| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: September 14, 2022.] Russ Roberts: Today is September 14th, 2022, and my guest is Roland Fryer of Harvard University. He was awarded the John Bates Clark Medal in 2015, and is one of the premiere empirical economists of his generation. Roland, welcome to EconTalk. Roland Fryer: Thanks so much for having me. I'm really looking forward to this morning. |

| 0:57 | Russ Roberts: So, let's start. We're going to cover a couple things in our conversation--three things, actually. We're going to talk about your work in education, your work in crime, and then your work as an entrepreneur and a venture that you've been involved in recently. I'm interested in all three. So, let's start with your work in education. You started off--you did something really--you had a crazy idea, which is a very natural idea for an economist and repugnant to most non-economists--which was: Could monetary incentives affect student behavior, teacher behavior, or parent behavior? Fantastically interesting idea, which I'm sure horrified a lot of people. We'll talk about both what you found and the reaction people had. But, let's start with what you found. You started with students, I think. Roland Fryer: Yeah, I started with students. And first, let me just say that for a large part of my career, I have specialized in things that delighted economists and was repulsive for everyone else. So, that's a great way to start this conversation. Russ Roberts: Yeah, yeah. Roland Fryer: It started at P.S. 70 [Public School 70, Max Schoenfeld Elementary School] in the Bronx, actually. I had got into Harvard from--moved here from University of Chicago, where I did kind of a quasi post-doc. My grandmother was just in my ear about making a difference, and that she wasn't interested about how cool my office was. She was interested in whether I knew the janitor's name. Things like that. She was just an amazing woman. And so, really to please her--in the beginning, I wasn't thinking about a cool research project, but just trying to please my grandmother--I called up P.S. 70 in the Bronx. It's a place in the South Bronx where I had spent some time as a kid when I was 11 or 12 years old; and I ordered them pizza. So, every month, the teachers would call me and give me an up or down: Did the students behave, or did they not? And, if they behaved, I ordered pizza--literally me: pick up the phone, order pizza, had it delivered to the students. The kids apparently really liked it. And that's where it started. After that year, the Principal was thrilled, wanted to do it again. And, I happened to meet Joel Klein, who was the Chancellor. I met him here at Harvard. And he said, 'Hey, I heard about this pizza thing you're doing in the South Bronx. Would you like to do it in more schools?' And, I said, 'Well, sure. I'd love to help.' And, he says, 'All right. Well, you come down,' and he introduced me to a bunch of principals. It turns out they were pretty into this. But I said, 'Well, we have to do monetary incentives, because I can't order pizza for 40 different schools,' right? Like, you know, I'll never get tenure here at Harvard. And, I don't want to take you into all the sidewinders, but needless to say I was kicked out of the New York City Public Schools three times. I tried to do this experiment three times, kicked out. I mean really kicked out, Russ, like, in the middle of a school visit, told, 'Go to the car and leave.' Russ Roberts: Why? Russ Roberts: Why? Roland Fryer: We can get into that if you want to, but-- Russ Roberts: Yeah, I mean, I'm interested. Why were you thrown out? Roland Fryer: I was thrown out because of the controversy surrounding paying kids to learn. It was unlike anything--look, I was like 25, 26 years old, right? It didn't dawn on me that that provided incentives for students to do behaviors that we thought were highly correlated with achievement--and thus highly correlated with income and home ownership later--was somehow repulsive. But, people were picketing outside my house, okay? It was unbelievable. And in any event--and the political winds in New York at the time: I used to get up every morning at 5:00 am to read the newspapers, because I didn't know if the program was going to go or not go. Right? Imagine that risk, by the way, for an assistant professor in a research project that you've dumped months and months of your time. Anyway--and you don't know if it's going to go forward. So, long story short here: We were able to get 140 schools signed up in New York City. But I was a total nobody. I couldn't even convene an event where 140 principals would show up. So, I went door by door by door for 140--it's all I did for one summer, 140 schools, and signed them up. And, by the time we did that, it took years to actually get to that point--again, being thrown out and invited back, etc.--to my amazement, Dallas wanted to do something. They wanted to pay kids for reading books. D.C. [Washington, D.C.] wanted to do something. They wanted a more--it was Michelle Rhee when she was there--they wanted a more wholistic incentive scheme that rewarded homework, but also behavior. Chicago, when Arne Duncan was there before he was Secretary of Education--he wanted to do something based on grades. So, lo and behold, after tremendous failure for multiple years, trying to get from pizza to paying financial incentives, here we were. And we had--I don't know--hundreds of schools, 40,000 students or so, and we spent $15 million dollars trying to pay kids to do the things that we thought were correlated with high achievement. Now, a couple things. One: I didn't find this repulsive because frankly, everyone I know in middle-class families provide incentives for their kids to do the behaviors that they want. Okay? I'm going to really offend your listeners here. My daughters are nine and six. The other day, they didn't take their plates from the table after dinner. So, I took them and gave them a bill for $2 apiece. And now, after dinner, you should see it. They grab those plates and say, 'I'm not giving my dad $2.' So, but every middle-class family that I know, and upper middle-class family, does this in some way, shape, or form. And Number Two: I really believe that it was important for not crushing the love of learning, but fostering it, particularly in inner-city schools, where gangs and other things are giving them incentives to go in the opposite direction. Russ Roberts: And-- Russ Roberts: And, what kind of magnitude are we talking about here? Roland Fryer: Great question. It was all centered around the price of an Xbox at the time. So, in fourth grade, you could make up to $250 per year in New York. In seventh grade, you could make up to $500. Russ Roberts: So, it's real money. It's not like--it's not a quarter. Roland Fryer: It's real money. Russ Roberts: Okay. Roland Fryer: It's not a quarter. It's not what my grandmother used to give me for good behavior, which was the lack of a slap on the back of the head. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: But, it was real cash. And, look, I don't want to forget this. We opened up bank accounts for every single kid, and we deposited the money into the bank account. We did our best to try to do financial literacy, but I'm not sure it really worked, because I was walking to school one day and a kid came up to me and says, 'Yo, Professor. Would you like me to manage your money?' I said, 'Sure, but like what? Tell me about your investment thesis. How are you going to manage my money?' He said, 'I'm going to manage your money just like I do mine. I'm going to put it in the bank for a month, earn some of that interest, and then I'm going to go eat ice cream.' I said, 'No. No, thank you.' But, we did give them financial literacy. We opened up bank accounts. We did direct deposits into those bank accounts. And we have data on what the kids spent their money on. We have data on whether or not it affected intrinsic motivation. And most important for me, we have good data on whether or not it was effective at increasing test scores. |

| 8:56 | Russ Roberts: And, was the--obviously, the standard argument against this--I think a lot of people have a moral revulsion on this, just in general, and neglecting the whole issue of, quote, "other middle-class incentives." But, the intellectual claim against it would be: if you pay people to learn then they might do it while you're paying them, but you'll have taught them that learning is something that is to be compensated, and not to be done for its own sake. Now, I would just say, before I give you a chance to answer: I find that argument remarkably unexciting because they don't teach people to learn for their own sake anyway. So, it's not like we're corrupting anything. But, the real question is: the longer-term effects if any--and even the short-term effects would be valuable--but, were you able to do any follow-up over time besides the test scores, like in how many books they would read a year, and that kind of thing-- Russ Roberts: after the monetary incentives stopped? Roland Fryer: Absolutely. And, I'm going to tell you the results, but I also want to just push back on the whole supposition that somehow, if three years later we look at their test scores and they're not still positive, that somehow it failed. Okay? So, I ask my students all the time, 'Do you believe going to the gym puts you in better shape?' 'Of course.' 'Okay. Well, if you go to the gym every day religiously for a year, and then don't go again for five years, and then I check your health and say it's not that much different, are you going to say the gym doesn't work?' 'No.' In fact, it's almost proof that it does, so that you should continue to do it. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: In terms of the students, we followed them up and we looked at longer-term test scores. Let me just give you the results first, all the results, and then [?] a picture. Russ Roberts: Okay. Roland Fryer: I'm getting too excited to talk to you this morning. Number One, we designed the incentives not because we were smart, but because we got lucky. The first set of incentives we gave were for outputs. Okay? 'Hey, you do X, we provide Y.' That's the way classic economic theory, the way I was trained in the University of Chicago, would tell me to design the incentives. So, in New York, we paid kids for test scores; and in Chicago, we paid kids for grades. Those were our first two cities, and so we thought we'd do that. Then other cities came aboard and I thought to myself, 'Well, I don't want to do the same thing over and over again. Let's see if we can get some experimental variation that's halfway interesting.' So, we paid for inputs: meaning, instead of saying, 'You get a test score and then you get money': Do the behaviors we know that are important. Read books--that was Dallas. Do your homework, et cetera--that was Houston and D.C. And so, what we found, to a large degree, is that when you pay for outputs, we didn't get any results at all. Pure zeros. Okay, when we pay for inputs, those experiments, all three of them worked and were statistically significant. Okay? And, just imagine-- Russ Roberts: Okay, give us the magnitudes. When you say they worked-- Roland Fryer: Sure, sure. Russ Roberts: Statistical significance is nice. It means it's higher--different than chance. But of course you care about how big it is. Roland Fryer: Yeah, of course. I forgot I was talking to Russ Roberts here. All right. So, in Dallas for example, we paid kids $2 a book to read up to 20 books. The average payout was roughly $20. Those kids who were in the treatment group, meaning they were paid to read books, relative to a control--all these are randomized controlled trials--they advanced the equivalent of roughly two and a half months of schooling. Okay? Russ Roberts: That's huge. That's huge. Roland Fryer: If I could give you two and a half months more of traditional public school for $20 per kid, you'd take it in a heartbeat. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: Okay, similar things in Houston, similar things in D.C. in terms of the magnitude. For the real techies out there, roughly a quarter standard deviation gain, on average, for a student. So that, for us was pretty impressive given the cost, okay? Is it going to close the racial achievement gap in America? No. Is it something with a high return on investment that we should all be looking at from a public policy perspective? Absolutely, okay? Now, let's skip to more outcomes. We also looked two, three years later, and I'd say roughly 70% of the effect was still there, okay? So-- Russ Roberts: After the monetary piece had ended. Roland Fryer: After the incentives were taken away. Russ Roberts: Fabulous. Roland Fryer: Okay? Rather than going to the gym--I'll bet 70% of the effect is not still there. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: And two more important pieces. One: We measured the impact on their intrinsic motivation using the very scales that the social psychologists tell us are important. Right? And, we had no impact on intrinsic motivation whatsoever. The coefficient was positive, but it wasn't statistically significant. I was hoping it was, so I was never really worried it was negative. Because if you really get into the details of the types of things where when you remove monetary incentives you get negative results, are things that people liked to do anyway. Giving blood: you give blood, you feel like a better person. I pay you to give blood; then I stop paying you. You say, 'Hey, last week you paid me. I don't want to give any blood anymore without paying me.' Those are the kinds of things that were shown in that way. This is different, right? And, that's why I didn't understand people's objections. It's like I am somehow going into inner cities, and I'm ruining the very love of reading Beowulf, right? Have you read Beowulf? Okay, so I was trying to foster it by paying kids incentives. And, the last thing is, we looked at what kids actually spent the money on. We gave them the equivalent of a kid version of the consumer expenditure survey. The answer is, they saved a lot more than the control group, okay? So, their savings behavior was quite interesting. And, like my little friend the financial manager, they spent a lot on ice cream, video games, and shoes. And that's okay, too. But, I think those are key pieces, Because, you've got to remember, Russ, when I first started this, people said to me things like, 'Aren't you worried they're going to buy drugs?' And, I said, 'No,' you know? I didn't think but for $75, a fourth grade was going to get some cocaine. I just didn't think it was going to be possible. That's not--so you can kind of get where I'm going there. It was amazing, the resistance to this idea. Russ Roberts: Can-- Roland Fryer: But, over the years, we have paid students, we've paid parents, we've paid teachers, because I fundamentally believed it was a simple, scalable way to think about the demand side of the equation for education, right? A lot of our stuff is on the supply side, and that's fine. There's nothing wrong with these supply-side ideas. But, I don't know, I think I remember economics 101. Maybe there's an interaction term between the supply and the demand side. |

| 16:07 | Russ Roberts: The part that I find fascinating psychologically--and I don't know if you had a chance or an experience that would give you any insight into this--but, I've been an advocate for all kinds of creative things to help public schools in America when I lived there. I'm still an advocate for them. Anything: charter schools, vouchers, you name it--those are easy ones. I'd try other things. And the reason is really simple. For three generations, we failed inner-city kids with horrible schools, and it's not like, 'Well, you've got this crazy idea but we love the status quo.' The status quo is awful. Almost no one defends the status quo. Do you feel it was that those people who do care, and who have good intentions--they want to spend more money, say. They have their own solution. Okay, I understand that there's a natural addiction to your own--the thing you've championed. But, how could they not be open to an alternative in a world that's so depressing? Did you explore that with people? Did you ever have a feeling about that? Did people confess to you that you'd made them change their way of thinking at all? Roland Fryer: Yeah, that's a great question. No: No one confessed to me that I'd changed their thinking on this. But, your point needs to be double-clicked on, which is: in Washington, D.C., where we did these experiments--one of the places we did these experiments--when we were doing them, 80% of White eighth graders were proficient in math or reading on the NAEP scores, the National Association of Education Progress, and 8% for Black students. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Russ Roberts: Compared to 80. A tenth. Roland Fryer: Okay, so it's a travesty, right? We need--I agree with you, and to put it very bluntly, I was willing to throw spaghetti at the wall. Although I'm an economist, so I an idea there should be better. And then, to be serious about measurement, and those things that work we scale up, those things that don't, we don't. I just had that as a view of how to get better. We don't have this--no one had the gospel. We didn't know exactly what was going to happen, but you could try things and scale those that worked. Now, in terms of this, I think part of the reason--it was just a vitriol reaction to this, Russ. Which was, 'There's something wrong about it at its core. These kids should just love it. Don't they understand what is great about education?' And, I tease my class. I have 240 students in my undergraduate class this semester. I just teased them two days ago and said, 'I'm sure all of you are here for the love of learning. You don't care anything about economic mobility, right?' Russ Roberts: Right. Or the grades, or the credential, yeah. Roland Fryer: 'Okay, none of you don't care about any of that.' Look, what's hilarious about it, though--here's what kept me going. There were, I would say literally USA Today polled thousands of people and said 50% were for and 50% were against this idea. It's fun to get up in the morning at 5 a.m. and read that. But, I never met a kid that didn't like it, okay? Not one. Okay, I met half a kid. I almost met a kid, okay? So, I'm in D.C., and because of all the flak or whatever, I loved to give out checks for the first payment. Because I didn't want the first payment to go right into bank accounts, because those kids who didn't sign up all thought it was--this was the inner city. Kids were like, 'You're not giving anything away for free.' And so, I wanted to go, and I'd hand out checks for the first payment. Okay, so I'm in D.C. And, I'm there early. And, the principal takes me around, and I go into a seventh grade classroom and they're having a phenomenal lecture about Mesopotamia. And, the teacher introduces me, and a kid with perfectly starched--I'll never forget this kid--perfectly starched khaki pants, a blue shirt, is an African immigrant--comes up to me and says, 'Sir, I do not think we should be paid to come to school and to do well. I think I should pay you to come to school and do well.' And I said, 'I am so happy you said that. I really--' I said, 'You won't--I can't even explain how important that is to me.' They go on about the class. Thirty minutes later, I'm in the cafeteria. I'm handing out checks. Okay? I get to his name, and I read the name. He pops up, but I don't want to offend, so I fold the check and I put it in my pocket. And he comes up to me and says, 'What are you doing?' I said, 'What are you doing?' He said, 'Well, I'm up here to get my check.' I said, 'Well, no, no, no, no, no: 30 minutes ago, you impressed me by telling me you did not want to be paid for school. In fact, you thought you ought to pay me. So I'm here to be paid.' And, he looked at me in the way that only a 12-year-old can, with these sparkling eyes, this crisp blue shirt, and these crisp khaki pants, and said, 'I never said that.' So, I thought I'd met one kid who didn't want the incentives. Turns out, it was not quite true. |

| 21:10 | Russ Roberts: So, is that the bottom line for you, of that experiment? Have you told me everything you want to tell me about the results? I'm sure you have many other stories like that that would be entertaining, but in terms of the bottom line of the findings, is that your finding? Roland Fryer: That's the bottom line. I think that the key thing on incentives is they are very powerful but very tricky to get right. Okay? Let me give you an example. In Houston, we paid kids for math homework, okay? These kids in the treatment group did one standard deviation more math homework. Okay? And I even tested their price sensitivity. Russ you're going to love this. We were paying them $2 per math objective. Randomly in February, I just got an idea to estimate the price elasticity. So, Monday morning, an email went out to every school--a blast--every parent, 'This week it's $4.' Okay? Price elasticity was nearly 1. Boom: you got double the output. Okay? Waited another two months, sent another email, '$6 this week.' Boom, again, almost one. You got three times the original effort. The kids respond to incentives. And, I remember waiting for the district test scores thinking, 'This is going to be the biggest effect we've ever had.' Turns out we got a great effect on math, and almost the exact negative effect on reading. Okay? Russ Roberts: I think I got that one. I think I can figure that one out. Roland Fryer: Right? It wasn't because they lost the love of learning-- Russ Roberts: No-- Roland Fryer: It's because they substituted between tasks. Russ Roberts: Yeah, I got it, yeah. Roland Fryer: Okay? I thought what we were going to do when we gave incentives was increase the amount of time spent on school, and crowd out hanging out with your friends-- Russ Roberts: No, no-- Roland Fryer: No. These kids are very smart. They said, 'The price for crowding out friends is a lot higher than $6, but you can crowd out English.' Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: And so, I only say that to say-- Russ Roberts: No, that's fabulous-- Roland Fryer: look, very powerful, but we have to design them well. And it's really hard a priori to understand how exactly to design them well. Russ Roberts: Yeah. What gets measured gets managed, is a classic insight-- Russ Roberts: That's mostly true. And in this case overwhelmingly true. |

| 23:20 | Russ Roberts: I asked you that, for that, quote, "bottom line," because this work was done roughly--when was this work done? What years? Roland Fryer: 2008 through 2010. Russ Roberts: So, more than a decade ago. And, I remember at the time--I was almost an academic economist in those days--I was paying more attention then than I am now. But, in preparing for this interview, I went back and of course looked at your work, and looked at what has been written about it. And, unfortunately or not, most people who write about it say, 'Fryer found no effect of paying people.' Have you noticed that? Russ Roberts: Am I wrong, in that that's the assessment? Roland Fryer: No. Well, that's a whole 'nother interview, my friend. But, it's--and at best mixed results. I guess they are mixed, but it would have been nice for someone to really read the papers and say, 'Hey, here. If you're going to do it, you do it this way.' And so, I tried to enter the fray and make some--have some clarity on this. But yes, a lot of people say: no results. People don't like this. However, you know, the State of Colorado passed a law where your schools can use their Title I money to pay kids to read books, and so you see-- Russ Roberts: Accounts-- Roland Fryer: these pockets-- Russ Roberts: accounts-- Roland Fryer: that people have expanded this, but not nearly enough for my taste. I mean, the whole idea of this and other experiments was to be a lighthouse, to show the way so that other folks could adopt things that have been proven to work. And that didn't happen here. |

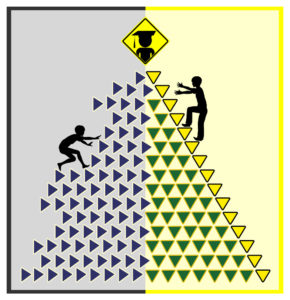

| 24:47 | Russ Roberts: So, let's talk about the five things that probably matter, that you found when you looked, I think, at successful schools that had large differences with their counterparts in things like achievement, test scores, and so on. What are those five things that you found mattered, as a separate benchmark[?], separate piece, part of your work, different part? Roland Fryer: Yes, this was work that I wanted to go deeper. That--you know, one-quarter standard deviation is great, but the gap is a standard deviation a quarter, right? So, you still need a lot more. And the question is, I was skeptical that incentives could get us all the way there. And so, I wanted--and on the other hand, there are gap-closing schools out there. I did work on the Harlem Children's Zone. There are other charter schools that were amazing. The interesting thing about charter schools is that on average, they're not that much better than public schools. But, there's lots of variance, which makes them interesting, right? So, you can try to study what makes some of them good and others not so good. They all have choices, and those choices have consequences. So, that's what we did. We took two years, and we went in and really studied, tried to understand what makes some charter schools good and other charter schools not so good. I'll spare you the details, but the five things that we found--they explained 50% of the variance in the charter school sample--were basic things like more time in school. So, I call it the basic physics of education. If you're behind, you have to tell people--you have to either work harder or tell people in front of you, 'Please slow down.' And so, that's more time in school is important. The human capital strategies: how they recruit, retain, develop teachers were important. How they use data to really inform instruction was one of the key pillars. You know-- Russ Roberts: Explain that. Roland Fryer: In 2000--yeah--in 2000, when I first got started in education, data was a real asset. Now, it can be a liability, because there's so much of it and they don't know what to do about it. And so, what we really found that was key in schools was not only did they collect data on who was passing and who wasn't in terms of objectives throughout the year, but they had plans of what to do about it, right? So, the good schools would do something like this: Every two to three weeks, they'd give a really short-form assessment: Did you understand the last two or three weeks? And, they'd have a strategy. If 80% understood it, then we'd move on. We'd take the 20%, put the in small groups after or before school, maybe even during lunch, and we'd tutor them and get them back up to speed while the rest of the class went ahead. If 30% got it and 70% didn't, we'd all slow down and we'd go back and reteach those subjects. Okay? But, if you only take one assessment at the end of the year, and like some of the D.C. schools, 92% of the kids failed, then you take the summers off--like, that's not a strategy. But, almost constantly assessing--not in a way that's high touch--low-stakes tests, where you can just understand whether or not students are getting the concepts. That was number three; very, very important. Number four was putting kids in small groups. I guess it's okay to say 'tutoring,' now, because it's back in vogue. So, when schools that were effective put kids in groups of six or less, four or more days per year. Now, this is a big important concept, because it has to be high-dosage tutoring. Tutoring for four hours a year is going to get you what you expect; not a lot, okay? It has to be high dosage. Tutoring is in vogue, but people don't want the high dosage part of it. You have to really spend the time to catch up. And, the last one is--really, to me--is the glue that binds it all together, and that is a culture of high expectations. The schools--all the schools we dealt with, Russ--had kids had issues with poverty. 88% of them came from single female head-of-households. There were crime in their neighborhoods. And that is all awful, and we ought to be working on that problem, too. But, the schools that were effective did not use that as an excuse not to educate them. They understood that they have seven hours to make up for all that. Now, some people are going to say, 'Roland, are you crazy? You can't make up for all that.' Fine, but you've got to do the best you can. And, I have a view--this is not scientific--but I have a view that kids will live up or down to our expectations. And, the schools that were effective really were empathetic and understood the challenges that kids came across the thresholds of their doors with, but nevertheless they knew that potential was distributed equally and opportunity was not, and they were going to drive those kids to be the best they could be. So, those were the five things. But we didn't want to stop there. Those were five correlations. We wanted to get causal estimates. So, we got really, really lucky over--it took us a couple of years, but we got really lucky and the Houston Public Schools asked us to come in and apply these five things in an experimental setting in their schools. They gave us the worst 20 schools in Houston. There were four high schools, five middle schools, and 11 elementary schools. They were going to be taken over by the state. That's why the superintendent wanted to do this. And so, we put these five things into those 20 schools, and let me tell you a little bit--if you have patience--a little bit exactly how we did it. Number one-- Russ Roberts: I just want to say-- Russ Roberts: It's one of the most important lessons of economics, and I would say of management, is that passing legislation does not always have the impact that you think it does, and that monitoring it is often necessary with incentives. And so, I think in this kind of--these are--I think everyone would say, 'Well, those all make sense to me.' Quote, "implementing them" is not a simple thing, because--announcing it is not sufficient. I remember a friend of mine putting a curriculum into a school, only to discover a few months later that none of the teachers were using it-- Roland Fryer: Yes, exactly-- Russ Roberts: and, asking, 'Didn't we have that workshop where we told you to use this new curriculum?' They said, 'Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. But, the new one doesn't work, so we're doing the old one.' And didn't tell anybody, right? Roland Fryer: Right, right. Russ Roberts: And, easily, that could have just been a whole year where your evaluation of that new curriculum would have found no effect, because it was never tried, actually. Russ Roberts: So, go ahead. So, how do you possibly implement that across an entire school, with how many people? Roland Fryer: No, man. Well, let me double-click on something you said, which is that these things are obvious. And, that's what's so frustrating. Because, my grandmother was a Sixth Grade English teacher. She integrated schools in 1969 in Florida. She has an amazing story of--can you imagine parking your car and being spit on on the way to class; but then, those same parents, teaching their kids subject/verb agreement, 30 minutes later? So, and when my grandmother was alive I lived to impress her. I never quite got there, but I lived to impress her. And, I remember, she called me one day; she said, 'What are you doing up there at Harvard?' I told her about the Five Things, and her response was something, like, 'They pay you for that?' She thought it was so incredibly obvious. Like, 'Of course, we should be doing this.' And, I said, 'Well, Grandma, they're not doing it.' Why aren't they doing it? Why is this revolutionary? And so, here's what we did to implement these things. Number One: We lengthened the school year two weeks, and we lengthened the school day an hour. Okay? That was roughly 20% more school--and, equivalent to what the high-achieving charters were doing. Now, even that wasn't without controversy, because I got a call from someone in the travel-and-tourism department, who was like, 'What are you doing? Kids can't go back to school two weeks early.' I said, 'Look, man. Poor kids deserve a chance.' He said, 'Poor kids? They're not going to come here to our resort.' That's fine. That's literally a conversation. So that's what we did on the time. Number two, on the human capital pieces: 19 of the 20 principals were removed and 50% of the teachers. Okay? Russ Roberts: Whoa. Roland Fryer: Yes. This was a real rehab of these public schools. Russ Roberts: Wow. Roland Fryer: Third, we brought in data systems to be able to--we did two things on the data side. One: We implemented the set of short-cycle assessments, so that every three weeks we'd get data on where our kids were. And, more importantly--and this is really low tech here--we created a series of drop boxes so that we could just drop in for each teacher exactly what they needed to know. Right? Because the test--you get a 300-page report, and you've got to figure out which one is yours. No one's going to do that. Okay? So, we did that. Four, we hired 400 tutors to come down to Houston and tutor in Grades Four, Six, and Nine. Now, we wanted to tutor all grades but this was already a $60-million-dollar experiment. We couldn't raise the money to do every grade. And, as an economist, since this was the highest-cost item--the tutoring, because the tutors made $25,000 a year--I wanted a little differentiation so I could understand whether it was worth it in terms of the return on investment. So, we brought these tutors. People said, 'Roland, no one's going to come down to Houston to tutor for $25,000 a year.' In five weeks, we had 1200 applications. Okay? People earnestly wanted to help. And, the fifth thing that we did was on the culture of high expectations. So, we took the graffiti down. We took the--I mean, some of these schools had chain-link fences, like they were prisons. I couldn't figure out if they were trying to keep the kids in or keep them out. And, we took all of those down. And we tried our best to change the culture. And I could give you examples. But, we wanted to ensure that every kid thought--had a chance, a real chance to succeed. I mean, sometimes you go in these schools, man, and they'll have a goal that 40% of the kids should have basic skills next year. How can that be your goal? Russ Roberts: Man [spoken underbreath--Econlib Ed.]-- Roland Fryer: Okay? We interviewed all the teachers; a team of people, not me, but a team of people interviewed all the teachers. And, every teacher who said something like, 'Give me some solid curriculum. I'll put in the effort. Every kid can do it. Let's go,' all stayed. All of them stayed. But, we had some teachers--I have a tendency to tell the truth here. We had some teachers that said to us, 'Look, we don't need these five things. We only need one thing.' And, I said, 'Well, what do you need?' 'Smarter kids.' Russ Roberts: It makes-- Roland Fryer: And, if you have that attitude, it's hard. You can't--you can't do the work, okay? |

| 35:45 | Russ Roberts: It makes me cry, actually. It's so--it's heartbreaking. It's, um--again, having thought a lot about education over the years, and being a parent, which is not so different than being a teacher, high expectations is fabulous. Your children may not love you every minute, and your students may not love you every minute, but they might thank you later. Roland Fryer: My grandmother used to tell me, 'You don't have to like me, but you're going to respect what I'm doing.' Russ Roberts: Yeah. Russ Roberts: I just want to [inaudible 00:36:21], your grandmother reminds me of a poem by James Dickey called "The Bee." We'll put a link up to that poem. It's about great coaches and great teachers and great teachers, so-- Roland Fryer: I love it. I love it. Russ Roberts: You're blessed to have a grandmother who was hard to please, but I'm sure that was-- Roland Fryer: Beyond that. Beyond that. Russ Roberts: I'm sure it was harder for her than it was for you. Roland Fryer: Yeah, that's what she said. Look, we did these things and we thought every kid should succeed. I'll give you one example of the culture of high expectations. We hired these amazing principals. Nicole Moore was one of the principals of one of our toughest middle schools, Key Middle School. And, there was a kid in the hallways between classes as I was touring. So, part of the thing that we did with the experiment--talking about your friend with the curriculum--is we came down every four weeks to score where they were in terms of implementation of the five tenets. Okay. So, we're down there on one of these trips, and we toured all 20 schools. It took all week. It was a whole ordeal. And, there's a kid in the hallway, and the kid doesn't have functional arms, okay? He just doesn't have arms. And, the principal comes out and starts getting on him: 'Get your butt in class. You can do--' And, I'm like, 'Okay, I'm a tough guy too, but, like, let's give the kid a break.' Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: And, when he goes off to class, she looks at me and she goes, 'Don't you dare look at him like that. He will achieve.' And she says, 'Yeah, sometimes he needs help with maybe unbuttoning his pants, or this or that. But, they found him a special pencil. He will do it. Don't you dare take it easy on him.' I was blown away by that. Russ Roberts: Yeah, that's incredible. Roland Fryer: Because it was done out of love. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: It was done out of deep empathy and love for that student, and understanding what the future held, and he did not get the basic skills in seventh grade. And, for those of us who want to take it easy on him, that's for us. That's not for them. Russ Roberts: That's true. Roland Fryer: And, that's just one of many, many examples. Okay-- Russ Roberts: So, what happened? Roland Fryer: Let's fast forward. Russ Roberts: Yeah, what happened? Roland Fryer: Let's fast forward. Russ Roberts: I'm on the edge of my seat. I know our listeners are, too. Roland Fryer: In three years in the secondary schools--middle and high schools--we closed the racial achievement gap in math, and cut it by a third in reading. In five years, we did the same thing in the elementary schools. For our high schools, every single pupil was admitted to a two- or four-year college. This is 20,000, 30,000 kids, and-- Russ Roberts: And, what was that--what would that number have been before you got there, in Houston, in the bottom high schools? Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: Maybe. All of them didn't go, okay? That's okay. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: That's their choice. Russ Roberts: Sure. Roland Fryer: The adults in the building shouldn't make that choice for them, right? Give them opportunities, and then they can make their choice. I'm an economist. I understand supply and demand. Not everybody should or wants to go to college, and that's okay. But, everyone deserves the opportunity. And so that's what we did. It's the, in my opinion, probably the most important work I have ever done. I've never worked so hard. There were real kids in there who I know, right? There's a kid who showed up in my Harvard undergraduate class and said, 'Hey, I was in Sharpstown High School. Man, thanks.' And, I broke down. Russ Roberts: Yeah, I would, too. Roland Fryer: I mean, we can do it. And, that's what gets me so frustrated, is: It's not that we don't know what to do. I'm not saying this experiment is perfect. We spent $1,863 more per kid, but the test scores are such that the return on investment is huge. But it can still be improved. The issue is not that we don't know what to do. The issue is we don't have the courage to do it. Because it's hard, and you might not win any popularity contests. So, people were really angry with me because there was a lot of teacher turnover. But the issue is: Do you fundamentally believe that these kids are capable, or not? Because the truth is, if you don't, then of course you should sprinkle little crumbs here and there, give them some backpacks, and move on your way thinking of yourself as a good person. But, if you fundamentally believe that they have the same potential as your kids, and that they are rotting away in these horrible schools, then you should not be able to sleep making a difference, and making a change. And, we can't wait. They're not going to get fourth grade back. This is it. Right now. And, so I'm super fired up about this, and that's why I did the experiment, and one of the reasons I spent nearly two decades focused on education. Because there is a way to reform traditional public schools, if the adults won't do what it takes to actually help the kids. |

| 41:34 | Russ Roberts: Did you, or have others, tried to provide a template of how to implement those five things? I'm thinking about kind of a crazy thing, kind of a slightly repugnant analogy. But, one of the reasons McDonald's is so successful--which I know you've had some day-to-day experience with in your youth--is that they didn't find a few thousand chefs or cooks who could cook as well as the first one. They found a system that would let an okay chef, an okay cook, an okay manager, do pretty well. It's not a great product, but it's a pretty good product. It's reliable. It's consistent. Have you thought about? Did you try, have you tried, have others tried, to do the kind of data systems, tutoring, etc., that worked for you in that setting? Roland Fryer: 100%. A hundred percent. It's a great question. I'm glad you asked. A hundred percent. We used to call it the 'popcorn button.' We said, 'How do we take this and make it the popcorn button?' We specifically used the McDonald's analogy. And, we did two things. One, we tried to boil this down and put together a package so that others could take it and use it. But, more importantly, we also did a revenue-neutral version where we said, 'Look. Now that we've done the experiment, we think we know what the high leverage points were. And, maybe making principals better managers, and so providing management training and feedback and guides, can make a good principal a great principal.' Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: One, that's checked out--there's nothing you can do. But, there's a lot of folks who have the passion but could use help with skill development. And so we did that. We did that experiment, too. Right? We ran that experiment: Took other--we didn't change the principals; we didn't change the teachers--we just went in and gave them the management handbook on that, and I'd say the results were roughly half of what we found when we did the big changes. Russ Roberts: Huge. Roland Fryer: But, huge, right? Because there's no--it was free. There was no cost. I mean nothing's free, but it didn't have any additional resources from the school district in terms of money. And so, look, we tried all of that. And, one of my big frustrations was that this was not expanded. We held conferences down there. People came down and saw the schools. They were blow-you-away good. Some of them were really amazing. But, we expanded to Denver, we expanded to other places, but it didn't catch fire. And the reason it didn't catch fire is because it's hard work. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Roland Fryer: It requires a level of effort and strategy that some folks just aren't willing to put in. And, some of the human capital changes, whether it's changing the people or chang in the people, are hard. And so, the superintendent of a school district in the Midwest here in the United States called me and says, 'Hey, man. I've been trying this stuff, but you didn't tell me people were going to be upset about it.' And I said, 'You can't close the racial achievement gap and win the popularity contest in the same year. You have to wait three years.' You have to wait until you have real results, and then people will come along. I think those politics are really hard to get past. |

| 45:10 | Russ Roberts: I just want to add that, you know, I'm the president of a college here in Jerusalem, and education is really hard. Obviously. My general view is that--and my wife's, a high school teacher, or was a high school teacher in America--most teachers would like to be better than they are, but they're not sure how to get there from here. You know, if you never played a sport--take an obscure sport, archery, or if you've never played golf. And, if I said, 'Here's a golf club. Good luck. Try to get the ball in the holes by hitting it as few times as possible.' You probably wouldn't do very well. And you wouldn't get better over time. You wouldn't know how to practice to get better. So, you have to give teachers--there is an innate part of being a great teacher, but most of it is learned. Being a great lecturer is a different thing. But being a great teacher can be taught, is my view. And--but, there's a second piece--which is that you have to put in the time. And the effort. And it is work. It's not like a magic trick, where you just put a switch on a different setting or a dial at a different number. You have to grade the homework sometimes, and give them feedback every night. And that means that you're going to give up something at home, maybe. It's very hard. And if you don't give people the incentive to do that, then you can only do it with attracting the kind of people who will do it out of love. And that's a scarce commodity, obviously-- Russ Roberts: So, all of this, the hard part of it--people who are skeptical about economics, they'll say things like, 'Oh, you know incentives don't really matter because you're either a good teacher or you're not.' But that's not true. Roland Fryer: I would agree. Russ Roberts: It's true there's an innate part. But the incentives, whether it's merit pay or a bonus, or whether it's the thrill of keeping your job or whatever it is, those are what create the devotion to the task. And, that is grossly underestimated in this business. Russ Roberts: I think it's just, 'Oh, yeah. I taught my class.' No, no, no. There's prep, and there's homework return, and there's time one-on-one after class with the student who is struggling emotionally with whatever it is. It all requires devotion-- Russ Roberts: And, it's much better to have it innately than to incentivize it, but you're going to have a very small school if you're only going to rely on devotion generally. You've got to have a little of both. Roland Fryer: Totally agree with you, and I'm glad you said that. Because this is not--nothing I'm saying is anti-teacher, of course. But, it's pro-teacher in the sense that we paid our teachers more, because they worked harder, right? One of the things that drives me nuts about reformers is they think that you ought to get teachers to work so hard and not pay them more. Who else in the world does that? Right? And so, yes, our teachers came for extra practice and training on some weekends, and we paid them more. The reason that we were able to make those human capital changes is because we treated people with dignity and respect even when we had to make those changes. And so, we spent money buying out contracts and things like that, so it is 100% if you--and that's why I gave that example. Any teacher in our schools that said, 'Hey, more support, more time, more training--we can do this,' all stayed, because those are the folks we wanted. And they were effective. But, we also paid really effective teachers in other neighborhoods more money to come into these schools and work. And so, we wanted--it all has to align, the incentives. It's not just about teachers. It's also about great leadership. You have to--teachers, everybody, all of us want to feel bought into a mission that's bigger than our individual selves. And so, that's why we had to have 19 out of the 20 principals be different, because they had to be able to lead. And ihis is real work, and it's hard, and it's a mission. And you can do that, but you have to reward people, you have to support people, and you have to treat them with dignity and respect. And I think our principals in these schools did that beautifully. |

| 49:13 | Russ Roberts: If you could only--if I were in a failing school--if I were the head of a failing school and I was disappointed with my results, and I came to you and I said, 'Our school is a mess. I've got mediocre teachers. They're not well-motivated. I can't get rid of the bad ones. I'm just kind of--but I care.' What's the one thing that you would suggest? Is there a one thing? Is there a thing with the biggest marginal impact, by itself, that you think might make the most difference? Roland Fryer: Yeah. It's going to have to be a one-two punch, sorry. Russ Roberts: That's okay-- Roland Fryer: I can't get--there's no golden thing--but it's important. Russ Roberts: Give me-- Roland Fryer: The one-two punch is: Understand where kids are deficient--so you need a bit of data. And then: Small groups, high dosage on those things that they need support on. Because, I have seen many, many, many times, over and over, teachers be ineffective in a group of 20 or 25; students be unruly in a group of 20 or 25. But, heck, even I can be a good teacher when there's only three kids in front of me. And so, finding creative ways to make that happen, whether it's the use of technology and grouping and things like that, you can do it. So, that the key things are: Data; Small groups for high dosages. Russ Roberts: So-- Roland Fryer: I mean, one message[inaudible 00:50:43] is: The grades where we did all five things--where we had the tutoring--are the effects of like 0.6 standard deviations a year. It's huge. Right? Like, those things are unbelievable. And so, if you can do that, you'll have a huge impact. |

| 50:58 | Russ Roberts: What would you say--well, let me ask it a different way. There's a wonderful quote from Milton Friedman. I'm going to butcher it a little bit, but basically he says, 'You know, if you want better political outcomes, a lot of people think we need better people to be politicians.' And, he said, 'Actually what you want is a system where bad people have the incentive to be good. The incentives that politicians face are the challenge, not necessarily their innate goodness or badness.' I think about this because I think about Geoffrey Canada, who I know you know, started the Harlem Children's Zone. And I had an interview with Paul Tough, ages and ages ago on EconTalk, where he featured Canada in his book. And, he learned from this experience of studying the Harlem Children's Zone that we need to take the things that Geoffrey Canada does and implement them in other places--somewhat similar to what you are suggesting. But, he wanted to do that in public schools, where my worry would be that there's not much incentive to do them well. And, he felt that way because there's not enough Geoffrey Canadas in the world. He's special. The goal can't be, 'Let's get more of him and put them in the principal position.' Is there something to be said for the argument that--again, the McDonald's metaphor--that there are people who would be good enough principals, as long as they had the incentives-- Roland Fryer: For sure. That's what we did-- Russ Roberts: to work with their teachers? Roland Fryer: That's what we did. What we did. I mean, Geoff Canada is a friend and I've known him for more than a decade. I think he's an American hero. But, there's nothing in these five things that he doesn't think is totally obvious, and what he does in Harlem Children's Zone. He does more than these five things. Russ Roberts: Yeah, of course. Roland Fryer: But, these are the core five things. And--for his schools. And so, exactly this. I was having dinner with Geoff Canada in 2008 or 2009, and I was at his house and his wife was there. I looked at her and I said, 'You know, one of my goals is to boil your husband down into pill form so I can distribute him.' And, she thought this was the most--who talks like that? Right? And, essentially, that's what we did. He was a big help in designing a lot of the questions on culture and expectations, and tutoring, and things like that. He was a big help for us to understand what those five things might be. So, this is exactly what you just described, is: taking those geniuses--like Geoff Canada and others who are running amazing schools--and figuring out what the key essential elements are so that we can distribute them widely. This doesn't take a superhuman, right? A little old nerd from Harvard can run 20 schools and have the same effects, right? And so, if the little old nerd from Harvard can do it, there's tons of principals who are way better than I am at doing this work, and they can implement it as well. Russ Roberts: But of course, your disappointment--which, you know, is incredibly sad--is that this did not catch fire. Russ Roberts: Nobody said--not enough people said, 'Oh, now that we know the things that it takes, let me learn how to implement those and transform my school.' Russ Roberts: And that is, I think, fundamentally, because it does require an immense amount of work. It does require devotion of every player down the line, from the principal--especially the principal--down. And that's just not much fun, I guess. I don't know. There's not an incentive to put it in place. People still come to your school, because in a public school as long as they live in your neighborhood, they have to come to your school, because that's the only place where they can get it without charge. Roland Fryer: They have a captive audience here. Russ Roberts: Yeah. |

| 54:42 | Russ Roberts: We talked earlier that charter schools have wide variations--some not very good, some spectacular, and the average may be a little higher than the public school system. Do you think charter schools' expanding is helpful? So, I asked you what you would do in one school. What would you do if you were the Education Czar or the Head of a School District in a bad, low-performing city? And, you weren't worried about keeping your job, because you might lose it. But, what would you do? Roland Fryer: Well, that's a great question. I don't know. I would certainly--I think there's two options I'd have to think about, and I'd want to--it probably depends a lot on the location I'm actually in. One would be to work with our state legislature to provide resources for people who want to do--implement school models that we know are effective, like this. So, when you talk about incentives, the Federal Government could have changed the incentives, right? They had the school improvement grants. They gave billions of dollars away. That's one of the ways we were able to do some of this work, was we got school improvement grants. But, even with our results, the only thing that the two political parties here could agree on--right?--the one side didn't want all the teacher turnover and that, and the other didn't want people telling schools what to do. So, the end result of the compromise was, 'Here's some money. Do whatever you think is right.' Which is exactly wrong. They should have said, 'Hey, here's the thing that we think is--the only thing that has real evidence that you can turn around a school.' But, if you could do that, and provide the guidance and the resources and the incentives to do it the right way, that would be Option One. Option Two is more radical. I think Milton Friedman would like Option Two. Or, it's not more radical. It's just different. I'll call it that. Option Two is: Let's just give the per people expenditure to the parents and let them have choices. Right? And so, that's where I would lean, because this is really hard and complicated. Because if we looked at inner cities and saw, 'Huh. There's a lot of kids there with $20,000 a year to spend on educational resources in the ways that they and their parents see fit,' then institutions would develop to serve them. And so, we always talk about competition and this kind of thing in public schools, but it doesn't really exist, right? As you said before, the public schools, as long as you're in the neighborhood you have a captive audience. But, if we changed that, and we made per-people expenditure exportable, that might be interesting. I haven't thought all the way through it, but those are the kind of two options I would be thinking about. Either we do it the right way, or we provide resources for the families to figure out how they would do that. |

| 57:31 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about parents for a minute, because I know you've also done work with parents and incentives. I think there's a lot of--well, I'll just call it racism. I think there's a lot of racism about what parents are capable of in poorer neighborhoods. A lot of people argue--whether they believe it or not, or whether they're being strategic, I don't know--but, they'll say things like, 'Well, you know a poor or single mom, how could she assess what a good school is? I mean, she doesn't know anything about education, so we can't give her the freedom to spend her money on her child's behalf. We have to top-down improve the school system through the whole district, and not allow these competitive forces. They might work in other parts of the economy, but they won't work in education because the consumer is uninformed.' We hear the same thing, by the way, without racism, about, say, healthcare. 'You're not a doctor. You couldn't----in a real free market for healthcare, which we've never had anything close to in 70 or so years in America or more, or anything remotely like it ever. People would say, 'Well, yeah, but healthcare is different because people don't know. It requires too much expertise.' I find this argument repugnant for all kinds of reasons, but I'm curious your response. And, in particular what kind of on-the-ground experiences you had with parents in thinking about their children's education. Roland Fryer: That argument angers me even more than it angers you. Any strategy that is, 'Poor people don't know anything, so let's do it for them,' I don't want to hear. Russ Roberts: Disgusting. Roland Fryer: Okay? 'They're dumb. They don't know what to do. We've got to do it for them.' I don't know, sitting right here at Harvard, there's some dummies here, too. We don't do that for them. Anyway, so I don't like that. And, I have seen on the ground what you'd expect. So, this is not going to be surprising. Everybody loves their--people love their kids. They don't always do it in the right way. I also don't parent in the right way. I'm sure if somebody re-listens, they're going to start going, 'Oh, my God. He charged his kids $2 a plate to take them into the kitchen?' Yeah. The next day I told them it was going to be $5. I'm sure that's not the right thing to do! But, I love them and I'm doing my best. And, it's the same thing with every single parent that I've ever met. And some of them have substance abuse issues and some of them don't, and there are a lot of things in those neighborhoods that are going on, in the same way that they're going on independent of income in other neighborhoods. But, the common feature is that we want better for our kids than we had. And, I'm reminded of a woman--when I was at the--I used to serve on the State Board of Education here in Massachusetts, and we were closing a bad school. And the woman really thought her kid was going to a great school, because her kid had A-pluses. And, having that conversation with her--it wasn't because she wasn't unsophisticated. It wasn't because she didn't understand what was going on. It's because they had purposefully lied to this woman. Okay? And so, if we communicate with the communities, and help them understand the set of choices and the consequences that come from those, just like we would do in any other community, then they're going to make the choices that are the best for their families. And sometimes you see, in data, that people in low-income neighborhoods make choices that rich people might not make, and so you start to say, 'Well, maybe it's not in their culture to value test scores.' No. You know what they value first? Safety. But, you don't think about that, because in the suburbs you're already safe, and so everything in the area is safe, relatively speaking, and so you choose higher test scores. But, when you look in an inner city, you see someone choose a lower test-score school, you say, 'What are they doing? They don't really know what they're doing. We can't trust these people.' Ah, we can't trust you. You haven't looked at the full data. What they're choosing is safety first, and then test scores. Right? But, you wouldn't know that until you get into those communities and actually talk to people, and understand that their preferences are just like ours. All we want is for our kids to be upwardly mobile, to be good kids, and to have a better life than our own. And so, I think that parents know that better than most. I think we just have to--it's more of an information problem than a preference problem, so it's on us to make sure that we're communicating clearly. Russ Roberts: And, is there any--when you were in the trenches in these large, massive projects, and trying to do dramatic things and interact, I'm sure, with angry parents, loving parents with you--people who were grateful to you, I'm sure. But, it seems to me that the high expectations--the fifth item on your list--would also apply to the parents? That you'd want to encourage the parents to aim high and assume that they will rise, just like their kids will. Roland Fryer: If you look in the Educational Childhood Longitudinal Survey [ECLS, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study], something like 30% of Black families think their kids are going to get a Ph.D.--when they're in kindergarten. Russ Roberts: Wow. Roland Fryer: For Blacks; way higher than for Whites. I don't know what to make of that, but I'm just saying it's not obvious to me at all that there are different preferences or views or expectations or goals. There's a different set of constraints. There's different sets of information, right? Like, I don't think--well, a lot of people in inner cities don't know what biotech is, and venture capital, and all the other interesting things that are out there. And as I said before, that's on us. So, but before we assign it to preferences, what I have found is that--when I was over in Israel this summer talking to folks, or in the suburbs of Paris, or in the 10th district in Vienna talking to the Turkish immigrants, or here in inner cities in America, we're more alike than different, man. It's really, it really is. And maybe this is just because I'm getting old and I see commonalities everywhere, right? It is. Parents want the same things. They may not communicate it in the right way, and not all of them do, of course. But, on average, what we want is pretty simple. And, the big difference is, the opportunity sets that are available to us are quite, quite different, okay? And, I think that's what we should focus on. It's about the opportunity sets, not about the preferences. |

| 1:04:13 | Russ Roberts: So, my original plan for this interview was to talk to you for about 20 minutes on education, and 20 minutes on crime, and about 20 minutes on equal opportunity ventures. We're a little over an hour into this conversation, and-- Roland Fryer: You're doing a great job. Russ Roberts: Well, I'd like to talk more about education. But, you have a hard stop in a minute, and I want to tell my listeners that if you have time down the road, we'll get to those other topics the next time you come back to EconTalk. Russ Roberts: Let's close with, maybe, a personal reflection. I am touched by the passion you still have for this area. I know it's not been your prime focus now for a while. You've turned to lots of other things, which are incredibly important. I hope to talk about those in another episode, if you return. But, I'm struck by the fact that you're so passionate--which is why I thought we'd talk 20 minutes. I thought, 'Yeah, we'll go over his old work,' but I couldn't hold you down, and I couldn't keep myself from continuing the questions. So, when you lay in bed at night and you think about this chapter of your career, this incredible--there's nothing like it, I don't think. There's no other economist--there's a lot of economists who study education. Nobody has been as innovative as you have been. There are people who have made claims and have tried to test them, but nobody's been as innovative as you have been. No one has gone to the barricades and gotten the money that was needed to test these in a serious way, rather than just a one-off aside in a school district. These are large-scale, massive efforts; and at worst, you changed the lives of thousands of kids, one of whom at least came to Harvard, and maybe a few others. But, you've had a huge impact. Not the impact you wanted, but when you lay in bed at night and you look back on this part of your career, will you ever come back to it? Is it just something that you sometimes wish had turned out maybe better? Do you feel satisfaction? Just reflect on it in your own life. Roland Fryer: It's a phenomenal question, and I'm going to answer it in a brutally honest way, as I always try to do. I am wholly unsatisfied with that work. I'm happy we did it. I think it changed some lives, not enough. I'm going to tear up, man. But, we also lost some students on the way, Russ. There's a kid named Marcus that was in a high school there. And, they came to me, and they said, 'Hey, Marcus is maybe not make it. What can you do?' I flew down to Houston--this is just one of several examples like this--talked to Marcus, and a phenomenal kid. Phenomenal kid: smart, witty, thoughtful, could get science concepts like that. But, he's in jail now for 20 years for armed robbery. And I failed him. I failed him. There's another kid in the Crown Heights, P.S. 399 [Public School #399]. He was a fifth grader, and I was told that his gangs were starting to kind of circle around him, and whether I'd take him under my wing. I said, 'Absolutely, 100%.' Gave him a flip phone at that time--I'm so old. I told him, 'Call me any time.' I was just about to get on stage to do a keynote, and he called me and he needed help. I looked out at an audience, and there was a thousand people waiting. I said, 'I'll call you right back as soon as I'm done with this.' And he never spoke to me again. I failed that kid. I lay awake at night, and I don't sleep much because I feel personally responsible for what's going on. These are my people. They're your people, too. And, we have to do absolutely everything we can, in my opinion, to change their lives. I tried hard at that stage of my life. I worked as hard as I physically could. But I don't think it was enough. Yes, we had some impact, but it wasn't enough. Will I ever come back to this? Absolutely. I never left. It's just that I thought that--and think--police use of force was actually hindering peoples' desire to invest in education; and so education has always been number one in my mind. One hundred percent. We'll talk about the venture stuff later. That's just a way to accelerate impact. The focus has never gone away. I plan to die on this hill. I will be fighting for these kids every single day, a hundred hours a week, until I take my last breath. I'm not trying to be overly dramatic. That's just true. It's just what I want to do. And, it's because I know that there's real potential. People say, 'Oh, every kid can learn.' Come on, man. Give me--of course. Duh. Right? But, like the question is: Do you really fundamentally feel that you are responsible for their economic mobility? Do you feel like we have a civic covenant that we should ensure that there's equal opportunity? That, as I said before, potential is distributed uniformly but opportunity is not? Because if you fundamentally believe that there's a civic covenant that we need to get, that opportunity should be equal--not outcomes; that's different--but opportunities, then you wouldn't rest at night, either. And so, I'm way far away from being done. I'm 45 years old. I've never had more energy. I am 100% in this, and my only wish, Russ, is that we had more young scholars who wanted to do it. Because--we have some, and I've had many students over the years--but, people think these problems are intractable. People think that if they find the wrong thing on police or education, they're going to be called a racist. People think--and we could go on. That's selfish, though. It's not about us. Right? I'll close with one story. During the second time I got kicked out in New York City, I lamented this fact to Joel Klein. And, Joel Klein said, 'What are you doing tonight?' And, I said, 'Well, nothing, because I just got kicked out of the public schools again.' And, he said, 'Let's go to a Yankee game.' So, we go to the Yankee game. We sit down. We order some bad Bud Lights or something, and I start lamenting, and I start just complaining: 'How could you guys kick me out again?' Yada, yada, 'You say you want Black role models. I've got a Ph.D. I'm working hard, but I'm trying to do my best, and you keep kicking me out,' and da, da, da, da, da. About the third inning, he raised a glass and he looked me in the eyes. And he said, 'If it ever becomes about us, let's quit, okay?' And that is probably the wisest thing anyone's ever told me. It's just so not about us, right? This is about the very fabric, in my opinion, of what the American dream is about. This is--I'm a patriot. This is about providing opportunities for everyone, so that based on their own merit, kids can rise. And I won't rest until that's true. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Roland Fryer. Roland, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Roland Fryer: Thanks, buddy. |

The good news about educational reform, says Harvard economist Roland Fryer, is that we know what it takes to turn a school around. The bad news is that it's hard work--and implementing it won't win you any popularity contests. Listen as the MacArthur Genius Award Winner and John Bates Clark medalist speaks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about how pizza parties revealed the potential of incentives to improve students' test scores, and why he's far more concerned about closing the racial achievement gap than keeping the love of learning pure. He also discusses the five best practices of successful schools, and why it's his failures far more than his successes that keep him in this fight.

The good news about educational reform, says Harvard economist Roland Fryer, is that we know what it takes to turn a school around. The bad news is that it's hard work--and implementing it won't win you any popularity contests. Listen as the MacArthur Genius Award Winner and John Bates Clark medalist speaks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about how pizza parties revealed the potential of incentives to improve students' test scores, and why he's far more concerned about closing the racial achievement gap than keeping the love of learning pure. He also discusses the five best practices of successful schools, and why it's his failures far more than his successes that keep him in this fight.

READER COMMENTS

Betty Jensen

Oct 10 2022 at 10:36am

Thank you for an inspiring interview! You identified much that works to improve student performance.

Have you done research on what is needed to improve teacher and school administration performance?

Unfortunately, I have personally witnessed declines in teacher morale and performance which were largely due to school administrations. These in turn, of course, affect student performance. A related issue involves teacher unions and the resulting lack of incentives for individual teachers. At times, the union even prevents an individual teacher from doing more to help the students.

I am afraid that until “this side of the equation” is addressed, students will continue to suffer.

Thank you again.

Eric

Oct 10 2022 at 11:59am

At about 55 minutes, Russ asked Roland Fryer what he would do if he were education czar of a troubled school district and did not need to fear losing his job.

1. If we do the second option of equitably enabling real school choice, then ultimately we will get the effect of the first as well. Once schools must compete effectively, then public schools will willingly seek to do school the right way (or else they will be replaced by new schools that will do so).

2. If we fail to empower the parents with real school choice, then we won’t get the first option either. Unless faced with a change-or-be-replaced situation, the political will does not generally exist to take the hard medicine and fire obstacle principals and teachers on the scale they did in Houston. (Teacher unions wield great influence.) Any extra “free” money for resources would continue to be spent in ways that don’t require making any of the important but hard choices.

3. Apart from any beneficial effect on motivating failing schools to change, equitable access by parents to their share of a state’s education dollars is necessary as an issue of justice. No matter what else needs to be done, we must eliminate enslavement to a neighborhood school with inferior resources based on neighborhood property values. It is both just and in the state’s long term interest to ensure that an unbiased share of per student education dollars follows each student to a school the parents have chosen.

Then (and only then) school districts will seriously care about meeting the expectations of the parents and satisfying their educational customers. At least, the schools that last and thrive will care, while others will be replaced (and none too soon).

Roland Fryer and Russ Roberts are right about the importance of establishing the proper incentives. The single most important incentive to establish is to make it necessary for schools to satisfy the parents who choose (or might not choose) to send their children to that school.

krishnan chittur

Oct 10 2022 at 12:42pm

Whenever I get discouraged by discussions about race, all the nonsense about DIE (diversity, inclusion, equity) and how a small but vocal minority gets more attention than it deserves, I remind myself of the fact that people like Roland Fryer exist – someone who has done amazing work against so many odds – yet remains steadfast in his objective – education to anyone who wants it.

I can imagine why Roland Fryer can infuriate the many in the ruling class (including many minorities who have “made it”).

I also share my fury about how people with power imagine that the poor cannot make right decisions for their kids – despicable indeed. If there was one thing that was a constant where we grew up, it was that education was critical – and my uncredentialled parents knew more about education than the many credentialled today.

I could sense the pain in Fryer’s voice about having “failed” some of his students – even as I heard that he is not done, will not be done till he can do everything possible. More power to Roland Fryer and anyone that cares about education.

Joël Sekiguchi

Oct 10 2022 at 2:00pm

This and Fryer’s gym hypothetical finally explain to me what’s wrong with Fryer’s approach: he’s not an economist, he only talks like one, because he doesn’t believe in costs. He doesn’t believe summer vacation, or childhood, has any value; he uses stuff like Xboxes as reward, but he doesn’t believe they are anything but a behaviorist lever to move stubborn little kid-units. So when he does these intense interventions, no matter how much of their lives it uses up, no matter how transient the blip in test scores is, then it’s a success. And if it’s not, then all that means is that like alcohol or violence, if schooling is not solving your problems, you just need to use more! Thus all the heads-education-wins-tails-noneducation-loses logic where he throws around dollars per unit under the assumption that it will last forever (most of these struggle to last a year) and will have all the causal effects of the original correlate (it will always be smaller, much smaller, and the more Fryer optimizes for boosting test scores, the smaller it will be, per Lucas), and if it is non-zero, then case closed.

And if you complain about fadeout?

His gym hypothetical makes the flaws of his framing particularly clear. If I went to a gym, paying through the nose in time and money, making myself miserable for months on end, and 5 years later, there is no measurable difference – the gym failed. Period. It was not a good intervention, because it did not intervene. Fryer says it succeeded and in fact, its absence of effect is a good thing and proves it works! That’s crazy talk. It is not, because we do not go to the gym for the benefits solely that day (which is good, because the immediate benefits are minimal). We go for the *long term health benefits* to our health, quality of life, and life expectancy. If you go for a short period, then it is all cost and almost no benefit. This also applies to, say, college: if you go to college for a year or two and drop out with tens of thousands of dollars in debt and no degree, Fryer apparently believes this is a success – you went to college, didn’t you? Number go up.

Jon Breslau

Oct 10 2022 at 5:15pm

So, the best way to improve scores is to…

1.) Fire half the staff.

2.) Run the remaining staff (the ones who were willing to stay and put in the work) at unsustainable levels such that there’s massive turnover (perhaps even to the point of staff leaving the profession, if the current teacher shortage is any indication).

3.) Extend the school day and school year.

4.) Spend significantly larger amounts of money.

It’s not surprising that there would be temporary improvement, nor is it surprising that this model didn’t catch on in the districts it was attempted. This is akin to when government induces sugar-high like economic activity by lowering interest rates, and then acts surprised when it didn’t lead to sustainable growth.

Most public education schools do the main thing that Mr. Roland suggests: find areas of weakness, and do high-dosage tutoring. The difference is Mr. Roland’s (and Mr. Geoffrey Canada’s, for that matter) plan allows for extended school day, extended school year, and (the higher-cost) extended contract to those workers working it. I hope he understands that while the heart is willing, the spirit (read: funds from State and County Government) is weak.

The opposition comes less from adverse educators, but more over-worked, underpaid teachers who will be expected to give more, likely at no (or less!) compensation (not merely money, but also measure to protect them against dangerous students, and legal protections).

Luke J

Oct 21 2022 at 9:44pm

#1 is addition by subtraction. Bad teachers make good teachers have to work harder. There must be some point at which it becomes a net negative, but my impression from the interview is that they did hire teachers from other schools, and it didn’t sound like teacher burnout was an observed phenomenon. Granted, I’m not familiar with Fryer’s work outside of this interview.