, the oysters--they don't have a foot like [?] like a mussel--mussels have a--I can't remember the name-- Russ: A thingy. Guest: Yeah, a thingy. Exactly. But oyster shells will adhere pretty solidly to something hard, and that's how they stay. And then over time, oysteries build up where the old, deceased oysters kind of become part of the hard substrate that the new oysters can adhere to. So, baby oysters will, when they are firstborn they are mobile and they kind of swim around in the water. And then their exterior will start to calcify. And so once that happens they will kind of settle onto the bottom or settle onto some hard surface. And then catch and grow there. And they will stay growing there unless you take them off and move them. So, at some oyster farms, they start with the little [?] larva, and they'll have them attach to either pieces of shell or other oysters. Or I've seen them do it with rods, like a long [?] or metal rod that ends. The baby oysters will all adhere to that and start to grow. And then when they get a bit bigger, they chip them off without harming them. And then they can move them somewhere else. And so they can put them in a bag, so they are more mobile in the water so they can put them in one part of the bay and they can grow for a while there; and then they can move them to somewhere else. I hope that makes sense. |

| 16:32 | Russ: Yeah, but I think the last piece to understand is that the action in this story takes place in what's called Drakes--I don't know how to pronounce it--is it es'-te-ro? Or es-te'-ro? Guest: Join the club. I always say es-te'ro, but I've heard both. Russ: So, I'm going to follow you. So, Drakes Estero is an estuary, an inlet from inside Drakes Bay. Drakes Bay is a massive, massive sheltered bay, almost like an inverted Cape Cod. You can find that on a map, folks. And then, inside, up the estuary, is where the oysters are growing, because that way you don't have storms and things that are going to take all your stock and send them [?]. You can find them in the morning, when you need 'em. When you need to pick them. Right? Guest: Right. Yes. And I guess for people to visualize: Drakes Estero--I can't even [?] Russ: No, it's tricky. Guest: The estuary, it's sort of shaped liked a walking brinkley glove[?] a little bit. In the sense that it's got five main sort of fingers that reach out into the land. I heard somebody say it looked like a chicken foot. But I'm going to go with glove. So, that's sort of the shape of it. And it is sheltered. And oysters are often grown in estuaries or in bays or in where a river feeds in. They like brackish water. And when there is a little bit of fresh water getting in to the oysters they'll have a sweeter taste to a lot of people, like? So that's the best environment for oyster growing. |

| 18:18 | Russ: So, now, let's move to the controversy. Guest: Okay, Russ: On the surface, this is a very small story. It's about 31 workers, living in, many of them living in not fancy shacks or cabins or-- Guest: Yeah, very modest. Russ: Near the water. Growing these oysters. Harvesting these oysters. Very small operation. It's hard to imagine that this is going to become a national story that is going to get people really riled up. But it does. And that is a good chunk of the book. So, try to give us a thumbnail of what the fight was about. And what happened. And it's a thumbnail, because obviously we could spend the rest of time just on this. But give us just the overview. Guest: Well, the basic--the thing to overview is that, um, there was an oyster farm in the estuary, on and off since the 1930s, with different ownership, but one ownership from the 1950s until 2004. And then a cattle rancher from next door bought the oyster farm. And the National Park Service said that the lease[?] would be terminating in 2012. And the new owners did not want the lease to terminate. And so there was a big battle over that, and if they could expand it and why they would or why they wouldn't and whether the farm was harming the estuary or not, or benefitting the estuary or not. And since the reasoning for evicting the oyster farm was that the area wasn't just in a national park but a wilderness area, there was a question of" What is wilderness? And What belongs in wilderness? And what does that really mean? Russ: Yeah, I want to talk about that. But one detail we've got to mention is that, between the establishment of this farm in the 1930s--1962 is the time when the point raised, National Seashore Act, gets in place. Guest: Yeah. Russ: I'm going to read the line that you quote in there. It says, "The government may not acquire land in the pastoral zone"--which you mention before, where the dairy farmers are, and the ranchers--"the government may not acquire land in the pastoral zone without the consent of the owners so long as it remains in its natural state or is used exclusively for ranching and dairying purposes." Guest: Yes. Russ: And of course that description, grandfathered in, essentially, the farmers in the area, if they were farming--cows. But it left unspecified oysters, except that at some point it said that oyster: When do we get the key statement that the lease expires in 2012, the opportunity to use that land? Guest: Sure. Absolutely. Well, and in the past that you are referring to is talking about a time when they were talking about property condemnation. And so these, the land owners, the different ranching families, like, as I write about in the book--there was a question about whether they were just going to be informed, 'Hey, here's some money; you have to move', based on government appraisals. Russ: The equivalent of eminent domain. Guest: Exactly. And so it was decided that they couldn't do that; that the ranchers had to convect[?]. So, and they did. So, the ranchers decided that they would sell their land to the government. And that was all getting worked out in the 1960s. And then in 19--so the parks created, in 1962. And the oyster farm that was in existence was called the Johnson Oyster Company. And he only had a few acres. So, you know, these ranching guys had hundreds of acres and lots of lands, really valuable lands; and Charlie Johnson just had a few, next to the estuary. Because he didn't own the estuary, he just had, you know, he just [?] farm oysters there. So he sold, in 1972. At that time he signed a lease which had a paragraph that said--gosh, words, where's the language, I'm sure I have it here somewhere-- Russ: It's okay[?] Guest: It's okay. But basically that it may be renewed; and that was a 40-year lease. So, 2012. So, it could be renewed, depending part policies in place at the time. Basically. And that it was a terminable lease; but that they couldn't terminate it without compensation[?] basically. So, that happened in 1972. And then, but 4 years later, the Point Reyes Wilderness Act happens. And it designated 33,000 acres of the park to be wilderness area. Which has different restrictions than just a national park. So, that sort of where the tricky part came in for a lot of people, is where it's relatively common to have commerce and private business and agriculture in a park; wilderness area is sort of a different story. And a lot of people had very different opinions about how that should get worked out. Russ: But in many ways, that's a legal question about what the rules of the game are, once the government designates it as a wilderness--reasonable people can argue about whether this plot of land or that plot of land should be wilderness or not, run by the government or not, etc. Guest: Right. Russ: But I think what's fascinating to me about this case--and you reflect on it often as you write about it--and you write about it very eloquently. What's fascinating about the case is that, on the surface, that's a reasonable argument. You know: Should we have wilderness areas? Who should administer them? What should be the rules within them? Those are interesting policy questions; people disagree about them; that's fine. That isn't what this turned out to be about in the public sphere. In the public sphere, this--the way I read your book, and I want to get to get your reaction to this: In the public sphere the debate was about whether this was fair. Guest: Yeah. Russ: Because poor Mister--so, you said, 'In 1972 Mr. Johnson signs a deal with the Federal government that says he has use of the land for 40 years, to farm oysters.' And after that, the lease runs out; it may not; it may be renewed. In the meanwhile, it gets declared a wilderness, which means it's probably not going to be renewed. And he runs out of money, or doesn't want to do this any more. And in 2004 he sells it to another key player, which is Kevin--how do you pronounce his name? Guest: Lunny. Russ: So, the Lunnys own this farm. They rename it the Drake Bay Oyster Company. And that's Sir Francis Drake, by the way--that's who that area is named after--a beautiful story, you talk about it; it's really nice--about the Golden Hind being anchored offshore. I really liked that. So, Kevin Lunny buys this property with the knowledge that he really only has a guarantee of 8 years. Guest: Right. Russ: And I guess what the dispute is about--and I think people who might disagree with your book--you claim otherwise. But the dispute is about: Is that the case? Is it-- Guest: Right. Russ: In other words, if I say to you, you are buying this from me and I'm going to tell you, you've only got it for 8 years. Okay, well, that's life. Maybe it will be renewed. Maybe it won't be. But you suggest that, time and time again, when Lunny tried to see if it could be renewed, the government said: No. You can disagree with that or not; you can argue if it should have been renewed; you can argue that it shouldn't be wilderness. But there's no deception. And I think what--when this reached a level of controversy, what happened is that people felt that Lunny had been treated unfairly. And yet, I would say your bottom line is: Nah, he just didn't get what he wanted. Guest: It's so hard, because, you know, I was just--I was just looking at some photographs of the oyster farm[?] the other day, and it was such an emotional issue, and I really feel for everybody that was involved. I know that they care so much about the farm and all the workers, who, while Drake Bay Oyster Company only was concerning[?] in 2005, many people who worked there for decades. So, yeah, I mean, I feel like it's kind of [?] to say they didn't get what they wanted. I think it's just that their vision of what was possible wasn't really in line with what they were being told. Russ: And they didn't want to hear it. Guest: Yeah. Right. Yeah. That was one of the biggest shocks for me in my research, because I had the impression that there was something more solid there, in terms of what they had to work with. That there had been some promise of renewal or suggestion of renewal or something. And I've really tried to find it. I really did. And I just couldn't find anything. And I appealed to Drake Bay; I appealed to their legal team. And pretty much anyone I could think of. But I couldn't find anything. |

| 27:49 | Russ: So, that's the negative on the Lunny side. The negative on the government side, again, as the reader of your book is the following: At various times in this debate over whether the government should give them a lease extending past 2012, it appears that government science was either in error or strategically manipulated to make the case that oysters weren't good for the bay. Guest: Right. Russ: Oysters weren't good for the environment. Oysters were damaging the wilderness. And I think it's a sobering account no matter which side of the political debate you are on, whether you are worried about the encroachment of humanity into wilderness areas or vice versa: you are worried that government is too restrictive about the uses of private property in various settings. Neither side comes across so attractively in the book, to be honest. Is that a fair reading? Guest: I think so. That was my impression, that I feel that I, you know, I understood or I tried a lot, I tried very hard to understand the motives of everyone involved and to try to put myself in somebody else's shoes and to be empathetic. But yeah, I would agree with that characterization, that neither--nobody came out of this without any mud on their shoes, I guess, is a way to put it. Russ: Very appropriate for an oyster story. Guest: Right. Exactly. Russ: So, I'm going to read a quote from the book, which I think is very--adds another dimension we haven't talked about. And you can elaborate on it. Here's the quote:The oyster feud was a strange political dispute in that both sides seemed to be liberal Democrats--liberal Democrats who supported organic sustainable farming on the one side, and liberal Democrats who supported wilderness on the other. Many said that they supported both, but had to come down on a particular side for one reason or another. And of course, there were other, there were side issues about, again, how much wilderness there should be and what should be the human footprint, etc., etc. But one of the fascinating aspects of the story is that it was a dispute between the romance of local food, which is what oysters were providing to local restaurants, versus people who wanted to hike into a pristine place. Guest: Yeah. Or, kayak, I guess, in this water. But yes. No, that's true. And I think that may be part of why it got a lot of attention. I think there are a number of reasons why it got that kind of attention. But I think that was one, that people were confused by, you know, somebody that would normally look at a dispute and say, 'Okay, so the Sierra Club is on this side of this dispute, and I like the Sierra Club, so I'm going to be on that side, too.' But then they'd look and see that Michael Pollan, the food writer, was on the other side. And that would be confusing: 'Wait a minute. These are all people whose values align with mine.' So, what is it about this case that's splitting it? And so I think that was something that was unusual for a lot of people around the Bay Area, anyway, is that it sort of--it was confusing in that sense. It wasn't easy for people to figure out who to support. Russ: Who to root for. Very consistent with the economics central idea--one of the central ideas of economics: There are no solutions, only tradeoffs. And here it was a case where the costs--somebody was going to have to pay a cost. It just was a question of who. And there's no easy answer, I think. People who wanted to [?] "right side." Guest: Right. Right. And it wasn't entirely liberal Democrats, too. I mean, you know, I believe the Drakes Bay Company honors, identify as Republican, and there were others. I don't want to oversimplify in it that there were only Democrats involved. Russ: No, but we know what you meant. Guest: Exactly. Yes. That was an unusual--I don't know if it was that unusual, but something that was of note to some reporters. Russ: And I guess, it gets very ugly, in parts. Friendships I'm sure get ruined and ended over this dispute. I found it interesting that as far as I know, nobody gets killed. Guest: Yes. Russ: The only shooting that takes place is with a camera, which is an embarrassing episode in the book that you recount. Somebody trying to videotape surreptitious activity or inappropriate activity by the oyster boats; and its effect on seals. Yeah--that's an amusing comedy of errors really. Guest: Yeah. Russ: But this is the kind of a dispute in a different part of the country I think people would have been killed. But at least there are no deaths here. Guest: Yeah. Thank goodness. When I was--[?]--when I was thinking of writing this book and speaking to people about it and publishing companies said, 'Well, nobody's been killed yet but there's still time,' and I'm like, 'Don't say that; it's horrible.' But no, I mean that I had reporters say to me, before this wrapped up, that they expected militia groups to show up and that guns would come out. And I think--I think you are right. Had it been somewhere else, that may have happened. I think they were referencing the Bundy Ranch situation. Russ: The Marin area is not known for its hunters. Which--the gun ownership in that part of the country is relatively low compared to others. Guest: It is. There's a real stigma, I think, for a large amount of the population of the Bay Area, which I talk about in the book, as you know. |

| 33:40 | Russ: So, let's just finish the story and then we'll talk a little bit about the consequences. So the end of the story is that 2012 comes along; the permit is not extended. And the Lunnys go to court. What happens then? Guest: Yes. So they sue the Federal government. In a nutshell, basically just accusing them of capricious action. But they are denied. And they try to take it to the Supreme Court. And that is ultimately also not taken up. So they lose their battle. And there is a settlement about what they need to do to clean up. And come--[?]--but at the end of 2014, they had to leave. And so they closed down the farm, and it is no more. And now the Park is working to clean up the area where the farm was. Russ: And some of the oysters were not harvested, I assume. They were-- Guest: Yeah, they were [?] planting-- Russ: you talk about that. Guest: to a late date. I don't know when the last planting was. I think it was at a very--it's really incredible obstinance on the part of Drakes Bay to keep planting. Their conviction was really something to be admired in a lot of ways. Because they just definitely felt like they were in the right and they were going to keep fighting until they got what they wanted. But, so, the oysters were planting pretty late in the game, so there were a lot of oysters that went to waste. And a lot of which were still in the estuary at the time the farm moved out. And there's probably still some out there. But [?] that shouldn't be [?] I don't know. They may have gotten involved by now. There were many, many still there. Russ: Did they have any predators, by the way? They must. Guest: Oysters? Russ: Yeah. Who eats oysters? Besides us. Guest: Yeah. Besides us. Raccoons eat oysters. Russ: Otters? Guest: Pardon? Russ: Do otters eat oysters? I feel like they do. Guest: Otters probably do. There aren't many sea otters around Drakes Bay. And I don't think there are river otters in the estuary, although they are returning to the area, and some sea otters, too. But stingrays actually tended to be the biggest predator, or the biggest problematic predator for oyster farmers in the Bay area--stingrays would get them. And oyster drills, which aren't native to the area but were introduced with the shipments in the 19th century. Russ: The idea of encountering a stingray in one of the fingers of that glove is a pretty frightening thought. Shallow water. Guest: Yeah; there's fewer of them. There's great stories of some of the old timers in West Marin of--they would set up fences to keep the stingrays out from around oysters in different shellfish that they were growing in the area. |

| 36:45 | Russ: Let's talk about wilderness. You have a lot of thoughtful things to say about it. One of the fascinating aspects of course as you put it at one point: It's a lovely idea that many people care about deeply, that the land should be returned to its wild state. But as you ask: Wildness as off when? Guest: Right. Russ: Talk about the Native American population and their role in that. Guest: Sure. There was a number of different native tribes living in the Bay Area prior to the arrival of Europeans. It's been said that actually it was one of the most populous areas in the Americas outside of the Aztec cities. I wasn't able to confirm that, but it's an interesting thought. And considering how temperate the area was, I wouldn't be surprised. So, there's a number of tribes living there, and from everything I've read and heard, they were very involved in managing the landscape and even managing animal populations to a degree. They hunted the tule elk, and they would burn areas of brush to increase pastureland for the elk and the elk liked to eat the fresh, young plants that grow after a controlled burn. So, they had a very intimate relationship with the land. So, the native population managed the land very closely, as I said. But there was a lot of changes that happened as soon as the Europeans arrived, as I [?], and many of the grasses that you see in general and in the Bay Area are not native grasses. Even these iconic grasses that you see that turn golden color in the summer, they weren't there 300 years ago. This is Mediterranean grass that came with the Spanish cattle and later with other animals. So, there's just been a lot of change. Obviously there used to be bears and all kinds of different predators. They have moved out. Tule elk were absent from the [?] area for about a hundred years before being reintroduced. So a lot changed. So basically when you are talking about a wild place or an original wild place it's interesting because an ecosystem is always in flux. People talk about the balance in the ecosystem, but actually all species, plants and animals, all of these vie for survival and ascendency to a degree. And if any one could become more productive and more successful, even to a detrimental degree, they would do so. There's not a lot of awareness on the part of a tule elk that it's going to eat out [?] of its own habitat. There was recently a population crash in the elk out in Point Reyes, actually, probably because of the drought. Things change over time. It is an interesting question of how far 200[?] Ridge Knoll wilderness can you get, and what does that really mean, and does it matter? And what about wilderness matters? And I think that that serves[?] the question that's in [?] now: What is the core of wilderness, so that we can preserve it and figure out what belongs there and what doesn't? Russ: What's interesting to me--and by the way, we did an episode on this issue of balance of nature with Daniel Botkin ages ago on EconTalk--2007--and we'll put a link up to it. Because I do think we have a certain false image of nature's equilibria, and it's good to keep the truth in mind, I think. But we have a romance about wildness and wilderness that is in some sense inherently impossible to implement. And as a person who loves that golden grass--and I've taken hundreds and hundreds of photographs of that landscape in different light in the Stimson Beach, Mount Tamalpais area, Muir Beach, all up and down the coast. I love that landscape; I think it's absolutely gorgeous. And now you've ruined it for me. Guest: So sorry. Russ: You've told me it came with Spanish cows defecating seeds from-- Guest: Well, it's not all non-native yet. A lot of it-- Russ: So, what I was going to say is, there's actually something very beautiful about that: that the human desire for exploration has made its mark on that landscape and brought something wild, or not so, whatever you want to call it, from the Mediterranean, all the way, thousands and thousands of miles. Maybe I'll appreciate it even more now. Guest: No, no. Russ: But it does make the point that attempts to recreate the Garden of Eden are in many ways a fool's game and really a form, to me, of self-deception. We want our wilderness, and that could be a white person's explorer wilderness from 1500 or a native American wilderness from a different time; and we should be honest and realistic about it. Guest: Right. I have very romantic sensibilities, which I'm sure is apparent in the book. Russ: Yup. They were enjoyable. Loved that part. Guest: But even so, I think when it comes to thinking about wilderness, I think I am more of a realist, or at least a functionalist rather than a romantic, in that I think what matters--it matters less the technicality of native or non-native or how long something has been there or not. That's why I think I write that one of the central issues of this story across the board was one of belonging--of what belongs where and who and why and who decides. And that can be an oyster farm or a kind of grass. And sometimes something is just too late. The California grasslands have reached a new equilibrium. They have their own system going. So nobody's going to go and rip up all of the non-native oat grasses in California now. I haven't heard anyone that wants to. So you kind of have to--sometimes when somebody says, 'Well, just because something's not native, we should take it out.' There's foxglove growing in Point Reyes National Seashore which are not native. And I happen to like that flower a lot. Somebody might make an argument that because it's non-native it doesn't belong there. But you could also say, 'Well, it's not hurting anyone. And it's growing right next to grass that's definitely not native. And I live near there and I'm not native to this part of the world--I am, but not ethnically, so-- Russ: [?] |

| 43:52 | Russ: I'm going to use an image I've used probably way too much in the last few episodes. I hope listeners aren't tired of it. We talked, going back a few episodes ago and have revisited this idea that it's hard to create a prairie. You might know what is in a prairie, but you can't just take all the ingredients and plant them all and get a prairie. Certain things will dominate at the wrong pace and you end up with something very different. And I think the implication of that example for this story is that if you eliminated the non-native grasses, you are not going to be able necessarily to recreate what California looked like 10,000 years ago, or even 500 years ago, or 600 years ago, when Drake showed up, because you don't have the right recipe. You don't know how to get there from here. And so inherently you have to be doing something that's partial, that's imperfect, that has to accept the fact that we can't go back to that Garden of Eden, whenever you want to date it. Guest: Sure. And sometimes, I mean, people do experiment with either re-wilding or with native plant restoration that are successful. So it kind of depends on the instance and the scale, too; and I think there's sort of room for both. And I think what's interesting about when you have scientists working in a space whether it's a national park or what have you, I think I mentioned in Point Reyes there was all this European beach grass, continental beach grass growing, and there's an area that they pulled out large tracts of it; and a lot of local people kind of just rolled their eyes and said, 'Why? What's the point? It looks nice. We're used to it. It's been there for over a hundred years. Leave it be.' But when I did go out and see the spot that they had done this restoration in, it was really interesting, because all these little plant ecosystems had grown back. So--again, you're not going to go and re-landscape all of California. But it is interesting to see little bits. I can talk for hours about all this stuff, so don't get me started on rewilding. Russ: I'm going to mention one other thing, though, because I think it's important. Which is that the government responds to political pressure. It responds to the voices of voters, of lobbyists, of money, in all kinds of complicated ways. And so even if you and I were very into rewilding and thought that the right way to keep the tule elk population when it was too large, the right way to limit it is to reintroduce bears into the area, the political forces are just not going to allow that. It took about a hundred--I think I've got this right--a hundred years or so to reintroduce wolves back into Yellowstone. They have been removed, really for political reasons, because people were scared of them. They were decimating[?] not dead so many but they kept the elk population down, and people like looking at elk. It gives them a sense of wilderness that's safe. And so I've always hated that Yellowstone was something of an amusement park masquerading as a wilderness, and I'm glad that the wolves are back. And maybe we should introduce bears back into Point Reyes. But it's unlikely to happen. Just for political reasons. Guest: I think the ranchers would have a problem with that. Russ: Yes they would. Guest: They have complaints of the elk. I think that grizzly bears--they'd probably have a little to say with the cows. But that's not the only reasons. Yeah, that's the tricky thing when so much of the world is tamed that the parts we preserve should be wild, or "wild"--it's not so easy. You can't just say, 'Grizzly bears, get over there and do your thing and that's it.' And that's like the nature of something being wild, is it doesn't work like that. So, hence there's all kinds of fascinating conflicts that brings up. Russ: And there's a population challenge: you can't have 3 of them; you probably need 30. And when you have 30, they are going to do things you don't like. Guest: Yeah. Then you have prey animals, though, that have evolved to be very productive because they were everybody's food. So there've been a lot of issues with the tule elk and other types of large game in Point Reyes in over-population because there's no predators; there's no hunting. So, what do you do? Russ: And every once in a while we have a sanctioned hunt where a bunch of them get killed, just to try to limit those impacts, right? Guest: In places, yeah. In Point Reyes, that is still an unsolved question. Russ: What you write about the deer in there, which is another ungulate of the region for a long time is really very beautiful and I--I encourage people to read the book for a lot of reasons, but one of them is to read about the white deer. It's really special. |

| 48:08 | Russ: I want to talk about the elusive nature of truth. Guest: Okay. Russ: You came into this--I want to hear your perspectives, and I'll give you mine as a reader of your book. So, you came into this somewhat sympathetic to the Drake Bay Oyster Company--at least, that's what you say. And you spend way too many hours trying to figure out what really happened and who said what and it's a detective novel in some dimension. And you come to a conclusion. And I suspect--and you come across as incredibly reasonable, as a truth-seeker. It's inspiring in many ways. And yet I assume there are going to be a lot of people who are going to hate your book. And they are going to say, 'Oh, she missed the story. She lied. She slanted it toward the Park Service, toward the whatever, the environmental story.' What are your thoughts on that? Guest: Well, I certainly didn't lie. If I put anything in there that doesn't turn out to be true, then we'll just correct it. I put all my sources; and there is a bibliography at the end of the book. And I did my best to fact check; and someone else fact checked. So, we did what we could. You know, this story was huge. And there were so many worm holes to fall into. And towards the end when I was writing this, I read this book by Eula Biss called On Immunity. Which is another controversial topic about vaccination and different things. But at one point she writes about in her brief search she felt like Alice in Wonderland falling through this shaft of like books on all sides, more than she could ever read. And one person--she finds different sources--this is not Alice in Wonderland but this is appropriate for a 10-year-old, but one source says 'Drink me' and another says 'Eat me' and another says this. And you know, after a point when there are so many different perspectives--and this is, I think what I say is I had to say, 'Okay, this is the best I can do for the time that I allotted to this story.' And everything else, I have to just walk away. And I do feel confident that I got the core of the story right. I know people will disagree with me. Especially about the science stuff. And there's parts that I could have added 4 extra chapters on. Russ: I think you made the right choice there. Guest: Yeah. It's a book I didn't want it to be too long. It's not an encyclopedia. And I think especially people that were insiders to that will surely be outraged over one thing or another, just in the sense that, 'Oh, she didn't write about this part of the story. She didn't write about this.' And I do say that. I say there's lots that I left out. There's things that I left out that would have made both sides look better. And worse. But in the end I tried to be fair and representative. And it isn't a secret. And in the end, I did not get a final interview with the Drake [?] people that I wanted. They didn't respond to any of my requests at the end. If anything is missing it is that piece, because I would have liked to get a more individualized take. What I had to settle for was what they said in the public record, other media, and they were very vocal about it. Russ: Well, that's life. I didn't mean to accuse you of dishonesty. Guest: No, no! It's okay. Most people [?]-- Russ: They will. But what I meant was that this is such a complicated story, and to do a beautiful job giving it a narrative arc inevitably, as you say, you have to leave some things out that might have shaded one's feelings as a reader toward one side or the other. And yet, what you gave to me as a reader was enough to make what appears to be a decision about the fairness of it. Again, whether it's good public policy or not is a whole separate question; that's not what the book is about. We all have preferences on that. And mine, by the way, are sympathetic to the idea that although I wish there were private wilderness--and there is some--national parks are one of the few things that governments do that I happen to at least enjoy and feel I'm getting some of my money's worth. So for me, as a big private property guy, I'm okay with the fact that these people didn't get to use this land. Maybe it would have been better. It's hard to know--if it's really not damaging anything. But I really don't have any romance about oystering on Drakes Bay. So, to me this is just a non--I can't get outraged about it. But partly it's because I read about it from you. So I'm wondering if I read about it--I read some other stories about it preparing for the interview. But I'm wondering: Could somebody have constructed a narrative that had a different emotional appeal? It's just an interesting question. It's not a--I don't know if there's an answer. Guest: I think in general for a lot of the other narratives, because the Park employees were not permitted till it was over to talk about their involvement at all, the personal element I think was missing. So, one of the main characters in the book is Sarah Allen, the scientist whose work got called into question. And so I think that I made attempts to talk to everyone involved individually. And so I think that maybe one of the reasons why you get that impression in the book is there's a little bit more of a human [?] aspect [?] side of it that I think you didn't see. It's not just--but I don't know. I think also I have to get some perspective on it. And when you are in the middle of it and you are hanging out with people who are so stressed out about losing their business and they are crying and their children are crying, I mean you just get so wrapped up in it emotionally. And it's hard not to, because this was such a big deal. And I think for a lot of people in the area, it was something, there was something symbolic about it, too. They care about their neighbors and they care about the community. But I think there was this other, sort of, I don't know, sort of subconscious anxiety about encroachment from outsiders, and that the, you know, local people who used the lands were being replaced by tourists who just wanted it for recreation. And so I think there was something to doubt[?] happening to a lot of people: people were being priced out of places that they'd grown up. You know, a lot of rental where normally a young family might live; it was being put on Airbnb instead. And I've never actually heard anyone say this, but I feel like it's not an accident that this dispute became such a big deal at a time when the community was changing so drastically from the one that I grew up in, which was much [?] more committed to, you know, the demographics were changing. I guess. Russ: Well, it's more of a--it's more upscale than it was, to be just simple about it. Guest: Sure. Yeah. And people are getting priced out and [?] just worry about that. Like, I think I used the word 'gentrification' in the book. It's a bit--it's not like an urban neighborhood in the same way, but there's this sense of, you know, people are excited about the [?]. Some people are having very successful businesses because of it. But it's a, you know, it's a two-sided, it's a two-sided thing. So, I mean, you know, I think there's many reasons to be very sympathetic to the oyster farm; but I think what gives me great assistance[?] in the end was just trying to lay out the arguments in its favor and investigate them as best I could. And in the end it seems to me that the correct decision was made, even though it was a difficult one and maybe heart-breaking one for many people. And, yeah. Russ: I wouldn't go that--as someone with a different perspective, I wouldn't know whether it was the right decision. But I didn't think it was an unfair decision. Which is again I think what really motivated so much of the dispute. I have no doubt that private owners of land are often better stewards of that land than bureaucrats, or if you want to make it a little more romantic, Park Rangers. I think there are people who take care of their land and let it revert to wilderness; and I should mention there's a glorious prairie wilderness project going on in the mid-West that I'll put a link up to that is--you know, it's a private conservancy; it's not a government national park. So I'm a big fan of that. It's hard for me to get excited about oystering as a way of stewardship of the land; and it's just not there. It's just--it's just a question of--for me, that's why, as a reader, it came down to fairness. I, like you--I assumed I was going to be sympathetic to the oyster company. By the time the book was over, I felt bad for them, as you do, but I don't think there was an injustice here. And I don't think there's a particularly big policy error, either, while we're at it. But it's a small issue. And I think it's lovely that there are still some dairy farms there. Right? There are still some, right? Guest: Oh, yes. There's--a few have closed over the years but there definitely are still [?] dairy farms still functioning with the same families that owned them a hundred years ago. And one of the positive things to come out of this is the Department of the Interior has expressed a stronger commitment to maintaining those long term, because they also function on leases, and short leases at that--some of them are on just 5-year leases that they are renewing. But they are not in the wilderness area, so it's a different issue. And so I think some of them are getting 20-year leases now. And actually the latest I heard is that Drakes Bay Oyster Company is opening a new oyster farm somewhere else. Russ: Right. There's lots of land nearby that's not in the wilderness part of the area. There are oyster companies around the corner. Guest: Exactly. There's an oyster company--there's another bay a 15-minute drive away and there's, I think at least 3 or 4 companies in that bay. I don't know if there's space for them. I was talking on Twitter with one of their [?] communications work for them over the years and she was saying she couldn't tell me exactly where yet because it wasn't 100% nailed down; but they've ordered a bunch of supplies from China for some new techniques, so they've got stuff in the works. And I actually just found out in the last couple of weeks, so that didn't make it into the book. So it seems there will be a Drakes Bay Oyster Company, just not in Drakes Estero. |

| 1:00:44 | Russ: Let's close with your personal experience. You talk about, you've talked about here the challenges of listening to people cry about what's going on in their lives, and I'm sure it was an incredible experience to write this book and do the research. And if all goes as planned, this interview is coming out the day before your book is to be published. And you're going to get a set of reactions all over again. What are your thoughts on that? I assume some people are going to love your book, and others not so much? And what does that mean for you as someone who wants to go back there, I'm sure, and enjoy that area? Guest: Yeah, I mean, I'm from there. Family members still live there. As I say in the book, my stepdad is one of the librarians in Point Reyes, so I've got roots and family and I'll be back. I think the thing to remember is that there are people in the community that are very vocal about this, and care a lot. Then, there's people that don't care so much at all. And people that somehow magically have not even really heard of it or seen these signs around about it and don't really know what it is and don't really care. So, you talk about the community--they're small but there are a lot of people in the community who have other things going on. So, I'm not worried about the community, per se. With the story, I did my best to tell the truest version of the story that I could, and I wanted it to be a compassionate take on it. That was important to me. And somebody was worried about it being a hit piece. And I hope it doesn't come across that way, because that wasn't my intention with anybody. But I don't know--there are people that aren't going to like it. There are people I interviewed for the book who cooperated and agreed to be interviewed and answered all my questions but still didn't really like that the book was happening, but understood that they had become a part of the story that had national significance and national interest, and has been written about in The New York Times and Harper's and been on CNN (Cable News Network) and Al Jazeera and Fox News, and so it's not a private story any more. And so, I don't know. I have mixed feelings about that because part of me feels strange about telling these stories. But I was careful not to betray, I think, anyone's privacy with things that weren't already out in the public sphere or that they had consented to have. So, I tried to use this book thing honorably. And people aren't going to like it because it's not the version of the story that they would tell personally. But I'd encourage them to tell their version of the story, if that's what they want to do. |

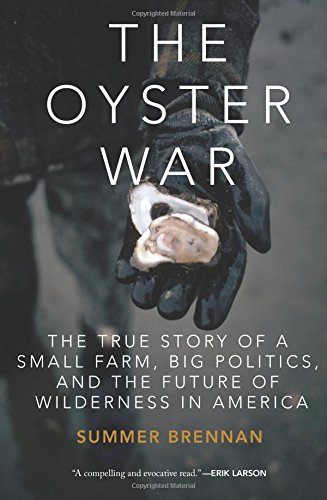

Summer Brennan, author of The Oyster War, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about her book and the fight between the Drakes Bay Oyster Company and the federal government over farming oysters in the Point Reyes National Seashore. Along the way they discuss the economics of oyster farming, the nature of wilderness, and the challenge of land use in national parks and seashores.

Summer Brennan, author of The Oyster War, talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about her book and the fight between the Drakes Bay Oyster Company and the federal government over farming oysters in the Point Reyes National Seashore. Along the way they discuss the economics of oyster farming, the nature of wilderness, and the challenge of land use in national parks and seashores.

READER COMMENTS

Steve

Aug 10 2015 at 3:16pm

Very interesting podcast, as usual. Being located in environmentally progressive California, Drakes Bay Oyster Co. should maybe have changed their approach and registered their operation as a CO2 sink and collected California CO2 credits for the CO2 their oysters pull out of the environment and into their shells for storage. That may have gotten them the political support required for a renewed lease. The oysters would just have been a byproduct of the Drakes Bay Carbon Capture and Storage process. Maybe would have even gotten a DoE grant to expand their whole operation.

The concept isn’t that crazy. There were so many oyster shells deposited in San Francisco Bay over the centuries (primarily on the west side of the Bay between the San Mateo Bridge and the Dumbarton Bridge) that in 1924 a cement manufacturing plant was built in the Port of Redwood City (coincidentally near one of Morgan’s other oyster processing plants) to use primarily oyster beds, over 200,000 tons per year, as a calcium carbonate source instead of limestone in their kilns.

Grayson

Aug 10 2015 at 4:56pm

Thanks again for another great podcast. Here in Colorado, there are all sorts of conflicts over land use, from resource “exploitation” as in Weld County’s fracking operations, other mining and oil and gas operations, environmental demands, to enormous population growth – both in urban and our varied rural areas. Ranchers and growers face economics and aging populations; and our recreational demands, from hiking, hunting, rafting, fishing, climbing, and, of course, world-famous snowsports, draw together a sort of Hobbesian battle of who gets what.

Oh, and California wants the water.

Colorado Open Lands is a non-profit conservation group that buys up lands and holds it in trust, sometimes to help ranchers. Other times to slow development in a key areas. Might be worth talking to sometime.

(I’m not affiliated with them. Just know about it.)

[Link inserted properly. –Econlib Ed.]

steve hardy

Aug 11 2015 at 3:00pm

Not sure what the point of this discussion is.

George

Aug 11 2015 at 7:56pm

I have to admit that I had trouble following this one. Why? Here’s my thought: “the curse of knowledge” is when those who know something and try to explain it don’t appreciate what it’s like not to know. I had the feeling that Russ and the guest knew the story from the book but were taking too long letting the listeners in on the overall framework. A lot of time upfront was spent setting the stage for the story: describing the natural environment and exploring some of the subtleties of oysters & oyster-related issues. However, what I could really have used was, first, an overview at the top of the conversation outlining what the controversy was all about. Then, second, a closer focus on some of the finer points. That way, I would have known how to set the specifics into a bigger picture.

Gregory McIsaac

Aug 12 2015 at 1:44am

Russ Roberts: “…I should mention there’s a glorious prairie wilderness project going on in the mid-West that I’ll put a link up to that…”

The American Prairie Reserve is an interesting and glorious project, but being in Montana, it would not generally be considered to be in the mid-west.

The mid-west generally encompasses the states from Ohio to Kansas and the Dakotas. Western portions of the Dakotas, Nebraska and Kansas and the eastern portions of Montana, Wyoming and Colorado are generally distinguished as the “Great Plains” because of the considerably lower rainfall, very low population densities, greater emphasis on ranching and livestock grazing, and less emphasis on crop production. Where crops are grown in the Great Plains, irrigation is much more common than in the eastern states, and so access to water and water rights is more contentious. East of the Great Plains, there are more conflicts over drainage and the right to get rid of water than about access to water.

The American Prairie Reserve website describes its region as the “High Plains” which I think is a higher elevation region of the Great Plains.

On the topic of private sector wilderness and conservation: The Nature Conservancy owns and manages large tracts of land for conservation. Their web site claims 120 million acres conserved world wide. I don’t think that all 120 million acres is owned by the organization, but some of it is. They use a variety of mechanisms to transfer land into long term conservation, such as purchasing conservation easements. They will also purchase land and give it to a local entity that will take over the long term management.

Greg McIsaac

Dallas Weaver Ph.D.

Aug 13 2015 at 9:08pm

As usual, an excellent presentation. However, knowing something about oysters and their interactions with the environment and the very long history of the fight between the Park Service and this specific oyster farm going back long before it was called Drakes Bay Oyster Company, I found this case a wonderful example of how a bureaucracy can serve itself at the expense of scientific truth. I have no dog in this fight beyond eating some of the best oysters in the world that I discovered in the 60’s as a grad student living in Berkeley. I do have a big beef about faulty, misleading and just plain false advocacy science being passed off as real science. In this case, the National Park Services science is pure advocacy science.

For a quick summary of some of the science issues in this case, see the book review by Dr. Goodman

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/corey-s-goodman/the-oyster-war-a-parallel_b_7977054.html

Dr. Goodman is National Academy of Sciences member so his comments carry more weight than most. He, like the book reviewed in this pod-cast covers the recent fight, not the long history that wasn’t covered in the news.

The history of the fight between the oyster farm and the parks service goes back a lot further than Drakes Bay Oyster Company (DBOC) and to the previous owners who, with his father, go back to the end of WW11. The previous owner, Tom Johnson under the name of Johnsons Oyster Ranch had many previous interactions with the Parks Service. The courts ( I believe one went to the California supreme court which ruled against the Park Service) told the National Park Service, in no uncertain terms, that they were violating state law trying to eliminate all the farm worker housing on the site, without providing viable alternatives. Other cases when to court and Mr. Johnson won all of them. Mr. Johnson didn’t kiss the park services ring and the battle when on and on. The park service tried to prove all sorts of water pollution impacts. As a scientist, I have seen a lot of bad science in my days, but some of the games the Park Service were playing (no controls, improper sampling, etc. etc.) were beyond the pale. I have fired people for such sloppy science.

Considering that diary farms and cattle are about as far as you can get from a “wilderness” and they are a protected class combined with the continual uses of faulty science, one has to conclude that another agenda, beyond wilderness or the environment, is at play. There is an old story about bureaucrats, they don’t get mad, but they do get “even” by destroying anyone they don’t like. This looks like that type of personal fight and the bureaucrats won.

In listening to your discussion, it appeared that the author didn’t really know anything about oysters beyond a very superficial levels. She probably doesn’t really understand any science, so statements like “Given the uncertainty associated with the analysis, the results are not proof of a correlation, but they also do not provide a basis for dismissing such a relationship” would not put up a red flag. This was part of an attempt to support the Park Services science, when it was challenged. As an environmental scientist, this translates into English as we have no proof and you can’t prove our “belief” is not true.

I have been seeing a pattern of too much “true belief” in both science and economics by the government bureaucrats spinning things to confirm their biases. The minimum wage is good for jobs and cormorants don’t eat delta smelt (the 440 Biological Opinion on the delta smelt doesn’t mention the word bird or cormorant).

[broken link html fixed–Econlib Ed.]

Dallas Weaver Ph.D.

Aug 16 2015 at 1:20pm

The more I think about this pod cast, the more I feel the that Russ was successfully spun.

At the end, the author tried to throw a bone to the people destroyed, by saying that the owners could get another lease somewhere else. This author, being California based and also knowing that the California Coastal Commissions was successfully challenged in court for their illegal behavior and had their advocacy science (aka junk science) exposed, should know that it will be impossible to actually get a permit for a new farm.

She knows or should know that her statements about getting permissions for another farm are probably false.

For example, a world famous oyster researcher at USC is trying to get a permit for a FLUPSY (floating upwelling system — floats in the ocean and used for growing very small oysters from 1mm or less to 2 cm and fits in a boat dock) at the research lab at Catalina Island. This little project is smaller than most of the boats in Cat Harbor and will use the same anchoring as the hundreds of boats in the yacht harbor, but has been hung up for a year of pseudo-science nonsense requiring answers to irrelevant and often unanswerable questions. A FLUPSY uses no prepared feed or chemicals and the “concern” by the CCC is that these baby oyster will produce a few gm per day of fecal material from the algae they eat from the water (just like all the mussels, sponges, etc. do, covering all the support structure in the harbor). We have a desalinization project near my house that the CCC and other Ca regulators have held up on permits for 11 year now (no rain yet), again using pseudo-science justifications and models that have been proven false in the scientific literature. Regulators all operate in the gray literature area without “outside” peer review, like you have in scientific journals.

The author also didn’t mention that Drakes bay is the only oyster growing area in the state where the maximum water temperature is low enough to prevent reproduction and the associated loss of flavor (why oysters aren’t as good when they spawned). In all other areas, you need to grow triploid oysters to have good quality during spawning seasons. Triploid = three chromosomes instead of two — a form of genetic modification (GMO) that the eNGO’s consider grandfathered in, because it was before Monsanto and not useful for fund raising.

Russ Roberts

Aug 17 2015 at 11:01am

Dallas Weaver Ph. D.,

You might want to read the book. A good chunk of it is about the bureaucracy’s attempt to use research and science to advance a particular agenda rather than merely seek the truth. That’s what I was alluding to when I said:

Kevin

Aug 24 2015 at 9:50am

I had never heard of this event before I listened to the podcast. It was a little amusing hearing Californians go on about what a big national story it was. I guess not big enough to catch my attention. Whatever happened, given human nature, my guess is the Park Service was really the tool representing more affluent/powerful political forces. That is a bet that will be correct in enough cases thats the outliers will hardly be worth considering, though this may be such a case.

The link to Dr. Goodman posted by Dr. Weaver certainly raises some questions but really the more interesting things are the comments. This is really a fight among leftists. You have people in the comments complaining about government overreach and the problems it poses, people who most likely were enthusiastic about the government taking over all of healthcare nationally. We all like the government when it does what we want. Even Dr. Roberts approves of the National Park because the government is doing what he wants. I also approve of parks, because the government is doing what I want and have little exposure to alternative systems (although I recently went camping on a private park a week after having parked at a state park, and the private was cheaper, and nicer in every way – it was shocking).

Comments are closed.