| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: November 14, 2023.] Russ Roberts: I want to let listeners know that this conversation with Niall Ferguson has two main topics: freedom of speech on American college campuses, and the role of Henry Kissinger in the 1973 Yom Kippur War between Israel and its Arab neighbors. We discuss how this moment in Israel and Middle East history as Israel fights Hamas compares to that time in 1973. This conversation was recorded a few weeks before the death of Henry Kissinger, which is why there is no reference to Kissinger's passing. And I would also add a few days after my conversation with Niall, I was interviewed on free speech on the podcast Tzarich Iyun, and we've linked to that as well, which is something of a follow-up for me to the Ferguson conversation and my thoughts. Today is November 14th, 2023, and my guest is historian and author Niall Ferguson, the Milbank Family Senior Fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, and a trustee at the University of Austin. Niall, welcome to EconTalk. Niall Ferguson: Good to be with you, Russ. |

| 1:38 | Russ Roberts: Our topic for today is the role of politics and speech on college campuses and maybe elsewhere. And if we have time, we're going to pivot to your book, the second volume of your magisterial biography of Henry Kissinger that you've been working on, and in particular his role in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. And, I'm sure we'll talk about other things as well. Let's start with speech. What's the state of speech, discourse, and politics at American universities, and what has the aftermath of October 7th taught us about what's going on there? Niall Ferguson: Well, it's not great. In fact, it's very bad. The state of academic freedom and more broadly free speech on U.S. campuses is dreadful. And, you know this from surveys by, for example, Heterodox Academy, which my good friend Jonathan Haidt created. And, they do an annual survey of a really large sample of U.S. students and they ask them a whole bunch of questions. For example: Do you feel you can speak your mind in class? And, more than 60% across the country say no, they self-censor. And, when they're asked why they self-censor, they say because they're afraid of being denounced or condemned by their classmates. They worry less about what the professors are going to think. And, it can't therefore be anything other than a shocking state of affairs. When I was an undergraduate at Oxford back in the early 1980s, we had a rather heady sense that we could say whatever we liked and we could run thought experiments out loud, and that was part of the way that we learned. I'm sure we were very obnoxious. In fact, I know we were. But, I do think that we enjoyed academic freedom, as did our professors--we called them dons--because they quite enjoyed saying outrageous things too, and I think that helped us learn. If you had told me then that 40 years later the places in the United States where there was least free speech, where people felt most inhibited about saying what was on their mind was going to be university campuses, I would have just assumed you'd taken some very powerful illegal substance. So, this is a very strange turn of events. And it's been going on for a while. It's not news. I can remember encountering cancel culture back nine years ago when Brandeis University first invited and then disinvited my wife, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, to be one of their commencement speakers. And, that was part of a pattern of disinvitation and cancellation that got steadily worse. And you can track the number of those incidents going up year after year over the past decade or so. What's interesting, Russ, though, is that the aftermath of October the 7th of the hideous atrocities perpetrated by Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad against Israelis revealed to many people who had not really been paying attention what we'd been complaining about for years. And, the way that worked was in two stages. First, people were shocked to discover that on Harvard or Stanford campus or the Penn campus, there were protests in support of Hamas. In support of the Palestinian cause. There were a few protests of course, but mostly by Jewish students against what had happened and in support of Israel. But the protests in support of the Palestinian cause were much, much larger, and featured clearly-supportive pro-Hamas statements and placards, odious chants like, 'From the river to the sea,' implying the eradication of the state of Israel. That was Step One. That shocked many people, particularly alumni of those universities. But, Step Two was that the university authorities--the Presidents and Provosts--then published lame word salads trying their best to say as little as possible. And, I think that shocked the alumni even more. But, for those of us who have been living on college campuses all this time, it was no great surprise. The important thing I think was that suddenly the woke, progressive, so-called Progressive Left, and their strange confederates, the Islamists jumped the shark and behaved so outrageously that the big donors and the alumni finally noticed. |

| 6:40 | Russ Roberts: So, should college campuses ban those pro-Hamas rallies? Should they ban those placards? Should they ban those chants? Should they punish students who celebrate the martyrs, as George Washington University had a campus building at night that had a large sign projected on it, 'Glory to the martyrs,' in the aftermath of October 7th? Should those be protected forms of speech on college campus or should they not be? Niall Ferguson: Well, we have two systems in the United States, the systems or the system of the public universities where there are, by and large, clearly established first Amendment rights; and then the system of the private universities. And, the private universities can define free speech as they wish. And there's some variation from state to state, but that's broadly the way things are. And so, if it comes to, I don't know, the University of California Berkeley, it's fairly clear that those kinds of statement, no matter how odious they might be, are protected. Universities that are private, like, say, Stanford where I'm based, have the option of restricting speech if they have their own rules that say it's unacceptable. Now I'm, broadly speaking, a free speech fundamentalist. I take the Enlightenment position that free speech applies especially to the things people say that I dislike and might be tempted to silence. We just have to accept that in a free country, everyone, including undergraduates, has the right to express obnoxious views. There are limits on what they can do. They can't explicitly threaten individuals with violence. And, I think it's debatable how far explicit statements of support that recognize terrorist organizations are okay. But by and large, I'm prepared to put up with a lot of obnoxious speech as part of the price of true freedom. And, I think it would in fact be a great mistake if conservatives, after years of complaining about hate speech rules being used by the Left to censor the Right, now said, 'Well, it's our turn. We're going to start censoring you.' I think that would be a very depressing turn of events. I know there are some people who are drawn to that kind of solution, but I don't think it's the right one. I think it's better to ask the question: What have we been doing wrong as educators that, in the wake of hideous events that in some ways resembled the Holocaust because of the sadism and hideous nature of the acts that were perpetrated, what have we done that has so skewed the younger generation's sense of perspective that in the aftermath of those events, they're more likely to express support for Palestinians than for Israelis? Because, I can deal with there being students who express support for the Palestinians. That's fine. But, I find it shocking that there were relatively so few students willing to express outrage at what had been done initially to Israeli civilians. And of course, for there to be more than 30 Harvard student associations prepared to publish a statement justifying Hamas's acts of terrorism--that really illustrates that something's gone terribly wrong with our education of the generation that's currently in college. |

| 10:39 | Russ Roberts: Well, a lot to say, of course, but let me just ask this: Much of the loss of true intellectual discourse on American college campuses is cultural rather than legislative. Right? The 60% of the students surveyed by Heterodox Academy that you mentioned earlier who found themselves uncomfortable saying what they felt or self-censoring, that's not in response to a Draconian or hypocritical speech code on campus. That's the culture that has emerged from a variety of complicated factors. And, it's not clear to me how universities should respond to that cultural reality. Now, we'll talk about the University of Austin in a minute. I'll ask you about that. But the first thing I just want to observe is that that strikes me as equal part of the problem that your dislike and mine of where the moral compass pointed in the aftermath of October 7th. An equally disturbing thing is that campuses are simply not places of intellectual discourse anymore, and frequently places of political activism. But, let me ask a different question. You didn't--you're a free speech fundamentalist. I sort of am. I'm getting a little less fundamental. I recognize that, as a Jew, my tribal identity may be affecting my views on this. But, when campus groups rally and intimidate people--we are seeing this on the street with the posters of kidnapped Israelis that are being torn down. The people doing that are doing it often with delight, and if people try to restrain them, they are being stopped with the threat of violence. Do you make any distinction between a rally--which could be called a mob in certain settings--and a letter to the editor, a classroom, a set of remarks, a particular reading that might be assigned? Does physical presence make a difference there? And, I'll just add one more piece to it. Brandeis recently, and I think another college, has banned a couple of groups that they view as inciting or encouraging or justifying violence against Jews or Israelis. Should campuses do that on those grounds that there's a physical nature to a rally that is different than, say, a letter to the editor? Niall Ferguson: Well, there are, and I think should be, clear rules about this kind of thing. And, part of the problem is that the Progressive Left has very deliberately made it difficult to communicate those rules by using phrases like, 'Silence is violence,' or, 'Words are violence.' Violence is violence. It makes a huge difference if people march through a campus with placards and chants, and if they march through that campus and then engage in physical aggression towards other students. That second form of behavior is absolutely clearly out of order. And, any student who engages in that kind of behavior--and it doesn't need to be full scale beating--just pushing and shoving is, I think, clear grounds for disciplinary action. And, that has happened on a number of campuses. And we've all, I'm sure, seen video clips of behavior that ought to, in my view, have got the students involved--the students responsible for the aggression--expelled. So, I think we need to remind Generation Z--the current generation of students--what exactly is okay. A peaceful protest, no matter what the cause, is something that we can put up with at a university in a free society. But, if it shades into violence, or indeed the threat of violence--which I think is an extremely important distinction--then I think it's appropriate for university authorities to intervene. The language of safety has become, again, a source of confusion. And Russ, I want to make an important point. One reason that young people are confused is that for most of the last 20 years, a quite interesting and, I think, dangerous ideology has permeated academic life. And this ideology--which cloaks itself in a bland language of diversity, equity, and inclusion, intersectionality, minority rights--this ideology deliberately creates confusion by establishing a hierarchy of victimhood--which, Jews are very low down--and implying that the different identity groups in the hierarchy should be subject to different treatment. There was a lecturer at Stanford who, in the immediate aftermath of the events of October the 7th, in the course of more than one class, asked the Jewish students in the class to stand. And made them stand in a corner of the class making the argument that their identity as Jews required him to subject them to this particular humiliation. That should have got him fired immediately, in my view, because that is a grotesque abuse of the position that any instructor has in a university. But the problem is that a generation of activist professors have taken it upon themselves to blur the line between politics and science, or politics and the academy, and use the academy for explicitly political purposes. That's something which, in my view, is a profound violation of the fundamental norms without which a university can't function. Max Weber said this really well over a century ago: There should be a clear distinction between politics as a vocation and science or academic life as a vocation. We've forgotten that and we've allowed this radical generation of activist professors to abuse their position and engage in politics, in the classroom. That's something that has to stop, in my view. Russ Roberts: Very hard to monitor that, obviously. And, again, I think culturally it has to be a shared norm for people who at least allegedly are interested in the truth. |

| 18:02 | Russ Roberts: But I think--you know, part of what has damaged the humanities in America, and I assume elsewhere in the West, is a belief that academic life is a form of politics rather than truth seeking. I know quite well that truth seeking is often forgotten and it's hard to adhere to, but at least the official idea of a university is to encourage the pursuit of truth. And, in the postmodern era where truth is perhaps part non-existent in the minds of some, the natural result has been a proliferation, especially in the humanities, of political activism. And not just hiding it but being proud of it. And, I think that's part of the problem. Do you agree? Niall Ferguson: Unquestionably. I think overt political discrimination became something that was tolerated at department meetings during the 12 years that I was at Harvard, and I know that it goes on elsewhere. It's one reason that the academy has become politically more or less monochrome with only tiny percentages of professors identifying as conservative. And so, there's a fundamental problem of political skew that's made worse by the fact that liberals have hired illiberals. People who call themselves progressives are in fact profoundly illiberal, and regard themselves as entitled to engage in this kind of political activism and discrimination--which includes discriminating against students who don't take the right political line in class. So, this problem which finally burst into view for many people in October of 2023 has been a long time in the making. And, it will be extremely difficult to undo the damage that has been done, because once a department has been taken over by people who see politics as their true vocation, good luck getting it back because those people are extremely hard to dislodge. They have tenure, they will hire only people that they're ideologically aligned with, and they will pursue their goals quite ruthlessly. This is Control of the Institutions 101. |

| 20:19 | Russ Roberts: Let me go back to where I might be less of a fundamentalist. I want to make it clear, I have no problem with people criticizing Israel, demanding a ceasefire. I might find it immoral to do that without also demanding that the hostages be returned or many other pieces of that, but I have no problem with that. I have no problem with people criticizing the United States's role in supporting Israel, doing that from America. But, I want to see if you share this insight I heard from Tom Palmer of the Cato Institute and the Atlas Network, which I used to disagree with. This is where I'm a little less of a fundamentalist. He argued that when a group--a group, not an individual--when a group advocates for a movement that would eliminate free speech, that is the communist. For a Soviet communist marching in the 1970s or 1980s, or a Nazi, say, marching in Skokie or trying to march in Skokie,a Jewish neighborhood, a highly Jewish neighborhood outside of Chicago. Tom argued that if this group does not believe in free speech for others, they should not be able to use the protection of free speech to advocate their agenda. And, I used to disagree with that. That's where I'm a little more open to restrictions. And I think the challenge for college campuses today is that Hamas and some of the Palestinian support we're seeing is fundamentally encouraging and celebrating the death of Jews, not just a change in, say, Israeli foreign policy. I don't think colleges should be in the business of trying to figure out carefully who has crossed that line or not, but it may be something like, 'We know it when we see it.' So, I don't know if that should fall into that category, advocating or being close to advocating violence against other groups. But, I'm curious what you think of this idea that certain groups should forfeit free speech protections because they do not believe in free speech themselves and they are advocating for a world without it. Niall Ferguson: This is an argument that Hayek addresses at the end of the Constitution of Liberty, which has some quite interesting reflections on the problem of the university in the late 20th century. At that time, the great threat to academic freedom that Hayek discerned came from planners, both in the public and the private sector, who wanted to control the direction of research. That was his great preoccupation. But he does have a page when he says that it would be strange for an institution in a free society to give tenure to a communist. And, I think that's a sort of version of the same point: that, if you show a tolerance of intolerance--this is a kind of Karl Popper type argument, too--then you are really digging a grave for your own free society, or at least you are handing a shovel to the grave digger. Now, my sense is that the danger for any university system of governance is if it has to make decisions about what associations the students can and cannot form. And, I'm sure there isn't an administrator at Stanford who would tolerate a Ku Klux Klan march through the campus, but they've tolerated pro-Palestinian demonstrations which included pro-Hamas signs. That seems like an inconsistent position. I think if you're going to tolerate people chanting support of Hamas, you should be ready to tolerate people chanting support of the Klan. That's, I think, the problem that we've ended up with. There's a double standard. And I think a university has to choose. It either believes that students have a right to say odious things, but then they have to have a right to say odious things on the Right, too, or it clamps down on organizations that take views that are incompatible with a liberal society. Now, in thinking about how to redesign university governance, which I've spent rather a lot of this year doing, I've arrived at two very, I think, important positions that are somewhat differentiated from what is normal at a university today. I do not think it's appropriate for a university as a corporate entity to take political positions one way or another. I don't know why the presidents of Harvard, etc., feel impelled to issue statements about political events, but they started doing it around other events--think of 2020 in the wake of the killing of George Floyd. And that, of course, led them into a situation where they were expected to say equally forceful things after October 7th; and when they didn't, they looked absurd. The reality is that college presidents shouldn't be making statements of that sort because universities are not newspapers. They shouldn't have an opinion page. Universities are there to pursue truth. Veritas is the Harvard motto, and we need to remind the universities that their job is to pursue truth in all the different disciplines where universities are active. That's point one: Shut up about politics, all you presidents. Of course, it's fine for faculty and students to express their political views, but they do so in individual capacity and they don't speak for the institution when they do it. A second point: It is, I think, important that undergraduate associational life be free. The freedom of associations is as important as the freedom of speech, and students should be able to form societies without being treated as children by presidents and professors. So, there needs to be a clear separation between what universities do and what students do in their associational life. This has also been forgotten recently. Think of how Harvard tried to shut down the final clubs. In my view, as at Oxford, where the Oxford Union invites outside speakers, the invitation of people from the political world should be a matter for independent student associations. When the Oxford Union invites this or that person to speak, it's not doing so in the name of Oxford University, but in the name of the Oxford Union. So, I think that kind of separation--that institutional separation of the university from the political activity of students and the professors--is what we badly need to get back to. It's not difficult. We had these institutional norms before, but they got forgotten by a generation that felt it was in academia to pursue political goals. |

| 27:24 | Russ Roberts: Well, as a college president, I feel very strongly as you do that our college, Shalem College here in Jerusalem, should issue no political statements, whether that's on judicial reform, which was the hot button issue here in the country before October 6th, or what Israel is doing geopolitically and strategically in prosecuting a war in Gaza. Of course, as individuals we could express opinions about the morality of any of that, but certainly I don't think colleges should take a stand. I think the challenge is--you say we should remember those norms or bring them back. They're very hard to bring back. We had an episode here on the program on the notion of obedience to the unenforceable. And, speech in the classroom and speech at work and speech in one's own dining room, it's very hard to enforce. And, in general, it's these cultural norms I was referring to earlier that have changed and made people, say, self-censor or uncomfortable. It's very hard to say, 'Now, that's a mistake, folks. Let's not judge the people around us. Let's give them a chance and don't make them feel uncomfortable.' So, it's very hard to get the genie back in the bottle and I'm very worried--well, actually quite pessimistic--that that can be regained. It would take a revolution both in how colleges see themselves and in the daily back and forth that exists currently on campuses that has moved in a particular direction. I'm not sure there's much you could do about it. I don't think free speech codes or more Draconian regulations in favor of free speech are going to work. And, while I think it is essential--and we believe here at Shalem it is essential that people feel free to say whatever they like without censure. Anybody can be disagreed with using facts, civil argument, and should be, and that should be conducted respectfully; and that's what we do here or try to. And people who fail that test, we're going to talk to them about it and say, 'That's not appropriate for who we are.' And, that's how the unenforceable grows. It's how we get the respect for discourse that I think is the lifeblood of intellectual and educational life. I think it's going to be very hard to get it back. Niall Ferguson: Well, part of the problem is that once, as I mentioned, an institution, or for that matter, a department, has in a sense gone over to the dark side of engaging in politics as a vocation as opposed to scholarship, it is indeed hard to get it back. And, after 12 years at Harvard, seven years at Stanford, I finally came to the conclusion that the existing institutions were not really reformable, certainly not in my lifetime; and that was one of the motivations for creating a new University at Austin, the belief that we had to start over. And, in starting over, we have the opportunity to rethink the fundamental problems of academic governance. I think part of what's exciting, and you've had this experience, too, at Shalem, is creating a new institution that allows you to rethink the operating system itself. Academic governance is a strange phenomenon, and it took me a while to appreciate that almost all universities have the same institutional defect, which explains why they've so easily ended up being politicized and captured in the way that they have been. And that is that there is in effect an executive branch, which is the president and the provost and all of that--the bureaucracy. And there tends to be something like a legislative branch, which can be the board of trustees--the upper house--and the tenured faculty--the lower house--something like that. What they don't have is a judicial branch. I haven't been able to find a college anywhere that really has a judicial branch. And, if one looks at the U.S. Constitution as a model, that's a problem. Because if in a university the president decides to go down an illiberal path, or the trustees decide to go down an illiberal path, or the tenured professors do, even if there is a very clear set of principles--like, for example the Chicago principles on academic freedom--there's no way of upholding them because you can't go to a court and say, 'Look, they're violating the Constitution.' So, at the University of Austin, we've designed the Constitution to be much more like the U.S. Constitution. There is something like a Supreme Court and there is a very explicit set[?] of rights and obligations that are spelled out in the Constitution. There's a kind of Bill of Rights that applies to people at the university. And my hope is that that means when anybody is tempted to break the rules, there'll be a way of checking them simply by appealing to that adjudicative panel as I've called it. I'm hoping it won't be too busy because I'm hoping that quite quickly it will be clear that breaking the Constitution isn't okay. If you look at Chicago [University of Chicago--Econlib Ed.], which people often hold up as a paragon, they do have a quite impressive set of principles of free speech. But they aren't upheld, because if you ask the question, 'Can you speak freely in class?' to people at Chicago, they give much the same answer that people do at Harvard and at Stanford. There aren't huge differences. Students self-censor, they feel they can't speak their minds for fear of what their contemporaries will say. So, I'm not sure that the principles at Chicago are really honored other than in the breach. We've got to have enforcement mechanisms, and my hope is that by redesigning academic governance, we'll set an example that perhaps eventually others will follow. Of course, they'll only follow it if we really succeed in attracting brilliant students and then brilliant faculty to teach them. Once we establish that we are for real about free speech--that you can come to a classroom at the University of Austin and speak without fear because there are rules that will prohibit--we'll have a Chatham House ruling passed that will prohibit anybody saying that X said Y, because you can't under the Chatham House Rule attribute something that's said to an individual. So, by having meaningful rules that can be upheld, I think will create a radically different atmosphere; and that ought to be attractive to the kind of adventurous spirits that are, in any case, most likely to bet on an entirely new institution. Russ Roberts: Yeah. It's a fascinating question of whether a constitution for an institution like that can help create that unenforceable culture, even though some of the rules might be enforced. Culture itself, for an institution or a company or a family for that matter--it's hard to have rules--and it will be interesting to see--meaning, it's hard to enforce them. If you don't have the will to enforce them, they become essentially guidelines rather than rules, and that's the risk. Niall Ferguson: I'm an optimist, Russ, because we ran two summer schools, which were really experiments, to see what would happen and to give students a chance to come and study what we call forbidden courses. We made sure that the courses were just the kind of thing that you wouldn't have encountered at Harvard or Stanford. And I have to say, I was completely bowled over by the enthusiasm of the students. It's hard for people our age to imagine what it's like to be 18 now and to be sitting in class wondering if you say the wrong thing, will it end up on TikTok, and will that be the end of your entire life? We really struggle to imagine the social and cultural pressures that today's students are under. But if you give them a sense that those dangers don't exist, that they really aren't going to be denounced, that the institution will in fact discipline anybody who tries to be an informer, they really love it. And, I'm actually filled with confidence that, rather like the prisoners in Fidelio, when students are let out into the fresh air of freedom, when they actually experience uninhibited discussion, they enjoy it so much that the culture very quickly changes. I mean, the good news is--this is one of the best things about the human species--is that cultural norms can change. You just have to set different institutional frameworks with different incentives. I always remind people of the great experiments that were run in Germany and Korea: Let's give some of the Germans communism and some of the Germans a Christian democracy. And, within an incredibly short time, the two cultures have diverged, and even more radically in Korea. So, if you create the institutions of freedom in an institution like the University of Austin, you'll attract the people who are attracted to academic freedom and then as they practice it, it will become distinctive and self-reinforcing. So, on this, I am an optimist. We're much less the prisoners of cultural norms than we think. We are the prisoners of incentives. And, right now the incentive at Harvard or Yale or Stanford is, 'Shut up, don't say anything that'll get you into trouble. Don't antagonize the professor. If you want the A, don't say anything conservative.' Those are the incentives. But, if you take those away, the same smart students will behave, I think, quite differently. Russ Roberts: Well said. And, I wish the University of Austin great success. And I really appreciate you saying 'people of our age' as if we were similar. |

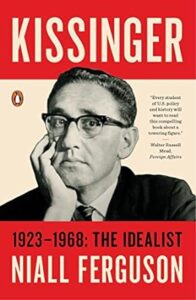

| 37:08 | Russ Roberts: So, I want to pivot here. I want to introduce your work on Henry Kissinger, which is, to me--your first volume was a thousand pages. How many volumes is it going to be? Niall Ferguson: Well, I have promised myself to do just another second volume and done. That's an enormously difficult undertaking because so much happened even in just the years that he was in government from 1969 through to the end of the Ford Presidency in 1977. So, it's a really tough undertaking. I've written 12 chapters and I don't feel anything like halfway. So, you find me on your podcast actually in full authorial crisis with vast amounts of material and a sense that it's almost beyond me. Maybe AI [artificial intelligence] can do this, but I'm not sure my intelligence is up to the effort of distillation. I'll get there in the end because I remember feeling this way about the Rothschild book, and that sense that you're drowning in material is actually a necessary part of the process of historical imagination. You have to feel really confused and overwhelmed before you finally figure out what happened. But, yeah, that's what I'm trying to do. And, yeah, it will be another long volume. I'll try and keep it under a thousand pages if I can. Russ Roberts: So, the first volume ends in 1968. In 1973, Kissinger plays a pivotal role in the Yom Kippur War. Talk about his role there; and I want to then turn to the question of its relevance for the current moment for both Israel and U.S.-Israel relations. Niall Ferguson: Well, I'll be brief because this is a work in progress. I haven't actually written that chapter yet, though I've done a fair amount of thinking about it. In many ways, October 1973 and the subsequent months are Henry Kissinger's finest hour--the moments at which he shows his greatest skill as a strategic thinker and a practitioner of diplomacy. Of course, it starts--and this will sound familiar--with an intelligence failure. Everybody is surprised, including the Israeli government, but the United States intelligence agencies and State Department are surprised, too, when Egypt and Syria attack Israel. And, this was definitely not something that was foreseen by the U.S. government. But, with extraordinary speed, Kissinger adapts to the new situation and sees an opportunity to break out of the deadlock that there had been since his coming into government in January 1969, in the Middle East. And, he does a couple of things that are really impressive. In the course of a quite-difficult, inside-the-Beltway, wrangle, he makes sure that Israel gets enough military aid not just to survive, but to turn the tide of the war--but not so much that it completely destroys the Egyptian and Syrian armies. The war stops after just 19 days. And the most important thing about that is that it's easier to stop a short war than one that's lasted longer. Memo to all those dealing with the problem in Ukraine: that war has gone on so long that it's really hard to stop. So, they stop the war. And then an enormously complex process of negotiation unfolds, which came to be known as Shuttle Diplomacy because he'd involved Kissinger shuttling back and forth between Egypt and Israel, and Syria and Israel, and Saudi Arabia and Jordan, and he just covers the region in an astonishing crisscrossing network of flights with occasional returns to the United States. And a trip to Moscow that's pivotal. I'll make one final point. I don't want to give a long and tedious lecture. There's a moment when it looks like the Soviets are going to intervene and wreck everything--intervene on the Arab side. And, at that moment--with Nixon more or less out of it, as Watergate began to destroy his Presidency and he sought solace in alcohol--Kissinger makes the decision, with a small number of other officials, to go to DEFCON 3 [Defense Readiness Condition]: to raise the level of military preparedness, a signal that is sent to tell the Soviets, 'Don't you dare.' And it worked. The Soviets backed down, and it's a turning point in the Middle East because it represents, really, the reduction of Soviet influence in the Arab world for a generation. From that point on, Kissinger is able to work on a very elaborate process, the first important breakthrough of which is an Egyptian-Israeli reconciliation. It's a fascinating performance, not least because it must have taken such stamina to do it. But, I think there's a lot that we can learn from it today. And, I guess that's what you're about to ask me. |

| 42:40 | Russ Roberts: Well, I want to just give listeners a little bit of background. Part of this interlude, besides taking advantage of your enormous knowledge of that particular moment in history--I'm sure you'll gain more before the book comes out--but, in trying to give listeners a richer picture of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Israeli conflict with its neighbors, the 1973 War begins with a unexpected attack. As you say, an intelligence failure. Syrian tanks come across the border in the north of Israel, and Egyptian tanks crossed the Suez Canal. Easy to forget that the entire Sinai was Israeli territory in the aftermath of the 1967 War. Israel is unprepared for this attack, and it becomes clear that the very existence of the State hangs in the balance. The joke--it's not a joke--that Israel can only lose one war: The Arabs can lose many, but if Israel loses one, it's over. Israel fights back desperately, turns the tide with the help of U.S. munitions and support. But, at a pivotal moment in that reversal, Israel has the Third Army of Egypt surrounded--enormous piece of Egyptian--the Egyptian army. And, if I remember correctly, American pressure, not for the first time, tells Israel, 'Don't do anything with--let them go.' And, that does set the stage. Even though Israel, quote, "wins the war," it is seen widely as a redemptive moment for the Arab world, meaning that they regained their dignity and saved face after the 1967 defeat. And, this allows Sadat to make peace with Israel in, I think, 1979, if I am not correct--1977 or 1979. Niall Ferguson: After Kissinger had left office. But, the path to peace was well established by the end of the Ford Administration. It's in the Carter Administration that this actually gets done. But, I think that's right. And so, there's a very important insight here which I'd like to suggest. The first is that, by comparison with today, although it was a terrible blow and the death toll from the Israeli side was extraordinarily high, the war was a war that revealed Israel's fundamental strength. The tide turned very rapidly. And as you say, Egyptian defeat could have been much more crushing had it not been for Kissinger essentially saying, 'Wait, we can make much more of this if we show restraint than if you wipe them out.' And, that's an extremely important moment. I feel as if today Israel is in a weaker position--and so is the United States--or at least it acts as if it is because there's nothing, as far as I can see, to compare with Kissinger's DEFCON 3 [Defense Readiness Condition, Level 3] move to keep the Soviets out of an intervention. Where today, the Biden Administration seems very loath to deter Iran from continuing to encourage its proxies to attack Israel. Two aircraft carrier strike groups have been sent to the Eastern Mediterranean, but the language that has come out of Washington over more than five weeks now has been less than muscular. And, these limited strikes on what seem largely unimportant Iranian assets have not conveyed, in my view, to Tehran that if Hezbollah is unleashed from Lebanon against Israel, there will be major consequences for Iran itself. So, there are two very interesting differences to me 50 years on. Number One: Israel's position seems weaker today than it was then just in terms of military capability, but also in terms of international legitimacy. And, the United States seems much less capable of using its power to deter the real threats to Israel--which are not terrorist organizations, but are Iran, and I think also to some extent Russia. Because one must bear in mind that Iran is only part of a kind of axis of ill will that now exists that extends to Moscow, extends to Beijing, not forgetting Pyongyang. These countries are coordinating their efforts in Ukraine and in the Middle East in ways that I think are in many ways more problematic than the Cold War dynamics of 1973. |

| 47:42 | Russ Roberts: Let me go back to the Third Army and Kissinger for a minute and then we'll come back to the present and talk about the United States and Iran. As you point out, the Soviets were threatening to get involved. The Soviets were arming Egypt--again, for historical context. And, my understanding has always been that the reason that the United States restrained Israel was out of fear that not just Egypt might suffer a humiliating defeat after their success at the beginning of the war, but that the Soviet Union would see such a defeat as a defeat of themselves and would come into the war threatening World War III. And, I've always assumed that was Kissinger's motivation. Not a long-picture view of a future potential peace between Egypt and Israel. Wasn't it merely the realpolitik of reducing the risk of a Soviet-U.S. conflagration? Niall Ferguson: I don't think so, although, let me reiterate, this is work in progress. Kissinger had said long before the crisis blew up that the goal of U.S. policy was to exclude the Soviets from the Middle East and establish American dominance. Which was a bold goal, considering that the Soviets were pouring weapons into the Arab world and were even sending pilots to fly some of the planes. So, the stated goal was to get the Soviets out of this absolutely pivotal region and reduce their influence over it. And, that was achieved. And I think it was achieved with a bluff. DEFCON 3 was really a bluff. It made sense because Kissinger rightly calculated that the Soviets had too much to lose from other aspects of détente to risk war over Israel and the Arabs. I think there was another piece of this which was equally important. Kissinger had underestimated Sadat and had paid too little attention to what Sadat was trying to communicate to him prior to October 1973. And once the war broke out, Kissinger understood with a flash of insight that he'd underestimated Sadat. And, Sadat was using the war as a way to reset the diplomatic table by establishing some symbolic respect and dignity for the Arab cause as a prelude to a negotiation that would be far more likely to yield results than anything that had gone before. And, I think it's very interesting how quickly Kissinger sees that and gets onto Sadat's wavelength. That's really the most important thing that happens with the Shuttle Diplomacy. What Kissinger gets wrong was he underestimated, was the effect of an oil embargo on the global economy. And so, although he did his best to connect with the Saudi regime, that was a non-meeting of minds by comparison with his relationship with Sadat. And, Kissinger including--and his other colleagues in the administration were given a real economic shock by the oil embargo, which quadrupled oil prices and of course hit the United States economy and the economy of the whole world extremely hard. So, I'm not going to, in my depiction, present him as some unassailable genius. Martin Indyk, by the way, has a very good book on Kissinger's Middle East policy, which is full of insight as you'd expect from somebody with so much diplomatic experience. And he also gives Kissinger very high marks as a diplomatic player, though he concludes, I think, by saying that Kissinger underestimated how very difficult things would be if the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization] took over the role of representing the Palestinians. And, Indyk suggests that the opportunity to make the Palestinians a Jordanian problem was lost. And, in that sense, what Kissinger achieved had this fundamental flaw which would become more and more apparent with the passage of time. But, I guess those are the outlines of the story that I'm going to tell. Russ Roberts: Have you seen the movie Golda? Niall Ferguson: I haven't seen it yet, and I'm hesitant to see it. Part of the problem about doing history is that historical novels in Hollywood are your enemy--because your brain doesn't compartmentalize. It kind of unwittingly puts all data into the same hopper, including fictionalized and dramatized data. So, I'm resisting the temptation to go and see it. Russ Roberts: I happen to be at the world premiere here. It was shown outdoors with Helen Mirren in attendance. In Golda, a bowl of soup plays a critical diplomatic role. I suspect that is not in the archives. |

| 52:67 | Russ Roberts: But, let's turn to the question of the U.S.-Israel relationship. I actually--I'm a little more comfortable with the Biden Administration simply because I don't know what they've said behind the scenes. I agree with you that their public remarks have been somewhat--have tempered their muscular show in the Mediterranean with the aircraft carriers. But, I think the real challenge here, and I think it's a challenge for the West generally, is that the West doesn't really like to kill people. And, that's a great thing. And, they don't like their own children to die, which is also a great thing. But, we look back at the appeasement of Hitler in 19'--with Chamberlain in 1938 and beforehand. The appeasement of Iran, offsetting the Biden Administration's aircraft carriers or the eagerness they seem to have to give money to Iran--not a small sum, billions of dollars. I don't know what that's going to purchase. I can't see the West facing Iran in any serious way. Do you disagree? Niall Ferguson: I don't disagree. I think what's strange about the Biden Administration that future historians will have to figure out is that on the one hand, it continued Donald Trump's policy towards China, and if anything ramped it up. But, on the Middle East, it entirely broke with what the Trump Administration had been doing. And I find that somewhat puzzling because the Trump Administration was quite successful in the Middle East. The Abraham Accords were a great outcome, and the direction of travel was clear towards further reconciliation between Israel and the Arab states, marginalizing of the Palestinians, and then isolation of Iran. Iran's economy was crumbling. And then, along come Team Biden and say, 'We're going to revive the Iran nuclear Deal, ease the economic pressure on Iran.' And, I never understood why they did that, because it seemed to me: A., that the deal was dead and not capable of being resuscitated. B., that the Iranian regime was clearly going to act in bad faith and continue channeling resources to its terrorist proxies around the region. And, given how much we heard about collusion with foreign powers during the Trump Administration, there seemed quite considerable evidence of collusion between elements of the Biden Administration and the Iranian regime. You couldn't read about this in the New York Times unless you read Bret Stephens's one column on the subject. But I think there's some real work to be done by future historians on what exactly Rob Malley was doing and what exactly they were willing to concede to Tehran to try to bring back from the dead, the nuclear deal. Look: the problem the Biden Administration has is that it's really bad at deterrence. It failed to deter the Taliban, who ran amok as the United States withdrew from Afghanistan. It failed to deter Russia--entirely failed in 2021 to deter Russia--from invading Ukraine the following February, and it's failed to deter Iran in 2023. The next thing it will fail to do is to deter China. And, that's the thing that worries me a good deal, that we could have one more crisis before this Administration leaves office, and that will be in the Far East over Taiwan. So, the crisis in Israel, the crisis in the Middle East--which is not over. I mean, I want to emphasize that this can run for months and months. You know this, Russ, but not everybody listening may be aware of it. The focus is all on Gaza at the moment, but there's a lot of fighting and conflict going on in the West Bank. There's a lot of fighting going on on the Lebanon border. This thing can really go in a number of different and quite alarming directions. But, it's only part of a broader global crisis, I would say a world crisis, in which the United States confronts an increasingly well-organized axis of powers, of which by far the most economically important is China. But, Russia and Iran are doing a lot of the dirty work. And, this movie, this global movie, has another year to run. |

| 57:40 | Russ Roberts: Well, while the Biden Administration did not deter around from unleashing the Hamas attack, they have been successful in discouraging a full-fledged Hezbollah counter-attack. There is war on the northern border of Israel. Niall Ferguson: Is that right, though?[?] So, one possibility, Russ, is that Iran has concluded it doesn't need to unleash Hezbollah because it's already achieving so much with the backlash against Israel that there has been in the past five weeks. And, that what Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad did was to put Israel in a position in which it could do nothing other than to intervene in Gaza, and that that was bound to generate a backlash. Because all around at the Western world, there is a new generation of younger voters who have been very successfully wooed to the Palestinian cause and impregnated with anti-Zionist and in some cases antisemitic ideas. So, if I were in Tehran, I wouldn't be worried about those aircraft carrier strike groups. We know--we can read it in the New York Times--that Joe Biden is afraid of getting into a war with Iran. He has no intention of using all the military assets that he has in the regio. Iran is getting exactly what it wanted. It's reactivated the Arab street, aligned itself with that street, and put Israel in a position of extreme international vulnerability. Why spoil that by unleashing Hezbollah and risking that sympathy switches back to Israel? They don't need to. |

| 59:19 | Russ Roberts: Let's try to end on an optimistic note. Slightly discouraging observation there. 1973 was a military victory for Israel, but it's widely seen here as a devastating defeat--enormous casualties given the size of Israel's population, a loss of faith in the government through the failure of security and intelligence that you talked about, that we talked about, and pushed Israel's politics to the Right for a long, long time. Destroyed, essentially, the Labor Party, the party that had founded the state and had ruled it until that point more or less. And, that allowed the rise of Menachem Begin, later Netanyahu and others, the rise of the Likud party. So, 1973 was a disaster for Israel, both in human cost and diplomatic failure. And, governmental consequences were significant. Political consequences were significant. But something wonderful came out of it unanticipated, which was peace with Egypt. A peace that has stood for almost 50 years and seems to be holding. Peace with Jordan--notwithstanding recent unpleasant remarks in my view from some various Jordanian spokespeople--Jordan shows no signs of being sympathetic to the jump-on Israel problem for us here. So, could there possibly be an aftermath to this current moment that would be positive? Niall Ferguson: I think there are reasons not to despair. First of all, I actually don't think the process that produced the Abraham Accords is dead. I think the Saudis are going through the motions because there's a limit to how far they can defy the mood of the moment. But, the underlying preference, I would guess, is when the time is right to resume the process of improving and ultimately normalizing relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia. I think the Gulf States generally have turned away--turned away a long time ago--from the Palestinian cause. They also turned really quite decisively away from the Islamists. That broad shift away I think also will continue: for reasons that are peculiar to each of the different states. But, I think from the point of view of Saudi Arabia, there has to be a better strategic future. And, that strategic future requires to rethink Saudi society, rethink the Saudi economy, and take advantage of the fact that there is one highly dynamic technological state in the region: and that's Israel. So, I don't think the structural forces that were moving the Israeli relationship towards improvement with most of its neighbors, I don't think those have gone away. I think much of what we're currently hearing from governments that you mentioned--the Jordanians, one might also mention the Saudis--I think all of this is in some measure for show and it does not reflect a profound change of sentiment. Secondly, whether you like him or not, Donald Trump looks increasingly likely to be the Republican nominee, and that means he has a roughly 50% chance--it might even be better than that--of being the President in January of 2025. And, he will be, as you know, Russ, only the second President in history to have two non-consecutive terms if that happens. The last one being Grover Cleveland-- Russ Roberts: Grover Cleveland. Niall Ferguson: Donald Trump is a figure who terrifies most academics, and yet from the vantage point of Israel--and we are focusing here on Israel's position--a second Trump term would be by no means bad. I think it'd be pretty bad news for Ukraine. I'm not sure how good it would be for Taiwan. But I think for Israel, it would be in fact a significant improvement: because there would be no more resuscitation of the Iran nuclear deal. There would be no more making nice with Tehran. The Iranians would then have to reckon with all kinds of uncertainty which Trump brings with him. And, I sense that this might in fact restart that process I talked about earlier which produced the Abraham Accords. So, I actually think within a relatively short space of time, Israel's situation could improve. How to play it? Well, I think the IDF is already doing a pretty effective job in Gaza despite all the hostile press and all the pleas for ceasefires and pauses and restraint. In fact, Hamas is being crushed. I think it's showing great and clever restraint with respect to Hezbollah. I don't think Israel should fire the first shot, should launch the attack against Hezbollah. I think that would be an error. I think, considering how disastrous the immediate aftermath of October 7th was, I'm impressed by the fact that Israel has come together as a society and the IDF is back to fighting clever. So, bad though things have been--and heaven knows they have been bad--there are reasons not to despair--and that, I think, is the note on which I'd love to end this conversation--with hope. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Niall Ferguson. Niall, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Niall Ferguson: Thank you, Russ. |

How can we create a radically different atmosphere at American universities? Easy, says historian Niall Ferguson of Stanford University's Hoover Institution--have meaningful rules about free speech, and ensure that they're upheld. As with humans, as with institutions: It's all about incentives. Ferguson discusses the current state of free speech on American campuses and how the new University of Austin when it opens hopes to safeguard freedom of speech. The conversation shifts then to the war in the Middle East. Ferguson draws on his work on the biography of Henry Kissinger and compares the present moment for Israel to the Yom Kippur War and the role Kissinger played in 1973.

How can we create a radically different atmosphere at American universities? Easy, says historian Niall Ferguson of Stanford University's Hoover Institution--have meaningful rules about free speech, and ensure that they're upheld. As with humans, as with institutions: It's all about incentives. Ferguson discusses the current state of free speech on American campuses and how the new University of Austin when it opens hopes to safeguard freedom of speech. The conversation shifts then to the war in the Middle East. Ferguson draws on his work on the biography of Henry Kissinger and compares the present moment for Israel to the Yom Kippur War and the role Kissinger played in 1973.

READER COMMENTS

Matt

Dec 11 2023 at 9:24am

This really is too much.

First he basically equates any “pro-Palestinian” actions as “pro-Hamas.” Then he comes right out and says the terrorists attacks on one day are very much like the Holocaust, a state-sponsored multi-year program to kill millions.

It is sad to hear all these “conservatives” who have whined for years about not being able to be openly transphobic now get all up in arms that anyone has an opinion other than theirs re: Israel.

Maybe try some empathy, as Kevin Drum does here:

https://jabberwocking.com/seeing-israel-through-young-eyes/

Luke J

Dec 21 2023 at 10:03pm

It is a ridiculous position to imply a person or group of people are transphobic and then suggest empathy as the way forward.

RFT

Dec 11 2023 at 7:42pm

Something feels missing from Ferguson’s answer at 0:22:00: that a university should either be a free speech absolutist or it must restrict any speech “incompatible with a liberal society.” The latter seems like is bears the same problems as any case for intolerance toward the intolerant.

When activist college students invoke the paradox of tolerance to deplatform guest speakers, my gut is always unsatisfied with their argument.

“To protect freedom of speech, I believe in restricting the speech of those who believe in restricting speech.”

For one, it seems like anyone who makes the above statement is liable to be interpreted as the very target of restrictions by someone else with even slightly different views (hence both parties in America taking turns pointing at each other as speech haters).

But mostly, I think the problem is that it goes against the stated appeal of freedom of speech for most people — that it’s a fundamental human right.

I’ll admit there is something appealing about the logic of not tolerating the intolerant. What appealing justification could a free speech opponent possibly formulate against their own censorship? After all, maybe this looming threat could make them see the error of their ways.

Using the same logic (I think), I get a very different kind of thought: “What appealing justification could an opponent of due process formulate against being treated without due process?”

But with this hypothetical, I feel like the question is thrown back at me: “Why do I believe in due process in the first place if I’m looking for an excuse to circumvent it?”

I don’t think such a question is nearly as rhetorical when framed for freedom of speech. For anyone in favor of intolerance for the intolerant with regard to liberal values, why believe in freedom of speech in the first place if you’re looking for an excuse to circumvent it? I’m open to ideas.

Shalom Freedman

Dec 11 2023 at 9:15pm

The discussion on the elite universities in the US on freedom of speech and freedom of inquiry did not to my mind underline strongly enough the danger the present situation constitutes to the future of the United States and the free world. If tomorrow’s leaders of the US have the closed-minded mentality displayed by those who could not condemn the horrible massacre that occurred on October 7 2023 in Israel the traditional character of the United States will be in deep trouble. The Palestinian narrative bought hook line and sinker by the fools of the now almost completely radical left points to a total lack of critical judgment and thinking, As to their improbable allies, the radical Islamic students perhaps something more might have been said about how they have brought to the West their culture of bullying mob intolerance.

Here I would connect the first part of the conversation with some of Ferguson’s remarks in the second part of the conversation. Ferguson speaks about Israel’s position in the present war on Hamas as being weaker than its position (in a political sense) than it was in the Yom Kippur War. But what is equally and even more important is that the position of the US and the free world is much weaker than it was in 1973.The United States is facing today an alliance however problematic of Iran Russia and the most powerful enemy China. It has behind it the experience of the failures in Afghanistan and Iraq. It does not need a land war in Asia that it does not believe it can win. Here Ferguson has a recommendation that seems to me disastrous.

Donald Trump thought differently from his predecessors and greatly helped Israel in many ways. This does not mean that he would do this again. More importantly his divisive immoral criminal behavior makes him unworthy of being President again. Neither Biden nor Trump should be the next leader of the free world. I really do not know if she has the qualities required to be a great leader, but it seems to me Nikki Haley presents the best hope for somehow bringing America to a better future.

I have in this comment touched upon and largely critically only a small part of what Russ Roberts and Niall Ferguson said in this truly first-class conversation. Their depth of knowledge and brilliance of analysis is apparent throughout.

Ajit Kirpekar

Dec 12 2023 at 10:42am

I am glad the discussion turned to whether free speech, even when it veers into the worst kinds of statements, should be tolerated on campus.

To answer the guests questions, for me, if a group of protesters wants to have a rally to celebrate the KKK or the gas chambers in Europe and as long as they do so peacefully, i think it should be permitted.

I take this position, despite the fact that I too would be horribly offended by those rallies, yet I acknowledge them as the price for freedom of speech. I think it’s the only way to be logically consistent. Otherwise, as soon as we decide x form of speech is “too offensive”, it opens the door for widening that to many other forms and pretty soon, we get the woke movement.

Natalie Cohen

Dec 12 2023 at 3:41pm

I too was surprised that Niall Ferguson seems to use “Hamas” and “Palestinian” interchangeably. Certainly Palestinians, notably women and children, have been used as fodder for Hamas and are not free to express their opinions. (Consider Malala, who was shot in Pakistan for daring to advocate education for girls. Or Mahsa Amini, who died in Iranian prison for failing to wear a proper hijab). Hamas is a declared terrorist organization, officially designated as such by the US, UK, Japan, Paraguay, New Zealand, Australia, EU and so on. Yet Palestinian civilians are victims too — and the humanitarian harm (on both sides) will take more than a generation to recover from, if then. No question that Netanyahu’s administration also silences dissent, and is committing atrocities against civilians. Using a term like “woke” in this discussion is clearly intended to be pejorative rather than instructive. Unfortunately we are stuck with a hardened “my way or the highway” social culture where hurling epithets and worst case, invoking generalized violence, is easier than recognizing terrorism for what it is or acknowledging innocent victims who want to live in peace and safety.

Thanks Russ Roberts for very interesting podcasts and willingness to tackle difficult and sensitive topics.

Chambana

Dec 12 2023 at 11:13pm

Wow. It has been a long time since a reputable historian tortured and stretched the truth to the point of pain like Ferguson just did. I would expect such half-truths and complete disregard of historical facts from an active politician, but not from a historian.

A naïve observer listening to Ferguson’s narrative may conclude that Biden is running Israel. According to Ferguson, it was Biden’s fault for not preventing October 7th attacks???

Those better informed, however, will recognize that Mr. Ferguson conveniently neglects a bunch of important details.

First, up to very recent Hamas has been a pet project of Bibi Netanyahu and his right-wing extremists who rooted for Hamas’ political flourishment so that they can kill any prospect of the two-state solution. Ample evidence shows how Bibi’s men busied themselves ushering cash in coffers from Qataris to Hamas, all the while neglecting real signals about Hamas’ plans.

This classic Bibi behavior is consistent with his earlier opportunistic escapades in which sandbagged Obama’s initiative to jumpstart the peace process. Back in 2010, Biden visited Israel only to hear an announcement from the Israeli Interior Ministry that it had approved 1,600 new housing units in East Jerusalem, an area claimed by the Palestinians. Any prospect of a serious plan died right then.

In another gem by Ferguson, he claims that Biden’s administration gave (presumably taxpayers’) funds to Iranians. The truth is that $6 billion in questions were proceeds from Iran’s sale of oil. The funds were strictly earmarked for food and medical needs and did not come from the US taxpayers. Yet, when you aim to accomplish a political agenda, it is convenient to forget such details. Btw, the administration immediately froze the funds in the aftermath of Oct 7th.

Lastly, Ferguson accuses Biden of cowardice for not having cojones to attack Iranians. I wonder what Ferguson would do? Perhaps bomb Teheran and then accuse Biden of (oil price) inflation when the Middle East shots down the pipes.

In the end, I was surprised Fergie forgot to extoll Kushner’s plan that solved the Middle East crisis.

To disclose my priors: I am a full supporter to Israel’s right to defend itself, but this truth torture does not bring any good to anyone.

Daniel Shapiro

Dec 14 2023 at 12:57am

Russ Roberts seems to endorse an argument that groups that would deny free speech to others on campus or if they got in power (e.g. groups supporting Hamas, Nazis, Communists) are not entitled to free speech rights on campus because they have forfeited that right by their advocacy of anti-liberal, anti-free speech views. I think this argument is deeply flawed for several reasons:

The argument would support banning or censoring not just groups like Hamas, Nazis, and Communists, but a significant segment of the American public who have anti-free speech views, in that they want the government to have the power to ban speech they find offensive misinformed, evil, etc.

College administrators cannot be trusted to decide which viewpoints should or should not be censored. If given the power Russ suggests they should have, it would very quickly slide into banning views administrators find objectionable, retrograde, ‘hateful,’ etc. Their behavior over the last few decades bears this out with the enactment of speech codes, bias response teams, so-called safe spaces, etc. It is odd in a discussion of the degradation of free speech norms over the last few decades to propose giving more power to administrators who have contributed to this degradation.

Mere advocacy of a totalitarian or anti-liberal viewpoint does not mean you have forfeited your rights. Forfeiture occurs when you have violated others’ rights or have made an actual, immediate threat to do so. I recommend David French’s recent New York Times Op-ed, “What University Presidents Got Right and Wrong About Anti-Semitic Speech,” who notes that there is no First Amendment exception for advocating violence and that there is also no exception for advocating genocide. French also cogently discusses the dividing line between free speech and harassment (not a point Russ raised, but worth mentioning anyway). https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/10/opinion/antisemitism-university-presidents.html?unlocked_article_code=1.FE0._owU.Pou8EIuQAmnE&smid=url-share&fbclid=IwAR3wqZ2yJV41-PiXm1ih9SVWxIqMR9Yq7qRqDSgG8W-NyWzFn4EWPRWR-TQ

Daniel Shapiro

Luke J

Dec 21 2023 at 10:14pm

I’m not sure Russ is endorsing such a view; more like reconsidering the merits of.

Speaking as a non-lawyer, I would imagine the problem with this view is that the 1st Amendment is a restriction on Congressional power without regard to the speaker or the speaker’s content.

That said, there are speech restrictions at local, state, and federal levels. Whether you agree with these or not, I would hope that calls for the annihilation of Jewish people would be met with the greatest reproof.

L. Burke Files

Dec 17 2023 at 11:47am

Naill and Russ, I was cheering along on the entire conversation until – that last thought that schools can reform themselves. Higher Education will never change unless the incentive structure is changed or the schools burn down and sink into the swamp.

Researching Operation Varsity Blues with two others, I came to the conclusion higher education is a corrupt cabal. – Link to BYU Law Review https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3336&context=lawreview

The problem begins with the accreditation bodies and processes. Accreditation needs to be scraped and redone or offered open accreditation. The current process places foxes in charge of the hen houses and writing their own performance reviews.

. There are too many laws for higher education. It is asinine when 45% of school budgets are spent on compliance issues.

Admission standards need to be clear and direct. If a school is admitting legacy students or offering scholarship for 500K for admission – say so. The tap dancing around who gets in and who does not screams fraud collusion and private selections. If the school is doing that, tell everyone; if not, and admission is based upon merit, tell everyone.

Kill off student loans backed by the Federal Government. If the schools want to recruit students who need financial assistance, more power to them. The schools should lend the money – not the taxpayer. The schools and the students both need to have skin in the game. Having the student borrow from the school aligns the incentives. So many students are admitted to schools for special reasons where they cannot compete. They enroll, find they are not prepared, and have to drop out. Now, they have failed and have substantial debt. This is a common outcome when the only skin in the game is the student’s guaranteed money from loans.

Endowments of universities need to be 100% transparent on investment selection and performance. Further, the Endowments act a tax-free hedge fund with one shareholder. They should be taxed on their profits. Further, both private and public schools need to pay property tax.

Boards of trustees have to engage in real governance. The tone is set at the top. If you pick a trustee for financial or political gain – so be it, but the school and the trustees must be held responsible for any and all mis and mal feasance. Being a trustee is not a plum; it is a responsibility, and it requires real work.

Just addressing accreditation – competition will seep into the market. Address the rest and higher education will be tossed back 50 years to when disagreement and debate were shared sports and vital to education.

Yet again another tour de force on EconTalk.

Thank You

Erik

Dec 18 2023 at 12:04pm

Excellent!

Luke J

Dec 21 2023 at 9:56pm

I’m curious what other people think about self-censorship on college campuses. To me it seems there is a spectrum of good-to-bad censoring: complete lack of inhibition is the extreme left, and silence about violence on the extreme right. Somewhere between are things like seeking affirmation from peers, feeling important, challenging group-think etc.

When college students report that they are not free to speak their mind, I wonder where on the spectrum these unspoken thoughts actually lay (lie?).

Nathan Emery

Dec 23 2023 at 3:46am

Ferguson makes a bold comment that the UAE has moved away from supporting terrorists needs to be challenged in relation to the Abraham Accords. Perhaps Ferguson takes the UAE for their words, without evidence, as their denials of supporting, for instance, the RSF in Sudan, or the relationships and protection of Hamas leadership in Dubai, all have irrefutable evidence to the contrary, amongst many more. I think Ferguson needs to deepen his knowledge on the subject instead of blindly supporting an initiative that seemed commercial without any promise of ‘peace’.

Steve Miller

Dec 24 2023 at 10:56am

On the problem of changing the ‘culture’ of universities, consider how one improves incentive alignment (aka addresses agency problems) in corporations. Align universities with their mission by changing university incentives and enhancing disclosures. This is especially true wherever tax dollars are used to support university budgets.

Examples to illustrate include:

Budget Incentives: 1) Eliminate funding for any DEI initiatives. 2) Universities must approve underwrite and bear student loan default risk. 3) Link (a significant portion of) state funding to metrics based upon student outcomes (e.g., return on tuition) in private sector jobs.

Disclosure Requirements: Require prominent disclosure of FIRE free speech rankings. This could be modeled after 10-K disclosuures and/or nutrition labels on food products sold at grocery stores. Require a standard set of disclosures (e.g., student-faculty ratio, tuition costs, FIRE free speech ranking, USNWR ranking, etc.) displayed in a standard way on university websites and all marketing material to students.

Robert W Tucker

Jan 1 2024 at 2:43pm

This episode started out discussing Kissinger and free speech during which time I enjoyed Mr. Ferguson’s perspectives. The podcast ended with Mr. Ferguson stridently superimposing his well known and, in my opinion, poorly supported biases. Russ did an admirable job of allowing Mr. Ferguson free reign while making it clear that he was well aware of the irrelevance of his digressions.

Comments are closed.