| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: March 9, 2022.] Russ Roberts: Today is March 9th 2022 and my guest is Richard Gunderman. He is Chancellor's Professor of Radiology, Pediatrics, Medical Education, Philosophy, Liberal Arts, Philanthropy, and Medical Humanities, and Health Studies at Indiana University. Richard, welcome to EconTalk. Richard Gunderman: It's a pleasure to be with you. |

| 1:00 | Russ Roberts: Our topic for today is greed as seen through the work of Adam Smith and Leo Tolstoy with some Hobbes thrown in. I want to start with the Tolstoy story--that you focused on in your essay--"Master and Man." And, before I begin, for listeners, if you haven't read the story yet, please do before you go any longer on this episode. Just hit pause if you can. The story is a masterpiece. You can only read it once without knowing how it's going to turn out, so consider pausing and reading the story. You can find it online, an excellent translation. We go have a link up to it with this episode, but again, you can just Google 'Master and Man Tolstoy' and you will find it. I also want to recommend the remarkable book by George Saunders, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, which is an analysis of a number of Russian short stories and it's glorious. Go read it, even if you don't like Russian stories. He got me to like Chekov--I never did. Saunders is a master teacher and if you read his book, you will feel like you're in his classroom. So, Richard, let's start with the character of Vasili. I don't know how to pronounce it. If you want to correct that, please do. What kind of person is he? What do we know about him? And, what does Tolstoy want us to think about him? Richard Gunderman: Well, I would say he's a person whose identity is bound up with his wealth. He measures his life, the significance of his life, the purpose of his life in terms of how much money he's made. He likes to compare himself to people he's known and relishes the fact that he's managed to make a good deal of money over the course of his life, to this point. And, he also thinks a lot about people he knows, who have made a great deal of money like the Muranos, who've made millionaires of themselves. Russ Roberts: And, there's a type of person like that. And, I think Tolstoy would say, we all have a little bit of that in ourselves. We enjoy material success. And, I think in the case of Vasili, he likes keeping score. It's not just that he's got a nice comfortable life--which he does. He's got a couple of coats and his poor servant, who he is going to spend this evening, that the story relates, has one, and it's got holes in it. So, there's this contrast constantly in the story between the master, Vasili, and his servant Nikita. Nikita has very little. In fact, he's often in debt, either because of his drinking problems in the past. He's put those, it seems, behind him, when the story starts. But as an employee of Vasili, he's often getting--he's getting paid in kind. He's got a very tough material life. His wife is living with someone else and his child--and his life has a lot of troubles. And, on the surface, Vasili seems to be remarkably comfortable. What do you think Tolstoy wants us to think of this man, Vasili? Richard Gunderman: Well, I think Vasili doesn't really love his wife very much. In fact, she's referred to as his 'unloved wife.' And, when he looks on his son, he sees his heir. He thinks of his son as his heir, implying he's the person to whom his wealth will pass. And, I think Vasili sees himself as an exceptional person, better than essentially everybody he knows, and operates with a sense of invincibility. That, he's on the path to greatness: that greatness is going to be measured by his wealth; and those around him just don't get it. You know, he looks on others with disdain because they don't realize that you have to devote your every waking moment to building your wealth. |

| 5:03 | Russ Roberts: Yeah, I think he literally says--Tolstoy literally says--that Vasili thinks of his son as his heir. Now, of course, he is his heir, presumably. But, the fact that he expresses it in that language is a way of saying that he sees him as an object--the conduit through his wealth will flow. What's wrong with that? I mean so, okay, so Vasili is a little bit materialistic. He's really into sharp dealing. He enjoys very much getting a deal, taking advantage of someone in negotiation--literally taking advantage of them or ideally out-negotiating them. But, he's very eager to cut quarters[corners?] if he can. We have a pretty vivid picture of the man, I'd say. So, what's wrong with that? I mean, what's the big deal? So, he's into money. Is there a problem with that? Richard Gunderman: Well, for one thing is, as you said, Russ, he wants to get the best possible deal, which means that he will emerge with the most profit and the person he's dealing with will be taken advantage of to the fullest extent possible. For example, as the story opens, it's the day after St. Nicholas' Day, and he's headed to buy a grove, a stand of trees. And, he's already plotted in his mind how he will take advantage of the landowner, including outright deception and fraud. He's going to pay the surveyor what to him is a token sum of money and get the surveyor to decrease the number of trees and the amount of acreage, so that he can make the purpose at an even greater profit. And, so, this is somebody who--I'm going to use a term I don't understand very well--but who I think kind of sees life as something like a zero-sum game. There's this fixed amount of resources that's going to be redistributed and he wants to emerge with as many resources, as wealthy as he possibly can. And doesn't really concern himself about the welfare of the people with whom he's dealing. Russ Roberts: In fact, his relationship with Nikita is really quite extraordinary. There's a handful, 10 maybe, maybe two handfuls of conversation between the two. The whole story takes place on their journey to this grove of trees on a windy and snowy night. And, I didn't count them on my Kindle, but the word 'snow' is mentioned an extraordinary number of times, as is the word 'wind' or 'windy'. And, if you do read the story, I recommend that you read it in a warm place, ideally with a big fire blazing, because you're going to get cold reading the story. Part of the artistry of the story is that in many ways, it's repetitive. It's deliberately repetitive. And often that wears out the reader. In this case, to me, it just deepens and enforces--reinforces--the lessons and maybe we'll come back to that. But, okay, so he's a sharp dealer. He likes negotiating and taking advantage of other people. I was going to say, he brags to himself that he's going to sell the horse at a price that's way beyond what it's actually worth. But, he's kind of leaning Nikita and Nikita is his employee and Nikita didn't have a lot of options in life, so it's kind of a tough deal to turn down. Nikita knows he's being taken advantage of. We get his inner thoughts that, 'Yeah, here's another time the boss is going to take advantage of me.' And, the part that's [bittersweet?]--sort of tragicomic about it is that Vasili acts like he's a good guy. Like, he thinks pretty well of himself. It's not just that he's really great at business and negotiating, but yeah, he treats people pretty fairly, more or less, is the way it sort of describes it. And, says so to poor Nikita, who kind of shrugs, takes it, and moves on. It's not the best relationship. Richard Gunderman: Yeah. It's the art of the deal. And, I think you're right. Vasili is a master of self-deception. He sees himself in his own eyes as a very good master, as a very good steward of his resources, and really takes comfort in the knowledge that he's better than everyone else. But, as we see over the course of the story, he's really not a steward. He's an exploiter. Russ Roberts: Yeah. It reminds me a little bit of The Death of Ivan Ilych, which another story of Tolstoy's I recommend. And, the charm--it's powerful--'charm' is not quite the right word--the effectiveness of the story, I would say, comes from the disconnect between how the main character sees himself and how we, as the reader, are able to see him. The brilliance of Tolstoy is he doesn't say, 'Look at this hypocrite.' He doesn't say, 'Look at this self-deceiving person.' He just slowly gives you his inner thoughts, describes what he does, and we, as the reader, see the man more fully than the man sees himself. It's quite amazing. |

| 10:21 | Russ Roberts: Before moving on to Hobbes and Adam Smith, I want to say one thing about the story. I mentioned the repetitive nature. So, the wind is always blowing. The snow is always piling up. They can't see anywhere. They get lost numerous times. In fact, they start off at one point--early in the story, they start off and they end up in a town. They leave--they go through the town; and some number of hours later they're back because it's so snowy and blizzardy that they they've gotten lost. And, they stop there for a while and sort of regain their wellbeing. They have some tea and alcohol and they sit in front of a warm fire. And they're asked to stay, but they go back out again. And, why do you think Tolstoy has that second--two trips through this town? Why couldn't he just, okay, they stop in the town. There's some interesting things that happen in the town, really interesting things. It's relevant to the story. We learn a lot more again about the character's attitudes, both of them, Vasili and Nikita. But, why do you think Tolstoy has them get lost there twice? And, each time, by the way, each time he passes through town, at least three of the times, he sees it's a terrible image of frozen clothing on the line, drying. Of course, it's not drying: it's frozen and it's waving wildly, desperately in the wind. And, George Saunders, in A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, says it's a signal. 'Hey, it's bad times here, folks. Don't keep going. Stop.' And, they just ignore it. In fact, the shirt is a white shirt, like surrender, and it's sort of a hint like 'Surrender,' and they refuse. They just keep going. Because, there's money to be made. And Vasili, he's afraid some other competitor will get the grove that he's interested in taking from this guy at a good price. Why do you think Tolstoy does that? Richard Gunderman: That's a great point. Vasili's wife, Nikita, the peasant family he visits in the village--all of them warn him not to go. 'Can't you just wait a day? Maybe two days?' But, Vasili is eager to make the deal. He can't think about anything else. He's worried that some other purchaser will show up in the meantime. Kind of a ridiculous notion. They'd have to be as crazy as he is to travel in this weather, but he's afraid the deal will be taken out from under him, so he insists on going. And, as you say, he sees those clothes on the line, he sees wormwood, which is kind of a traditional memento mori, a sign of our mortality, but he doesn't see what those signs mean. He can basically just see the dollar signs-- Russ Roberts: Yeah, exactly-- Richard Gunderman: that completely fill up his field of view. And, it blinds him--not just to the safety of others, to his responsibilities as a husband and father--but it blinds him to his own safety. And, that's an excessive, I think, desire to make money. Russ Roberts: Yeah. The point I wanted to make about the repetition or the recurrence of images and the passing through the town more than once. A set of unpleasant things happen to them more than once. They go off the road more than once, the horse gets lost more than once, the horse gets worn out more than once. They're being pulled on a sledge by a horse. And, by the way, Tolstoy is really into horses. He has a lot to say about interacting with horses, taking care of them. And, in many ways, the horses are the heroes of the story. They're always put upon and you sympathize with them. But, those recurrences for me are Tolstoy is saying something about the nature of life. That for some of us and at some stretches in our life, we just make the same mistakes over and over again, because we're not paying attention. Either we're blinded by the draw, the pull of the deal or the money that you mention, or we just don't notice that we're making these mistakes over and over again. The irony of the story is that Nikita is the dirt-poor peasant. He has a lot more sense than Vasili out in the wild, in the natural world. In the natural world, you really want to be with him and not with Vasili. You want to be with Nikita. And, yet in his own world, the world of Vasili, he's a master. He's spectacularly skilled. And, I think what Tolstoy is trying to tell us is that there's a lot of things in life besides--obviously besides money. But even the more general idea that there are other things in life that are going on and you need to have an awareness of a richer and fuller picture of what's important, is driven home by those repetitive scenes. It's almost comic, if it weren't tragic. It's the--they get plenty of chances to redeem themselves, and they just--they miss most of them. So, I found that very powerful. Richard Gunderman: Yeah. Vasili is a big fish in a small pond and as long as he can keep his life perspective, frame his life in that small pond, he's a fabulous success whose prospects are as bright as they can be. But, once you take him outside of the village, remove him from his property, even though he has 3000 rubles in his pocket--and by the way, 2300 of which are borrowed from the church. He happens to have these 2300 rubles in his possession. But, once he gets out--you know, you think of King Lear on the heath, Act III of Shakespeare's King Lear, the naked human being out in the elements. You know, under not only the starry night sky, but in the midst of a blizzard, all of a sudden it's not clear which way is north. All of a sudden it's not clear what your buildings and manufacturing facilities and investment portfolio really amount to in that kind of context. And, I think it's that being taken out of that context, that plays an essential role in helping Vasili to see what's really real, so to speak. He comes to realize that he's been living in something of a fantasy world or with too narrow a range of view. And, being out there in those circumstances confronting death itself changes his view of life. Russ Roberts: Yeah, I guess it's not that subtle to point out that Vasili is lost in many ways, not just physically and that night, but more generally. I forgot about the 2300 rubles: it's an amazing thing. It's in the first paragraph or so, maybe second paragraph. It says, 'Oh, he had 2300 rubble from the church.' That he's, like, the steward--he's, like, the treasurer of the church--and he has 700 of his own. And, Tolstoy doesn't even give it an aside. He just states the facts. He took 2300 rubles of the church money, added 700 of his own, so he had 3000 rubles. And, the price he's intending to pay is above that. It's clearly the down payment. But, he never explains what he's thinking, I guess, because he doesn't have to. We just realize, 'Oh, he is a dishonest person, and he feels entitled to take the money that isn't his and use it for this purpose,' even though, and maybe, he intends to pay it back. We don't know. It's left totally unstated. It's crazy. Richard Gunderman: I think Tolstoy really places demands on us as readers. I spent much of my life thinking the moral life was a matter of right and wrong. There's some things you're supposed to do. Other things you're clearly not supposed to do. As long as you follow those rules, you're okay. But, Tolstoy isn't going to tell us what's right or wrong. The story doesn't open with Vasili Andreevich Brekhunov was a greedy bad man-- Russ Roberts: A rogue-- Richard Gunderman: He just tells us what's on the Vasili's mind. And this is classic Tolstoy. He presents little clues, hints, asides, subordinate clauses that actually reveal everything. But, the question is: Can we see them? I mean, for Tolstoy, I think the moral life is much less than that or of following of rules, and much more a matter of noticing. Paying attention to, recognizing what needs to be seen or heard or felt. And of course, Vasili misses opportunity after opportunity to do so. And, I hate to use the word 'symbolize,' but in a way, as you say, is symbolized by the fact he's constantly traveling in circles while he's in that blizzard. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I just want to mention one other Tolstoy short story, which I love, called "How Much Land Does a Man Need?" This ["Master and Man"--Econlib Ed.] is a long story. It's a very long story. It's called--I think you'd call it a novella. It's something like 50, 60 pages, meaning, dozens of pages. I don't remember exactly how long it is. But, "How Much Land Does a Man Need?" is a similar story. It's about five pages, but it's also beautifully told. He has an ability to build up tension and concern, just with--effortless. It appears to be effortless. I'm sure it's a craft he worked very, very hard at. |

| 20:25 | Russ Roberts: Well, let's turn to Hobbes and Smith. What would Thomas Hobbes think about the character Vasili, the person, the man? Would he judge him? Tolstoy clearly wants us to see him as a failed human being--a man who is lost, who is traveling in circles, who is not paying attention. And we're going to come back to paying attention in a little bit. But, what would Hobbes think of him? Richard Gunderman: Well, if you read Leviathan, I think Hobbes thinks we're fundamentally egoists. First, as a matter of description, we all put ourselves first. And second, even normatively, I think now, Hobbes thinks that we are to put ourselves first when we make decisions. So, the fact Vasili is constantly thinking of himself and trying to make a profit--in fact, as big a profit as he can in all his deals--is in a way the natural state of human beings. And, one we'll probably never be able to transcend. Russ Roberts: Well, you could argue--you don't--but you could argue that Adam Smith feels the same way. Adam Smith certainly is a strong believer in self-interest. Certainly believes we have a tendency to put ourselves first. His famous example, we've talked about many times on the program, of the person who hears about the loss of millions of lives in China due to a natural catastrophe might say something, 'Oh, that's terrible.' Might think about it for a minute. Might worry about where his factory is, if it's near China and the earthquake. But he's going to sleep like a baby. On the other hand, if you tell him he's going to have to have an operation tomorrow--he's going to lose his little finger--he won't be able to sleep. And, so, Smith clearly understood that, and I think he's right about both those two things. I think, he understood human beings very well. Isn't that Hobbes' view? I mean, is Smith any different? Richard Gunderman: Well, I think Hobbes thinks that we are like billiard balls on a pool table. Basically, atoms that occasionally knock into each other, but our natural status is that of isolated entities. And, our primary view of each other, I think, is one of fear, for Hobbes. We have to be afraid of each other. Somebody may come and take our stuff or even take our life. And, that's why we need to form governments--Leviathan--to protect human beings from taking undue advantage of each other: creating Hobbes' so-called state of nature, where life is solitary, poor, nasty British, and short. My reading of Smith--and by the way, you're much more of a Smith scholar than I--but is that Smith thinks we're born into a world where cooperation, collaboration, sympathy are natural to us. We are born into networks or tapestries of human relationships. And, that's why cooperation and collaboration come so naturally to us. I think Hobbes would be building his fortress, but Smith might be building some kind of cooperative or collaborative endeavor that redounds to the advantage of both parties. Russ Roberts: So, I just want to make the exclamation point of this. I think both Hobbes and Smith think that human beings are mostly self-interested. But, what you're adding is that that is in conflict, often, with getting along in a world that's filled with other people. And, we don't just bang into people as billiard balls. We care about them. We love them. We are sometimes afraid of them. We work with them in many collaborative ways to build things in commercial enterprises and nonprofits that try to help other people. The essence of life is that we are a social animal--human beings--and economists have kind of ignored that, more or less. Economists are always looking at, 'What's in it for me?' That is the economist's view. What's in it for me could include the satisfaction from helping someone else. But, what I think is in Smith--and I think any thoughtful person who is not an economist--is that we also care about doing the right thing sometimes even when it doesn't redound to our well-being directly. You can try to shove that back into the model and say, 'Oh, well, doing the right thing is what gives you pleasure.' And, I disagree with that. And, I argue instead that a lot of times we do things that aren't fun, don't give us pleasure. We wish we could keep the wallet we find in the street and buy something with the money. But, we think it's the wrong thing to do, so we give it back; and we're not really happy about it because I wanted the money. But, some of us give the money back. Give the wallet, find the owner and give the wallet back. And, Tolstoy, I think, how would Tolstoy fit into that? Richard Gunderman: Well, I think Tolstoy is very aware of the fact that every human being is part of a larger whole--with a 'w'. That, every one of us is born into the world totally helpless, entirely dependent on the care of others. And, while over time we acquire more independence or self-sufficiency, we are in fact throughout our lives dependent on others. I think for Tolstoy, particularly the family--it's hard to lead a complete full, rich, human life unless you're part of a family and unless that family is to some degree thriving. I mean, who would think of cheating their child, stealing from their mother? I mean, wow--from a narrow, I don't know, economic point of view, that might seem like a good idea. You know, 'I left mom's house with an extra thousand dollars.' But anyway, anybody who could even think in those terms is, as you said, Russ, lost. I mean, they're on the fast track to perdition. We should think of our mothers, and our children, our spouses, and so forth as ourselves, or that we and they are part of something larger than each of us. And, it's only by protecting and promoting what's good for that larger whole that we can really thrive, ourselves, and in a way even be ourselves. If you take me apart from my family, put me in a strange city or in solitary confinement in a prison, I assume, over time, I might dissolve as a person, at least the person I am. Now, hopefully, I'd be able to make friends in a strange city. But, in solitary confinement, it might become impossible to be human. Russ Roberts: Well, you might have. If you have an iPhone and good Wi-Fi, you might be okay. But, that really is the right question when you think about it. We've put ourselves into a little bit of solitary confinement over the last decade or so with our focus on our phones. |

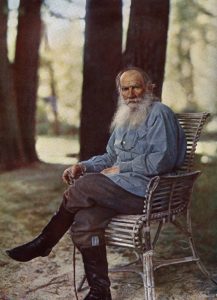

| 27:55 | Russ Roberts: But, I want to try to challenge your view, and my view as well. A footnote on the side is that Tolstoy was a religious man. There is a Divine element of this story. In a way, it's very, very small. It's only introduced on maybe a couple of pages. In another way, it's the whole story. So, it's an interesting fictional element of the story is the role that the Divine plays and how it speaks to people and keeps them focused on things other than themselves. But, I want to put, I want to put that to the side. I want to challenge my view. I want to come back to what I asked you before. So, he only cares about himself, he only cares about making a deal, why is that--? Hobbes says, according to you in your essay, which we'll also link to for listeners. Hobbes said, 'It's rational to look after yourself.' He didn't think about evolution, but you could argue it's evolutionarily fit. Ayn Rand certainly stressed that; you mentioned that in passing in your essay. What's wrong with that? I mean, so what? So, he sees himself as not connected to other people. So, he puts himself first. That's what everybody should do, the argument might go. And then, through the invisible hand--that's a misunderstanding of Smith, but I'm trying to be fair to the other side--we'll say it's Mandeville in The Fable of the Bees. Some people are trying to make money. They'll build businesses, and they'll in fact, yeah, I'll just say it that way. So, why is that--what's wrong with that? Richard Gunderman: Well, in part, I think, it's the diminishment of the selfish or egoistic or greedy person. They are so curved in on themselves that they can't really see and feel for other human beings. So, if they were in relationship with other human beings, bound together with them, doing their best to help at least some other people lead better lives, I think they would both find a great deal more fulfillment in their lives and also become a better version of themselves. I mean, one thing we could say is: Leo Tolstoy was rich. That's a true fact. Okay, let's move on to Dostoevsky. You know? No. Learning that Leo Tolstoy was rich has told you next to nothing about Leo Tolstoy. It's missed everything we really need to know about Leo Tolstoy. And, while that's especially true for Tolstoy, it may be very true of every single human being. Simply knowing somebody's net worth has told us next to nothing about who they are, what larger wholes they're a part of, what difference they're making every day, and what legacy they're going to leave. Russ Roberts: But, the economist might argue--and certainly, I know many who do argue this way--'You know, you're just a paternalist, Richard.' Here's this man, Vasili. He's happy as a clam. He's got a lot of money. True, his wife is unloved. True, he sees his son as an object--the person who is going to be his, the caretaker of his assets when he dies. But, he's happy. Thinks a lot of himself. You're suggesting you know better about what's good for him. And, certainly, Tolstoy is doing that. He's happy to do it. But, wasn't Hobbes onto something? Wasn't--what's the big deal? So, you think he's missing out. He doesn't. He's got those choices. He's chosen to ignore them and to get pleasure from what floats his boat. And, what floats his boat is daydreaming about how much money he's got. In the modern world, he'd be looking over his stock holdings in the Wall Street Journal every day, and he'd be counting his money. You know--big deal. Richard Gunderman: Well, I certainly am not suggesting we slap handcuffs on Vasili and torture him until he adopts a different point of view. But, I think sensitive readers can feel very sorry for him. He thinks that his greatness and invulnerability lies in his deal-making and his wealth. But in fact, it's caused him to neglect other facets of his life that are equally or even more important. I don't despise Vasili, but I feel very sorry for him; and I harbor a deep hope that he will find a way out of that rat's nest of greed in which he is enmeshed. And, I think a lot of readers can feel the same way. Tolstoy is really, in the person of Vasili, inviting us to hold up a mirror to our own lives. Vasili's sole concern, Tolstoy tells us, is how much money he's made and how much money he might still make. That is his sole concern. What is your sole concern? What is my sole concern? What are the sole concerns of our families and neighbors and fellow citizens? If it's just how much money we've made and how much money we might still make, no matter how rich we are, we are leading deeply impoverished human lives. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I have to say--obviously, I don't disagree with that. I mainly agree with it. I do think it's interesting if we think about evidence for that view. And, I want to--we'll come to Smith next. And if I forget, you'll remind me, I hope, because Smith has a lot to say about this as well. It is interesting--I've never thought about it--but it is interesting that most great works of art on this topic are about a character who realizes that there's more to life than money. Usually, it doesn't go the other way. Usually, I can't think of a work of art--I can't think of a great movie, a great novel, a great short story--where a character has been really good to the people around him or her, and then one day, he wakes up and realizes he should just forget about him and focus on making money. Now--and you could add to that, the wisdom of religions and other sage advice that emphasize that there's more to life than money. One of my favorite versions of this is no one on their deathbed wished they'd spent more time at the office. And, the motto of life isn't the person who has the most toys wins. So, it's pretty clear that culturally, there are forces trying to push us--Ebenezer Scrooge should be another example--there were forces trying to push us away from Vasili. That: he is to be judged. His mistakes are to be avoided. And, yet, I have to admit a little piece of me has some--well, it's not true. I'm trying to be even-handed. I can't be. I think Tolstoy wants us to feel sorry for him, to see him as a pathetic person, especially the gap between his own self-image and our view of the man. Richard Gunderman: Yeah. I agree completely. There's something very sad, constricted, narrow, superficial about the life he's leading; and he clearly has the potential to be a better husband, to be a better father, to take into account to a greater degree the interests of people who work for him and the people with whom he's striking deals. But, he's got this weird, distorted conception of human life in which it's all about him and how much he has; and that takes a great toll on the other people in his life. He's actually damaging other people through his inability to see other people--to feel what's important to them and to see how he might enrich their lives rather than basically grasping and hoarding as much as he possibly can. |

| 36:26 | Russ Roberts: So, earlier I made fun of the economists' view--a little bit and I try to be fair to it more or less--but the standard mainstream economist view is--it's captured in the phrase, 'consumer sovereignty.' People choose--whatever they do is what they prefer. And so, in a way we have no right to judge Vasili. And to do so is to be paternalistic, to impose our preference function on his. And, yet, I think the key to thinking about this in an economist's way is to recognize the possibility of self-deception. Certainly Smith understood that. Let's turn to him now. Smith--listeners know my favorite Smith quote, "Man naturally desires, not only to be loved, but to be lovely." And, Smith, by 'loved' and 'lovely' didn't mean just romantic love and physical appearance and lovely. Smith meant praised--by 'loved': praised, admired, being significant, being respected. And 'lovely' meant being worthy of praise, worthy of respect, worthy of admiration. [Time mark 37:36] And, he has this incredible passage where he says: If you want to be loved, you want people to pay attention to you. One way to do that is to be rich, powerful, and famous. And, the other way is to be wise and virtuous. [See Part I, Section III, paragraph 29 (Chap. III), of The Theory of Moral Sentiments by Adam Smith: "We desire both to be respectable and to be respected.... The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers, and, what may seem more extraordinary, most frequently the disinterested admirers and worshippers, of wealth and greatness."--Econlib Ed.] And he says: There's two paths presented to us. And he calls that first path--the rich, powerful, famous path--the "glittering" path. And, he says: If you follow that glittering path, the "great mob" of humanity will be interested in you. Which is very fun. Right? It's fun when people think you're important, pay attention to your every word, want to know how you dress, and want to copy you. He says: That other path, the wise and virtuous path, it's not so shiny. And, he calls it, I think, a "small party" of people who will appreciate you. So, what he's saying there is actually--I think it's true. But, it's quite profound because what he's saying is that there's a seductive nature to that first path of riches, power, and fame. And, it's easy to get seduced. It's easy to be blinded by that brightness. And, I think that is the essence of the cultural view on these issues: is that, it's not that, 'Oh, you feel differently about this than I do.' It's that, 'You don't see the full picture. You don't realize there's this other path. You don't realize that you're being seduced. And, you end up on your deathbed wishing you spent less time at the office, and you'll regret it.' So, 'Hey! Hey! Stop! Stop going in circles. Stay in the town, get warm.' Anyway, sorry, I'm rambling there. Carry on. Richard Gunderman: Well, one way to look at it is: we're born with certain desires. And, you could say infants are selfish, in a way. They get hungry. They cry. They're not reaching out to other people to help them satisfy their needs and desires. So, maybe, we are born somewhat selfish or egotistical, and egoistical: maybe that makes sense. But, the question is: Are we meant to go through our entire lives as human beings, family members, neighbors, and citizens operating with the lower desires we were born with? Or, do we have the potential to educate our desires, to seek and find fulfillment in higher things, say human relationships, even things like literature, art, music? Maybe we aren't born with that, but maybe we can develop it. And, for somebody who does develop it fully--and I think, toward the end of the story, Vasili has a chance to develop that more fully--that turns out to be the much more fulfilling path in life. And, more importantly, maybe doing the will of the Divine. Maybe that's what we're meant for. Maybe that's what we're told we've been meant for; and it's a terrible thing when the development of those desires from lower to higher is interrupted and somebody ends up going through life with a relatively primitive or base sense of desire and nothing more. Russ Roberts: And well, Tolstoy certainly thought of the Divine--again, as I mentioned before, the divine aspect of this. But I don't think--you don't have to be a religious person to appreciate it. |

| 40:59 | Russ Roberts: I think the--I'll come back to this quote, I use it in my new book--Wild Problems is my new book. And, in there I quote this line from John Stuart Mill: "Better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied." And, I didn't write about this part of it, but one of the parts, aspects of that is that: there's a lot of us that, of our humanity, that's a lot like a pig. We like wallowing in mud. We call it something different. Right? We like when they put out the food for us, like the farmer does; and we like rubbing our back on a tree when it's itching. And, there's a lot of human experience that's like in animals. And, I have a deep attraction, Richard, which I confess to, to the parts of my existence that are less like in animals. And, I don't know whether that's hardwired into me--the desire for, say, the transcendent or the creatively human, the art that you were talking about. I do feel virtuous--beside the divine aspect, the religious aspect--when I exercise faculties that I suspect animals can't. And, I don't know how important that is. I don't know. Richard Gunderman: Yeah. A great example of that would be: any of us could think about one of the best meals we've ever enjoyed. Possibility Number One: the best meal I ever had was defined by the food that was on the plate and how much of it I ingested. That could be. Maybe eating is just about ingesting nutrients and surviving to another day. But, I think you and I would say when we think about the best meal we've ever had, it wasn't defined by the food on the plate. It was defined by the other people we were sharing the meal with. Table fellowship, conversation. I learned something. I made a new friend, or I deepened a friendship, or the relationship with my wife or my children or my parents, or what have you. That, I would say is a higher conception of the role of sharing meals in our lives than just that we're ingesting nutrients. So, sure. We need to feed our kids at the breast or the bottle when they're first born. But over time, we want them to learn at the family dinner table that there's a lot more to living than just staying alive. And in fact, some of life's deepest pleasures and fulfillments lie in the kind of conversation that tends to happen at the dinner table. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I'm a big fan of the book by Leon Kass, The Hungry Soul, which deals with a lot of these issues that I also reference. I think it's in Virginia Woolf's novel, To The Lighthouse--is that the name of the book? Is it To The Lighthouse? I think it's To The Lighthouse-- Richard Gunderman: Yeah-- Russ Roberts: There's a dinner party, if I remember correctly in there that--I still enjoy that meal. I got no nutrients from reading about it, but there's a feeling of the kind of comraderie and love and affection. And, the special thing that people produce together when they interact together conversationally and through emotion and through facial expressions where food is the medium, but it's not the main event. And, it's a great way to think of it. Richard Gunderman: I would say commensalism, which basically means eating together. Sharing a table is not only on the decline, but rapidly declining in our own age. We, Americans, at least take far fewer meals together than we used to. A very high percentage of meals in the United States are consumed in isolation. And this has become trite, but you often see people gathered at a table, but every one of them staring down at their cell phone. Nobody is in conversation with each other. So, if a person really wanted to do something about this, I think one thing to do would be to foster commensalism. How can we awaken ourselves, our family, our friends, our colleagues to the joys that come from eating together? We need to make time and space to actually sit down at a table, share a meal, and engage in a conversation. We can write principles on a blackboard, mouth platitudes, but we actually need to make a practice in our lives to develop that habit. And, I think anybody who works to develop that habit is probably doing a great deal of good in their family and in their community just by being an exemplar and an advocate for the importance of commensalism. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I've never heard that word before. Commensalism? Richard Gunderman: Yeah. 'Co-' means together, of course and 'mensa' literally means table, but the idea is we're sharing a table. Russ Roberts: Yeah, that's lovely. I confess, though, that in the last 10 years, I've become very enamored of eating lunch by myself and scrolling through Twitter, catching up with websites that I like. Maybe reading--reading a book in theory on a bookstand or on my Kindle. And, it's interesting, again, of how seductive that is. And, to invest in that alternative--which doesn't always pay off: sometimes you meet, you have a lunch with somebody, and it's boring. Or, they talk the whole time and it's just not so fun. But, the art of a good table conversation--or any kind of conversation actually, as opposed to being alone--is definitely on the decline. It's-- Richard Gunderman: Yeah. I'm glad, Russ, to hear you use the word 'art.' It might really be an art. If you want to become a good painter, you've got to work at it for a long time. You want to become a good musician, it takes real effort over a sustained period. Maybe it takes real effort to cultivate the art of table fellowship and table conversation. And, if we don't invest in cultivating it, it's going to lie fallow. You know? It's going to deteriorate over time; and I'm afraid that's what a lot of us are doing. Russ Roberts: And, it's a different art to host versus to be a guest. It's a different experience. You have a different set of obligations in those two settings. A lot of times we neglect that, I think, and focus too much on what we want and what we think we need. And, it's a really lovely point. I want to read a quote-- Richard Gunderman: I'm sure, Russ, Vasili is seated by himself, looking at 'What's the Dow [Dow Jones Industrial Average] doing today? What's the Ukrainian situation doing to my personal net worth?' That guy is not involved in table conversation. He's plotting the next deal, how he's going to take advantage of the next naive person who crosses his path. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I think of him--and I see myself like this sometimes and, when I'm eating alone--is: he's got his nose in the feedbag or his snout in the trough. So, he kind of focused on the physical pleasure of chewing and eating and consuming. Which is part of our makeup. So, it's up to us if we want to try to transcend that. It's hard to do. I've talked about being on silent meditation retreat, where you're supposed to eat thoughtfully and chew thoughtfully. Notice what the food is, notice what it smells like, notice its texture on your tongue and in your mouth. And, when you do that, when I've done that a few times on retreat, it's an extraordinarily sensuous and intellectually-, emotionally-exhilarating experience. And, when you come back from a retreat, you think, 'I'm going to eat that way at lunch every day.' And, I don't. It's hard to do. The other stuff is the website and the other distractions are distracting, but to eat without distraction--and without conversation in this case--it's not what you're talking about. It's a different aspect of--of the physical. It's really an amazing experience. I recommend it. You can read about it anywhere on the web, I'm sure: eating mindfully. It's unbelievably fabulous. But it's really hard to do. Richard Gunderman: Right. My waistline might belie this, but I'm going to make this declaration anyway: I would rather skip a meal and have a great conversation than feed my face. So, I need to be a more mindful eater, no doubt about it. But, I ultimately would like to be the kind of person who would sacrifice a meal for the sake of a good conversation. And I say again, when I think of the best dining experiences I've ever had, I'm not sure I even remember what was on the menu in some cases, but I sure remember the conversation that took place at that dinner table. Russ Roberts: Well, you're clearly not a member of my family, Richard. My family members--my direct family, my children, my wife--they could tell you the menu from years ago. They'll say, 'You know what that dinner we had with so and so? I think we had--' So, I think you may be a little unusual, or maybe my kids are. |

| 50:57 | Russ Roberts: But anyway, I want to read a quote from your essay which I really like, and we'll talk about it. You say, First, our intellectual and cultural interests incline us to see some things clearly and to ignore or at least pay less attention to others. In this sense, the very act of attending to something can be a kind of moral act. What do we attend to most regularly and closely--the performance of the financial markets and new opportunities to advance our career and wealth, or the unfolding life stories of our family and friends and the opportunities such relationships provide to contribute to the welfare of others? Likewise, these same intellectual and cultural interests incline us to see things in certain ways, tending to interpret them in some ways and not in others. For example, upon learning that someone has given a large gift in treasure, talent, or time to someone in need, a psychological egoist such as Hobbes would ask what he or she hoped to gain from it, while Smith might instead regard it as a noble instance of the virtue of generosity. Now, I'm not sure Smith and Hobbes are that different there, but that's not so important. I really want to--it's interesting--but I want to focus on the first part: This idea of attending. The idea of paying attention. We mentioned it in passing earlier. Expand on that. Richard Gunderman: Yeah. I think--you know, the world is presented to us, I think, as an invitation. What do we notice? What catches our attention? What do we dwell on? And, if we become captured by little things, trivial things, superficial things, that's going to impede our ability to pay attention to the things that matter more deeply. And, in that sense, attention may to be at the very heart of the moral life. You know, my wife, or one of my children, or a friend is trying to tell me something that means a lot to them, but I'm glancing at my cell phone. You know? Or thinking about a talk I need to give later in the day, or something like that. I am not fully present. I am not fully attending to what they're saying. And, by the way, they know it. My family is very good at calling me out on that. And I suspect other people's families are as well. So, that's actually a blessing, to have somebody call you out on it. 'Are you really listening to me? Are you here or are you thinking about something else?' But, if we can really attend to what most merits our attention, I think it opens the possibility of really becoming better people and leading better lives. On the other hand, if we neglect the things that matter most, the moral principles we follow aren't going to amount too much in the end. So, this business of attending really matters. I'm in a profession--medicine--you know, we talked about the head of the medical team as the attending--the attending physician on the Gastroenterology service, or something like that. I don't think that's an accident, that that person is called the attending. Maybe they are the people who by virtue of their training and greater experience are supposed to see more clearly than anybody else what really needs to be attended to here. And, I think that's true not only in medicine, but in life. |

| 54:28 | Russ Roberts: I think it's a really deep point. I'm going to try to say it a slightly different way, I think. I think it's slightly different. Really, there's two things going on here. And, the first is just to pay any kind of attention. To be alert. And then the second one would be, what do you pay attention to? They're both important. It's very easy to go through life paying attention to very little other than yourself, or very little than other than your financial wellbeing, or very little other than what gives you physical pleasure, your looks. Things that we would normally again, perhaps unfairly classify as superficial. But, it's the second part of--so it's hard to pay attention to lots of things. And, you might think about what those things should be. And, I don't think--we don't educate our children very well in this concept. It's certainly not part of school. This whole idea--I mean, we talked in passing about mindfulness and you could say even just thoughtfulness--this idea that you would notice, say, the distress of another person. It's one thing to say, 'I noticed that she was crying. That he was bleeding.' These are easy ones, relatively. But, there's subtle things often that people share that show pain and damage and heartache. And, they're hard to notice unless you're paying attention. And, I think a lot of what you are saying in that paragraph--that I think is quite profound--is that just the art--the act--and it's an art also--of paying attention, is a skill to be worked on. And, then you could start thinking about what you want to pay attention to. There's the episode we did with Lorne Buchman on his book, Make to Know. He talks a lot about the artist who doesn't plan out in performance art what's going to happen, but they attend to what might happen. They're paying attention. They're waiting. They're waiting to see something. They're waiting to experience something. They're waiting to notice something. And, this sounds like--you know, it's one thing to sense another person's distress. And [?], it's all kinds of things. It's about what you focus on, how you devote you spend your life. And, I think in terms of morality, we often think about action--reasonably so--but attending, paying attention is another aspect of the moral life that you're suggesting here that I think is really beautiful. Richard Gunderman: Yeah. I think the greatest jazz album ever cut, Miles Davis's "Kind of Blue." I mean, the musicians, people like Cannonball Adderley and Bill Evans showed up at a CBS Studio in New York called The Church, not knowing what they were going to play. And, that album may be the greatest album in the history of American Jazz, is improvised. People had to listen to each other and respond to each other in real time. And, Tolstoy's short story, "Master and Man", is a great example. At one point, Vasili in the blizzard decides he's got to save himself. He leaves Nikita in a hole in the snow and rides off on the horse. Now, as you've already indicated, he ends up right back at the sledge with Nikita. But, once he gets back, he sees something stir in the sledge. It's Nikita. Nikita said something like, 'I'm dying.' Vasili hears that. He attends to it. He responds to it. He decides to open up his opulent, luxurious, warm coats, spread them out. And, to lie down on top of Nikita, sharing in a way the very most intimate resource he has, namely his own body warmth. I don't think he said, 'Hmm, what would Immanuel Kant or John Stuart Mill tell me to do here?' He just in the moment heard and responded. And, in that response, he discovered an identity of self that he never knew he had. Russ Roberts: And, there's one other piece of that I think is interesting--I've never thought of--which is a couple other scenes before that, he's cold. Both of them are cold a lot of the time, mostly Nikita. But, Vasili is cold, and he's struggling to fall asleep because they've decided to--they're stuck there for the night is what happens. And, he has this terrible sense of panic. He's afraid of dying. And he soothes himself by going through his investments and thinking about how much money he's going to make. It's a form of distraction. And he forgets he's cold. He forgets he might die. And he's okay. But, the second time, he can't do it. He can't soothe himself. The panic rises up within him. And, I think that panic is an interesting metaphor for the challenge of paying attention. So, many times our minds are racing with our worries and our fears and our excitement, sometimes. It's not all bleak. But it makes it harder to pay attention. And so, up until that scene you just described, Vasili is incapable of paying attention. All he can do is be distracted either by his panic--his mind racing in fear--or the way he soothes himself with this pacifier of his daydreams about his financial success. And, that makes it hard for him to notice that the person next to him is also cold and is also afraid of dying. And, you know, I always like this line: 'Be kind every once in a battle.' And, I think it's so true. It's hard to be a human being and it's easy to forget there are other people like you struggling to be human beings. And, the paying-attention part is what redeems a lot of the lesser side of ourselves. Richard Gunderman: Vasili learns what's really worth paying attention to. Two quick sentences from Tolstoy's short story. This is referring to Vasili: his money, his shop, his house, the buying and selling, and Mironov's millions, and it was hard for him to understand why that man, called Vasili Brekhunov, had troubled himself with all those things with which he had been troubled.

'Well, it was because he did not know what the real thing was,' he thought. I mean, what we're really talking about, isn't so much good and bad. It's a matter of real and unreal. Vasili has tried to build his fortress, his mansion, of something fairly insubstantial that ultimately offers no comfort as he confronts the possibility of his own mortality. But, he learns in that encounter with mortality, that there's something more substantial to which he can devote his life; and he chooses to act on that, even though the circumstances are dire. |

| 1:02:00 | Russ Roberts: So, you're a doctor. Right? And medicine in some dimension is a mechanical art. It's about the anatomy of the body, chemical interactions of pharmaceuticals with our innards. We talk about bedside manner. It probably has--it certainly can comfort a patient. It may contribute to their health. We understand that there's the placebo effect and psychological aspects of healing and curing that are quite complicated. But, I'm curious to what extent you're reading of things like Tolstoy affects your practice of medicine. In other words, you talked about the attending physician. Does Tolstoy, and other great works of art, does it help you attend better? Does it make you a better doctor, do you think? Richard Gunderman: Well, I'd like to think so. I think it can help make all of my colleagues better doctors. But it only does so when we become better human beings. I mean, when will we learn that in order to be good doctors and good economists, we must first become good human beings? But, one of the things you learn is that, I feel very privileged that we have the best diagnostic and therapeutic tools that physicians have ever enjoyed in human history. It's an immense privilege to get to practice medicine in this country, in this age. But, the human mortality rate remains stubbornly fixed at exactly 100%. None of us gets out of this alive. And, if we can treat our patients and colleagues as fellow pilgrims on this path that ends in mortality, I think it enhances our capacity to treat one another with compassion. You know? Rather than disdain, the way Vasili treats Nikita. So, just being more aware of our shared humanity--the fact we're cut from the same cloth, we're made of the same alloy--that may not sound like much. But, I believe that can be a transformative insight that can become a habit and really change what we attend to in every patient encounter. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Richard Gunderman. The story is "Master and Man." I'm not going to spoil it, but the title is one of my favorite parts of the book--of the short story. Richard, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Richard Gunderman: Pleasure. Thanks, Russ. |

Physician and careful reader Richard Gunderman of Indiana University talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about how Adam Smith and Leo Tolstoy looked at greed. Drawing on Tolstoy's short story, "Master and Man," and adding some Thomas Hobbes along the way, Gunderman argues that a life well-lived requires us to rise above our lower desires. Join Gunderman and Roberts for a sleigh ride into a snowy blizzard, where you won't find your way by following rules, but rather by recognizing what needs to be seen.

Physician and careful reader Richard Gunderman of Indiana University talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about how Adam Smith and Leo Tolstoy looked at greed. Drawing on Tolstoy's short story, "Master and Man," and adding some Thomas Hobbes along the way, Gunderman argues that a life well-lived requires us to rise above our lower desires. Join Gunderman and Roberts for a sleigh ride into a snowy blizzard, where you won't find your way by following rules, but rather by recognizing what needs to be seen.

READER COMMENTS

Ethan

Apr 4 2022 at 9:31am

Russ is right that Tolstoy is a horse aficionado. But I think it is deeper that than. He uses the horse to illustrate the contrast between Vasili and Nikita.

Nikita treats the horse as a friend of some sort. They have a banter; they have a communication; they have a mutual respect. At various points Nikita let’s the horse drive the sledge back to the road. Before hunkering down himself, Nikita wraps the horse in a blanket for the night. When the horse brings Vasili back to the Sledge after attempting to save himself, I read that as the horse acknowledging they are better off trying to survive with Nikita. Nikita loves the horse. He works the horse, but he treats it with respect.

Nkita is to the Horse as Vasili is to Nikita. A Russian serf was similar to a farm animal in the hierarchy of Pre-Revolutionary Russia. Vasili does not care for Nikita’s comfort; he does not concern himself with the holes in his clothing; he does not bother to consult with Nikita on the prudent actions. He only looks to Nikita when he is desperate, and even then grudgingly so. He is the Master that does not care for the man. Nikita is the master that cares for his charges.

At one point they pass another carriage that is full of celebrants that are drunk. They are driving their old donkey in an unseemly manner in the eyes of Nikita. He has respect for the animal that the drunks do not. There is something there about the power of drink and Nikita’s recent conversion to sobriety, something that hints at the meanness in all of us. But Nikita has turned away from his vice. Vasili maintains his, and he metaphorically beats Nikita with his sharp dealing. He does not respect an aging and over the hill servant.

Another theme of note is the glorification of the Russian peasant. Not so much in the life of being a peasant, but the attending to those around you, no matter their station in life, the mutual respect for your fellow man, the simple life that is focused on family. This is really Russ’s point about Smith and the mistake of focusing on the “glittering path.” Nikita is a good man, despite his mistakes. He displays the kind of attitude and joy that we should aspire towards. His treatment of the cooks wife when preparing to leave is an example of the way he was recognizes and relishes the people around him. It reminds me of War and Peace and the character of Platon Karataev. Or even in In the First Circle, Spiridon Danilych. There is a focus on the wisdom found in the simplicity of those that want only for a peaceful and familial life. A stark contrast to Vasili, Napoleon, or Stalin. There is even more to be said about the family dinner the two travelers attend and the family is ostensibly breaking apart. But I will leave off with my amateur analysis there.

Thanks for the reading inspiration and the thoughtful conversation about the human experience.

Russ Roberts

Apr 6 2022 at 8:42am

Great insights, Ethan. Wonderful analysis. I would also encourage the Tolstoy story “Pacesetter” (sometimes translated as “Strider ”), a story told from the perspective of the horse which as in “Master and Man,” allows Tolstoy to express some very perceptive observations about humans.

Ethan

Apr 6 2022 at 11:48am

Thanks Russ. I have been reading a lot of Russians lately, Chekov and Turgenev especially. Love Turgenev, but struggle a bit with Chekov grabbing me. Will definitely read the Saunders for help there. Excited to read Tolstoy recommendations as well.

I am working my through the Levi and Ellison readings now. I appreciate this content. Drives me to be a more critical reader and think about the ongoing conversation these authors are having. The first Betts podcast blew me away. Really looking forward to hearing from him again.

Dan

Apr 4 2022 at 6:35pm

This being a podcast, people who haven’t read “Master and Man” may prefer an audio version. There’s a public domain recording of the Project Gutenberg version on Librivox, a service of the Internet Archive which finds volunteers to read Project Gutenberg books aloud.

Most podcast apps will understand this URL, allowing you to subscribe if you copy and paste it in:

https://librivox.org/rss/826

AtlasShrugged69

Apr 5 2022 at 11:46am

My issue with Master and Man, (and the same issue I have with most shows on Netflix), is it’s reliance on an extremely one-dimensional (to the point of absurdity) dynamic character. No one in the real world behaves as Vassily in Master and Man. As soon as I imagine a character this successful, then add to it his insane decisions in the middle of a Russian Blizzard, I have this nagging cognitive dissonance… Someone intelligent enough to raise his status in life as Vassily has done, should at least have the ability to weigh the risks of travelling in such conditions vs earning a decent return on some Timber. Anyone foolish enough to attempt it would not have risen to Vassily’s status, and anyone who had the patience, foresight, and wherewithal to succeed as Vassily would almost certainly have weighed the risks as MUCH GREATER than the potential reward…

All that aside, to use such an obviously flawed story to try and prove that “Greed is bad”, and “Self Sacrifice is Holy”, is juvenile at best, and completely unhinged from the lives of capable, ambitious people who have grown up in poverty or lower class. We don’t all have the luxury of being College Professors who can argue over whether “commensulism” (conversing while eating…) is an art, and if it’s more difficult as a host or a guest…. When you have to WORK to provide for yourself and your family these considerations quickly take a back seat to A: putting food on the table and B: eating as quickly and efficiently as possible to continue achieving A. Same goes for attentiveness. Also, how can your best meal have been for the conversation?? My favorite meal makes it impossible to even FOCUS on conversation! You should both come over some time, when you taste the perfect medium-rare ribeye, one of my mom’s twice baked potatoes, some smoky, peaty Ardbeg… you’ll be more lost in the wonderful flavors than Vassily and Nikita in that snowstorm…

In Atlas Shrugged, one of my favorite characters is Hank Rearden. He developed a new type of steel, working long hours, studying, at times neglecting his family, building a successful business and creating jobs for hundreds of individuals. Yet his family see him as a horrible person for this success, and no matter how much of his time and energy he devotes to his wife/mother/brother, they continue to bemoan his lack of empathy for the poor, his social ineptitude, and his ‘disgusting’ self-interest in making money by selling his product. He SUPPORTS them all through his ‘selfishness’, yet it is never enough for them. Curious to hear you contrast this scenario to Vassily’s… If he spent more time with his family would he somehow be a better character? What if this meant less work on his farmstead so that 2 less laborers were needed, is it worth their livelihood that Vassily spends more time with his family? What if you actually have a shitty family, people who manipulate you and don’t really care about your well-being?

Vassily’s supposed catharsis, feeling some meaning in his life for the first time by warming and protecting Nikita from the cold, is ham handed and poorly contrived. Allow me to once again suspend my disbelief as Vassily does a complete 180 from his life’s entire moral philosophy, with no hint of lessons learned to support this change. It’s a nice idea, but falls flat when the character has no REASON to suddenly feel this way. I guess you could argue his impending mortal end was the catalyst, but it’s just asinine to think Nikita AND Vassily are such bumbling oafs as to continue forging through a blizzard; no one behaves like that. And if you want to show some fundamental truth about human nature, at least have your characters be human, and not just caricatures.

I’ll be honest, I don’t care whether Hobbes or Smith is more closely related to my ideas about ‘greed’, but anyone who tries, fails, tries again, fails again, and continues trying until they succeed, deserves all the wealth and success that comes their way, regardless of how revenant they are of those returns, and regardless of how they view their family and/or employees. Without individuals like them, most businesses wouldn’t exist. No one starts a successful business working under 30 hours per week, browsing twitter and perusing websites on their paid-for ‘lunch break’.

Luke J

Apr 7 2022 at 6:29pm

I thought of this section of the story when I read your comments about Vasili and Hank Reardon.

The likeness ends there.

Vasili is not Tolstoy’s Reardon. Vasili is a scoundrel – a cheat – who provides no stated benefits to the community. Maybe Tolstoy wrote him as as one-dimensional because Master and Man is a parable on the fruit of avarice.

Atlas Shrugged is not a parable nor does it extol the

vicevirtue of greed. The novel’s greedy characters (Lillian Rearden, Dr. Ferris, Wesley Mouch) are villainous, whereas our protagonists, Hank and Dagny, are productive, useful and admirable. Sure, Hank Reardon and Dagny Taggart are self-interested, and they may not care about the unfortunate humanity; but their desire to profit through legitimate enterprise sets them apart from the corrupt, rent-seeking, blackmailing characters.Whatever Rand’s personal views of greed were (and I think she was deeply mistaken about the meaning of the word), I doubt she’d agree with your sentiment that cheating and stealing is okay because #poverty. And I think many poor persons would object to your characterization that they’re too busy consuming calories to have a party once in a while.

AtlasShrugged69

Apr 8 2022 at 12:57am

Please disregard my poor person statement, that was my own insecurity and the liquor talking…

Vassily provides no stated benefits to the community? Your own quote betrays you: “A shop, two taverns, a flour-mill, a grain-store, two farms leased out”, if those are not benefits to the community then you must be living in a utopia. Where does the text say Vassily has stolen to gain any of that? My definition of Stolen means using force or the threat of force to take property which belongs to another. If he doesn’t do that, then he can tell his neighbor pretty much anything he wants to get him to sell his Timber; they are both individuals, capable of entering a contract, for whatever price Vassily is willing to pay and which his neighbor is willing to sell; Caveat Emptor. I find the examples of his ‘cheating/stealing’ unconvincing: Using church funds to finance the Timber sale – Perhaps he has an agreement with the church? (Being such a successful businessman, maybe they allow his use of their cache for a nominal rate) Furthermore, if Vassily is really ‘stealing’ and ‘cheating’ his neighbors/customers to fuel his greed, wouldn’t word get out? Why would people continue using his products/services if he is really as horrible as you’d have me believe? Yet another flaw in this story… One I’m sure Smith or Hayek would notice immediately.

On Atlas Shrugged, how many flour-mills, grain-stores, or shops do Mouch, Lillian, or Ferris (hereby MLF) operate? Rand is right that they are to be looked down on, but not for the reasons you state: The heroes of Rand’s novels compete and succeed in free market enterprises, besting the competition and worse, government legislation designed to stop them. MLF do not provide a beneficial product or service, they use crony capitalism and government intervention (and in Ferris’ case Higher Education ‘Expert-ism’/Bureaucracy) to succeed, which, if they were honest and said their goal was to advance their own status/progeny, they would still be ok in my book (Though a far cry from Hank or Dagny..), However – they claim their interest is in the ‘greater good’, which sets off my Bologna-meter. Regardless, I can’t criticize them any more than I can a poor person who takes advantage of welfare or food stamps, they are looking out for number one, and it is the system which allows this ‘gaming’ to happen which deserves all criticism. Similarly, I place no blame on Vassily bribing the surveyor if this is a common practice in Russia in the 1700s; the criticism should be with a governmental system which allows or encourages this behavior. And if this surveyor is an independent contractor, I still don’t blame Vassily – But it IS remarkable that such a surveyor stays in business if his reputation is so easily bought…

Luke J

Apr 9 2022 at 6:22pm

We do not need to make excuses for Vasili’s behavior. Tolstoy establishes within the story that Vasili is a bit of a crook. In the fifth sentence, we learn that the owner of the grove is offering 10K rubles “simply because Vasili was offering 7.” The youthful landowner does not know the value of his own property, but knows Vasili (at least by reputation) and if Vasili is offering 7, then it must be worth a lot more. Is Vasili simply a good negotiator? No, because Tolstoy tell us Vasili has already colluded to artificially price fix, and that Vasili might bribe the surveyor to devalue the land, and that a portion of the deposit is coming from the church.

Speaking of the church money, Tolstoy wants us to know these are alms given in accordance with the Feast of St. Nicholas (in my opinion). Vasili is a church elder and thus has access to the money. What should be used for the poor, Vasili takes for personal gain. It is a large stretch to imagine Vasili’s use of church funds as “per agreement” rather than theft. And it is theft, even without the use of force. St. Nicholas pops-up again at the end of our story as Vasili solicits the saint for a miracle in exchange for his life. Tolstoy injects another of Vasili’s misdeeds: the candles Vasili sold to the church for the feast. These seem to become the source or focus of anxiety in Vasili’s dreams/visions as he is dying. Tolstoy uses the candles (which symbolize the Light of Christ) and St. Nicholas (a symbol both for temperance and favor to oppressed over their oppressors) to reveal the fault of Vasili’s character.

Why, if Vasili is so bad, do the people continue to use his products or services? Here are a few possible explanations:

What is seen vs. what is unseen. The community knows he’s swindling them, but look at the shop, the taverns! They settle for the goods Vasili provides because they lack the calculation or imagination to understand the trade-offs.

Lack of alternatives. 1870s rural Russia is awash with snow, not options. Nikita himself is nearly a slave and does not receive compensation as a laborer in the way we expect in the 21st century. He knows he is underpaid (and often unpaid), but he admits he has no other option and does what he must.

They are Russian. Speaking of doing what one must, there is this kind-of-fatalistic attitude of the story’s characters. I think the word “must” appears well over 40 or 50 times. Here’s an example:

I see this in Crime and Punishment and In the First Circle, though those are my only other exposures to Russian literature. So, if Vasili is a cheat, then he is a cheat. He is who he is. And who is to change any of that?

I admit that I could be wrong about all of them. I’m not sure it really matters. To me, Master and Man is a parable. The oppressor eats the fruit of his own labor and the result is death. I agree with you, slightly, that the end is a bit ham-handed. But it is still interesting to consider the implications of a Master being placed in position of a simple man (i.e. a peasant) when his agency is taken-away. That is really Vasili’s “redemption;” not a religious or Christ calling, but a recognition of the plight of one’s less fortunate fellow man.

AtlasShrugged69

Apr 9 2022 at 11:20pm

Agreed on just about every front, I admit I had only inattentively listened to the story before the EconTalk episode, and upon a closer reading you are absolutely correct; Vasili is at least guilty of stealing the alms and probably more. No doubt 1870s Russia is a different world compared to what you or I can imagine today. Russ is fond of saying “the only thing stopping people from getting out of poverty is a briefcase” (I probably butchered it but basically moving away from poor communities with no opportunities to more urban areas with many opportunities); Must be all but impossible in 1800s Russia.

One of my biggest flaws while reading fiction is getting overly concerned with practical applications of stories, and simply taking as gospel logically inconsistent facts as the author presents them (as is probably obvious from my comments above..) After listening to this story, I spent some time trying to think about a way this story could be modernized. The only thought I had was if a medical manufacturing business owner died, and his son inherited the company, and the father’s last words were something like “Make sure it stays profitable…” And the son started swindling their suppliers, cutting employee benefits, cutting corners on manufacturing the product; basically increasing margins but at the cost of sales and quality, and then ironically the son has some horrible disease and the hospital he is admitted at uses his company’s products which he cut corners on, and it fails and he dies… (I’m not Tolstoy…) Anyway Tolstoy’s point is well taken, and I think your takeaway is accurate; pursuit of profit above all inevitably leads to self destruction, though I think all humans engage in self destructive behavior in one form or another, so making as much money as you can before you implode might not be the worst way to go. The real question we should all be asking is: Would you rather be Nikita or Vasili?

Luke J

Apr 11 2022 at 10:33pm

Ah. This is a good question and I’ve been thinking about it since reading your comment. There is some goodness in the simple Nikita and so I can honestly say I would rather aspire to be Nikita. But, I think I’d rather be Vasili and have his money. My answer might be different if I’d never tasted wealth – if I had always and only known poverty. But I guess I’d rather be Vasili and hope that I could have a chance at redemption than be Nikita and never hope to be comfortable.

Anyway, it sounds like you’ve a good premise for a new novel. Good luck!

Shalom Freedman

Apr 5 2022 at 10:14pm

Conversations wander and arrive sometimes at points of surprisingly great interest. This happens in this conversation a number of times. At one such point Dr. Richard Gunderman speaks about the highlight of a kind of communal dining in which conversation becomes more central than the food, and in which the real enrichment is of the heart and mind. He regrets the decline in such conversations and attributes a certain part of it to the Internet and Smart-Phone world where people prefer to dine alone with their own machines. Russ Roberts agrees and yet qualifies by saying how much he can enjoy the time with himself and his own projects when taking a meal. I would add another somewhat discouraging point. How many boring meals have we gone through sitting next at a table to people we cannot spark up any real conversation of interest with? How many times have we been bored alone with our own machine and longed for human company and conversation? Is it all as simple as ‘Different strokes for different folks at different times and places? And even for the same person at different times and places? And here another point, that doesn’t it much depend on the character and quality of what we are taking interest in?

Bob Rogers

Apr 7 2022 at 7:13am

I think there is a modestly large genre of art that is the opposite of lying on your deathbed wishing you had spent less time at the office. Call it “The Young Wastrel.” A young life wasted on various forms of irresponsibility and selfishness – substance abuse chief among them. Sometimes the wastrel turns his life around like Scrooge. Sometimes he dies unaware like Vasili. In any case, he would be better off spending more time at the office.

John Pinkerton

Apr 7 2022 at 11:26am

Would it matter whether Jeff Bezos counts his money with his spare thoughts or contemplates all the thriving consumers whose lives he has improved? Those are two sides of the same coin. In the story, we have a largely hypothetical world where that coin has only one side.

I for one am grateful that Russ spent hours ignoring his family to write about Adam Smith. I’m ok if he takes a moment to count the extra money he’ll leave to his kids. I doubt in his final years he’ll regret those extra hours at the office.

The humor and brilliance of Tolstoy is revealed in the subtle details that cleverly foreclose any benefit we might assign to Vasily’s counterparties. But let’s not let the story stop us from attending to consumer surplus, innovation, and social thriving that hitch their wagon to wealth and status seeking.

Luke J

Apr 7 2022 at 4:23pm

It would matter, and they are not sides of the same coin. There are many ways to enrich consumers without profit to oneself and there are many ways to harm others while benefiting monetarily.

Vasili Andreevich Brekhunov is in the latter case. His scheming provides no consumer surplus. Indeed, he enriches himself through cheating the peasants of his community. E.g.: trimming candles in the church and reselling them; using church funds to procure private land; overcharging Nikita for a horse and pretending it’s a kindness. This isn’t gains through trade. It’s theft.

I too am glad that Russ “ignored” his family to write How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life,” but the adage about deathbed wishes isn’t that one never spent time in the office. I think most people understand this sentiment to mean that those additional hours probably cost more than benefited in the long run.

Jerry Benuck

Apr 7 2022 at 5:30pm

There is another aspect of Vasili’s philosophy revealed in section VI, after he decides they can no longer proceed on their journey. That is that gain is achieved through pain. “Because I stick to business. I take trouble…” And then, “Blizzard or no blizzard I start out. So business gets done. They think money-making is a joke. No, take pains and rack your brains!” So while he is driven by material gain, he also believes that he overcomes them because he is willing to sacrifice / take pains. He further explains that God rewards him for his sacrifice, “Take pains and God gives.”

It would seem that in the end, Vasili’s transformation is a change of priorities from material gain to a higher purpose – but his philosophy / his methods are still the same — Gain (saving Nikita) is achieved through pain (sacrificing his life).

Vasili was always willing to sacrifice (endure pain) to achieve his objectives. Tolstoy story reveals the transformation of his purpose.

Ensign Underwood

Apr 7 2022 at 6:05pm

Professor Roberts,