| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: November 25, 2019.] Russ Roberts: Today is November 25th, 2019, and before introducing today's guest, I want to encourage listeners to go to econtalk.org, econtalk.O-R-G, and in the upper left hand corner you'll find the link to our annual survey where you can vote for your favorite episodes of the year, tell us about yourself and your listening experience. |

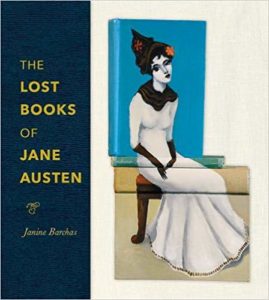

| 0:53 | Russ Roberts: And now for today's guest. My guest is author and professor Janine Barchas, the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor in English Literature at the University of Texas at Austin. Her latest book and the subject of today's conversation is The Lost Books of Jane Austen. Janine, welcome to EconTalk. Janine Barchas: Thank you very much. It's a pleasure to be here. Russ Roberts: This is our first episode on Jane Austen, pretty confident, of the 700-plus that we've done. Yeah, I know. It's hard to believe. And some listeners may be thinking, why are we talking about Jane Austen? I hope to reward your patience, listeners. And we have a really interesting episode today around Jane Austen herself, the phenomenon of Jane Austen, and a really beautiful book that you've written, Janine, The Lost Books of Jane Austen. It's beautiful physically. It's an aesthetically pleasing book that is not a great Kindle book. It would be okay to read it in the Kindle, but it's really beautiful to hold it in your hands. It's a lovely book. And it is a incredible detective story, a mystery that you've uncovered and explored in that book. Russ Roberts: So, let's get started by talking about Jane Austen herself. People probably heard of her. Tell us something about her. Janine Barchas: Okay. We could be here a long time if I tell you all my favorite things. Jane Austen, on the one hand, was simply born in 1775 and dies in 1817, writes six novels, lives a relatively quiet life, dies at the age of 41. And on the other hand, she is a phenomenon. And roughly around 200 years after her death, which is where we are now, the novels that she published starting in 1811 with Sense and Sensibility, and then Pride and Prejudice followed in 1813--those novels had their 200th anniversaries this last decade. And those anniversaries have shown, with the help of Hollywood, which kind of started in the 1990s with various movies, she's become the darling of Hollywood. She has become the classes that I teach that fill the most quickly. I now teach Jane Austen at 8:00 AM in the mornings in order not to cannibalize Milton or Shakespeare. And she, yeah, she's a phenomenon. She's entered pop culture in a way that Shakespeare did 200 years into his afterlife. And so, the Jane Austen Society of North America has 6,000 members that come together once a year. There are t-shirts, there is 'I Heart Mr. Darcy' underwear, there are celebrity ducks that--I mean, I can't believe that in 700 episodes, this is our first time talking about the industry that is Jane. Russ Roberts: It's a terrible oversight, but we're going to try to-- Janine Barchas: Obviously you're correcting that. Russ Roberts: Yeah. We're doing our best here today. I'm just shocked. I didn't realize that she was a published author for six years--only. That's extraordinary. Do we know what she died of at 41? Janine Barchas: We don't. There's lots of speculation. Imagine lots of academics hovered around her grave speculating about how she died. So, the speculation is an unsavory business. But yeah, she died of a liver ailment and she died too young, at 41, and yet she left an extraordinary legacy in those six novels. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Let's name the six just for listeners who aren't familiar with. Janine Barchas: Okay. So, we've got Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, and Persuasion as the novels that have all been turned into films. And then she left us with a few bits of manuscripts, Love and Friendship, an early work that has just turned into a movie by Whit Stillman, and Lady Susan, which he folded into that under that title, and The Watsons, and Sanditon, which has just been made. So even the smaller bits which we only have fragments are being turned into films and television adaptations. That's how desperate people are for a bit of Jane Austen. Russ Roberts: And I'd say, correct me if I'm wrong, alongside Shakespeare, she is perhaps the most well-known novelist in English. I guess you have Dickens for some competition maybe? Janine Barchas: Maybe, but-- Russ Roberts: But right now it's Jane Austen, I'd say. Janine Barchas: At the moment she's definitely the front runner and the poster child for the humanities. And yeah, she is, along with Will Shakespeare, the leading figure in literature. And yeah, it's a pleasure to be working on her, to be honest, and to see the author you're working on, and see her star rise this way. |

| 6:19 | Russ Roberts: So let's speculate a little bit. We could talk about this the whole time--I don't want to--but, why Jane? Why not George Eliot who wrote Middlemarch, a woman also-- Janine Barchas: Yes. George Eliot was great. Russ Roberts: writing under a pseudonym. Who else would be in the competition? We have Dickens, we have Trollope, for great British novelists--let's start there, pre-20th century. Who is her competition? And really nobody in her direct era that's still surviving reputationally. Janine Barchas: I mean, this is great question of course. It is like why do certain authors have t-shirts, and celebrity mugs, and bobbleheads, and why do others not have that? Sir Walter Scott, who was her direct contemporary, a great novelist in his own right, was deemed the sort of Shakespeare of the novel. And then a big monument was built in Edinburgh, and he was celebrated, and then his star simply dropped. And for reasons of, I don't know, length, interest, he is no longer the front runner, even though in Jane Austen's time, it looked like things would pan out very differently. And so, I don't think in terms of her celebrity that those of us who teach Jane Austen, or are read Jane Austen can be too complacent about her particular place in the canon at the moment, because those things do shift. But Shakespeare, after 200 years, was here to stay. And so, Austen seems, at her 200 year mark, to be very much a permanent fixture in the canon, and for good reason. They're absolutely great books. But there's something else besides, you're quite right, that other people write great books and yet, is it for reasons of length, is it for reasons that they bloom too early, is it that Austen was a bit of a sleeper during her own lifetime that makes us want to champion her more now as if we are the ones to discover her? I think that the magic of celebrity is mercurial and mysterious. Russ Roberts: I would just want to say one thing about Sir Walter Scott. When I was a boy, my father who was born in 1930 just presumed that Ivanhoe would one of my favorite books. I wanted to love it. I'm pretty sure I've read it, and I may have even read another Sir Walter Scott, I'm thinking; and I did love, I just have to get this on the record, because I had a, growing up I had a record, an LP [Long Play] of poetry and it was either--it was Alexander Scourby reading Lochinvar. O young Lochinvar is come out of the West,

Through all the wide Border his steed was the best; "Of all the wide" something "his steed was best." It's one of my favorite poems. I still love that poem. I've read it to my children. It's no "Ballad of East and West" by Kipling, for them, but I think they might know it a little bit. And he's gone. He is so gone. Reputationally. And one argument would be, and I'm going to bring us back to Jane, one argument would be that, well, really Ivanhoe is so dated. It's all about jousting and knights, and that's--kids want to read about Star Wars, and they want more livelier writing, and he's very archaic. And yet the other puzzle about Jane Austen is that the world that she inhabited, or her characters inhabited, is so alien to us, and so old fashioned in a negative way. And I've not read all of her books, I probably read three or four, of those, they often center around a young woman in poor financial situation, desperately needing to marry to preserve her station, her lifestyle. This is not just out of date for most modern readers: It's offensive. How do your students, and how do you react to that? Janine Barchas: I ask my students this question usually on the first day, sort of like, 'Why are you here? Why is this class full? Why does it have a waiting list?' And most of those students tend to be women, because Jane Austen, we can talk about that later, has become gendered in the way that she's marketed. So, 90% of my students in a big Jane Austen class, unless it's an undergraduate required class in which they're funneled in and then the distribution is half-half, it's often women. And I ask them point blank what you just said, which is, 'Why in the world are you here? These are books about a world in which women cannot inherit money, land especially; they cannot hold a job, they sit around waiting for Mr. Darcy. What in the world are you doing in this classroom? Why these books?' And hearing them defend Austen or their interest in her is very revealing. It isn't necessarily the literary treasure that I hope to offer them. It's usually that they say they long for a quiet world in which there are not six different technologies by which they can be rejected or what does--he Liked my Facebook post or my Instagram, and what does it all mean? But a world in which, as one student put it, he said, 'When I meet someone here in America, do I shake their hand? Do I hug them? Do I kiss them on the left cheek, or the right cheek, or both cheeks?' He said all of these things are possible. And, reading about a world in which there are strict rules and where every glance, every touch of the hand during a dance is meaningful, is a world in which for a moment, at least, I would like to visit. And-- Russ Roberts: Beautiful. Janine Barchas: Yeah, that was--well, I don't know how beautiful it is, but it is a recurring--different students express it differently, but that is their recurring sentiment. Russ Roberts: I hate to ask you this: Do you have a favorite? Janine Barchas: Oh, it depends on what day of the week it is. If it's Wednesday, it might be Emma, if it's another day it might be Pride and Prejudice. Pride and Prejudice is everyone's favorite, and so I usually never pick it. And Emma I find to be, in my rereading of it, always the most surprising. And so that probably is, yeah, that and Northanger Abbey are my favorites. Russ Roberts: And is there a movie or mini series version of one of the books that is your favorite? Janine Barchas: I would have to say, hands down, Clueless. Russ Roberts: I was going to mention Clueless. Yeah. Talk about Clueless for just a minute. It's not-- Janine Barchas: We can't linger on its cultural significance, but it is a movie that just translated the world of Jane Austen's Highbury and the very claustrophobic village life world in the novel Emma into high school cliques and high school Valley Speak. And it was enormously successful. And one of the things that always surprises me, because the movie is now 20 years old, is that it never advertised that, from the beginning, that it was an adaptation of Emma. So that, unlike Ten Things I Hate About You, which appeared at roughly the same time in the mid-1990s, a movie that signaled that it was based upon Shakespeare and it was redoing that in a high school setting, this is a high school version of Jane Austen that never recognizes its debt to Austen in its own marketing. And so everyone who watched it, many of my students say, 'Oh, it's my favorite movie,' because it's still a cult movie. And they watched it--clueless as it were--that it was based on Emma, and yet all the characters names, all the situations are, map on so beautifully, that part of the fun is to see how the original, if you know it well, is translated into this movie about an LA [Los Angeles] high school and the things that, the match-ups and mishaps that happened there. Russ Roberts: So I'm just going to put a vote in for Sense and Sensibility, which won best picture whenever it came out with Emma Thompson and Hugh Grant and the-- Janine Barchas: And Alan Rickman. Russ Roberts: Yes. That whole movie--it's a lovely movie, but it's worth sitting through just for the last five minutes, we're not going to talk about them, but for me I found that it's a moment of movie magic that it's just so well done. Janine Barchas: It is wonderfully well done. Yeah. Every part of it, I think, is terrific rather than just the last five minutes. |

| 15:48 | Russ Roberts: So let's talk about your book, The Lost Books of Jane Austen, which is part of the story of how Jane Austen came to be Jane Austen, which--tell us what you did, and what your enterprise was in that project. It's really quite unusual, quite beautiful. Janine Barchas: Thank you. I have to admit, I didn't set out to write a book about books--certainly not a book about shabby, cheap, schlocky editions of Jane Austen. It came about as a local curiosity where I found one copy from the Victorian era that had been published by Lever Soap Company. And I thought, how odd, and began scratching away at the history of this edition that was really kind of a white-labeled imprint that had been used in the end as a giveaway in the 1890s for soap wrappers to readers of a very working class status. And it had been part of a long list of books. Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility were both kind of soap editions. And, once I started looking into the history of this edition, I realized over time that not only had this particular edition not being recorded--and why would it? It was a giveaway. It wasn't a significant edition. It didn't end up in a major bibliography. It didn't end up in any library. But, at the same time I began to discover other editions also from the 19th century--especially the 19th century--that had never been recorded, that were all cheap editions, and that were at the bottom end of the book market. And because they were at the bottom end, and printed on bad paper, and probably included some misprints, they didn't count. And I began to collect them, and count them, and found a number of collectors who were interested in 19th century publishing, and 19th century publishers' bindings, or who had been interested in Austen for many, many decades and had acquired along the way various quirky editions. And putting all of those collections together, and doing a lot of unconventional eBay hunting for various flotsam and floatsam of book editions or bookish editions of Jane Austen that had been neglected, I discovered a whole inventory of works that hadn't been accounted for. And these works were all cheap, and it was their cheapness that seemed to have been offensive to those who were collecting, and recording, and studying Jane Austen. Russ Roberts: And some of them--many of them, I think--were railroad editions. Talk about that whole industry and how that came about. Janine Barchas: So, Jane Austen was, as I said, a sort of a bit of a sleeper during her lifetime. And then in 1833, so about 15 years after her death, a man named Richard Bentley, an enterprising publisher, decided to reprint a bunch of novels. He approached the Austen family, got the right to reprint her six novels. And so, in 1833 he is now[?] or he's treated as the Prince Charming, if you will, of the sleeping beauty story that is Jane Austen's slumbering reputation that gets reawakened in 1833 in these editions that cost six shillings, which was a huge drop in price compared to a first edition. Janine Barchas: But, Bentley's activities created these railroad editions--these other publishers that began printing at a much lower price point, one shilling, two shillings; and selling these books at railway stations, depots, bookstalls--in venues that were not as elevated as where Bentley was selling his wares, and create an entirely new market. Because you've got, I don't know if it's a perfect storm or you've got these perfect elements that all influence book prices and make them drop in the middle of the 19th century--pulp paper, stereotype printing, the steam press, and of course the steam engine of trains, and the new distribution networks that trains make possible for books. Everything lowers price along with cloth covers which become a standard in the 1830s as well. Russ Roberts: So here we have people all of a sudden having access to transportation. The WiFi on those trains wasn't so good. Janine Barchas: No, it really wasn't. Russ Roberts: So they look for something to do; and what they did is they stood around in the train station, was, there was a bookseller for this long journey who offered them a book that was often, I think you said tuppence or thruppence, a word I'd never heard before. I didn't know there was a thruppence. Janine Barchas: Yeah. Three pennies is a thruppence. Russ Roberts: And, I don't know what that amount would translate to in terms of an hourly wage of a worker at the day, but it's a small amount. Janine Barchas: Yeah. So that if you're comparing this elite guy named Bentley and his six-shilling editions that are high middle-class and genteel at six shillings, if you're dealing with an unskilled worker who is earning 10 or 12 shillings a week, that's not affordable. And so, this new category of books at railroads did to give people kind of an ability to binge-watch, an ability to buy, binge-read the kinds of books that had been part-published at the lower price point in serials and magazines. But binge reading was for toffs, for the elite, for people who could buy a whole book. And suddenly working people could buy an entire book for a shilling or half a shilling. And then in the 1890s it dropped even to three pennies, and two pennies, and one penny. And suddenly you have Austen being binge-read by everyone. And that phenomenon of her being read by coal miners, and school children, and ordinary working people is not something we usually have accounted for in our reception-histories of Austen, simply because we've been looking at the wrong books. Russ Roberts: Was she serialized originally? Janine Barchas: No, she was not. She published in three volumes at a time. So these were three-decker novels, the early version of that. And so they were quite expensive. Russ Roberts: What does that mean? What do you mean, a three-decker novel? Janine Barchas: Meaning that novels--and no one knows exactly why this phenomenon began: Was it libraries that could that liked books in parts, three large parts for a long novel so that three lenders could borrow at the same time; or did the fact that novels were suddenly being published in three volumes at a time? Even something that's a glorified short story like Mary Shelley's Frankenstein was published in three volumes. A lot of wide margins in the case of Frankenstei, because that was the convention: that a novel, that genre, was inhabiting three volumes at a time. I mean, there are some exceptions, people who are very long-winded, Frances Burney, Samuel Richardson: they don't fit into three volumes. But yeah, the three-volume novel became a phenomenon, and Austen was sort of at the forefront of that. But that also made novels very expensive items until cheap paper comes along mid-century, and cheaper versions. Russ Roberts: So just to speculate, I think of Dickens--Dickens was serialized. So if you were a Dickens reader, you read a chapter at a time in a magazine that later got put into a book. Presumably some of the technological changes you talked about that made those railroad additions possible made magazines possible and affordable, which led to the potential for serialization that didn't exist in Jane's time. But that's just interesting. |

| 24:42 | Russ Roberts: But the point is, is that scholars looked at fancy, leather-bound additions of books to look at how a author's reputation might rise and fall. What you've done for Jane Austen is tried to find as many of these less expensive editions. There's zillions of them. And what's interesting, of course, is that most of them should have been thrown away. Most of them were. They fell apart, they were pulped for a variety of reasons. But you found enough. Can you give a say of how many you dug up? Janine Barchas: This project's been going on, sort of slumbering in the background of other things for about 10 years. And then I found, a few years in, people who'd been collecting for decades, for four decades each. And so altogether we found, yeah, hundreds of books that were not recorded, many of which are pictured in the photographs in my book. Russ Roberts: With lots of changes in cover style and design. It's really fun. A lot of them are books that are part of my youth, not Jane Austen's versions, but again, Kipling or other British authors who get reissued at various times. So, it's very nostalgic for me to read your book. The other thing you did, though, which I think is extremely interesting, is that you did as much digging as you could with a number of these editions because people put their names in them and you tracked them down. So, tell us about some of that work and what you discovered about her readership, as a result. Janine Barchas: It turns out that even cheap books for this new category of working class reader were valuable commodities and proud commodities--sort of that sense of the emancipatory power of literature that Jonathan Rose talks about for the working classes. And so, many--the cheaper the book almost, that I discovered, the more likely it was to have a signature in it. And because now we have the magic of the internet, and ancestry.com, and all sorts of databases, the cost of researching the provenance history, the ownership history of a particular book is now so low that a few minutes can tell you whether or not you can triangulate this name. Is it unusual enough? If it's a Jane Smith, I'm very unlikely to find her. But if it's an unusual name, and it has a location in it, and then of course there's the date of the book, and when it was published, if you can use those to triangulate, then, yeah--I found many of these people whose books were suddenly on my desk or in someone's private collection here. And their stories made the research behind this book no longer academic, if you see what I mean. It made them those stories very personal. And at the suggestion of the editor at Johns Hopkins, I began to sort of develop them as separate pieces, as pieces between the chapters that deal with larger issues, so as to be able to kind of see a specific reader and how they had owned a copy, and what had happened to them. Because we always talk about 19th century readers or 20th century readers in this ghostly unnamed fashion. And suddenly here were real readers with real names, who had real lives, and some of those lives were pretty gritty. |

| 28:19 | Russ Roberts: Tell us about that one that you particularly found interesting. Janine Barchas: The one that I save for last in the book that I found the most touching, as in I sobbed, was a copy of Northanger Abbey that I found drifting around on eBay for a few dollars, that was signed, I made out, as an attendance price. Many of these books were, as you indicate, you recognize them. The books were folded into juvenile series for kids. So, Austen was also a kiddie read during the late Victorian and early 20th century periods. And I found a copy that was really pretty, I thought, of Northanger Abbey, made out to a young woman named Annie Monroe as an attendance prize in a school in Scotland in 1911. And the opposite page had been made over to another Monroe, Florence Monroe, and the full address for Market Street for Scotland of the home of Annie and Florence Monroe was given. So I was able to research these two girls and discover that they lived with four other siblings. There were six children and two parents, and they lived in a small place. And in the end, I discovered--you know, I thought it was so fun, and children reading. I was wrong. I discovered that Annie, six months later after receiving her book prize had died of diptheria because the whole neighborhood had had a diptheria outbreak, and the Monroe's lost two of their daughters. And I was devastated that this book, this trophy that had been so important to her, she had made it out in this shaky handwriting to her sister maybe when she was ill, I don't know, that that was what was left of this actual reader's life. And that these books told stories--stories about real people. Even the book collector who was helping me, she said, 'These are no longer books. They now all have names because of the people who once owned them.' Russ Roberts: Yeah. It's a bit of 19th century and early 20th century anthropology that you're, of course, doing there. And I think about my own books, which I have a huge emotional attachment to--I've referenced this recently--that I assumed I'd pass them on to my children. I'm not sure my children want them. I don't want my father's books, which, it makes me sad. He has a few thousand that he assumed I would probably want, or my siblings, and we want a couple maybe. But--and those inscriptions have a poignance about them now because they'll end up--any of those books just end up, it's not really, I don't know if it's sad, maybe it's something not sad, right? It's something really beautiful about it. They still get to be enjoyed, most of them. They survive and someone else gets to read them, so maybe it's not sad at all. Janine Barchas: Maybe not. I mean, these books are not as fragile as they've been deemed to be, in spite of their, even the ones printed on bad paper. They continue to last and continue to give testimonies. I think what's sadder is to think how if you're reading a book on a Kindle, how are you going to pass that-- Russ Roberts: Oh, yeah-- Janine Barchas: to the next generation? So that it's--yeah: these trophies do speak to people even outside of a family. Russ Roberts: Do you own a Kindle? Janine Barchas: I do not. Russ Roberts: Okay. Do you ever read a book on a electronic device? Janine Barchas: I told my students that there's 70%--seven-zero--less retention if you read it on the screen. And I would like to remember the stuff that I read if I'm going to read it. So, no, I'm pretty much of a Luddite. I like the paper products. Russ Roberts: I think it's 70.4. Janine Barchas: Oh, really? Russ Roberts: That's a joke for my listeners. The point-4 it makes it more convincing, it makes it sound more scientific. I doubt it's 70 either, but it might be less. There might be something less that's retained through a electronic screen. So, I'll concede that. |

| 32:52 | Russ Roberts: Is there a difference between her reputation, Jane Austen's reputation, in America versus England at this time? Janine Barchas: You mean today? Russ Roberts: Yeah, today. Janine Barchas: Um, I mean, I think that the English probably feel a sense of ownership that our accents deny us over Jane Austen. But no--I think that the only way I can measure that is that the Jane Austen societies in England and in America are different in kind in the events they hold and the way they celebrate their author. Their affections are clearly equally strong and their interpretations, and their use of Jane Austen is very similar. But their behavior at conferences--and, you know, the Americans, they tend to dress up, and they tend to-- Russ Roberts: Dress up meaning? Janine Barchas: Meaning dress up in Regency clothing and enact balls. And kind of, there is a yearly Bath Festival in the city of Bath in England that has that element to it. But on the whole, conferences are, in America tend to be a little bit more jubilant. And yeah, tend to celebrate the pop culture element of Austen maybe more than the Brits. Russ Roberts: That's so nice to us, because that makes them feel superior to us, which maybe they enjoy. Russ Roberts: You say in an essay, and you maybe say in the book as well, you say 'Cheap books help make authors canonical.' Thinking back to Chuck Klosterman's episode on EconTalk, "But What If We're Wrong," he speculates in there as to who would be the great iconic rock and roll figure 100, 200 years from now. And his view, if I remember correctly, is that that question is going to usually be determined by some set of obscure academics writing scholarly work on something that wasn't scholarly at all. And so, I want you to defend your claim about Jane Austen: That her cheap books, that her editions for the masses, made her a canonical figure, part of the literary canon rather than the arcane, abstruse, opaque scholarly work of people in the Academy. Janine Barchas: Okay, fair enough. Academics read editions and people read books. And I think that if Jane Austen had only existed, and it is a hypothetical, and we all hate hypotheticals--if Jane Austen had only continued to exist in those first editions, which were printed in runs as small as 500 for some of the novels and as large as 2000 for Emma, that's not enough of a reach. She had to be reprinted. And Bentley's reach for all of the academics that champion him is also not great enough. There's no way for me to prove this hypothetical, but I believe that the books that we've erased from history, the editions in which ordinary people encountered her, are the ones that kind of built her reputation from the ground up. And that canonicity is not, I think, the rarefied thing that a Henry James-style elite might make it out to be. Henry James famously in around 1905 sneered at all the different proliferations of Jane Austen in what, I think, he termed 'every kind of tasteful cover.' In other words, he saw Jane Austen everywhere, and lamented her being marketed in this kind of cheesy, schlocky way. And I think we owe her celebrity to that exactly, that kind of schlock. Russ Roberts: Mark Twain was not a fan. Janine Barchas: No, he was not. Russ Roberts: Do we know why? Janine Barchas: I think that the green-eyed monster also played a role in Mark Twain's approach to Austen, whom he said of, I think it was a library on a ship, that it had no Jane Austen in it, and that is what made it a great library. He started snarking only in the mid-1890s when he has this mean thing that he says about, 'Every time I do read Jane Austen I want to dig her up and hit her over the head with her own shinbone.' Very, very unpleasant thing to say. But, why would you say it unless you're truly bothered as a fellow novelist by the proliferation of an author who is so celebrated and so touted with all these cheap editions everywhere? Even he owned a couple of Jane Austen cheap editions and must have kind of seen that as a phenomenon and apparently resented it. Russ Roberts: By the green-eyed monster, you mean envy, I assume. Janine Barchas: I do indeed. |

| 38:28 | Russ Roberts: Okay. I want to push you out of your comfort zone a little bit. I want to talk about Trollope and Dickens. So, I'm a big Dickens fan. I've read a lot of his books. We don't see eye to eye on political economy, but he's an incredible storyteller. He's incredibly funny. And I think a case could be made that Anthony Trollope is a better writer. So, one question would be--here's a controlled case where--both prolific, incredibly amazing number of words produced in their lifetimes. I'm going to suggest--I'm going to try to be rational about it, which is probably wrong. But Trollope is--he wrote about somewhat obscure things, things related to the Church and British politics. You could argue then, Dickens is more accessible. But I suspect there were reasons that Dickens just got lucky. And I suspect that the ease with which people have made modern versions of his work--and I remember the classic comic, I was probably seven years old, of Oliver Twist or whatever it was that I read--that the movies that were made, that that is part of the story as well in terms of why Dickens is still world famous and Trollope is so obscure. Janine Barchas: Yeah. I mean, you're searching for an answer in plot. And, I suppose that in comparing them to Austen I would look for an economic reason as well, which is that they are both, as you point out, very prolific in their words, and they are not men of short novels. And these longer novels just don't reprint cheaply as well. And so, Austen benefited from not only being present at every kind of innovation in the history of the book as starting in the 1830s. She's reprinted on stereotype plates, and reprinted in books that no longer need to be in leather, and etc., etc. But she's the right size. Russ Roberts: I was actually asking a narrower question, which is out of your comfort zone, you, Janine, is that the way you say it, Janine? Ja[long a]-nine? Is that the correct pronunciation? By the way-- Russ Roberts: who's somebody whose interested in Austen. I was asking you to speculate about why Trollope is forgotten and why Dickens is still doing okay. Any thoughts on that? Janine Barchas: Yeah, I mean, I think Dickens is just simply livelier in his upholstered descriptions of everything-- Russ Roberts: fair enough-- Janine Barchas: animate the page in a way that--I'm afraid I'm not a Trollope fan so I don't share that conundrum. Russ Roberts: Okay. Fair enough. |

| 41:27 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk a little bit about Shakespeare. You are part of putting together an exhibit here in Washington, D.C., where I am right now, on, I love the title, it's called "Will and Jane." It was about Shakespeare and Jane Austen. Why were they paired? It was at the Folger Library, correct? Janine Barchas: Yes. It was at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Russ Roberts: So that's a Shakespeare place. How did Jane come to worm her way into that apple? Janine Barchas: That's a nice way of putting it. Russ Roberts: Sorry about that. It's just a cheap shot. Janine Barchas: Yeah. No. It was a very unusual year as well. That happened in 2016. Will Shakespeare was celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death and the 400th year of his afterlife. And I happened to be at a dinner with the head of the Folger Shakespeare Library. I happened to be seated next to him. So this is what happens when academics chat; and I was bragging that Jane Austen was giving Will Shakespeare a run for his money, and The Folger better do their best to try and lift their game a bit. And as we were sort of jousting verbally back and forth about Will and Jane, we seized upon the idea of what if we did a show together: wouldn't that be a blockbuster? And that's how come Jane Austen was let into the building that is the rarefied shrine, that is the Folger Shakespeare Library, dedicated entirely to all things Shakespeare. This was the first show in which Shakespeare had ever been double-billed with someone else. And Jane Austen got that honor. And more people showed up for that particular exhibition at the Folger than any other exhibition they had ever had. And so I think two plus two make more than four when it comes to that kind of celebrity and that kind of synergy between two very different literary creatures who have both drifted to the top. Russ Roberts: What was displayed at that exhibit? Right--the standard-- Janine Barchas: You mean aside from the shirt? Russ Roberts: Well, talk about the shirt. Yeah. Go ahead. Janine Barchas: So the shirt was the best rental ever. When I refer to The Shirt with capital letters, I am referring of course to the chemise worn by Colin Firth when he dipped into the pond at Pemberley. That was in 1995 Pride and Prejudice for television, written by the brilliant Andrew Davis. And that was a sensation in 1995, so much so that that's become this kind of strange focal point for the celebrity of Austen. And so when we said, 'Okay, well, we're putting Shakespeare celebrity at his 200 mark,' which in the 18th century, Shakespeare was suddenly propelled into the canon by the entrepreneurial activities of an actor named David Garrick, who created what we now know as kind of Stratford, the Disneyland of Shakespeare. And we said, 'Well, how can we compare that to Jane Austen now at the 200 mark?' So, 'Let's put them on equal footing, Shakespeare at 200, Jane Austen at 200: What does that look like?' And these public spectacles --there had been a Shakespeare gallery, and there were these Stratford events, etc. that had occurred in the 18th century, mapped onto the celebrity of Austen today. And so we were putting--you asked what was in the exhibition--we were essentially putting materials that were at least 200 years old that had been part of the 18th century celebrations of Shakespeare that were in The Folger's collections, and put them next to very modern materials. And that juxtaposition of high and low, and museum materials, and stuff we pulled from eBay--that irreverence is what, I think, animated the show and made it very loud in the gallery. People took 'shirties,' as they called them--photographs from standing behind the shirt in the case, photographing themselves. They dressed up again. They were--I think it was not the hushed museum experience that is the usual experience at The Folger when you're visiting a first folio of Shakespeare, but it was a different kind of almost theatrical celebratory festival of things that involved both Will and Jane. |

| 46:23 | Russ Roberts: And you have a very amusing satirical essay, which we'll post, where you claim, tongue-in-cheek, that obviously Jane Austen didn't write the books that are attributed to her. And, part of that was riffing on Shakespeare's reputation, which many people have argued--I think mainly just to get tenure--but, many people have argued that--or to sell books--Shakespeare didn't write the plays that are attributed to him. And my joke is, 'No, they're written by someone else with the same name.' But no, actually the claim is they're actually written by someone else yet with a different name, whether it was Christopher Marlowe or the-- Janine Barchas: Earl of Oxford. Russ Roberts: Earl of Oxford. Yeah. So, that's a lovely industry of fun publication and articles. But, I think the point underlying those articles and the point of your humorous piece, which I think is actually quite important, is that a lot of people have claimed, 'Well, of course they couldn't have written those books. Of course Shakespeare couldn't have written his plays, because he didn't know enough about the court,' or 'He didn't know enough about warfare,' or 'He didn't know enough about the monarchy,' or 'He didn't know enough about human beings.' Fill in the blank. And, your point was that you can say the same thing about Jane Austen, and yet somehow she managed it. And we're pretty sure she wrote those. Janine Barchas: Yeah. I mean, it is a fun game. The litmus test of celebrity has to be denial. And, in Austen's case too, this idea that sometimes people revert to biography for everything, to read a novel that is a proud achievement of the imagination, and to deny an author their talents by saying, 'Oh, this person writes about--.' You don't see that happening to Tolkien, that somehow he, its being insisted upon that his biography match his works. So, too, with Austen. Just because she was never married doesn't mean she didn't write the greatest love stories ever written. And that kind of denial of the human imagination I found offensive, and also at the same time the food for a column. Russ Roberts: Yeah. And, well, to be honest, in a way it's a compliment, right? Russ Roberts: To presume that this could never have been written obviously is to say-- Janine Barchas: Yeah. Because, 'She's so great, she couldn't possibly have done it.' Russ Roberts: Yeah. Like you say: The human imagination is a beautiful thing. |

| 49:01 | Russ Roberts: One of my followers on Twitter, Josh Dalton, asks, quote, "I'd love to hear her opinion on what Jane herself would think of the cinematic televisual adaptations of her works. Austen prized the rational and satirical yet adaptations are often gooily romantic. Would she thus be disappointed or appreciate the exposure and/or money?" Janine Barchas: I agree that some of the adaptations are worthy of a dentist in how unbelievably tooth-achie sweet they are. And I think that Austen's best work in all of her novels, in spite of often being quoted out of context in this kind of sincere way, she is a satirist, and she is a humorist. And she--she's funny, dammit. And that is what makes her works appealing and lively. And some of these gooey, as your listener says, adaptations seem more reductive. And so, yeah, as with the column you were quoting earlier about "Jane Austen is a fraud," that was published on the anniversary, the 200th anniversary of her death. And I thought that that was a better homage, to make fun, than to say how great she was, precisely because I, too, think that the gooey isn't always get at the point. Russ Roberts: But what would she have thought of them? Obviously she couldn't imagine them--its rather extraordinary. Janine Barchas: She couldn't imagine them, but at the same time, I mean, of course she would have been thrilled to be the center of so great a universe. I mean, she had little account books in which she took note of how much money she earned with every book. She had little lists of what other people said about her works. Mansfield Park includes a list where she even writes down what her mother thought, like 'Mother thought Fannie insipid but liked Mrs. Norris.' She wrote down every little bit. I think she would have been on Instagram and Facebook checking her Likes on a daily basis in order to kind of assess how she was doing and how her stock was rising and falling. Russ Roberts: You're so cruel. Janine Barchas: No! Good for her, I say. Good for her. Russ Roberts: You go, girl. |

| 51:43 | Russ Roberts: One of the interesting things I've been thinking about lately in terms of data and knowledge is this question of how we understand the world and where we get our knowledge from. And I complain that too many times I think people assume that the only things that count as knowledge are those things that can be quantified. And one of the topics came up in recent is whether one should have children. You could also ask whether you should get married. And, many of the people I was arguing with said, 'Well, we could do a poll. We could do a survey. We could find out something about whether people who did get married or did have children whether they're happy relative those who aren't.' I thought that was a little bit--I suggested that would be unproductive. Not to go into that now, but one of the things I suggested as an alternative would be to read a book--a novel. That is another way that we come to understand the world around us for making decisions like that. In fact, I could argue that fiction is a much better way to understand whether marriage, or children, or other decisions we make in life will make us happy and how we ought to think about them. What do you think of that? Janine Barchas: I think you're preaching to the converted. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Oh, boy. Janine Barchas: I'm a literature professor, and I teach books because I think that they matter. And I teach specifically the history of the novel starting in the 18th century, because I think that that particular genre, that literary creature that is the novel gives us stories that map onto our lives in ways that have that legacy and that had those dividends that you're talking about of knowledge and the human condition. So, yeah, I'm afraid I already drunk that Kool-Aid. Russ Roberts: So, I cried at the end of Sense and Sensibility-- Janine Barchas: Good for you-- Russ Roberts: the first time I saw it. Probably the second time I saw it, too. Janine Barchas: Oh--you saw it, meaning not when you read it? Russ Roberts: No, I don't remember reading. I have read it. I'm pretty confident I've read it. But in the movie version I cried. Janine Barchas: And then you were referring to Emma Thompson's brilliant screen play. Russ Roberts: Correct. Correct. But--did she write the screenplay? Janine Barchas: Yeah, she wrote the screenplay. And starred in the film. Russ Roberts: But it's directed, I think, I want to say by--is it Ang Lee who directed it? Is that right? Not sure. Janine Barchas: Yeah. That is correct. Russ Roberts: Okay. Janine Barchas: Ang Lee directed it. Russ Roberts: So, those are fictional people, made up folks. Not real, out of the imagination. The gray matter of a woman who died in 1817. And yet 200 years later I'm sobbing, that happened to be--well, I won't say how I was sobbing, but I was moved deeply by it. They're fictional people, though. You sobbed, you said, when you read about poor Annie Monroe, died diptheria six months after winning an attendance prize. Why does fiction do that to us? Is that not weird? Does that ever strike you as weird? Why do I cry over people who are not alive? Why do I not say, 'Well, there's nothing to be sad about. You are happy. These are just, they're just figments.' Janine Barchas: But that is--they are portals to empathy. I think it is a good sign of your humanity, Russ, that you cried in watching the--you know, it's a brilliant film, and Ang Lee and Emma Thompson did a fantastic job. And the ending of that film is not the same exactly as the ending of the book. But I think that you're describing our ability as human beings to empathize, and the fact that we don't have to live every experience ourselves. God forbid that we should have to experience war and hunger in order to empathize with those who are in the midst of that. And literature helps us to do that. |

| 55:34 | Russ Roberts: So let's dip into that Kool-Aid a little bit more, the humanities Kool-Aid. STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics] is on the rise. Humanities majors are down. Historically, professorships are down. I happen to be a staunch defender of the humanities. I have a son who is majoring in philosophy, and when people say, 'Well, what's that good for?' I always say, 'Well, thinking. And thinking is useful.' But let's hear your defense. Why take a class in Jane Austen? Is it just for the entertainment value of learning about--I mean, it doesn't have to be productive. It doesn't have to raise your salary. There are a lot of reasons that are good reasons for doing things that aren't related to income. But, what would you say in defense of English Literature and studying it at the university level? Janine Barchas: I mean, I think you're on the right track that, in the world of kind of a STEM-propelled utility function education we're losing sight of the thinking that always has to happen. I think that the students who--and I don't just preach to English majors in my classes. In fact, the classes that I love to teach are the ones that have engineers in them, and nursing students, and people who want to do other things with their lives other than be teachers, or go to graduate school. The way to think about a college education in America is to think about how different it is from the rest of the world. We have four years in which not just to develop a skillset that will lead to that utility function in that profession, but you have four whole years. Nowhere else in the world do you have four years in which to experience other worthy subjects. And I think that even if you don't become an English major, taking a class in Jane Austen teaches you to historicize, to be a human being, to think, to understand the importance of language, its precision. I could go on all day about the things that you can learn from one Jane Austen novel, let alone six. As I ask my students to rehearse on an almost daily basis, I tell them: We're not reading for plot. And then I say, 'No. No. I'm really serious.' And, 'Repeat after me and with feeling: We are not reading for plot.' And then the question was, well-- Russ Roberts: What are we reading for? Janine Barchas: what are we read reading for? And, we're reading in order to transport ourselves to another time, perhaps so that we don't repeat all the lessons learned from life in 1813, but can learn from these works. So I see them as portals into history as well as extraordinary examples of human literary achievement that, in a very efficient way, can teach us about humanity, and can make doctors better doctors by having read a work like Persuasion; and all this references to nursing that happened in that particular text, or aging. Literature helps us to be better at whatever it is that we do, I think. It's not--it's sort of the grease on many, many wheels. It's not something that needs to be necessarily studied for itself alone, but in combination with many other things. |

| 59:27 | Russ Roberts: Another question from a Twitter follower of mine, Laura Miller: She asked--she'd be really interested in the financial aspects of marriage in the late 18th century. Which points out another aspect of reading fiction, older fiction in particular--that it tells us something about how life was lived in a way that a Wikipedia entry does not. Do we know anything about the accuracy of Jane Austen's--her characters' concerns and anxiety and dreams, as to whether they captured a small part of the population of her day, a large part? What do we know about that? Janine Barchas: We know that you can put an extraordinary amount of interpretive pressure on all the details in her stories and begin to realize that she did her research. So that, when she references Mr. Bingley coming into town with £4,000 or £5,000 a year, it's because the kind of Navy bonds, the government bonds were at the time giving 4% or 5%. And that means that she calculated that he had inherited from his father, Mr. Bingley Senior, £100,000 pounds, and was therefore living off of that interest. This is a new kind of money. This is someone who is not landed wealth, but new wealth, moneyed wealth. And, all of those little details about heiresses who have so many thousands of pounds, and about how the distances traveled by characters between certain places--that is the kind of precision that you and I expect from a James Joyce, where people with stop watches, they're measuring the flow of the Liffey through Dublin between the chapters. And she is just like that. So I think that when it comes to the reliability of her stories, they can be relied upon by someone who was really there and who did her homework. And, the fact that all the economic details--the prices of things and those numbers--all add up in her stories means that, yeah, she was someone tracking the economic reality of her day, the reality of those women in those stories. Russ Roberts: What about social reality, the insecurity and fears, often, of her characters? I guess you could argue that there's a gothic horror aspect of her stories. I'd never thought about it in that way. Russ Roberts: Do we have a reason to think that was common, mainstream, everybody? Or was it just a particular niche? Janine Barchas: I think that, in terms of Austen kind of living on the edge of gentility herself as the daughter of a clergyman and the sister of brothers who were in the Navy and did very well there, and brothers who were part of the landed gentry, that, yeah, we're talking about--what?--10% of the population, max, in terms of that, who would have £4,000 or £5,000 a year and be in that class of people. But, in terms of her stories: I don't know if this answers your question. But one of the questions I invariably get after the first lecture, whatever the substance is, electron literary illusion, or about economics, or some detail where as a professor you use zoom in to a text, to a particular page, and you kind of unpack a paragraph or unpack a particular scene. Invariably at the end of that first lecture a student will raise their hand and will say, 'Okay, I understand what you said, but in Austen's time would people have noticed this?' And, in other words, I always get called out by my students as sort of like, 'Is this about you, Professor Barchas, and, you know, sort of the smarts we apply now? Or is this about those particular people and the suspicion that we as readers are smarter readers than Austen's original readers?' I mean, that's the kind of hubris that the Greeks write about. And it's the kind of hubris my students tend to inhabit. They think that people in, you know, 1811 couldn't possibly have tracked that literary illusion because they weren't in college now, or something; or they didn't have Twitter or Google at their disposal. Whereas the opposite is of course true. These books, because they were a relatively new genre still, and Austen is doing something daring in new with her particular stories, that close-knit zoom that is really about much larger issues than at first glance it seems--that readers would have paid unbelievably close attention to those £4,000 or £5,000 pounds, those £4,000 or £5,000 a year. And would've done the calculations. And would have been smirking along with her stories. And that historical distance gives us a false sense of hubris, when in fact it should enhance our humility before the text. |

| 1:05:03 | Russ Roberts: One thing I've noticed is that in many pop culture stories about the past, and they are, obviously, tend to take a cardboard approach, where women, for example, are oppressed by men 24/7 [24 hours a day, 7 days a week]. They have no authority, no autonomy. And of course to some extent, Jane Austen's books are a tribute to the way women used the limited power that they have. But they had some power, obviously, in her day. Do your students find that sometimes difficult, that they have a particular perception of the battle of the sexes from today's looking back that might have to change when they read Jane Austen? Janine Barchas: Yeah. I think that, of course, students, all of us tend to be anachronistic when we're looking at a work 200 years ago. And that time travel element, that reading something in historical context and understanding what the language meant at the time, and kind of modifying our own cartoonish, as you point out, expectations or sense of the past, yeah--that that is what a work of literature--I mean, it is what Shakespeare does, it is also what Austen does, and even Dickens at times can kind of modify our sense of, I don't know, it's almost historical superiority, isn't it?-- Russ Roberts: For sure. Janine Barchas: This sense of that: Yeah, that we know best. And so, we judge in a way that has kind of no historically responsible context. |

| 1:06:46 | Russ Roberts: So I'm going to share something with listeners I'm very confident I've never shared before. I had a great uncle, Henry C. Roberts. He had a little bit of fame in his lifetime. He wrote a book called The Prophecies of Nostradamus. I never met Henry, I'm sad to say. I tried to meet him once with my family. We were in Philadelphia where he owned a bookstore, but it was closed and we didn't see him, and long distance calls were expensive then. We didn't call ahead. And that was just the way it was then. But Henry had a heyday, my father tells me, where he appeared on talk shows in maybe the late 1950s, early 1960s, claiming to be a reincarnation of Nostradamus. And there was a period allegedly where he only spoke in Old French, which was--it must have been difficult for his friends and family. But I thought about Henry because your name is Janine, which sounds a lot like Jane, and somehow you live in Austin, Texas, slightly different spelling, but that could just be to throw us off. Does that--do you ever think about that? Russ Roberts: And I have to say, that's the most foolish question I've ever asked a guest, but I couldn't resist. Janine Barchas: It really is. And it shows that deep in your soul you are a punster at heart, and I'm not sure what to make of that. But, other than the fact that my publisher on the first book spelled the author as 'Jane' Barchas, and the fact that I have t-shirts that say Austen in Austin for my large electric classes, and that I currently made use of that pun in an exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center of their Jane Austen holdings that's called Austen in Austin that's on show until the 5th of January here with a lot of gobsmacking things: One makes use of the pun, Russ, but one does not necessarily believe in it in a faith sense. So that's my answer to that. Russ Roberts: Okay, good. I'm somewhat relieved. Janine Barchas: I'm not channeling Jane Austen, for God's sake, no. |

| 01:09:06 | Russ Roberts: If you are a listener to this episode, you've never read Jane Austen--which I suspect there are a few in that in my audience--where should they start? What is your--is there any advice you might give as to order or-- Janine Barchas: I think that-- Russ Roberts: first one if you're only going to read one? Janine Barchas: If you're only going to read one or if you're just going to start and see how it goes, I would suggest absolutely Pride and Prejudice. It will give you the greatest social currency out there if you've read that particular story. And it's also the one that starts with dialogue. It's her second one, and published in 1813, and it's almost as if she's worked out all the kinks. And the opening of that is so wonderful that in a large lecture class I usually act it out with students, because it's such an easy way in. Russ Roberts: My guest today has been Janine, Janine Barchas. Her book is The Lost Books of Jane Austen. Janine, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Janine Barchas: It's been a pleasure. Thank you. |

Author and professor Janine Barchas of the University of Texas talks about her book, The Lost Books of Jane Austen, with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. The conversation explores Austen's enduring reputation, how the cheap reprints of her work allowed that reputation to thrive, the links between Shakespeare and Austen, how Austen has thrived despite the old-fashioned nature of her content, Colin Firth's shirt, and the virtue of studying literature.

Author and professor Janine Barchas of the University of Texas talks about her book, The Lost Books of Jane Austen, with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. The conversation explores Austen's enduring reputation, how the cheap reprints of her work allowed that reputation to thrive, the links between Shakespeare and Austen, how Austen has thrived despite the old-fashioned nature of her content, Colin Firth's shirt, and the virtue of studying literature.

READER COMMENTS

Trent

Jan 20 2020 at 8:23pm

Very interesting discussion, and I, for one, didn’t mind the rambling question near the end about Janine (Jane) from Austin (Austen), TX.

Regarding your discussion of forgotten 19th century British authors who shouldn’t be forgotten, I’ll submit Wilkie Collins for consideration. His “The Woman In White” still reads as the first soap opera (like much of Dickens work, it was serialized, so it’s got ample suspense). And “Armandale” has one of the most complex, yet engaging, plots that still holds up. I’ve read at least a dozen of his books, and like Dickens and the other authors discussed, most of Collins’ plots also involve women lacking the legal rights of present-day times, fighting unscrupulous men who are trying to cheat them in various ways. To me, Collins is much more readable and enjoyable than Dickens.

Sarah Skwire

Jan 23 2020 at 1:33pm

Great call on Wilkie Collins, Trent! He’s much neglected, and undeservedly so. The Woman in White is unputdownable. You also might like Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Shuttle. While she’s best known for Little Lord Fauntleroy and The Secret Garden and other children’s fiction, she wrote some big potboilers for adults. The Shuttle focuses on women’s property rights issues, right at the moment when transatlantic crossings increased marriages between English aristocrats and the daughters of American industrialists and brought two different sets of expectations about women’s property rights into conflict. Stay tuned for an upcoming EconLog post on that!

Doug Iliff

Jan 20 2020 at 9:49pm

As for competition among British novelists— have the Brontë sisters lost their critical acclaim?

Luke J

Jan 21 2020 at 7:12pm

I too thought their absence of mention was notable: they share similar film, theater, pop culture fame, and are (today) closely associated in era and style. C Brontë criticized Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and some suggest Emily would have been a greater (whatever that means) writer had she lived longer (and presumably penned another Wuthering Heights.)

Missed opportunity in an otherwise enjoyable and emotional episode

John P.

Jan 21 2020 at 9:40am

I just would like to correct (or supplement) Prof. Barchas’s comment that women in Austen’s time could not inherit money or property. In the early 19th century, women could, and did, inherit money and property. The important difference from today (at the risk of oversimplifying) is that during the time a woman was married, her husband could act unilaterally for her with respect to all her personal property and with respect to the husband’s right to all the rents and profits from his wife’s land. The husband could also veto his wife’s dealings in her own property and land.

Philip Jollans

Jan 21 2020 at 1:22pm

If I may, I would like to describe why I think Jane Austen remains so popular.

Her books have the extraordinary quality, that you can read them again and again and continue to enjoy them. Knowing what happens does not detract from the enjoyment in the least.

If you have an audio book, when you get to the end, you can start listening at the beginning and enjoy it just as much the second, or third, or fourth time.

An on rereading a book, you will find details which are only apparent, if you know what happens later in the story. For example, somebody expresses a view which takes on a special meaning in relation to their actions later in the book. Or they behave in a manner, which makes more sense when you know what happens later.

Austen seems to have the complete story and the personality of every character in her head, before she writes the first word.

I hardly dare to make the comparison, but the only other books I know which have this quality, are the seven Harry Potter novels.

Val Larsen

Jan 23 2020 at 4:43am

The dynamic on Kindle books is the opposite of what you implied. Russ said his father is sorry that his descendants don’t want most of his beloved books. So they will be lost to the family when he passes away and his household is dissolved. Janine complained that one doesn’t have marginal notes in a Kindle book. But of course one does, and they can be preserved and passed on indefinitely, both the books and the comments in them. My children and I share a Kindle account. We have a family library. All my books will be passed on, along with all my many underlines and marginal comments. In principle, the family library can continue for generations. Perhaps my children and grandchildren won’t be interested in my books and underlines and comments, but a great grandchild will share some of my passions and take interest in his or her intellectual heritage as reflected in the history of family reading. That great grandchild is much more likely to have access to my digital library than he/she is to have access to my physical library.

Luke J

Jan 24 2020 at 3:45pm

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies by Seth Grahame-Smith was my gateway to Jane Austen. She is a clever writer, but a less-clever me needed more explicit prose to appreciate the original.

The novel, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, is good for a laugh. Skip the film.

Chase Eyster

Jan 26 2020 at 2:13pm

Today I jumped onto the treadmill for my much anticipated weekly run and economics primer with Dr. Roberts, and I was delighted to find the podcast topic was Jane Austen. I agree with Dr. Barchas and the host that instruction in the humanities should not be ignored in our current STEM-driven culture. Many thanks for the topic and the wonderful conversation!

Tim Konek

Jan 30 2020 at 11:29pm

What might happen if Russ finds out Keynes was a fan of Trollope…

I’ll Never Read Trollope Again, by Dave’s True Story

Comments are closed.