Megan McArdle, Washington Post columnist and previous EconTalk guest, joined host Russ Roberts in this episode to discuss the “dazzling hindsight” with which we view recent crises. Why can’t we seem to get it right in crises like the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent Texas energy crisis? And why don’t we seem to learn from our mistakes? “When an unlikely thing hasn’t happened for a while, we think it’s never going to happen again. And, when an unlikely thing just happened, we think we need to take a lot of preparation against it,” says McArdle.

As a journalist, McArdle has had a unique opportunity to revisit her own predictions (and nasty reviews!), an opportunity she’s taken advantage of. In this conversation, she shares some of what she’s learned, and now we’d like to hear your thoughts. Answer our questions below in the comments, or use them to start an all new conversation offline. We love to hear from you, and we’ll always be here for the conversation.

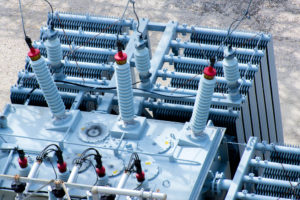

1- Roberts and McArdle discuss the recent winter storm in Texas that left millions without power. How much insurance should we have for events like this? (You might want to think about insuring for prevention versus adaptability.) McArdle also argues that Americans have zero political taste for these sorts of expenditures, so how can this distaste be accommodated?

2- The conversation turns to our experience of the COVID pandemic. To what extent is the pandemic a black swan event? Why does McArdle draw a distinction between stockpiling supplies and stockpiling capacities? To what extent do you think we’ll be better prepared for another such event in the future, and why?

3- What were some of the missteps and lost opportunities of the Trump administration in response to COVID, according to McArdle? What would she have done differently to leverage “a huge benefit of soft power.” How well do you think her suggestions would have worked, and why?

4- How have the costs of the COVID pandemic been felt differentially by income- for example, the costs of school closures. Roberts asks, “who plans, who takes the risk, who builds the insurance, the capacity for adaptation?” How would you answer this question? Can such planning mitigate these income effects ?

5- McArdle is critical of the politicization of public health. What does she mean when she says we would we have been better prepared for this pandemic in 1930? Is she right??? Explain.

READER COMMENTS

John Alcorn

Apr 6 2021 at 6:12pm

Amy,

Some thoughts:

1. Russ Roberts pointed out: “there’s too many things to worry about. And it’s not a cognitive problem. It’s that preparing for the array of existential risks would require a fundamental readjustment of life that most people literally don’t want. And, they’re much happier adapting, doing the best they can.”

2. a & b) In recent years, regional outbreaks of new infectious diseases prompted many experts to advocate investment in capacity/readiness for (random, stratified) surveillance testing. Nations that recently had experienced a fright were better prepared for SARS-CoV-2. c) The crucible of the COVID-19 pandemic leaves the USA better prepared for a similar pandemic. Will readiness decay, if perchance many years pass without a major pandemic challenge?

3. Sharp polarization about President Trump became more acute in an election year (witness impeachment efforts as SARS-Cov-2 emerged). My intuition is that ‘effective messaging’ was not in the cards. Style (sender) and polarization (receivers) made policy discourse a tragedy and drama of stylized presentation of self, alter-casting, and outcasting.

I would note that COVID-19 cumulative death rates in the USA and in the European Union are roughly the same. These polities are large, sprawling, populous, modern federations of States/Nations, with decentralized pandemic control policies. The pandemic works its way through, as people and policies adapt to ups and downs in perceived risk, in what Tyler Cowen calls the epidemic yoyo.

4. a) The pandemic exacerbated inequality. Zoom workers vs essential workers. Belmont vs Fishtown. Big Tech = winners. Homeowners = winners. b) I linked (at this EconTalk episode) to Ian Martin’s and Robert Pindyck’s framework, re: risk-analysis and ‘willingness to pay’ to avert catastrophes. BTW, Prof. Pindyck was a guest at EconTalk a few years ago, re: climate change.

5. Mission creep, bureaucracy, strategic blame avoidance, lack of accountability, and what Italians call ‘protagonism’ (desire to be in the limelight) beset public health agencies. Thank goodness Casey Mulligan, Alex Tabarrok, and some other determined top economists made a difference, helping to hasten vaccine development and other smart initiatives in public health during the pandemic.

Amy Willis

Apr 14 2021 at 1:29pm

@John, I love (sadly) your answer to #4 especially. This has been a concern I’ve been raising from near Day One. My family and I, for example, were relatively little affected. My livelihood was never in danger, my kiddo stayed in school (mostly). And I’m kind of an introvert to boot. The biggest losses to me were luxury goods. Related, the biggest “silver lining” I see is the possible upset to the structure of public schooling. I believe there are unintended consequences in that sector that will be generational.

John Alcorn

Apr 6 2021 at 6:20pm

PS: Robin Hanson has sketched pandemic insurance institutions/markets (link here).

Roger McKinney

Apr 7 2021 at 3:06pm

There is a lot of misinformation about the Texas ice/electricity disaster. Here’s a few:

Texas is connected to the national grid, but by DC power. Most electricity is AC, so anyone selling to TX has to convert to DC. The main advantage to DC power is that it travels farther with less loss than AC.

TX couldn’t get electricity from surrounding states because they had the same problems as TX. OK lost 30% of its power for the same reasons as TX. KS, MO, AR, TN, NM and many other states suffered the exact same problems as TX but never made the news. The media fixated on TX because it’s politically conservative and they wanted to trash it.

The cold wasn’t unique. It matched records set in the early 20th century. That means industrialization didn’t cause it.

Federal regulations had forced TX to shut down all of its coal fired plants leaving it dependent on natgas and wind. Coal fired plants in other states with worse cold suffered few problems. TX needed more diversity in fuel for electrical generation.

TX never deregulated its electrical industry. It merely separated generation from transmission, making it like cable TV. Generators could compete on price, but they still suffered glaciers of regulations.

Wind power was only about 20% of TX power and most of it didn’t fail. The biggest problem was freezing of natgas processing facilities.

Amy Willis

Apr 14 2021 at 1:27pm

@Roger, SO MUCH conflicting info. FYI- we will have some pieces specifically on the Texas energy crisis coming soon… Stay tuned!

Comments are closed.