Space Age Utopianism

By Kevin Lavery

Zach Weinersmith joins EconTalk host Russ Roberts for the third time to discuss why ambitions of space exploration are unrealistic and overly optimistic, the danger of all-encompassing utopianism, and why space settlement is not like buying a hot tub.

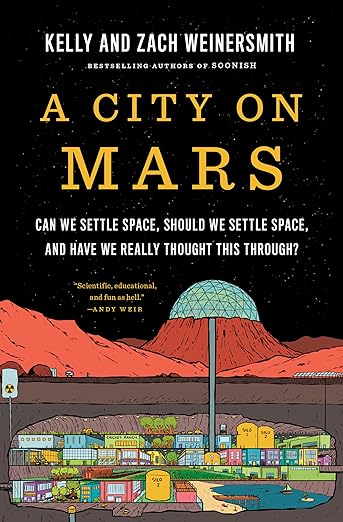

Weinersmith is a cartoonist and author/co-author of many books, including Bea Wolf, Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That’ll Improve and/or Ruin Everything, and the topic of this podcast episode, A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? Weinersmith is also the author of Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, a daily comic strip.

The podcast revolves around understanding space settlement as an ambition with roadblocks. Weinersmith shuts down the possibility of a settlement on the moon, for example, due to its lack of water, difficulty of extracting resources, and lack of an atmosphere. He says even though Mars is far more promising, it carries its own drawbacks: It is six months travel away from Earth and has planetary-wide dust storms. In general, humans don’t have the technological ability for long-term space settlement. Despite this, Weinersmith sees the literature on space settlement as biased towards advocacy for space exploration, regardless of the resource constraints and trade-offs.

Negative trade-offs have always impacted space missions. Weinersmith’s example is the Apollo program, which he regards as politically unpopular, feasible only once, and far too costly in terms of resources only to briefly go to the moon. But the most concerning drawback comes with the question of whether space settlement is ethical given the negative effects of space on human biology, psychology, and development.

Weinersmith outlines how the political showmanship common in space exploration projects, as opposed to earnest scientific curiosity, means we know almost nothing about how space affects pregnant people and newborn children. This would make any future children born in space lab rats. To Weinersmith, all these problems make it incredibly difficult and unethical, for very little upside, prompting the response from Roberts, “What’s the appeal of this?”

Roberts asks Weinersmith if it worries him that his claim of the nearly impossible difficulty of space settlement is overlooking technological innovation. After all, there are many existing technologies that were once seen as impossible, like the airplane. Weinersmith dismisses this argument, as it’s more of a hope than a legitimate retort, and the necessity of remarkable innovation points more to space settlement’s infeasibility.

As Space X has shown, space travel can be privatized. Should the lack of technology for settlement prevent companies from attempting missions into space? Weinersmith calls this the hot tub argument, as space travel can be as private as the decision of buying a hot tub. But Weinersmith disagrees. He believes that space travel presents a risk to humankind, large enough to the point where some veto power should be given to third parties.

Though most of the podcast is spent discussing why a city on Mars or the Moon is a fantasy which hasn’t been thought through, Weinersmith acknowledges that the will to expand human civilization into space is an understandable application of the explorer mindset of humans. He lauds the questions prompted by space advocates as fascinating and intriguing. Weinersmith is not telling his audience to stop exploring, innovating, or asking questions. Instead, he is calling for the utopianism surrounding space exploration to slow down, an acknowledgement of the tall barriers and severe risk.

Quite consistently throughout the episode, Roberts says Weinersmith’s ideas are somewhat discouraging. But I don’t think so. Weinersmith’s work acknowledges that there are no panaceas, and the attempt to create one can have disastrous consequences. Given the occasionally depressing state of the world, it is appealing to be able to start anew. Weinersmith is asking the audience to examine the costs of doing that. In my opinion, those costs begin with climate change. Space exploration is a tactic of avoidance, not a genuine solution, as is often the case with utopian ambitions. For instance, socialism is not a solution to economic inequality, social alienation, or worker maltreatment; it is a hypothetical rocket-ship to a world where the faults of capitalism don’t exist, without regard for the ethical or economic constraints of the new system. Utopianism has a high opportunity cost, namely a counter-intuitive diversion of attention away from contemporary problems. The resources which could be devoted to the innovation necessary for planetary settlement over an undetermined length of time could instead be devoted to reducing carbon emissions and expanding green energy. Utopianism isn’t feasible, but it also isn’t preferable.

Related EconTalk Episodes

Zach Weinersmith on Beowulf and Bea Wolf

Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith on Soonish