| 0:37 | Intro. [Recording date: October 20, 2021.] Russ Roberts: Today is October 20th, 2021 and my guest is stuntman and action designer, Eric Jacobus. He spends a lot of his time choreographing violence and action scenes in movies and video games. Our topic for today is violence, based on a series of essays Eric has written that we'll link to. And, those are about helping us understand the how and why violence in human affairs over the centuries. At the end, I hope to bring the conversation around to how all of this infuses Eric's stunt work and work with violence in the visual arts. I want to start with a--so, Eric, welcome to EconTalk. Eric Jacobus: Thanks for having me on Russ. I've been listening for years, so it's exciting to be here. |

| 1:19 | Russ Roberts: That's great. I want to start with a quote from the opening of the essay--it's fantastic. You say, We hear this a lot: we humans are even worse than animals because we murder one another. That's a half-truth. It's true that animals don't murder one another, at least not very often, and humans do. The other half of the truth is that humans have created entire institutions to avoid violence at all costs. So, give humans some credit. Still, [you write,] the question remains: why do humans murder one another? Why do fights escalate so quickly? Why do we take revenge? And why don't animals do this? So, let's start with animals. Why are animals--which think of as: it's a dog eat dog world; nature red in tooth and claw. Animals fight. But, why does it--I don't seem to have a problem with escalation the way humans do. What's different? Eric Jacobus: I think it's more accurate to say it's a dog eat cat world because dogs tend not to kill other dogs. The thing about, would you say, intraspecific animal combat--let's say for example, if a lion were to fight a lion, or in your case, a dog is to fight a dog, a lot of the time the reason a dog can't kill a dog is because a dog is just sort of uniquely outfitted to prevent dying at the hands of another dog or at the paws of another dog or at the mouth of another dog. The natural protection that an animal has is sort of, you could say, designed to protect against intraspecific combat and to prevent death. But, even if you were to, for example, you were to have an animal that could kill another of its species, the question is would they actually escalate to that point? There's sort of two resolutions to this. The first one is that you'll have sort of an alpha/beta relation where a beta challenges the alpha and then the beta will back down. In the other case, the difference between humans and animals is that if a dog puts its paw behind its back, the other dog doesn't think that the dog has a shank behind its back or a shiv. It just thinks, the dog's got a paw behind its back. But, if a human puts his hand behind his back, you don't know if he's got a rock, a knife or a CD [compact disc] that he wants to sell you. And it's all based on intention. That is sort of going to dictate the course of events with human violence, as opposed to animal violence. Russ Roberts: And, my understanding of animal violence--not our focus today, but in case we have any animal listeners--my understanding of animal violence is it is frequently what we might call theatrical. It is maybe testing, pushing, looking for an opening; but they don't want to die. And evolution has created a certain set of behaviors on the part of animals that reduce the risk of death. An animal with horns can gore another animal with horns. And, they often will lock horns, but they often do that in competing for mates and other ways. But, again, it's a show. It's a little bit like a boxing match that human beings have. We also have boxing matches as humans. We'll get to that. But, as you point out, humans have this risk of escalation which is a deep, deep insight I had never thought of that fundamentally comes from the human ability to make tools. So, in the world of chimps or apes, more accurately, I think, an ape will kill another ape. It might use a rock--a tool that it has improvised. But, the range of tool-making among humans makes violence among humans very different. So, talk about that. Eric Jacobus: Extremely, because you could imagine that the first weapon was probably a rock and/or a stick, something that was just kind of found in the natural environment. If you were to try and reverse engineer this--and this is what Eric Gans does in his Originary Hypothesis. And, I recommend reading through his stuff because a lot of this comes from what he wrote. If you were to try and imagine the moment before somebody had the idea of picking up a rock, for example, well, nobody has the idea of picking up a rock. So, let's say you go back to your Originary scene--to use his wording--and you have like an animal carcass at the center and you have the alpha and normally you would have a beta fight the alpha; the alpha wins and divides up the meat as he sees fit. But, in the case of somebody--it might be the alpha, it might be the beta--putting behind their back and suddenly they have a rock. Now, it's as if now, okay, well, we no longer are simply anticipating that he has a hand behind his back--and this gets into the mirror neurons of it, which is that if you were to sort of virtualize the intentions of other people--and this is Giacomo Rizzolatti's work from Mirrors in the Brain--if you were to virtualize the intentions of other people: Whereas before the rock, we were just virtualizing a hand, but now we're virtualizing that they might have a rock behind their back and we don't know. That changes the game theory of the whole situation, because now, if you don't know if the person has a rock behind their back, then maybe it's best for you to assume that they do. So, you might as well pick up a rock and attack first. And that is the tendency to escalate. Again, this is not a variable that's within animal societies. I think only in extremely rare cases do you have certain monkeys, for example, using a weapon of some kind. But, I think even then in those cases, it seems to be almost accidental. It's almost as if maybe they're copying people--sometimes maybe there are animal experts could correct me. But, that fundamentally changes the equation. And, then perhaps then when you go into the Iron Age and now you have the ability to fashion sharp tools or even--like that's why you might have iron taboos, which are very common among various ancient societies. Having a rock versus having an iron knife, for example--it's a very different equation. And so, it's almost as if, as we go into these new epochs of having a new kind of weapon--the Stone Age to the Iron Age and then the firearms age--it's almost as if, like, we're virtualizing higher and higher stress, right? It's like the concern grows bigger; and then the concern becomes, like, 'I'd better or get mine first.' |

| 7:40 | Russ Roberts: So, that's the potential for escalation that humans often have, do escalate fights, do escalate into bloodshed and death. We're going talk about that. Those listening with small children may want to take care, because there will be some gruesome maybe, we'll see, conversation here. Let's back up and talk about mirror neurons, because that's something I--I know a little bit about it, but not very much. Mention the name again of the person who--they're not very--our understanding them is only about 30 years old, which surprised me. But, then I realized, why am I surprised? We didn't have much capability of finding mirror neurons until recently. Talk about that. First, just give us some basic information about them, because that part of this conversation is utterly fascinating because it builds a biological basis for things like revenge and violence and rage that I think we tend to think of as matters of civilization, self-control, intelligence--'a smart person wouldn't get mad over a traffic problem.' Just let's start with the basics of mirror neurons. What are they and what do we know about them? Eric Jacobus: The mirror neuron is essentially a function within a certain subset of neurons. Perhaps some people are saying that it's part of more than just the specific subset of neurons not just within the human brain but also within various other animals have this as well, which essentially functions as a mirroring mechanism in the motor system. It works through the--it's sort of simple in a way. If I could just explain how they were discovered, it'll actually illustrate very, very, very nicely. So, Giacomo Rizzolatti, who wrote this book--I pulled it out just so people can see it. It's Mirrors in the Brain, Giacomo Rizzolatti. He was doing a test on macaque monkeys, trying to figure out simply where in the macaque brain was the neuron center for various motor controls like grasping, pointing, making a fist, etc. And so, they had probed a monkey's brain, not a very animal-friendly thing to do, but they found that--they found the spot in the monkey's brain that grasps. Right? So, when the monkey went to grasp a banana, it would beep and it would have a little read-out. And, then the story goes that they left the monkey hooked up and then one of the scientists picked up a banana himself; and then the same beep in the monkey's brain read--in generally the same area. And that really changed the study. Right? Because now, the idea was that: well, not only are monkeys just coming up with an idea of grabbing and it triggers a neuron firing. Instead, it's also that: well, when monkeys perceive another person--and subsequently when we perceive other people doing something--then that actually trips that neuron within that motor system. So, just to give a concrete example, if I were to hold out my hand in a hand-shaking position and you are to perceive this, then what you're doing is you're basically virtualizing in your mirror neuron system, my intention to grab your hand. That will elicit--almost, in some people it might be just, it might just be involuntary--a reaction to just reach out your hand and do the same thing. A high-five with children: if you have small children, you'll notice that children high-five very early on and it's not a rational reaction. It's just that children, before the age of two or three, are just mirroring mechanisms, in a way, with a soul. And so, by performing the action--by shaking the hand, by giving a high-five--what you're doing is you're building the connection between the mirror neuron and the motor system itself. So, in a sense, you're actually training your body, not only to do the action, but to understand the intention of other people who are doing that action. And so, if I were to then put my hand behind my back, and I were to pull out flowers; and if I just did this your entire life, you would think that anybody with their hand behind their back, you're virtualizing as if they just want to present you with something beautiful. But, if you go to a war zone and somebody puts their hand behind their back or in their pocket and every time they pull their hand out, it's a hand grenade that's trying to kill you, well, then you are going to go back--you're being trained to virtualize people putting their hands in their pockets to do something very dangerous. And so, when you come back into civilian life, you are now trained to think that people putting their hands in their pockets--children, adults, whoever it might be--are trying to kill you. And so, the virtualizer is, like, really that sort of mechanism that trains you to react and understand the intentions of other people. Russ Roberts: When you say virtualizer, you mean just imagining? But, more than sometimes--in imagining we think of, 'I wonder if--' and you let your brain run free. This is imagining without consciousness. Conscious intention, is the way I would phrase it. And, the example you just gave with the hand grenade is I assume the way some people were thinking about PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Right? You're in a war zone, you see a lot of things that you have learned lead to violence and death. You come back to a place that isn't in a war zone, and it's important. It's not like, 'Oh. There could be things here that are dangerous, too.' It's that your brain doesn't think, it just--you don't think in a conscious way about that. You see someone reach into their pocket and you have a visceral reaction, is what I would describe it. That's what we're saying? Eric Jacobus: That's correct. Correct. Yeah. Russ Roberts: So, obviously children imitate-- Eric Jacobus: If I could add a caveat to that, too-- Russ Roberts: Yeah. Go ahead-- Eric Jacobus: It's also not simply you're reading the intentions of people. Because, we can see many, many, many examples--if we look back in anthropology, for example--of people trying to understand the intentions of the sun or an animal. Right? And so, we virtualize everything. Russ Roberts: A tree-- Eric Jacobus: By virtualizing it--yeah, a tree. Or the Creator, himself. Right? And so, if you're trying to then understand the intention of whatever it is you're perceiving, then you tend to anthropomorphize it because that's the mirror neuron system that you have. So, violence is anthropomorphized. There might be an object and so you can also--it's sort of: you're inundated by these intentions of even an object, and by seeing an object, even, or a location, that can have a similar response. |

| 14:32 | Russ Roberts: I think the point about intention is rather extraordinary because intention is--again, I think we rarely think about this in everyday life, but because it's so intuitive. I mean, it's so instinctual, whatever you want to call it. But, obviously, determining intention is an extremely valuable skill. You really want to know about the difference between somebody reaching into their pocket to give you some spare change on the street or to ask for change, versus somebody who is going to hurt you. And, naturally, we're going to have a bias toward hurt--because that's a good mechanism to have--but as civilization advances, we do, I think, learn that many of these gestures that might be alarming, we start to associate positive intentions with them. But, I don't think we can overestimate the importance of assessing intention instantly. The way I understand what you are saying about mirror neurons is that the speed of this is essentially zero--the time it takes to make these--we jump to conclusions because that's really a good idea. Russ Roberts: Sometimes. Well, I guess one of the questions would be when is that, when isn't it? But, I think the point about intention and that we are biologically evolved to both determine it, assess it, guess at it--and of course, provide it as well to others, right? Eric Jacobus: Frankly, I have no idea how the evolution of this could happen. It seems to happen, it seems to be a step nature. I can't even speak to the origin of it. But, what I can say is that the way that the understanding of intentions--or of intents, you could say--the way that you actually train yourself to understand the intents of others is by performing the same action yourself. So, for example, you were to go take a boxing class. The teacher is going to have you stand in front of a mirror and just throw punches. And this is like any martial art class: what you have to do is copy the teacher. And the teacher, presumably, is doing it the right way. And, what you find--so, your first sparring lesson, your first sparring--it's going to be a lesson, let's just say--your first sparring session is going to be the other guy hitting you in the face a lot, because you cannot read his intentions. But, what you'll find is that the more you throw the jab, the more you throw the cross--the boxing terms--the more that you throw these different attacks or whatever martial art or if you're in warfare, the more that you do this thing, the more you're actually able to read it in other people. And it's not even a--it's not at all rational. So, for example, this is why Muhammad Ali-- Russ Roberts: Conscious. Conscious. Right? You said 'rational,' but it's conscious-- Eric Jacobus: Conscious. Yeah. It's not even really conscious. It's, like you said, it's instantaneous. But, this is why when Muhammad Ali sees a punch coming, he can just move out of the way. Because, it's not that he sees a punch coming. It's that he sees a hip move. It's that he sees the foot pivot slightly. It's that he sees the guy blink a certain way. Because Muhammad Ali has thrown that punch more times than anybody else, he has developed enough action-understanding--in the words of Giacomo Rizzolatti--to be able to read the intention of other people. And that just comes with practice. And that's something that an armchair boxing critic will never be able to do. |

| 17:58 | Russ Roberts: But, when you say you learn to do this--you know, there's different aspects of practice. Right? Musical scales, say, if you're learning an instrument; you're grooving your swing in golf or baseball--these are forms of practice that are, as I understand what you're saying, different than these, say, the case of boxing. You're talking about the fact that your practice is doing something that you're not having, just not have to think about. You're tapping into this brain skill that allows you to not say, 'Oh, he turned his hip. That's a bad sign for me. I bet a punch is coming.' So, one way to think about that is: You just get better interpreting the hip. But that's--you're really trying to say something more than that. It's not, again, the way we might say, 'He brought me flowers. He must be making a friendly gesture.' It's something--again, there's not that conscious, step-by-step reasoning. Eric Jacobus: That's correct. I mean, the examples that you're giving are single-person endeavors, right?--golf and whatnot. You're not reacting to anybody. But in the case of boxing, you are toe-to-toe with somebody. So, baseball is probably another example. Football, too. The more that you practice with other people, the more that you can understand the intentions of the people around you. It just helps you sort of develop a virtual environment where you can take a snap shot of the x-number of players on the field and kind of know where the ball is going to go. And that's an extremely valuable skill. That comes with practice. Russ Roberts: But, it's more than that, of course. There is a biological--you might call it software that works the hardware. You know, someone like Wayne Gretzky who was legendary for knowing where the puck was going to be in hockey-- Eric Jacobus: Of course-- Russ Roberts: Muhammad Ali didn't just practice more than other people. He had better neurons, or whatever you want to call it. |

| 19:58 | Russ Roberts: The only thing I want to add to this before we move on--and we're about to move on to actual violence--if you know anything about mirror neurons, you probably know this already. I didn't though, until I read your essay. It explains, as you write why I cry when a fictional character has something bad happen to them or why when I watch someone absorb pain--a punch, a knife attack--I don't just have a mental set of reasoning. My brain hijacks my emotional reaction and I have a visceral reaction that I really don't have control over. It's a fascinating thing. I've always been puzzled by that. Why would I be sad when a person in a movie dies or is harmed? It's fiction. But I can't help myself. Eric Jacobus: Or when a cartoon car or robot dies, even, or an animal, or a tree. It goes beyond simply other people. Like I said, anything that you can virtualize, you're naturally going to have some kind of empathy for. Russ Roberts: And--I was just going to say, when somebody cries in a movie or in real life, I find myself often choking up and becoming emotional. And, I've always thought, 'Why is that?' That seems--I mean, I feel bad for the person, but why am I crying already, even though I just feel a little bad? But, if they told me something sad happened to them, I'd feel bad for them. If they tell me that something bad happened to them and they start crying, I suddenly find tears welling up. But, that's exactly what's going on here.Right? Eric Jacobus: Sure. Laughter is the same way, too. That's why they put laughter within trailers now. With comedy trailers, they'll have a joke in them, they'll cut the people laughing, which is just a really cheap way to try and get people to laugh at your trailer. But, that's like Mirror Neurons 101 right there. It's like, if you show people laughing, maybe people will laugh. And, I think sometimes it's true; and people who aren't really thinking about it, but I think so. I think a lot of the time, people want to be challenged. And a good, genuine laugh comes from having to sort of process two inputs and then it comes to an output and you have some kind of new logical combination of the two things. I think that the--but in terms of why we cry about other people in a movie, or with other people in a movie, for example, or why we follow the hero's journey--why do we care? And, also, why do we care that they die? They're fake. Why do we care that these things die?-- Russ Roberts: Yeah. They're fiction-- Eric Jacobus: People cosplay[?] as these things to sort of keep them alive. It's just almost like new kind of ancestor worship, in a strange way. And, it's because--you know, if you go back to the Greek theaters, if you go back to just ancient sports, the fact that the sports were always played with the crowd because that was a very cathartic moment for the crowd to witness. And, I guess you could say the crowd was all virtualizing the intentions of the hero--and also the villain--but they're associating with the hero because of whatever cultural inputs there are going to be, where that's sort of the framework that it's presented to you. And, when the audience is virtualizing with this character, then there's this--you call it, again, the hero's journey--that you go on with them, where you just--they kind of take you for a ride and they hook you. And this is also how cult leaders work. This is how hypnosis works. This is how a lot of things work that can also be very, very harmful if we're not careful, if we let ourselves be sort of strung along. Or even narratives that lie. I mean, if you are watching a film about the plights of a poor man, and he's poor and he's crying and he's got no money and his children are dying and you show that the fault is the Jewish guy next door--it's like, well, 'Wait a minute. Now you've now you've taught people to be antisemitic via mirror neurons.' This is also--it could be used very badly. It could be used for evil, a 100%. And it has. And that's what propaganda does. |

| 24:07 | Russ Roberts: Fascinating. Now, we talked a minute ago about the rock versus the flowers. Just for jargon and vocabulary, talk about the difference between closed versus open altercations. And, altercation is a funny word. It's like a police notebook word. An altercation can be a shoving match and it can be a fist fight and it can be something much worse. What do you mean by a closed versus an open altercation? Eric Jacobus: Well, a closed altercation is going to have some kind of external suppression to keep things from escalating. So for example, a closed altercation would be sparring between martial arts in a school, a sport, some kind of--something that's either for teaching or for cathartic ritual, maybe both. And, it's an outside mediator ensuring that the two parties or more don't fight to the death. There might be some level of escalation. Interesting--you had an episode some time ago, I think with Mike Munger, about fighting within sports, which I found so fascinating. That really helped actually, at the beginning of this theory, to just understand, like, where the confines of this closed system and that there's this kind of hernia that happens when somebody rushes the mound, for example, or when you have a fist fight within hockey. They sanction this stuff to some extent, and other times not anymore. They'll change the rules depending on--who knows?--some kind of fallout, for example. But, if they find, for example, in hockey that these fist fights are really good ways to generate revenue and they don't sort of bleed over into the audience--right?--because that's kind of the risk of an open system is that if you're allowing fighting to the death, well, if the audience then is virtualizing the main character in the combat as he's going to die, they might take it upon themselves to think the same thing is going to happen with them, with their neighbor next to them, for example, or when they go home or the next week. It's impossible to really know the full effects of violent entertainment on people because it's probably different for every person. It's different for every location. It's going to be different if there's one person in the audience versus 10,000 people in the audience. There's so many factors and that's why--I can't take a political stance as to whether or not violence and media is good or bad. I don't know if it stops people from being violent or if it promotes violence. It's impossible to know that. All I can really say is that: Here are the mechanisms and here's probably why we go to these things is to sort of virtualize with the character. There is this sort of cultural--what would you say? It's almost like acculturation that you engage in when you watch an actor go through this hero's journey, whether in sport or film. And, that ends up being a very common cultural tool that we use for people. |

| 27:04 | Russ Roberts: But, in sports--and a lot of that episode [Michael Munger on Sports, Norms, Rules, and the Code--Econlib Ed.], which I also love--was about the explicit formal rules, what we might call the legislation, versus the norms or laws that govern and restrict that violence. So, in case of hockey, two people might fight, but it's against the rules. It's probably literally against the rules, but it's certainly against the rules, the norms, for one of the teammates to say, 'My teammate's getting beaten up. I need to go out there and help them beat this person.' You're not allowed. It's a duel. We'll talk about duels in a minute. Duels are a fascinating, I'd never thought about them as you do, which I really appreciate and enjoyed, but that was about the fact that these norms are restricted, often restrict that violence to a very narrow channel. What it encouraged me to think about is the spectators. And, as you say, it might be cathartic for some; for others it might be inciting. I remember being in high school--it happened to be in Israel. I was in Israel for high school and for eight months when I was in my junior year. And our team was playing some team in basketball. And after the game--the game was over--I think we'd lost. It was a home game. And, the fans and the players were all kind of milling around outside the gym. And something--there was a violent thing. I don't remember what it was. Somebody shoved someone, someone may have said something that led to a threat. And I suddenly found myself--I can't tell you how rarely I've ever been in a fight. I've been in a few, but all when I was younger. But, at that moment, as a semi-adult at 16 or 15--16, I think I was 16--I felt an enormous surge of adrenaline, or something. It did not come from me observing this and saying, 'That seems like that's an injustice.' It came from everyone around me. There was a mob rule. It's a standard cliché. But, what you're suggesting is that when I saw my neighbor rise up in anger, I mimicked them. I mirrored them. I didn't say, 'Oh, I bet something really bad happened. I should find out what it is. And, if it's important, I'll do something about it.' I just wanted to hurt someone. And, that's when I realized, as you talk about a lot in your essays, this is deeply embedded in us. It is not conscious. It is not something we have full control over. Obviously, we try to control it in ourselves, but it's deep within us. Eric Jacobus: And it might be the first crisis, as far as we know, because the propensity to engage in mob violence, as you say, it's almost built in to combat right away. If we go back to that Originary scene with the hand behind the back as the subject, then if you decide, 'I'm going to pick up a rock and do this first,' you can almost imagine then everything just descending into chaos and everybody potentially dying. 'This could be the end of us, if we do this.' And, so, that's what an open system would be, where there are no external rules on this thing. Where it can just explode out of control. This is why we try and impose global rules on combat work. Russ Roberts: Warfare. Yeah. But, talk about what you call the contagion of violence, because I think that's a nice way to think about the escalation. It's not just two people, one says, 'That might be a rock. I'll go get a rock or I'll grab this rock that fortunately is at hand, because I need to defend myself.' It spreads more widely. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. It would work the same as--you could almost say that germ theory is founded upon this idea. Because, before germ theory, the theory was that plague was a spiritual phenomenon and that was the commonly accepted understanding of where plague came from. And, a lot of the resolutions to plague were--you know, the rituals they would employ--were the same rituals that they would employ in order to make sure that they won and warfare or as a way to sort of tamp down human violence as well. So, it was all kind of treated as the same sort of spiritual malady. And, you know, if we were to try and understand this from a scientific perspective using mirror neurons, then it's that: Well, you can have--you can virtualize more than one person for sure. You can virtualize a lot of people. In fact, if you start running a simulation in your mind of all the people around you--and presumably you know the people around you. And, by the way, in that situation that you talked about, you all have kind of come out of some kind of a cathartic ritual of some kind where you're all sort of on same page suddenly. Right? And so, if you were to watch a movie with your friends and you all come out and you're all kind of on the same heros' journey in a sense--now, in the movie, they tie it up. There's an ending to it. So, it's supposed to be over. That's what the credits are for. But, sometimes perhaps, it's not tied up very, very nicely, and so you're still virtualizing: So, okay, well, there's still some kind of end to this that hasn't been reached yet. If that end is achieved by the crowd and you can virtualize that end and you can be a part of it, well, that cathartic--and you talk about the adrenaline rush--well, after the adrenaline rush and after you beat down the scapegoat in that case, for example, where if it's group versus group, then there is this sort of cathartic feeling of, like, 'Yeah, we are assimilated as a group.' And that is really what you're trying to go for--is this fraternity with other people where everybody is now-- Russ Roberts: It's the tribal--it's the tribal issue we've been talking about in this program recently over the last couple of years. You know: 'They're my team.' Literally, in this case. Eric Jacobus: Of course. Of course. And, we can't give a normative statement to that because it causes some ills, and it causes some great things, too. It helps for amazing organization. |

| 33:43 | Russ Roberts: But, talk about--what I wanted you to talk about, if you could, is that this idea of the feud; and how, you know, someone in that rock-on-/hand-behind-the-back-altercation gets hurt or killed, what that leads to and the way that human societies have tried to respond to that. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. The first example I can think of that comes to mind of the resolution to the feud is the mark on Cain after Cain kills Abel in the Bible. Because, after he killed Abel--he murdered Abel--the idea and his fear was that he was going to be avenged. And so, the mark on him signified that nobody will avenge the death. And that was sort of like the first instance recorded in the Bible, for example, of a way to stave off the feud. Because without that what you have is: if one man kills another, let's say--and it can even be in a closed duel for example. We can talk more about the duel later. But, let's say it's even a sanctioned duel: There is every--there is obviously potential for another party to-- Russ Roberts: Retribution-- Eric Jacobus: Of course. The retribution is simply--I mean, what you're doing is you're virtualizing. So, okay. A man comes into town and he kills a man--another man, the victim. And so, the victim's cousin is saying, 'Well, this man who killed my cousin is going to keep killing other people.' Like, it doesn't stop there. Unless there's a closed system around it. Unless it's very clearly outlined that this was duel, and this man who won this fight has no intention and is legally barred from doing any further destruction. Without that, then it's anybody's guess what he is going to do next. And it's just very natural then, for the people who are closest to the victim--who are going to sort of, like, you know, empathize with the outrage of this all the more--are going to be the ones that reach out to try and seek revenge first. And it's very common then, of course. Why do it alone? Why not just go with all your cousins and take the guy out yourself? And then, three fights--one and then his cousins come back with nine, and then now you have an escalation, now you have tribal warfare. And potentially world war. |

| 36:04 | Russ Roberts: Well, it's a common--it's the human condition. What's fascinating is that there are cultural norms and institutions that try to limit that. Talk about--we tend to think of dueling as sort of this barbaric thing and especially after Hamilton [Broadway show based on the life of Alexander Hamilton--Econlib Ed.], which is a very moving and tragic--there's a couple of tragic and unnecessary deaths, it seems, unnecessary deaths in Hamilton. So, dueling on the surface seems barbaric--as do many other institutions. Boxing being one; hockey, football, etc. But, let's talk specifically about the duel. Why is the duel a good thing? Eric Jacobus: The duel is a good thing. If I were to defend the duel--the duel to the death--presumably in that it really seals up the matter. And the offender--the offender is not going to offend anymore. Or the accuser is not going to accuse anymore. Traditional dueling--it was actually rampant in France, I believe, in the 1700s. And Louis the 14th really tried to outlaw it. But it just kept happening underground all the time. And dueling was so important not just for settling disputes, but also for finding mates. Apparently women prized men who were good duelists. There's stories about these men who were otherwise very slovenly and not very attractive at all--I mean, they were really terrible people. But, the fact that they had such a high kill-count made them very attractive. It's hard to know exactly what the mechanism was there. But, perhaps we have a system there where the duel is a far-preferred system than the feud, because the feud can spiral out of control and the duel is just extremely closed. Russ Roberts: The beauty of it, which I'd never thought of, is that it's this an additional norm that it's understood that, as horrible as this is--because there's not unreasonable chance, even it's not a duel to the death--there's a not an unreasonable chance that someone is not going to walk away alive after this is over. But, at the same time, there is a norm that says, 'This is it.' No more. It's just a one-time thing. And you don't then get to count, get to challenge the cousin to a second duel, a third duel. It's just, it's quite--I'd never thought about it. I just want to add one thing before we go on, because I don't want to forget this. You'll like this. One of my favorite movies is Yojimbo by Akira Kurosawa. I suspect you've seen it. Correct? Eric Jacobus: It's been a while. I've seen it, yes. Mm-hmm, yes. Russ Roberts: Yeah. So, I remember watching--I watched that movie in New York City when I was in around college age, maybe high school. And I walked out of the theater; and I was so fired up. I ended up walking--I was with a buddy and we walked, I don't know, I walked maybe 100 blocks--a long way, with immense amount of adrenaline: that, that movie just made me want to--I just felt, like, powerful. Again, it's just a movie. But, I think a lot of these--actual violence stimulates these strange biological things inside us that we don't fully--are conscious of. Eric Jacobus: I think what it--I'm sort of being-- Russ Roberts: I felt like: Let's fight somebody. Which is really weird. Again, I'm not a fighter. But, I said to my buddy, I was like--I didn't mean, literally, 'Let's go start a fight.' But I felt invincible after watching the Samurai warrior in that movie. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. It sort of legitimizes this view that, 'Well, we could actually end a feud right now.' Because, everybody's walking around with various, you know, things dragging them down--various grudges that they're holding--and you don't like your boss, your coworkers are annoying, maybe there's something with your in-laws, or whatever it might be. And, so, this idea that you could settle things with a sword or with a gun. Gun-slinger movies do the same thing. It's really kind of the same code. And, this idea that you could end the dispute. And, by the way, even though in samurai films, it almost always ends in somebody dying. When I was taking sword--Japanese sword--my teacher told me that a two-inch cut anywhere on the body was lethal, back then-- Russ Roberts: Because of infection, presumably, yeah-- Eric Jacobus: Infection. Yeah, exactly. Or maybe the suturing wasn't as good. Who knows, right? But, when you look at--even the early 1900s, there are old films of people still sword dueling. You can watch these. And, they don't normally end in death. They end in a cut on the wrist. It's usually what happens; and that's usually the end of it. It seems as though that kind of situation, even though you may not die, even though there may not be a dead body at the end, the fact that you are anticipating possibly dying, that does something to you when you enter these equations. Maybe you're not even imagining that you might die. Maybe you think you're invincible. And then they cut your thumb in half and you go, 'Okay. Wait, I'm not invincible. Okay. You know what? It's not worth it.'-- Russ Roberts: I'm done-- Eric Jacobus: 'We're done.' Like, I'm not going to complain anymore. I'm not going to insult your, whatever it is. Right? So, yeah, that taps into something that's very deep within us, which is: if you were to imagine again, going back to the mirror neuron virtualizer, it's so open-ended all the time. For example, when a relative dies, all the things that they wanted to do, all their intentions, all the things that they wanted, you download all that without knowing it. And it's almost like the whole community might download this person's intentions. They might all have the same dream about the guy. It's very powerful. And the ability to kind of sew that up--to end it, to blunt it, whatever it might be--the duel does that. That's incredibly powerful. And that's why you kind of go around and go, 'Yeah, let's go have it out. Let's finish this.' Because men--like, how cool would it be to not have to worry about the grudge that you're holding against, you know, such and such person? |

| 42:31 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. Well, it's just that--I think--I'm a big fan of not holding a grudge, in theory; and a big fan of not taking revenge, in theory. You know, people have insulted me--on this program actually. Not often, but occasionally I've been insulted. And, I work very hard to not respond to the emotional risk response that that stimulates. I've learned to observe it in myself; and it's a fascinating thing. You are incredibly vulnerable in those moments--or dangerous, right? I think we have two sets of reactions that we've kind of glossed over. You either escalate: 'Oh, you've insulted me? I'll insult you.' Or, 'You coward.' It's kind of a alpha/beta male type of--it's usually men in the monkey troupe or the animal troupe--you cower. And, the challenge in those situations, I think, is to find, for me, is to find a middle path. I don't want to scream back at my guests. And, many listeners say, 'How could you take that? Why didn't you answer?' And, the answer is I don't want to do that because that does the next--then it just--not fruitful, not productive. But, the other--the loss of self that sometimes--it's kind of, actually, what it really is, to just be creative about what you're talking about: It's kind of like my brain saying, 'You don't want to get in this fight because you could lose and die.' So, when someone insults you, the best path is to take it, be humiliated, signify humiliation. Because then it's over. You're not going to get hurt. Which is often not productive in human conversation. And it ends conversation in a different way than the escalation does. You need to find that middle path. What I've tried to do is to be sensitive to when I see that and go, 'Oh, this is one of these things where I'm emotionally way over-involved, relative to the actual content.' Sometimes it's a misunderstanding. It feels like an insult. Right? But, a lot of times it's an insult and when you can learn to just sort of let it slide off, it's really quite liberating. Eric Jacobus: I think that that's--the de-escalation strategy is what you're talking about, where somebody really wants to go somewhere that's bad. Like, they want to go to a fight. They want to get into a shouting match because that's what they know. That's how they know how to deal with conflict. Perhaps in that person's mind--and I've had this happen: a colleague of mine who was stunt-coordinating a shoot that I was a stunt man on--so I was under him, and he would do this where he would engage and I couldn't deescalate. I just couldn't do it. And, then at a certain point, I'd just started shouting back; and we would have a shouting match. And at the end, he respected me because I met him at that point. So, like, that's the other danger, is: are they going to bring you to a point where you don't want to go? And, you have a loss of self. You've become that person, which is that classic mentor/student relation where it's like they're trying to amp you up, they're trying to do this and that. Maybe you need that. Maybe it's not good. Maybe you just walk away and you say, 'I need a new teacher.' Russ Roberts: What was the movie about the drummer? I'm blanking on it. Russ Roberts: Whiplash. Yeah. That's an example of, basically: I'm going to push this person's buttons, perhaps as a way of motivating them to be better than they can think they can be. But, there can be some sadism there, and cruelty obviously, and a feeling of control; and it's fascinating. |

| 46:08 | Russ Roberts: I want to talk about blood and the color red. We react, again, very viscerally to blood but in different ways, I think. So, talk about what your thoughts are. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. The color red means all kinds of things everywhere. In China, it's extremely lucky. Red is a good color. In India, it's somewhat taboo. They change it for a kind of a yellow color. But, then you look at something like these festivals where they throw tomatoes at each other and you wonder, like, 'Why are they throwing tomatoes at each other in Spain? What is it with all this red imagery?' Everybody's blood is the same color. I don't believe the conspiracy theories. And, the sight of blood--the thing about blood is it will--in your mind, and you--we like to think that we're beyond this Russ, but I just don't think we are. I really don't think we'll ever be beyond this: this idea that blood is purely a chemical within your body. But, you see it in children. When they see blood, like, something happens. There's something else that happens to children. And, you see it, too, within ancient societies: that, the sight of blood--and it could be blood on a weapon, it could be blood from a wound--it's going to elicit some kind of a contagious response, because what tends to happen in ancient society is that when you have, say, for example, you have a bloody weapon, that tends to connote that there's some kind of violence at hand. And that violence, within all of our minds, is contagious to some extent. So, that's why weapons that are soaked with blood have to be--they have to be cleansed before they go back into the vicinity of the tribe. They have to be cleansed: they have to be kept outside for seven days, purified, etc. And, people who have blood on them, they have to be set apart. It's a very kind of strange and old way of thinking but I think that it taps into sort of the reality of what blood means to people, which is that it's some kind of sign of contagion. And, sometimes that's ill-founded. The sight of certain kinds of blood is not actually contagious. They might actually ascribe the incorrect prescription for seeing blood. They might imprison a young girl in a house for months on end at the sight of blood, and that's not a good thing. I can't imagine that being a good thing because the sight of blood in general does not always mean violence, but that can perhaps help explain some of these-- Russ Roberts: Better safe than sorry was the ancient-- Eric Jacobus: Better safe than sorry. Perhaps, yeah. They probably ascribed some kind of real connection between blood and violence, or blood and plague, blood and injury. Sometimes that was ill-founded. I think sometimes they might have been on to something. But, I think it kind of helps understand, like, why they did certain things with regards blood and red things in general. Russ Roberts: But, the challenge for these kind of ideas--and I find them interesting--but, going back to, say, a ritualized fight like a boxing match or a fight in hockey, if that becomes bloody--like when a fighter takes a hit that in boxing that causes blood to flow--the crowd--well, I mean, it's a hideous thing as we step back and observe it from a distance--the crowd will often roar as an approval that the good guy is, or the person they're rooting for, is winning. What you're pointing out is that it's a lot deeper than that. And yet, at the same time, there are people who, when they see blood, get faint. They don't get angry, they don't get violent. They go to give blood and there's nothing, it's a purely clinical thing. It actually doesn't hurt anymore. The needles are really sharp, and there's really almost very little pain involved. But emotionally something else is happening there and they, quote, "can't stand the sight of blood." So, how do we think about these two extremes where we see blood and a huge emotional surge of anger, and triumph, and violence surges within us--which is why those taboos that you're talking about from ancient cultures were often there, at least that's your claim; it's interesting--versus the person that goes, like, 'Oh my gosh, blood. Oohhh,' and they run away? I once babysat for a kid who was a little bit of a thug, literally. He was a kind of a bully and not a nice kid. But, he was--anyway, it doesn't matter. He got into a fight while I was babysitting him. It wasn't actually a fight. He was just swinging a stick with another kid. They had a duel. Right? And, in the course of that, his lip got cut open. That ended the fight. And, he was, like, totally blasé about the whole thing. And we went inside to clean him up, and he saw his face in the mirror, and he burst into tears. And I couldn't understand why this incredibly tough kid--he was eight--suddenly had had this emotional reaction. He didn't look good, but it wasn't that horrible. But it was the blood. And: How do you understand those two extreme kind of reactions of, like, again, total cowering and weakness versus incredible anger and a surge, an urge for violence? Eric Jacobus: I mean, there's a--and you see it, too, within people who are, for example, protesting vaccines. For example, where you might have this sort of aversion to anything being done with your blood. And, this goes into a lot of Departments of Anthropology, where blood is the life. I mean, the reason that people would drink the blood of their slain foes was to obtain their life. This is why the Aztecs when they would sacrifice humans and they would drink the blood out of the heart: they were attaining the life of the person. That's why when the Maasai drink the blood out of a cow: they're getting the life. The idea of life being in the blood is a very--only recently have we tried to dispel this idea, but it seems to be sort of active and very well alive within children-- Russ Roberts: common-- Eric Jacobus: Yeah. I mean, even within children, you don't have to tell them anything. The fact that they see blood--like, nobody ever told that kid that if you see blood, you should freak out. No kid is--I've never seen a kid very curious about seeing blood and going, 'I wonder where that came from.' It's like they all know, somehow. All I can say is that there is some kind of deep-seated understanding within people that blood is incredibly important, and that it may be not as mechanical as we're making it out to be. |

| 52:57 | Russ Roberts: But, do you see fighting, ritualized fighting--and we're going to now turn to your work--do you see fighting like boxing, hockey, and etc., do you see that as an institution to reduce violence? Because again, I'm not--it seems to me it could equally be argued that it incites it. Do you feel that those ritualized--I mean, boxing is just letting us watch a duel that's not to the death. It is tragically sometimes to the death, but the idea of it is that it won't be to the death. It's just--there's certain rules, once you get knocked out. There's the idea of a technical knockout--you don't have to literally be knocked out. What are your thoughts on that? Eric Jacobus: I mean, unfortunately the deaths in boxing are usually very prolonged and traumatic and go into retirement from brain trauma. What's interesting, when you look at the rules of boxing, the addition of gloves to the sport of boxing--because boxing used to be with bare hands or they had very small gloves--and that was to protect the hand. It wasn't to protect the face. And, drawing blood was common and normal. And, at a certain point, there was this aversion to and then they basically-- So, now when you have a boxing fight, yeah--when somebody draws blood, the crowd goes, 'Wow!' But, what happens? You get the cutman on it, and if that cutman can't seal up that cut, what happens? The fight ends. And that's a standard set of boxing rule: is, like, 'We're keeping this clean.' My only assumption is that they're kind of tapping into some kind of deeper understanding that blood is contagious upon the crowd. Again, we can't track it with data, but we could just look that when you see blood, the crowd goes wild. It's interesting to look at something like MMA [Mixed Martial Arts], where blood is allowed, but it seems as though they've sort of figured out a formula where they allow blood, but the crowd is not any more riled up than a boxing crowd, it seems. Like, I've not heard of riots after an MMA match. And, if there are, maybe it happens at the same rate as boxing. I'm not sure what the numbers are. But the fact that you have explicit amounts--it keeps the blood in MMA fights versus almost none in boxing. And that the outcomes of the two crowds are not all that different, it kind of says something. So, again, I think that the idea of blood can be, for the crowd, can be a very cathartic experience, maybe under certain equations. And, it might be a very insightful experience under other equations. Perhaps--and I don't know--but perhaps the sight of blood within boxing is very insightful, but the sight of blood within MMA is cathartic. I don't know. All I'm looking at is that one allows blood and one doesn't. Russ Roberts: But, I do think, to take another way of thinking about this, when we think about the Roman gladiators and the Colosseum where crowds of people watch death as a form of entertainment--death--not just fighting. Death. They watched people mauled by animals. And clearly, it's part of the appeal of--bull-fighting is the risk of--and maybe NASCAR: It's the risk that death is hovering over this. And that adds a certain frisson--I don't know if I'm pronouncing it correct, a certain frisson of intensity. Like, 'Pay attention. Something here is happening that's serious. Don't miss it.' To a world of, say, football where it's still gladiators, but the death is, thank God, very rare, but there's a lot of violence. And it's a brutal sport. Is that a way of channeling our urge to watch actual death, which the Colosseum took advantage of? Do you have thoughts on that? Eric Jacobus: I don't know if we have an urge to watch death. I think--I don't know if you can isolate that variable. Because, did the first man want to see death? I don't know. Do animals want to see death? I'm not so sure about that. Do we respond to war and death? Yes. For example, if you have--there was a, I can't remember the name, but there was a Greek tragedy actor who did a--I think it was called "The Assault on [inaudible 00:57:32?]". It was about the Persians attacking Greece. And, it was such a fresh event in the minds of the people in Greece. And he did the play, and the people rioted, and they outlawed the play. They wouldn't let him do it again. And they fined him, because it was too fresh in their minds. However, perhaps 10 years down the line, or maybe there's like a--maybe in the case of the Roman gladiators, right? And, you're imagining the citizen in Rome is sort of--from what I understand about the Roman empire is that the citizen was pretty distant from violence, to some extent. Violence was all proxy. It was all done with their armed military. There wasn't a draft as far as I know. I'm no expert on Roman history, but my understanding of warfare back then was that, like, warfare was done by warriors and soldiers--to use your recent example of your recent guest-- Russ Roberts: That's Bret Devereaux's episode-- Eric Jacobus: Yeah. And, so, it could very well be that what we might consider a thirst for violence might simply be us still virtualizing the previous crisis in our minds--the previous violent crisis--and trying to sort of interpret reality through that lens. Because that is a lens of PTSD [Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder]. And, we can get into concrete examples if you want. Russ Roberts: Well, I think it reminds me of a family member--who is not my immediate family, but I don't want to identify them. This person was, like, six years old; and she went with her mom to a movie, and there was a wicked character in the movie, a really frightening monster-kind-of character. And, the six-year-old said to herself--her mom heard her saying this, is where I've heard the story--'He's nice.' Well, he wasn't nice. But, she was comforting herself. And, she said it more than once. 'He's nice. He's nice.' Eric Jacobus: Okay. Gotcha. Russ Roberts: And, I think maybe some of what we see as ritualized violence--some of the ritualized violence that's part of our culture throughout human history--is a way of comforting ourselves that, you know, 'This is violence that's not going to kill me. This is my way of saying it's not going to--that contagion is not going to spread beyond the arena.' I think that's part of it. Eric Jacobus: That could very well be. I think it's also--it's also a very potent antidote to a perceived villain, for example. You look at the history of the WWE [World Wrestling Entertainment] and how they integrated a lot of sort of archetypes of foreign characters--the Iron Sheik, for example. They sort of provide a proxy scapegoat in a way, where the current--whatever the current crisis might be, that this character is going to allow you to dump all of the intent load into this character and say, 'Yeah, that guy is the bad guy.' And, the villain in your movie, the villain in your favorite TV show, presumably has some kind of connection with a real world villain in your brain, whether you're conscious of it or not. Otherwise, I don't know why else we would be watching cathartic entertainment--probably in higher volumes than we ever have. I've never heard of the idea of binging a TV show before today. It seems as though we do it more than we ever did before. Russ Roberts: Well, it wasn't really possible. But--we didn't have--you couldn't watch 23 episodes in a row. But, I do think it's an interesting question of why we binge-watch generally. It's not obvious why it would be something you'd want to do, but we're clearly--for good; and violent and nonviolent shows. |

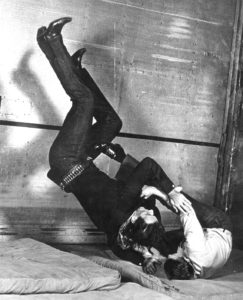

| 1:01:31 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about your work. Let's talk about the economics of violent entertainment, which is part of what you do with your time in video games or as a stuntman or as an action designer in movies or video games. How does what we've just talked about have to do with what you do? And, how do you think about it? First, tell us some of the examples of what you've done in your career with this kind of ritualized violence on screen. Russ Roberts: Like, martial arts is very different than a real fight, in most of the time. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. A recent example is I action-directed an Indian film called Man Who Feels No Pain on Netflix. I did motion capture for God of War, 2018--which means I put on a suit and performed combat movements for the character. Recently we did God of War, Ragnarok at the studio. And, the--what I tend to do with these projects is, they will ask me, 'How do we design action for this that's very compelling?' And, you know, action is synonymous with violence, right? It's kind of the same but different, in a way. Action is just kind of like a non-normative term for it. What I'm trying to do--so, what I'll do is I'll give a presentation for these companies that want to hire us. And I'll basically--the thesis is choreography is planned movement, and action-choreography is planned violence. So, if we want to understand action, we need to understand violence. And, I'll sort of take them down this--it's not so dark, necessarily, as I think it's introspective for a lot of them. And we'll go through basically the same thing we've talked about. And what we'll do in the end is we'll try and come up with some kind of a system that is going to--I call it an action code, which is: How your performers move in their action scene, the fight choreography, how violent are we going to make it? Like, how cathartic does it need to be? Does it need to be funny? You know: Is it for kids? or is it very dark? I also have my limitations. I'll only go so far. How the camera also perceives the action and how--even if, if there's editing, for example, in the movie or the game, like in a cut scene, for example, how that--and how all that stuff comes together to create some kind of an action code, that's going to interface with the audience in some way. Either they're going to respond to it or they're not. Depends on their demographic. If it's a franchise, say: Well, who is your audience and what do they like? What don't they like? Do they not like--you could have the same audience watching Harry Potter films and at the same time playing God of War games and they'll have very different expectations for how that violence should be. You shouldn't be putting Harry Potter violence into God of War. It's just not going to work even though it's the same people doing both, playing both. Russ Roberts: And, vice versa. Eric Jacobus: Exactly. And, so that--creating that action code is also, like: How do we know how people are going to respond to action? Like, when they see violence on screen. And, just to use a personal anecdote, I come from a family that watched a lot of Marx brothers and Laurel and Hardy and Charlie Chaplin. I was very much a fan of the performative style of comedy and just in theater. So, I liked Jackie Chan films, because Jackie Chan, the camera was wide, there's not much editing. You can sort of see him just doing the thing. Right? And, you know, that's how I kind of came up as a fight choreographer and filmmaker. And, then something changed in 2002 where the film Bourne Identity come out. Maybe some people watching this have seen it or heard of it. And, the action scenes in that movie were very innovative in the way that the camera was very shaky. The editing was very--I don't know. It was confusing a lot of the times. It was difficult to see what was happening. And, at the time, I reacted negatively to this because it went against everything that I believed in when it came to action. But, then after doing this presentation, I started realizing that maybe there was something to that film, because Bourne Identity was in 2002 and that was hot on the heels of a major catastrophic event in America, which was 9/11 [September 11, 2001--Econlib Ed.] And, you know, I think that everybody at that time was a little bit concerned about going on airplanes. Probably took a few years for that fear to go away. And again, that's intent loading. You're in the intent load that you're--and it might be overblown. I think it was obviously overblown to assume that every Muslim was going to hurt you. Right? And this caused a lot of unfortunate victims, which is, like, awful. This is where, again, the mirror neuron system can go crazy and sort of like over-virtualize. Russ Roberts: And, this is the whole challenge of, quote, "the other people," who aren't like you, aren't part of your tribe. How do you treat them in a civilized way? My person[?], by the way, is that a few weeks after 9/11, I flew to Athens, Georgia--University of Georgia--I didn't fly to Athens, I flew to Atlanta and took a van to Athens to give a talk at the University of Georgia. And, my wife was very worried about--as I was a little bit worried about the flight--but of course the van ride was much more dangerous than the airplane. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. Much more dangerous. Russ Roberts: Oh, for sure. But then, the part I also remember is I got to the hotel and the person at the hotel was very, very eager to be careful about my license plate and checked who I was. And, I'm thinking, 'You know, you're really not--you're probably not going to get a terrorist attack in Athens. It's a small town. It's not likely to be a target.' But, it didn't matter. People were so, quote, "paranoid." Not paranoid, not even overreacting, but re-acting, I think is the right way to think about it. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. Well, you could say that if we didn't have globalized media, if that had been a local news story in New York in 1950, then you wouldn't have had that issue in Athens-- Russ Roberts: Correct-- Eric Jacobus: But, now, a pebble--and so now if you throw a rock through a window in New Zealand, then suddenly people in California are afraid of their windows getting broken. And it's just global media tends to do that. It tends to make of our intent loads converge on the same crisis--in which it's going to be overblown, no matter what, like, for sure. But, just getting back to the example of 9/11, when you have sort of a--it was really a global, kind of shared crisis. A lot of people around the world--everybody saw it happen. This is sort of at the beginning of the 24-hour news cycle back in 2001. It hadn't been going that long: the world had been fully globalized. And so, via the entire Western world, sort of understood violence in a new way after that happened-- Russ Roberts: Yeah-- Eric Jacobus: And, when you are virtualizing violence or anticipating the intentions of people differently. And that'll sort of do things to how you perceive action. And, so, this film Bourne Identity comes out--and I don't know if they meant to do this, I don't know if it was intentional--but the style of action in the Bourne Identity is much more evocative than showy. And what you're doing is you're evoking a very dangerous situation that's very difficult to understand when you're in the middle of it. But when you come out of it, you sort of reflect on the images and you realize, 'Okay, well, I'm glad Bourne got us through that,' because you didn't quite know where you were in that whole action scene. And that's one way, for example, that you could design an action code based on the previous crisis. And maybe that's healthy. Maybe that actually helps people to compartmentalize the PTSD of a previous crisis into the more rational parts of the brain. |

| 1:09:34 | Russ Roberts: But, I don't remember The Bourne Identity. I don't even know if I saw it. I think it had Matt Damon. But I'm thinking about--I don't like violent movies. So, my wife and I tend not to watch them. But, there's certain violence that I don't mind. I would call it stylized violence, which is a way of saying--I think what I think I was hearing you say--a Jackie Chan movie, isn't actually creepy. It's dance, in a way. It's a performative. You and I are calling it choreography. In that case, the choreography is almost explicit. It's a little bit like wrestling. We understand that it's violent, but it has been planned. That what you're saying about the Bourne Identity, it sounds like, is it's not planned. It doesn't feel planned. It feels more like real. And therefore, it has a very different impact on the viewer. Is that what you're saying? Eric Jacobus: That's correct. That's correct. That has become the gold standard. And it's been the gold standard for a long time within my industry--is that trying to design action that doesn't look choreographed. And there are other films, too, like The Raid, for example, that kind of taps into the brutal nature of violence rather than the dancing nature of it. John Wick is another example where it's still aesthetically beautiful, but there is sort of this still concern that one shot will kill and that he has a limited number of bullets in his magazine and they keep track as the filmmakers, because this is made by stuntmen. And so, there's a whole spectrum of violence that you can explore when you're making an action code. And, don't get me wrong, even after 9/11, you can still go back and do the Jackie Chan style of action. You look at The Matrix and Star Wars films that came out after 9/11. They didn't look like Bourne Identity. They were still the same kind of action as they were before. Perhaps the code of those films was not as evocative as the Bourne Identity, because I think as we see it--you know, the film, like, Taken is another one where they sort of have the same evocative style of action. And that's the one, just coming from the inside, that's the style then that every fight choreographer and every stunt coordinator was going for. They weren't going for the Jackie Chan style--the Kung Fu stuff, as they called it. The shoe leather, as they called it: You're just getting to the kill. Just get to the kill, just get to the kill. And I think that that--you know, this is probably also just a byproduct again of the 24-hour news cycle where we have more realistic violent entertainment than we have fake violent entertainment at this point. Like, we're witnessing this stuff on a global scale constantly. And social media only makes it worse, because it's very reactive. That's why I recommend if anybody's trying to blunt their virtualizer, to just get off of these things and that'll help you. It helps you sleep at night. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I've talked about the fact that I love the show Daredevil. I thought it's incredibly funny, the series on the web. But, after a while, I stopped watching. I get depressed. The violence was so visceral in there for me--and maybe it was me, but it was too graphic. It was too easy for my neurons to fire there and be overly sympathetic. It just kind of brought me down. So, I just stopped in the middle of it, even though I found it remarkably entertaining--the nonviolent parts. But, the other thing I just want to ask is just--I don't know if you've thought about this, but I've seen this on Twitter a lot. Somebody will finish a series and they'll say, 'Can you recommend anything?' And so many of our most popular series on Netflix are gruesome. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. Yeah. Russ Roberts: They're not just, well, somebody's going to die or there's going to be some blood. They're gruesome is the way I would say. It's sort of a glorification of violence. What's going on there? Eric Jacobus: Somebody asked me the same thing on a recent podcast. I think that it's not so much glorification of violence as glorification of just mean violence. It's almost like--and I've canceled my-- Russ Roberts: Did you say mean, M-E-A-N? Eric Jacobus: Mean. M-E-A-N. If you go back and you do your classic villain, who has his final say--I think that in a good film, you can sort of steelman the villain's point--meaning that you could state his opinion very cogently, and you could kind of make a case for him. And that's what a good villain is, because then that makes a good hero. And it seems like a lot of these shows now, they want to otherize the villain, which is kind of interesting. They're otherizing the villain so that they do not have to even explain. It's almost like they don't even have a reason for what they do. I think it's very mean what they do. And, so-- Russ Roberts: The Joker franchise in the new Batman films has that feeling to me. I hated those movies for that reason. The first one, the one with--I can't remember the name of it now, that's sort of the origins of the Batman story with Christian Bale--I love that movie. It has some violence in it. But, the later ones I found so creepy and dark I couldn't enjoy them. Eric Jacobus: Yeah. I think that there's probably some element of social media culture seeping into narrative entertainment now, where we really don't want to hear out the opposition. Unfortunately, I think that that--I don't want to say it. That era might be over, Russ. I don't know. I don't want that to be true. But, man, any time I used to go on social media, it's like there was no way that you would hear out the opposition. I found myself doing the same thing and it was just utterly--you're taking your Oxford rules of debate and just throwing them out because it's all about hot takes and it's all about reactiveness. If you say anything about the other side, then that means you're x, y, z--you're all these bad things. Both sides of the debate do this; and it's just so frustrating because again, that's the mirroring mechanism because you also will mirror your enemy. That's what escalation to extremes does. And, social media has just figured out how to monetize that. Maybe that now is becoming the code of violence with movies where it's not about hearing out the villain and understanding where they come from. It's about just creating a cathartic, bloody experience. The idea is not to convert the audience: it's about to just assuage--it's just about sort of like getting them into the current culture to get them to agree with you as the producer. Because, that's what I find so compelling about something like a Charlie Chaplin or a Jackie Chan movie, is that the audience is converted at the end of it--if that makes sense. Russ Roberts: Well, I'm not sure how it applies to the Gold Rush Chaplin film. I'm not sure what you mean in the Chaplin context. I get the Jackie Chan but-- Eric Jacobus: Yeah, I think--what I mean by that is in the Chaplin context, there really is no villain. The fall guy is the hero. Russ Roberts: That's true. Yeah. That's true. Eric Jacobus: That's what great comedy is, is that when--and it's the same with Jackie Chan, a lot of the time, too. He has villains, but I think the great comedians would make themselves the fall guy. And, comedy expels the outsider, which is why the court jester was always--he has a permanent position as an outsider that you can expel, and he's paid very well for it. Russ Roberts: Interesting. Eric Jacobus: But, in the case of Jackie Chan and Charlie Chaplin, well, the hero gets expelled; but, by virtue of him being the hero, you're laughing at him. You're also understanding what it's like to be laughed at. Russ Roberts: Yeah. This is definitely some empathy there. And I shouldn't finish any conversation about mirror neurons without mentioning that there are some papers that we'll link to that talk about the connection of mirror neurons to Adam Smith's work and The Theory of Moral Sentiments and the empathy that Smith argued--that Smith really understood this long before we had any of the neuroscience correct in the early 1990s. |

| 1:17:49 | Russ Roberts: But, let's finish with your work. I want you to talk a little bit more about it before we finish. Besides a hit--like the Bourne Identity that you said, 'Wow, I want to do that'--how else has the have these theories of violence that we've been talking about in mirror neurons affected your work, if at all? Or is it just that you're reflecting on it in these essays? Eric Jacobus: I think that--well, it's sort of made me want to do comedy more than ever, because I think that comedy is in high demand right now, but it's extremely difficult to do a physical sort of Chaplin-style comedy in the studio system. It's made me want to do that more than ever. It's also made me think more about--you were talking earlier about almost like the memetic profile of someone like Muhammad Ali, who might have been specially gifted in his ability to see certain things and to mimic in a certain way. It's made me think a lot about all autism. Tyler Cowen's book, Create Your Own Economy, the chapter on autism, which is fantastic. I'll never--that really kind of kickstarted this, too. And, the idea being that-- Russ Roberts: What does this have to do with autism? Eric Jacobus: Well, if autism--as I understand it, because they keep on trying to diagnose autism with all kinds of new classifications. They don't seem to want to settle on a theory. And, I don't know if I'm on spectrum, Russ. When I talk about it, people with autism tend to respond positively. So, I seem to be able to understand this: that, autism does not have an issue with mirroring and copying people. There is no malfunction within the mirror-neuron system. There's no malfunction within the motor system with autism. Instead, you have a highly concentrated domain of expertise of mimicry. And it seems as though, in the extreme case of autism, that when you specialize in one domain--say, for example, there's a blind piano player. I should get his name. I keep citing him. He's a blind piano player who is autistic. And he has pitch-perfect piano playing. He can hear a four-minute-long song and then mimic it. So, when you have that kind of mimicry ability, how could you say then that autism is a mirror-neuron malfunction? It seems as though autism might--it might be a mirror-neuron phenomenon where people with autism, they can dedicate their entire mirror-neuron virtualizer to one domain of expertise and perfect it. But, the issue is that: if that domain of expertise is counting crayons, how then do you get that person into a different domain? And, shifting that is incredibly hard. I think that that would be a very worthwhile field to study because, you know, as Tyler Cowen said: there's probably a lot more autism going on today; and I think that it's a developmental psychology--I think it's developmental and not genetic, so much. I think it has to do with globalization of intent loads and, you know, the ability to kind of parse that stuff out and hone in on single actors. But, that kind of focus could actually make autistic people, for example, very good at copying movement and motion capture, for example, if they were able to shift their domain of expertise to that. And so, maybe by studying [?] neurons more, we'll actually be able to understand autism better and treat it appropriately--which is that, you know, there are shortcomings to autism, for sure. There's the closing off of the sensory organs. They cover their eyes and their ears because they don't want the intents being loaded into their virtualizer because it's almost like it's overactive. But, then once you actually get them into a situation where they can utilize that, it's like they're better than anybody in the room--maybe anybody in the world--and they can monopolize on that. And, perhaps then you can expand their horizons into being able to virtualize other domains besides the one that they're so good at. I have hope for that. I don't know if it's going to come from our scientific community. I think that they might be afraid to make a theory out of this for fear of offending people perhaps, but that's been a major source of my study right now. Russ Roberts: It's really interesting. |