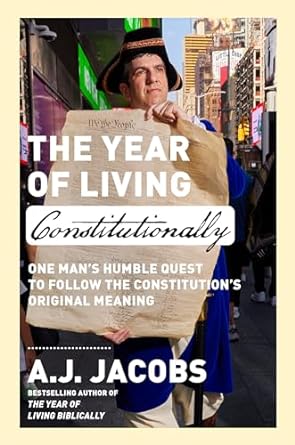

| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: April 16, 2024.] Russ Roberts: Today is April 16th, 2024, and my guest is author A.J. Jacobs. This is A.J.'s third appearance on EconTalk. He was last here in June of 2022, talking about all kinds of puzzles. Our topic for today is his latest book, The Year of Living Constitutionally: One Man's Humble Quest to Follow the Constitution's Original Meaning. A.J., welcome back to EconTalk. A.J. Jacobs: Delighted to be here. Thank you, Russ. |

| 1:04 | Russ Roberts: This is a seemingly silly book, but it's actually delightful and thought-provoking and wonderful, and not silly at all. But, the premise is a little bit unusual. So, tell us what you were trying to do in the time that you prepared this book, and how did you do what you tried to do? A.J. Jacobs: Absolutely. Well, thank you. Yeah, I feel it's a little bit silly, but also I tried to be not silly, so I don't mind that appellation. This partly is a sequel to a book I wrote many years ago that we've talked about on the show called The Year of Living Biblically, where I try to understand--I grew up in a very secular home and I tried to understand the Bible by getting in the sandals, walking in the sandals of our forefathers, and actually following the rules from the Ten Commandments, to growing my beard because Leviticus says I should grow a beard. And, I found that an amazing experience. And, I realized I had a bit of a similar feeling about the Constitution. I was shockingly ignorant of it. I had never read the Constitution from start to finish. Have you read it? I had not read it from to start-- Russ Roberts: Such an embarrassing question. Not only have I not read it, I haven't even thought about reading it. A.J. Jacobs: All right, I retract the question. I retract the question. But, every day I read another news story about how this 230-year-old document was having a huge impact on my life and millions of other lives. So, I thought: Well, one way to understand it would be to do what I like to do, immerse myself and walk the walk, talk the talk, carry the musket, write with the quill pen, quarter a soldier, eat the boiled mutton. And, it was--it was amazing; I got insights. And, my hope was that this would be entertaining, but it would also teach me how to look at the Constitution, how to interpret it, and hopefully that I would more optimistic at the end about our democracy, because it has been a rough few years, just with the fire hose of negative news from all sides. So, and that is what happened. I do feel more optimistic and empowered. But, it was an amazing experience. Russ Roberts: We're going to talk about some of those things that you mentioned, but I first want to just verify: you're still married, correct? A.J. Jacobs: I am. As of this morning. Russ Roberts: Okay. A.J. Jacobs: But, yes, I put her through the ringer with the Bible book. She's definitely very patient. Patience of Job. She wouldn't kiss me--I had a huge beard and she wouldn't kiss me for months. And this one also presented some challenges from whether it was quartering a soldier in our New York apartment, to having muskets in our apartment, to the smell of the candles, and etc. |

| 4:11 | Russ Roberts: Let's start off actually with--one of my favorite things is the quill. And, I want to know--you could describe the candles, too--what role did that quill play in your life for this past year? A.J. Jacobs: Well, I figure part of my goal was to express my constitutional rights using the mindset and the technology from when it was ratified. So, I thought, 'I'm going to give up social media as much as I can, and I'm going to write with a quill and old-style ink on parchment if I can, or just cotton rag paper.' So, I did. I wrote pamphlets. I handed them out in Times Square. That was my social media. But, what was remarkable was how writing with a quill--the experience itself--I felt was profound because it made me think differently. It slowed down my thoughts. I couldn't just type some acronym and press Send. I had to take out the pen, and it was like a waiting period for my thoughts. And, there were no dings and pings to distract me. I do think that there is--I don't think we should all go back to quills, but handwriting or just cutting off from the Internet completely while writing will have an impact on our thoughts, make them more nuanced, make them more deep. Yeah, so I am a big fan. And, I didn't write the whole book with a quill pen, but I did write large portions of it, and I found it wonderful. Russ Roberts: And you did occasionally sign a credit card receipt with it, as you recount--to the horror of your family. A.J. Jacobs: Yes. It was quite embarrassing for them. I took it out on the road because they had--actually, the laptop of the 18th century was a desk, sort of a slanted desk that you could carry around. That's what Hamilton had. So, I would take that as my laptop-to-go, and I would get out my quill pen, sign checks. And, I got people to sign a petition. That's one of my rights that I expressed is the right to petition Congress for the redress of grievances. Russ Roberts: This is a goose quill, it's a feather, for those of you who haven't seen it. Did you have to sharpen it from time to time? A.J. Jacobs: I did. Absolutely. I mean, I bought some pre-sharpened quills, but there are many-- Russ Roberts: Ugh. A.J. Jacobs: Exactly. Thank you. Russ Roberts: Shame on you, A.J. A.J. Jacobs: But I did learn, thanks to Ye Olde YouTube, I learned how to sharpen my own quill, and that is actually one of the--it's not a major theme, but a minor theme is the DIY [do it yourself] of 18th century. There's a lot that we don't want to return to from the 18th: it was sexist, racist, smelly, dangerous, antisemitic. But, there is some virtues that I think we should revive. And, one of them was this DIY: just being able to make your own ink and make your own quill. It just connected you to the physical world in a lovely way. Russ Roberts: I'm pretty sure that the quill is a connection between The Year of Living Biblically and The Year of Living Constitutionally, because I think the scroll of a Torah has to be written with a quill by hand-- Russ Roberts: and, it's a certain style of calligraphy. And it's actually quite beautiful. But, the idea of taking a feather of a goose and using it to create this incredibly human language experience--the written language of Hebrew from thousands of years ago--is quite amazing. And of course, the quill was still popular in the late 18th century. A.J. Jacobs: Right. And in fact, as part of this, I went to visit the only place that still makes parchment, real parchment, which is made with animal skin, and that's what the Constitution was made on. So, their business now is partly for writing the Torah, writing scrolls. Russ Roberts: Yeah, it's a bizarre, fascinating thing to me that you're not allowed to use that any more advanced technology than the quill and the parchment for the writing of the Torah. But, as you point out, for fine documents, like the Constitution, that was the habit of 230 years ago. And, you of course visited the Constitution at the National Archives, the actual piece of parchment. And, it's under protective lighting, right? Russ Roberts: But, it's doing okay, right, on that parchment with the ink? A.J. Jacobs: Yeah, no, it has survived. It is remarkable. Going to the Archives was one of my favorite adventures because, like you say, it's like a cathedral. So, it's very dark and it's in this titanium case with argon gas. And, the good part--as you know, I like to see the pros and the cons of everything. So, the pro is that we still have this amazing document that did build America, and it does inspire people when they go see , and they think, 'Oh, I should be more involved in politics. I should learn civics.' So, that's the pro. The con--and this I got from several of my advisors--was that it sort of turns it into this sacred, static piece of parchment that is frozen in time, as opposed to the way the Founding Fathers viewed the Constitution as something--a process. And, it was about people; it wasn't just about the parchment. Russ Roberts: There is an argument it should be more like the Stanley Cup, which-- A.J. Jacobs: Passed around. Russ Roberts: Hockey players treat it like it's a beer goblet, a beer stein. You take it around, you show it to your friends, it goes on tour. You're right: we kind of hide the Constitution away as this precious artifact when it might be better to mingle with it: let it come down off Mount Sinai and mingle with the people a little bit more. A.J. Jacobs: Right. Well, one--I'm not sure we want to have it when people are too drunk on Madeira to treat it properly. But I do love the idea. And I also was fascinated with James Madison's view because the way we have it now is: You've got the Constitution, and then people append the Amendments at the end. They're like p.s., p.p.s., p.p.p.s. But, the way he wanted it to be was every time you amend the Constitution, you rewrite it. So, it was more like a Google Doc than what we have now. And, that, again, has pros and cons. One, it would show it's a more fluid document perhaps; but some argue having the horrible parts of the Constitution in there--the parts about enslaved people--reminds us how far we've come. So, like everything, it has its pros and cons. |

| 12:13 | Russ Roberts: Yeah, I want to talk about that. But, two quick things. At the end of your chapters, you have what you call 'Huzzahs,' which is a 18th-century word for 'Whoopee,' or you-go-girl, and 'Grievances,' which is a very constitutional word. Russ Roberts: Love that. A.J. Jacobs: And, by the way, I did learn that 'huzzah' was probably pronounced, 'huzzay,' but I'm going to stick with huzzah. But, yes, there were, as you say, there were pros and cons to living. So, on the one hand, you had the quill and the joy of thoughtful reflection away from the ding. On the other hand, I dressed the part. I mean, I put on my tricorn hat and my stockings; and I have never been more grateful for elastic. You take these things for granted. We've talked about taking things for granted before, but the fact that these stockings that I had that were authentic-style, they had no elastic, they would just slump to your ankles. You had to put on little tiny belts every morning. The amount of time I spent putting on sock belts was extraordinary. So, you do realize to be grateful for some of our advances. Russ Roberts: It's a good thing you got the pre-sharpened quills because when you take account of the time you had to put the belts on, the sharpening of the quill thing combined with that would have been really unproductive. |

| 13:43 | Russ Roberts: Before we continue, and I'll just tell my audience, A.J. is one of my favorite people to just banter with. We're going to have some banter, but there is some seriousness to this project. We'll talk about some of that, of course. But, talk for a minute about the research you did, because a lot of what makes this book delightful is it's full of anecdotes, facts, and the history of many things related to the Constitution and the Founding that I was unaware of. I'm sure you discovered those yourself in the course of writing the book. It wasn't like you were a Constitutional expert before you wrote the book. So, you mentioned your advisors in passing. Talk about that group and the books you read. Give us a little bit of pretentious intellectual background. A.J. Jacobs: Well, absolutely. I love the research. I love the living, I love the research. I love talking to you, bantering. I hate the writing. It's better with a quill. But, yes, I had a Board of Constitutional Advisors from all--law professors, scholars--but from all over, from the most liberal who said, 'Oh, the Constitution is just like a lump of Play-Doh, and we can make it whatever we want,' to others who were so originalist in their conception, they will not capitalize the phrase 'supreme court' because in the Constitution, it's a lowercase 's'. So, I had that. I read the books that they read. I read all sorts of history books, and I went on adventures to see the Constitution. But, yeah, it was fascinating to read all that I didn't know, but also stuff that they don't teach that much in history class. One of my favorite discoveries was reading the Notes--James Madison's Notes from the Constitutional Convention--because you realize how fluid things were. I just always figured, 'Oh, our form of government is--it's etched in stone--it's the way it's supposed to be. Two senators and one president.' But, no: You read and they were throwing out ideas that would seem crazy to us. And if not for a few votes the other way we might have, for instance, three presidents. When the delegate brought up the idea, it was--now, wait, I'm trying to remember which delegate. Wilson. Wilson brought up the idea of a single president. They all agreed there should be an executive branch, but it was not decided how that branch should be organized. He said, 'Let's have one president.' Other delegates said, 'What? Are you crazy? We just fought a bloody war to get rid of a king. Why do we want what they called the fetus of monarchy? This president will just take more and more power.' They wanted a poly-presidency--three presidents. Ben Franklin talked about twelve presidents at one point. And, they lost, 7-3, but it could have been the other way. And, that's what I love is: it jolts me out of my default mode that, 'Oh, this is the only way we can do something,' and realize how entrepreneurial and flexible-thinking these Founding Fathers were. And, that is--as I've said before, one of my favorite parts of you is that you change your mind. That you are a flexible thinker. And, I thought about that a ton while I was writing this book because--just to give you one anecdote--Ben Franklin said, in the Convention he said, 'The older I get, the less certain I am of my own opinions.' And, I feel that way, and that's one of the things that inspires me about you. Russ Roberts: Thank you, A.J. Appreciate that. Russ Roberts: As you mentioned a minute ago, there's some ugliness in the Constitution. And, it's fascinating to me, as it is to you, that--you said it's like a Google Doc--but they could have done it like a Google Doc where you don't track changes. Right? They could have had strikethroughs when they amended things. They could have left some of the uglier language and still wove in the Amendments. But they didn't. They put them at the end, and they left all the ugliness there. You, more than once, talk about the pros and cons of that, and especially when you write about Frederick Douglass. And, I think that part is quite moving--the idea that the Constitution with all its warts is a aspirational document. So, talk about that. A.J. Jacobs: Yeah, I love that phrase, 'aspirational document.' When I was researching Frederick Douglass, the great orator and thinker and former enslaved man from the 19th century--he represented one strain of how to interpret the Constitution. There was another--the other most famous abolitionist was William Lloyd Garrison. And he believed--the Constitution, he called it a pact with the devil. He said, 'It is evil because it does condone slavery.' And, he wanted to burn it. He literally is a showman. So, he would go and give these speeches and burn the Constitution. Originally, Frederick Douglass was on his side. But, sometime in the 1850s, Douglass took a different approach, which I love, which was: 'Let's not burn the Constitution, because there are good parts of the Constitution about liberty and the common welfare and freedom. So, let's view the Constitution as a promissory note--that it's a promissory note that we are trying to achieve a more perfect nation where everyone is free and everyone is equal; but we're not there yet, and we have to fight to try to make it more like the Constitution says.' And that language has resonated. Martin Luther King called the Constitution and the Declaration a promissory note. Obama gave a famous speech about race, which was basically the same idea: that we have to live up to the Constitution's greatest ideals. So, it's a lot about framing, as they say in cognitive behavioral therapy. It's: How do you see the Constitution? Do you see it for its best parts, or do you see it for its worst parts? |

| 20:40 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about freedom of speech. You're a big fan of it. I'm a big fan of it. It's under a little bit of attack these days, in both--in the cultural wars, not so much from the government, but a little bit from the government through regulation of technology and regulation of social media and so on. It's a little bit scary. I was surprised to hear about the early days of America and cursing-- A.J. Jacobs: I was shocked, too-- Russ Roberts: Talk to us about what that was about. A.J. Jacobs: I was shocked. As you say, I'm a big fan of freedom of speech, but I realized I'm more of a fan of the 20th and 21st century view of freedom of speech. A lot of our freedom of speech was expanded in the 1940s and 1950s, oddly due to lawsuits brought by the Jehovah's Witnesses. So, thank you Jehovah's Witnesses. But, the original 18th century version of free speech, which I don't want to return to, was much more constrained. There were, as you say, it was state laws--they weren't federal laws--but state laws against blasphemy and cursing. And, these were seen as Constitutional because their idea was that rights, like the freedom of speech, must be balanced with the common good. They had a much more balanced view of rights as not absolute or trump cards. And so, as part of my living Constitutionally, I did try to reinstate the New York State law from the 1790s, which was that you had to pay 37-and-a-half cents for every time you cursed or said 'damn.' And, I have teenage sons. I thought, 'This'll be good for them.' Of course, being smart teenagers, they figured out loopholes. They would say the s-word, and I would say, 'That's 37-and-a-half.' 'Oh, I don't have a half cent. Let's wait until I get to 75.' They'd get to 75, curse again, and be back to half cent. So, it wasn't hugely successful. But it was fascinating to see the evolution of the First Amendment. And, yeah: I don't have nostalgia for that original conception of First Amendment, which was much more constrained. |

| 23:03 | Russ Roberts: You talk about John Marshall's role in the Supreme Court as adjudicator of what's Constitutional. What's interesting, of course, is that: One, that wasn't built into the document--which is fascinating--the idea that the Supreme Court would be the determinant of Constitutionality. And, Two, I would add John Marshall's drinking rule. So, first, tell us why Marshall is important--Supreme Court Justice of the early 19th century. And, what preceded him? What did the Founders assume would determine Constitutionality? And then, tell us his drinking rule because I think that's [inaudible 00:23:46]. A.J. Jacobs: Absolutely. Well, what I found was fascinating is that, well, a lot of what we assume is in the Constitution is not. Including the Electoral College. You could split the votes, like Maine and Nebraska do now. It wasn't a winner-take-all for each state. And, one of them was the idea of the Supreme Court, which--and a lot of this is from a scholar at Stanford, Jonathan Gienapp, who is brilliant--but he talks about the Supreme Court was really third of three. It was the least powerful of the Branches. And, it was supposed to weigh in on what is Constitutional and what is not. But, it was not supposed to be the final and only say, which is what it is now. It was much more of a mix. The President would weigh in; Congress would weigh in. There was no idea that after Congress passed major legislation, people could file lawsuits with the Supreme Court to strike it down. And, it has grown in several ways. But, part of it is John Marshall, who was the third Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. And he famously staked out a lot more power for the Supreme Court and set up this idea of judicial review or judicial supremacy--which is what it really is--that the Supreme Court is the ultimate arbiter. And that is just not the way the Founders, many of them--it depends on--again, the Founders had a wide variety of opinions. So, Hamilton, for instance, was a Supreme Court fan. Jefferson hated the Supreme Court. But most of them would be shocked that we have these nine unelected people who have so much say over how we live our lives. It's undemocratic. It's unoriginalist. Now, again, people love[?loved?] John Marshall. So, he had his great parts, including that he--back then, in the early 1800s, the Supreme Court was kind of like a frat house. They all lived together and they all drank together. And they drank. I mean, there was a lot of day drinking in those times. And, he came up with a brilliant rule, which was, he said, 'We will only drink while deliberating if it's raining.' So, they would start deliberating, someone would open the window, 'Oh, it's not raining.' And, he would say, 'Our jurisdiction is so vast that it's probably raining somewhere in the United States. So, let's have some Madeira.' It's sort of the, 'It's five o'clock somewhere,' the origin of that. So, he was very good at loopholes and legalistic thinking. But I do think that the Supreme Court--the Founders did not get everything right, I think; but in this case, I do agree with them that the Supreme Court should not have this much power. |

| 26:53 | Russ Roberts: You point out there's a little clause in the Constitution that says, 'Congress has the power to grant letters of marque and reprisal.' I had no idea what those are. And, you not only found out and give us some of the history, but you actually petitioned for a letter of marque. And got it, I think. I think you did, right? A.J. Jacobs: It's still out there. I'm crossing my fingers. Anything you could do. Yeah. Russ Roberts: You requested one. A.J. Jacobs: I requested one for sure, in person. Russ Roberts: Okay. So, what is it? It's actually quite important. Didn't know anything about it. Do now. A.J. Jacobs: Yeah, it's fascinating. Well, one thing that really struck me about the Constitution is you have these parts that are still so relevant. The Preamble--the 'We the People,' and the 'Blessings of Liberty'--those are 52 of the most inspiring words I've ever read. But then, you'll get to parts that you're, like, 'What?' And, you'll realize this was written, oh, 230 years ago. And one of them is in Article I, Section 8: 'Congress has the power to grant a letter of marque and reprisal.' This is basically legalized piracy, government-sanctioned piracy. Because we, at the start, had very little--our navy was very meager, so we outsourced it. It was very libertarian, in a way. If you had a fishing boat or a merchant ship, you could apply to Congress, and they said, 'Okay, put some cannons on, put some muskets on it. And, you go out and you capture the British ships. And, if you capture them, you get to keep the booty. You get to keep the sherry, you can sell it to the government, you can sell it to private [?].' So, they captured guns and sherry and uniforms from the British. Two thousand boats were captured by these privateers, and we would not have won the Revolution without them. They're sort of unsung heroes of the Revolution--because they have a little taint, they have that piracy taint. But on the other hand, they were fighting for us. So, again, it's nuanced. Russ Roberts: So, talk about your own efforts to get a letter of marque, which is really kind of ridiculous, A.J., but I did enjoy it. A.J. Jacobs: Well, I figured it's still in the Constitution. It still says--there's no clause that says, 'No, you can't do it anymore.' So, as part of my project to live the Constitution originally, I said, 'I'm going to try, see if I can be the first person since 1815 to get a letter of marque from Congress.' I set up a meeting with a congressman from California, Ro Khanna. I met him with my tricorn hat at a hotel lobby, and I said, 'Congressman, I would like to apply for a letter of marque and reprisal. Here's my application--handwritten application--saying, why, what: that I would take my friend's water-skiing boat out on the high seas and try to fight for America.' What I loved is he was so enthusiastic. He said, 'What can we do to make this happen?' But, that was before he knew what a letter of marque was. And then I explained to him, and he was like, 'Oh. No, I've never heard of that.' And then, he became a little more cautious about granting me the right to go to the Taiwan Straits or whatever. But, he actually appreciated the premise of the book. So, he said he brought it up with his colleagues in Congress. It did not get a huge amount of traction. But, I've been in touch with him, and his legislative head calls me Captain Jacobs, so at least I've got that. Russ Roberts: Yeah, it's not bad. A.J. Jacobs: Yeah, something. Russ Roberts: It's one of many scenes in the book where I always wonder--I don't think you made any of them up, A.J. I don't want to accuse you of that. But I do wonder how normal people treated you like you were a serious person wearing a tricorn hat, requesting to turn a fishing boat into a warship, and various other adventures you're on in the course of the project. A.J. Jacobs: Yeah, definitely a mix of reactions. I mean, I commit--as my son says, I commit to the bit. It's like method acting for me: it's method writing. So, I really get into the mindset. So, when I go in with earnestness and curiosity, people do sometimes react and take me seriously. I will say: carrying a musket, because I had an original--that's how I did my Second Amendment--I had an actual musket from the 1700s that I carried around New York, that was mixed reaction. Some people not happy. They would cross the street. It did come in handy at least once. I arrived at my local coffee shop at the same time as another customer, and he said, 'You go first. I am not going to mess with you.' So, it did allow me to save a little time. But yeah, no: I feel it's almost like in service of the greater good of trying to figure out what the Constitution means, it's okay for me to be totally ridiculous sometimes. |

| 32:25 | Russ Roberts: So, I can relate to this for a couple of reasons. My dad had a streak like that. He wasn't writing a book. He would enjoy taking on a persona like that sometimes. I sing in parking garages often because I like the acoustics--in full voice. And, my children do not approve of that. And, part of it is--maybe a commentary on my voice--I tend to sing Robert Burns' "My Love Is Like a Red, Red Rose,"--not at the top of the charts these days. But, your children, and your wife--which is why I asked you about your marital status earlier in the conversation--they often were pulled along in this. And, did you struggle with them and their willingness to have you play the role? A.J. Jacobs: Oh, absolutely. I mean, it was--again, a mixed reaction. Sometimes they were so embarrassed they would not walk within one block of me. My oldest son actually got into it, and he put on the tricorn hat. So, that was exciting. Julie--I joined a Revolutionary War reenactment group, and Julie came along and put on the bonnet a couple of times. But there were parts that they hated. As I mentioned, I quartered a soldier. I provided quarters for a soldier, as is my Third Amendment right. She didn't love having this soldier in our house. It was only, like, three or four days of quartering. There was another part where I had to deal with gender and gender equality. And, some hardcore originalists say that sections like the 14th Amendment about equal protection under the law, that they do not apply to gender. Because when that amendment was written in the 1860s, those writers and ratifiers were not thinking about women--women's equality. So, there was famously many laws--state laws--that said women--married women in the 18th and 19th century--had fewer rights than single women, weirdly. And you could--for instance, a married woman could not sign a contract. So, I thought, 'Well, I'm trying to live this way. Let me see. Maybe I should take over all the contracts in our house.' My wife co-owns an event company, Watson Adventures, and she does tons of contracts every day. She is much more financially savvy and business savvy than me. But I said, 'Since we're doing this, let me just try to take over all the contracts.' So, she let me do it for about an hour until I was fired. I was such a disaster. And, she said, 'This is not working for me.' So, yes, I had a very brief attempt to follow 19th century marriage laws. Russ Roberts: Did you tell your sons that the royalties from this book could be decisive in their college education and they should play along more enthusiastically? A.J. Jacobs: Well, that is a good argument that I should have made. Back then, kids, they did all the chores. And so, I did try to institute that as well. That didn't go. I will say--this was a fascinating little chapter of my project--I talked to a scholar of constitutions around the world and he said there is a movement for families to write constitutions. Russ Roberts: Oh, yeah, I like that. A.J. Jacobs: So, that was wonderful. And, I said, 'Okay, I'm in.' So, I created a Family Constitution. Again, the delegates--my sons--were very hard to wrangle, to sit down and actually work it out. But, there are two parts that I like. One is I did a sort of a Preamble, which I feel is a mission statement for our family, which was basically that we should pursue our own happiness, but at the same time try to improve the happiness and well-being of others in our community and the world and even the universe. And then, the other part was, like the Constitution, there was a Bill of Rights. It's, like, you have the right to sleep in on Saturday and not be made fun of. But also, a Bill of Responsibilities. Because the mindset in the 18th century was very much about virtue, responsibilities, sacrificing for others, being a part of the community. And, they didn't have a bill of responsibilities written because it was just assumed. You would serve in the militia. That's what all adult males did. So, I don't want my kids serving in the militia; but we did create a Bill of Responsibilities to recapture a little of that idea of virtue from the 18th century. Granted, it was, back then, a very narrow virtue because the community that you were sacrificing for was very narrow--white men. But, still, the idea is thinking not just of yourself, but thinking of others. Russ Roberts: I read that part, of course, but I can't remember whether the Jacobs Family Constitution had two presidents or how you handled the executive branch. A.J. Jacobs: It doesn't yet. Russ Roberts: It's in there, I'm sure. A.J. Jacobs: Well, it's interesting. I mean, there are several parts to the real Constitution. There's the Preamble, which is sort of the mission statement. The Bill of Rights--those are the rights. But then, a lot of it is about the structure--the: how do we structure, how do we--these are the rules for making laws. Now, I felt that our family--like most modern families, my wife and I were sort of the tyrants. There was an imbalance; and I thought--and it can be tiring being the tyrant, making the decisions--'What if I could replicate the U.S. judicial system just a little?' So, I decided we would be the Supreme Court--my wife and I--but if two of our three kids had a dispute, first they had to go to the third kid. If they didn't like his decision, they could go to the appellate court level, which was their cousins who were in their 20s, and they could text them the problem and the cousins could weigh in. Didn't like that, they could go to the Supreme Court--to me and my wife. I still stand by it that it's an interesting idea to outsource a little bit of the--it was not hugely successful because, first of all, the lower court refused to hear--one of the sons was[?], 'I'm not wasting my time listening to your complaints.' And then, the middle court, they didn't like the decision. But, it was a fun attempt. It was all about experimentation, which is a very Founding Fathers way of looking at the world. |

| 39:45 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about voting; and food. A lovely part of the book is your cake project. So, talk about how you tried to vote publicly and how that was received by the polling workers; and then the cake and rum-punch story. A.J. Jacobs: Yeah, absolutely. Well, that, as you say, was one of my favorite--and it was a running theme through the book--is the idea of: voting in the 18th century, like everything, had its pros and cons. One con was, of course, it was restricted to white males. Another con was they didn't have the secret ballot. That was a much later import from Australia. You would vote by voice. Not every state, but most states, you would come to the voting booth and say, 'I would like to vote for candidate, for George Washington.' And, that was your vote. So, I actually tried to replicate that. I went to the voting booth in New York City, and I said to the woman at the door, 'I would like to vote for Kathy Hochul for Governor.' And, she said, 'Shh, shh,' like it was very taboo. She said, 'We don't do that.' I said, 'I'm trying to vote like my Founding Fathers.' She said, 'Well, we've moved on.' So, I had to vote the newer way with a secret ballot. But, that said, there were some parts that we don't want to go back to. But, there are other parts that I absolutely think that we should try to recapture. And one of them is that Election Day was festive, at least for those who could vote. There was farmer's markets, there was music, and there was rum punch, and there were cakes. Election cakes were a tradition. People would bake election cakes. They were made with figs and cloves--so maybe not your taste--but some of them were huge, 70 pounds. And they would come, because this was an amazing new right, this right to have a say in who governs you. And, they wanted to celebrate it. 'Democracy is sweet'--that's sort of the overly cute way of saying it. So, I was, like, 'Let's recapture that.' And I got--at first, I did it just myself, the first November of 2022, and I did bring cake and rum to the--and people got a little too into the rum, including an election worker. So, I decided I'm not going to do that again. But, the next year I brought it bigger, and I started a movement where I got someone in all 50 states to bake an election cake and bring it to the polls. And, it was the most touching part of the whole experiment for me, because people would write and they would say, 'I've been so depressed, I feel so unmotivated and disenfranchised, and this little positivity, this little action, even if it's just baking a cake, it reminds me that, yeah, this is an amazing thing, that we've got to keep our democracy and we've got to fight for it.' So, it was wonderful. I loved the--and I'm going to do it again. Russ Roberts: It's a beautiful idea. A.J. Jacobs: I'm trying in 2024. So, anyone who wants to bake, we are going to set up, we have photos; and please, just bake away and get in touch with me. Russ Roberts: And, you don't have to put cloves in it, right? A.J. Jacobs: That's true. I was sort of like: how the Constitution can evolve, the recipe can evolve. So, people were very creative, though. The Georgia people put peaches in their cake, and Michigan had cherries. Because I guess, I didn't know, Michigan is a big cherry state. So, yeah, it was a wonderful experience. |

| 43:46 | Russ Roberts: Now, I'm ashamed to admit that I am not very good at the Amendments. My knowledge kind of ends after the first two. And I usually defend that by saying they're the only two that people pay attention to-- A.J. Jacobs: Good point-- Russ Roberts: but, it's not exactly true. Recently at an event I made that claim, and someone said, 'Well, what about the 13th Amendment?' I'm thinking, 'Which one is that?' But, it turns out it's against slavery. And, I would argue that it eliminated slavery. But I don't think that amendment is actually necessary. I don't think we're at risk of returning. But, of course, we do observe it--very, very faithfully--and should. It's a good thing. But, there's 27 of them. And the 27th, I should have known about; I probably had heard about it. But, it's an extraordinary story-- A.J. Jacobs: I love this-- Russ Roberts: So, talk about the 27th Amendment. In preparing for this, I went back--I got online and I looked at the Constitution, online, and I looked at the 27 Amendments. And the Wikipedia page for the Amendments has which states--you should talk about it--how the amendments actually--what's required for them to pass. And then, it talked about how long it took for the process. And, it'll say: A year and seven days. Two years and three days. But the 27th Amendment took over 200 years to pass. That's astounding and extraordinary. So, talk about--for ignoramuses like myself--how does an amendment get passed? In practice? There's different ways, but in practice it's mainly one way. And, what was the 27th Amendment about and why did it take 200 years? And, how did it still manage to pass? A.J. Jacobs: Yeah, it's an amazing story, one of my favorites. And, it's very hard to pass an amendment to the Constitution. Harder than the Founding Fathers thought because they didn't foresee this two-party system quite as entrenched as it is. So, there have been thousands of proposals and only 27--and 27th is the last one to pass, and it was 1992. And, it is in a large part because of one man. I mean, it made me realize, sometimes one person can change history. It was a Texas college student named Gregory Watson, and he was doing his paper for his government course, and he discovered James Madison had written 12 amendments, and two of them did not pass. The 10 that passed are what we know as the Bill of Rights. One of those 12 was that Congress should not be able to give itself a raise in that same quarter. They can raise their salary for the next session. And, he said, 'Well, this seems like a good idea.' His teacher gave him a bad grade. So, he's like, 'I'm going to show that teacher.' And he went on a campaign, a letter-writing campaign, because it turned out this amendment had never been rejected. It just never got enough states. He needed three quarters of the states to pass it, and they were two shy, I believe. So, it's sort of a zombie amendment: it's still hanging in there. And he said, 'If I can get three quarters of the current United States, then this amendment will actually be ratified.' So, he wrote state legislators and said, 'This is a good amendment. It makes sense. Congress should not be allowed to give itself,--' He got--Maine was the first state to say: Okay. And, after that, the dominoes fell. And in 1992, it was ratified because of the efforts of this one man. And, I just love that. It was a very American story to me, that one man can do it. But, I talked to him--I interviewed him. And he said he's very worried because when is there going to be a 28th Amendment? We are so divided. We are so divided that it's going to be so hard to pass another amendment. Which is a problem, because the Founders knew this was an imperfect document. They wanted it to be amended. George Washington wrote his nephew, a couple of weeks after the Convention, said, 'It's an imperfect document. It's up to the next generations to improve it.' But, it's very hard. It's very hard right now. One of the hardest in the world to amend. Russ Roberts: However, the Supreme Court manages to amend it de facto, if not de jure. So, the way they interpret things, because it's hard to amend explicitly, they've found a way to amend it implicitly, I would suggest. A.J. Jacobs: Absolutely. And that is--that is the way--if you can't amend it, then you can change the way you interpret it. And, as I talk about in the book, that has its pros and cons. You've got the two sides. You've got the originalists, which is usually associated with conservatives, and there are originalist justices on the Supreme Court like Clarence Thomas and Alito, and they believe we should focus on the original meaning of the Constitution when it was ratified. Then there's the other side, the living Constitutionalists or pragmatists, or pluralists, they're sometimes called, who believe that you should take the original meaning into account; but, since times have changed and technology has changed, you also have to evolve the meaning. So, for instance, the 14th Amendment, if you're a true originalist, those ratifiers did not think about it applying to gay marriage. Therefore, the 14th Amendment says nothing about gay marriage. A living constitutionalist would say, 'Yeah, well, they didn't think about that, but that's what equality means now. So, the 14th Amendment does apply to gay marriage.' And, I tend to--I guess one metaphor when I think of the Constitution is I do feel there should be some elasticity. So, it's like a pair of pants. You want an elastic pair. You don't want it so loose that there's no structure. You do want the basics, like freedom of speech and equal protection. But at the same time, you don't want it like a pair of skinny jeans that it's so rigid that you gain two pounds and it splits open. So, it's all about how much elasticity should it have while still maintaining a structure so that we can continue to live and predict what the laws are going to be. Russ Roberts: If you've ever been in the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., which is very inspiring and beautiful, I was struck by the fact that it was, I think, constructed during the Roosevelt Administration--FDR's [Franklin Delano Roosevelt's]--and the quote they chose for the rotunda is a very much living-Constitution quote, because Roosevelt was very eager to expand the powers of both the Legislature and the President. But then, of course, go a few feet away, a few hundred meters or so, there's the Roosevelt Memorial--FDR's memorial--that was built long after Roosevelt had died. And so, turnabout is fair play: He's not shown smoking anywhere in that memorial because that's taboo in modern times. But, Roosevelt was a proud smoker. Roosevelt is in a wheelchair. He was, in fact, in his day, never seen in a wheelchair. He was very careful to make sure that people did not know that he was in a wheelchair. And in fact, my favorite revisionism and non-originalism for Roosevelt is that here is a man who was desperately trying to get America into World War II, and one of the biggest quotes is about his pacifism and his hatred of war. Now, nobody likes war, but you wouldn't exactly call Franklin Delano Roosevelt a pacifist. But, that's the way it goes sometimes. You embrace the flexibilities; sometimes you get some things that are not what you want. A.J. Jacobs: That is fascinating. Yeah, just a couple of comments. One was, yeah, Thomas Jefferson wanted a new constitution every 19 years. He was one of the more radical ones. And, also, yeah, I talk about FDR because I don't think I'm ready to go to three presidents, like we discussed, but I do feel that the president has gotten way too powerful. And, a lot of the jumps in power were during presidencies I admire, like Lincoln and FDR. But right now, the Presidency, it's what Arthur Schlesinger called The Imperial Presidency in the 1970s. The President has way too much power over war, over trade; and I would like to see--the Founding Fathers, I think would be shocked if they saw how powerful the President was. Congress was first among equals back then. So, I think they would want to go back to having Congress have more power. |

| 53:39 | Russ Roberts: Well, let's close with a couple of things about George Washington. And of course, those of us who have seen Hamilton-- my favorite scene in Hamilton is when George Washington tells Hamilton he is going to resign. He's not going to run again. It's not that he's going to resign: he's not going to run for a third term. And, a gorgeous song, "We'll Teach Them How to Say Goodbye": that Washington is going to go back to sit under his fig tree and have some tranquility. But you reveal in the book--which fascinated me--that there was a big argument about what the Executive Branch Head--we now call them the President--what their title was going to be. And, tell us some of the choices that were on the table. And, I have a story because this is a setup for me. You're just playing my straight man here, A.J. Go ahead. A.J. Jacobs: Well, yes, I was fascinated that there was a big struggle of what to call the President. Because, they respected Washington, sometimes revered him, but also they were so afraid of monarchy. Some people in the early government wanted to go more royal. They would[?] call him His Excellency or His Highness. One proposal, which was interesting, was that it should just be Washington. 'Washington' itself should be the title of the president, sort of how 'Czar' is based on Caesar. So there would be a Washington Obama, a Washington Trump; that would be the title. In the end, it was Washington himself who really struck down people like John Adams and said, 'No, just call me President.' And, I grew to admire Washington, who of course had huge moral flaws, but he also was amazing in his restraint--in his restraint--and said, 'I don't want to become a dictator or a king.' And, he stepped down. And he also said, 'Just call me President.' So, yeah, I am grateful that we have a President and not a His Highness Joe Biden. Russ Roberts: He was an extraordinary man. And that revulsion, I hope, at being worshiped, was part of his greatness. But, as you say, a lot of people, while they were happy to not to have the British monarchy, there's something in the human soul that sometimes longs to be ruled. Which is weird, because we also like autonomy, a great deal and freedom. And I'll just throw in a little Adam Smith here: In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, he talks a lot about how much we worship great political leaders, and we have that in our blood. And he has many interesting things to say about that. We'll link to a passage related to it. But the story I wanted to tell is that--because it was amazing when I read this about Washington being the generic title of the president, could have been. When Mayor Daley died, he had been mayor of Chicago forever, and they interviewed--his successor was Michael Bilandic. And on the news--I was living in Chicago at the time--there was an interview of a young girl, I think she was maybe 10 or 11, and she said, 'Yeah, the new mayor is Mayor Daley Bilandic.' Because in her mind, 'Mayor Daley' was the generic term for who was in charge of the city. And, it was the same idea. Which was creepy and weird and funny. A.J. Jacobs: That is hilarious. And yet, I mean, like you say, we sort of have this drive to have powerful leaders. And, they were very wary of the monarchy. So, they changed the English language in America. So things like King's College became Columbia College. King Street became Congress Street. King's Minuet became Congress Minuet. And I feel there's been a little backsliding. Now a lot of society seems obsessed with monarchy again, whether it's the British monarchy or just even a thing like Burger King and king-sized mattresses. So, yeah, I'm for democratizing: president-sized mattresses or senator-sized mattresses. I don't know if that's going to catch on. Russ Roberts: It's interesting, I think--never thought about it--I think moderns, who really don't want a king, I don't think-- Russ Roberts: but, we do like pomp. It's a funny word. I've never thought about it much other than using it in the title of the song for graduation, "Pomp and Circumstance"--the grandeur of the British monarchy in 2024, and shows like The Crown, which talk about, which deal with the fact that people do like certain aspects of the monarchy even when it's not anything like the kingdom that it was long ago in England. The amount that people like the robes and the jewels and the goofy hats and the stone [?Scottish Stone of Scone?--Econlib Ed.]--which I think is from Jerusalem--that when--what do you do with a king? You don't inaugurate him. What do you do, anoint him? You do something else. A.J. Jacobs: Yeah, the King's Coronation. Russ Roberts: You coronate the king. Thank you. And, the King's coronation, they take oil and they put it on this, I think--I don't know all the details because I'm not into pomp. I'm kind of an anti-pomp guy. I feel weird wearing garb, the garb of academic robes, and hats, and so on. At least until recently. Now that I'm the President of a college, I have to confess I'm a little more into it than I used to be. I'm ashamed of it, but it's a fact. A.J. Jacobs: It's good to be the king, sure. Russ Roberts: I don't want to hide that from my listeners. Anyway: Pomp is a weird thing, right? And, America is a relatively pomp-free leadership. But, you talk about when you visit Congress or the National Archives where the Constitution--there's some grandeur to it that I think taps into that human longing. A.J. Jacobs: Right. Well, a couple of things occurred. One is: I am not opposed to some pomp, because it's sort of rituals. And, I think humans are drawn, like you've had on the show, talked about many times. I think that it would be nice if there was a division of labor, which they have in many nations, where you've got the person who actually does the governing, and then you've got maybe an elected--not a king--but an elected pomp person who does all of the fancy parties. And I do think one area where there's more pomp than necessary is the Supreme Court, where they still wear the black robes. They're in this huge Supreme Court building, which is not the way the Founders envisioned it. The original Supreme Court, the very first one, was, like, in a building near a market, and they had to clear the butchers out because they were making too much noise. But, yes: So I think I would tone down the pomp in the Supreme Court and also create a Division of Pomp that would--so it's more efficient for the people actually governing. Russ Roberts: We need a CPO, a Chief Pomp Officer. A.J. Jacobs: I love that idea. |

| 1:01:50 | Russ Roberts: I'm trying to think, is there any--we have a carriage, I guess, on Inauguration Day on January 20th where they--I think it's a horse-drawn carriage, right? Or am I confusing that with the coronation or maybe the funeral of a British monarch? I'm totally in trouble here. A.J. Jacobs: I can't remember. Russ Roberts: Got anything for me? A.J. Jacobs: No. Well, I do remember that the last time the Constitution was moved, which was in the 1950s--it went from the Library of Congress to National Archives--that was like a pomp. They had a parade. It was a mile trek. But they put it on a beautiful mattress, a pillow, and it was in a tank. And, no, I guess it was in an armored car, but it had treads, it had soldiers with guns and horses and military bands, all to bring the Constitution. I mean, it is The Constitution. It was The Constitution. But that, I thought that was an interesting example of pomp. I can't remember what we do for the actual President, whether it's-- Russ Roberts: The fact is--people love to say that JFK [John F. Kennedy] was the first President who didn't wear a hat and that changed America. People stopped wearing hats. That is literally not true. Russ Roberts: He actually did wear a hat at his inauguration. There are two parts of it. At one point, he did wear a hat. I don't think that was the reason people stopped wearing hats. They had stopped wearing hats long before. But, the closest thing we have to pomp, really, is the swearing-in and the Oath of Office. Administered, of course, by the Chief Justice. Right? I think. A.J. Jacobs: Right. Yes, yes. And, as I say, rituals are important. As long as we don't deify the politicians, I think that it is fine to have rituals because they provide continuity and a little bit of respect--which, we do need some respect for institutions. But, yeah, we do have, as humans, this disturbing yearning for monarchy. And, I hope we can get over that. Russ Roberts: Yeah, that'd be good. |

| 1:04:09 | Russ Roberts: I was going to close with another George Washington thing, but I forgot; I want you to mention, because it's very relevant for our shared interest in epistemological humility, Ben Franklin's parable about the French lady, which he told at the Convention. Russ Roberts: At the Constitutional Convention. A.J. Jacobs: I love this because that's when I thought of you the most, was the epistemic humility of the Founding Fathers. And, I'll tell you that one, but just quickly, Madison, James Madison's last words, according to legend, were that he had changed his mind. He was on his deathbed. He made a face. His niece said, 'What's wrong?' He said, 'Oh, I just changed my mind.' We'll never know what he changed. It could have been about the bicameral legislature. It could have been about soup. Who knows? But, the fact is he changed his mind; and they were fine with changing their mind. And that is something that I love about you, and I want to get back to. And, Ben Franklin told a great story, a little joke at the Convention, where he said: There was this French lady who said to her sister, 'It's so strange. I have never met anyone in my life except for me--except for myself--who is right on every occasion.' And his point was, 'We're all that French lady.' We all think we're right on every occasion. But, it's not true. I mean, what are the chances that me, one of 8 billion people on the earth, has the correct take on every subject? It is probably two-to-one, maybe three-to-one odds. But it is, yeah, a little more than that. Yeah, so I love the idea of epistemic humility and flexible thinking, and that is an inspiration from the Founding Fathers. Russ Roberts: So, let's close with another George Washington story, which is the back of his chair. So, describe what the back of his chair looked like. And, it's a really beautiful metaphor for how you think about America and its future. And, I know you are an optimistic person. I used to be. I'm less optimistic than I once was. A.J. Jacobs: Understandable. Russ Roberts: Kind of changed my mind, I'm sorry to say. I remain optimistic on many things on a personal level, but nationally I'm less optimistic. But, tell us the George Washington chair story. A.J. Jacobs: Right. Well, I love this story because it was at the Constitutional Convention. George Washington was sitting in this big wooden chair, and carved into the chair was a carving of the sun. But it was only half the sun. It was the top half; you couldn't see the bottom. And, Ben Franklin looked at it through the long, hot months and he always wondered, 'Is it a rising sun or a setting sun?' Because he couldn't tell. And then, at the end of the Convention, when against all odds, they had created this document that people agreed on, he said, 'Now I realize it's a rising sun. The sun is rising on America.' And so, part of my quest in this project, this book, was to figure out, is the sun still rising in America or is it setting? And, one of my takeaways was: It's up to us. I mean, it's not like the sun. The sun, natural law is it's going to set. But we are the ones who can make the sun of democracy rise or set. We are the ones who have to get in there and roll up our sleeves and change gerrymandering and all sorts of other things, and bake election cakes, of course. And, that it's up to us whether the sun still rises on America. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been A.J. Jacobs. His book is The Year of Living Constitutionally. A.J., thanks for being part of EconTalk. A.J. Jacobs: Thank you, Russ. It was my pleasure. Huzzah. I should end with huzzah. Huzzay. |

What does it mean to live Constitutionally in the year 2024? For a start, it means getting off social media. It also means swapping a quill pen for your keyboard, and candlelight for electricity. And don't forget the tricorn hat and musket--though maybe skip the boiled mutton. Join author A.J. Jacobs as he deep-dives with EconTalk's Russ Roberts into the centuries-old principles of the U.S. Constitution and tries to apply them to the current day. Topics include the original conceptions of our most cherished amendments, the office of the President, and the supreme court, and an explanation of how one can be an originalist and still believe in gender equity. Jacobs also shares his family's experience writing its own constitution, and explains why his research made him more optimistic about the future of American democracy.

What does it mean to live Constitutionally in the year 2024? For a start, it means getting off social media. It also means swapping a quill pen for your keyboard, and candlelight for electricity. And don't forget the tricorn hat and musket--though maybe skip the boiled mutton. Join author A.J. Jacobs as he deep-dives with EconTalk's Russ Roberts into the centuries-old principles of the U.S. Constitution and tries to apply them to the current day. Topics include the original conceptions of our most cherished amendments, the office of the President, and the supreme court, and an explanation of how one can be an originalist and still believe in gender equity. Jacobs also shares his family's experience writing its own constitution, and explains why his research made him more optimistic about the future of American democracy.

READER COMMENTS

David Fountain

May 6 2024 at 12:27pm

Instantly one of my favourite episodes. I have been listening to Russ Roberts for years. He reached my brain through my ears with this one.

Amy Mossoff

May 6 2024 at 5:03pm

This might be my all-time favorite episode of EconTalk! Charming. I smiled through the whole thing. AJ’s project (and his personality!) is quintessentially American – quirky, irreverent, and somehow still serious and aspirational. I’m falling in love with America all over again. What a beautiful conversation.

I’m buying the book today, and then brushing up on cake recipes. Thank you, Russ Roberts, for another gem.

P.S. Can I nominate my 12-year-old daughter for CPO? What’s the process for that?

Matt

May 6 2024 at 7:29pm

Funny (and a nice switch from all the doom), but it would probably be more instructive to live as Elie Mystal would have lived back then. To quote his “Allow Me to Retort”:

“Our Constitution is not good. It is a document designed to create a society of enduring white male dominance, hastily edited in the margins to allow for what basic political rights white men could be convinced to share. Conservatives are out here acting like the Constitution was etched by divine flame upon stone tablets, when in reality it was scrawled out over a sweaty summer by people making deals with actual monsters who were trying to protect their rights to rape the humans they held in bondage.”

Mark

May 6 2024 at 8:26pm

On state laws against blasphemy: Not a con law expert, so feel free to correct me here. My understanding of the bill of rights was that it was originally directed solely against the federal government. It wasn’t until ratification of the 14th amendment that these rights were incorporated against state governments as well. This is partly why we see so many state constitutions ‘repeating’ language in the bill of rights, and why you might see what we would today consider a clearly ‘unconstitutional’ law abridging the freedom of speech in a state constitution.

Indeed, I’m not sure the states would have originally ratified a document that included so many restrictions against their own power.

Shalom Freedman

May 9 2024 at 7:29am

The interesting element in this conversation for me is the surprising information Jacobs provide about the Constitution and its makers. Who ever knew that there was consideration of a multi-person leadership? of Jefferson’s opposition to Marshall’s giving the Supreme Court additional powers? I am sure Jacobs’ book is rich in all kinds of information like this.

On the other hand, the gimmick of the project Jacobs seemingly living like one of the founding fathers seems to me just silly though silliness is not I suppose the worst thing in the world.

Earl Rodd

May 9 2024 at 12:00pm

Interesting discussion. A couple comments.

There is an interesting example of the idea of having a “ceremonial president.” While constitutional monarchies all have this feature to an extent, Australia does it without an in-country monarch. If you read the Australian constitution, you see a strong executive branch. What has evolved in practice is very different. The executive is the Governor General. While on paper he has a lot of power, and has exercised it (in one of the most contentious episodes in Australian history in the 1970s). Mostly he lives in a lovely house and attends fancy dinners and function. The arrangement seems to work well, although the prime minister still does his share of official social functions.

Note: The Governor General is appointed by the British king or queen, though in practice, the Aussie prime minister tells the monarch who to appoint.

Earl Rodd

May 9 2024 at 2:51pm

I loved the idea of working to recreate election day as a festive time celebrating all that is meant by our right to vote. I was a poll workers for some years until recently. For we poll workers, it was a festive time of sorts. Yes, it was hard work(*) and a long (5AM – 9PM or later) day, but we got to know each other and enjoyed each other’s company . Sometimes the greatest part was a whole day of never talking politics (we were prohibited from doing so while working the polls). We shared lunch and dinner treats and working together. We greeted people we knew. But sadly, this, and the ability to make election day a special day, fell apart when universal mail-in voting hit. Poll working was so discouraging – we did all the setup work for a full complement of voters yet half of them had voted by mail or early. I quit the job – it seems like a waste of money and effort to put on an in-person election with all its controls when election integrity has already taken the integrity compromise that comes with mail-in voting.

(*) The new Dominion Voting Machines we have include a pretty good user interface, excellent end-of-day software but terrible! mechanics. They are obviously designed from cheap off-the-shelf parts that don’t work well together creating multiple problems that make them difficult and slow to setup. The mechanical design leaves open multiple key components that should be secure requiring extra work putting various kinds of seals over parts of the machines.

Jeanne Groves

May 12 2024 at 6:36pm

The comment about not knowing the various amendments had me searching for the delightful “Born Yesterday” film (later version with Melanie Griffith) and the constitution song. A wonderful way to learn the first 19 amendments.

Trent

May 12 2024 at 8:26pm

During the discussion about how there seems to be something within humans desiring to be ruled by somebody, I couldn’t help but think of ancient Israel, and how the Israelites wanted their own king because all the other nations at the time had kings. After warning the Israelites that it might not work out so well as they imagined, God gave them what they wanted. After only four kings (Saul, David, Solomon, Rehoboam), Israel was divided, and that was the end of a single monarchy ruling over a unified Israel.

On an entirely different note, I’m wondering how my wife would react if I decided to switch to writing with a sharpened quill and ink bowl…especially when signing the bill at restaurants.

Great episode!