Did you know that nearly EIGHTY PERCENT of Americans will experience at least one year of living at or below the poverty level? On the flip side, almost 40% of Americans will also spend at least one year in the top 10% of income earners. So what is poverty? According to sociologist and author Mark Rank, poverty is not an “us” or “them” phenomenon, as it affects us all-both economically and morally. In this episode, EconTalk host Russ Roberts welcomes Rank to explore these questions and more.

Now it’s your turn to help us continue our conversation. If you have relevant experiences to share, we’d be honored to hear them. We’re also interested in your responses to the questions below. Share your reflections on this episode in the comments, at your dinner table, or drop us a note at econlib@libertyfund.org. We love to hear from you.

1- How is poverty measured, and how has the process changed over time? We know Russ to be skeptical of such measurements; what does he suggest this particular calculation misses?

2- Rank points to Amartya Sen‘s definition of poverty as a lack of freedom. What does this mean? To what extent do you find this to be a useful definition?

3- What does Rank mean when he invokes the “us versus them distinction” with regard to poverty? How does the notion of the “lifetime risk” of poverty disprove the myth that most people who are poor will always be poor? How does the distinction of income versus assets affect the way we measure poverty? Since a majority of people in America will experience poverty at some point, how should this change the way we think about it?

4- Related to the question above, there are still people who are persistently poor- about 10-15% of those living in poverty constitute an “underclass” of poor households. How is this sort of poverty different from others, according to Rank? In discussing childhood poverty in particular, what does Rank mean when he says we’re paying on the back rather than the front end of the problem?

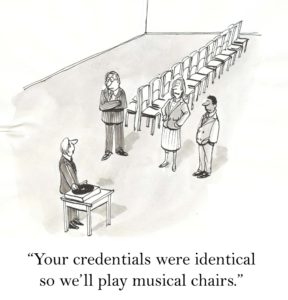

5- Rank argues that in order to mitigate the effects of poverty in America – and especially the problem of the persistently poor- we need structural changes more than transfer payments. (Think of his two analogies- musical chairs and queuing.) What are some of the policy suggestions he offers, and what is your assessment of each? What additional proposals might you offer?

READER COMMENTS

Garrett

May 10 2021 at 2:03pm

If you’re using income to define “living at or below the poverty level” then that’s not surprising since I’m sure there are lots of college grads who take a little while to get a well-paying job and live with their parents until then, but I wouldn’t call that poverty since they have a safety net. If you aren’t using income, then it seems apples-to-oranges to compare that to then compare that top income earners, especially if there isn’t any age adjusting going on.

John Alcorn

May 24 2021 at 3:14pm

1. I would distinguish one’s resources (a) before government transfers and (b) after government transfers. A subset of the hard-case poor are those who fall through the safety net. See the surprisingly low take-up of government transfers by the bottom income decile in Figure 5 in Hilary Hoynes & Jesse Rothstein, “Universal Basic Income in the United States and Advanced Countries,” Annual Review of Economics 11 (2019) 929-58. (A brilliant essay.)

2. I would say that freedom fosters relatively broad prosperity. (A statement of cause-and-effect.) Limits to economic freedom make it harder for many individuals to exit poverty.

3. I would distinguish (a) momentary poverty in the normal course of life, (b) entrenched poverty (reinforced by culture), and (c) catastrophic poverty. No need to do anything about the first. Hard to fix the second unless norms somehow change. Some mix of competent government and philanthropy can remedy the third.

4. Children are innocent and vulnerable. A free and decent society must have institutions, norms, practices, discourses that prepare youths to stand on their own two feet, in the market and the forum. Smart material ‘investments’ help, but culture is crucial.

5. I advocate major experiments in radical vouchers for human-capital formation for teenagers, redeemable via apprenticeships, tutorials, internships, schools, training programs, etc.

Comments are closed.