| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: June 18, 2018.]

Russ Roberts: Before we begin, I want to let listeners know we have redesigned the econtalk.org website. Please check it out. There's a new player; it has different speeds. There's a chance to rate each episode. The whole thing will look nicer on your phone. The formatting of the comments is beautiful, as are the Highlights. So, please check it out: econtalk.org. |

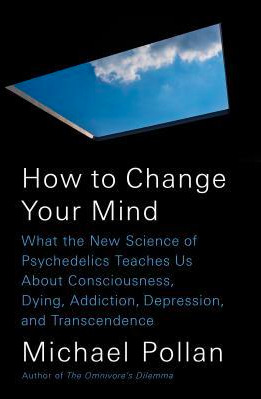

| 0:59 | Russ Roberts: Now for today's guest, journalist and author Michael Pollan. His latest book and the subject of today's conversation is How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence.... And I do want to let parents know--it should be obvious from the title of Michael's book or at least the subtitle--this conversation is going to deal with what are sometimes described as hallucinogenic drugs, in particular LSD [Lysergic acid diethylamide] and psilocybin. You may want to screen this episode before sharing with your kids. This book shook me up in all kinds of ways that I hope we'll cover in our conversation, Michael. One way it shook me up is I discovered that there was serious scientific exploration of psychedelic drugs in the 1950s and 1960s. Give us a sketch of what that research is looking at. Michael Pollan: Yeah. I was surprised, too, frankly. For most of us, I think the history of psychedelics begins in the 1960s, you know, with Timothy Leary and that whole scene. But I was surprised to learn that there was a very lively, productive area of research for more than 10 years before Timothy Leary ever tried psychedelics--which doesn't happen till 1960. The drugs are--well, LSD is invented, you can either say in the 1930s when it was synthesized, but it wasn't realized what it was till the 1940s. Albert Hofmann was a chemist at Sandoz, and he was looking for a new drug to treat women in childbirth, to staunch bleeding, I believe it was. He accidentally hits on this--he's working with ergotamine, which is this chemical that's produced by a fungus called ergot, which infects grain and actually has an interesting role to play in European history. But, he realizes by accidentally ingesting a tiny bit that he's got this powerful psycho-active substance. He has no idea what to do with it, however, or what it's good for, if anything. So, Sandoz does something really unusual. They essentially crowd source a 10-year or 15-year research program, offering LSD-25, as it was known, to any researcher or therapist who agrees to report back on what they learned. So, anybody with good stationery basically could get a lot of LSD, for free, if they were willing to report back. So, all through the 1950s you have this effort to define what it might be good for and apply it therapeutically. And, what they discover--and this happens by about the mid-1950s--is that it seems to be effective in treating addiction, especially alcoholism; depression, anxiety, obsession. A whole range of forms of mental illness. Although they also try it on schizophrenia with somewhat less success. But this is going on in England, in Canada, in the United States. And many people in the psychiatric community think that this might be a wonder drug. It also teaches us really interesting things about the mind. We did not really understand chemistry of the mind before LSD. And the fact that there were receptors and neurotransmitters--that whole area of research really was opened up by the study of LSD. So, it's this very important drug. It's legal, at this point. There's no stigma attached to it. And it looks like it's going to help us treat mental illness. Russ Roberts: And then what changes? Michael Pollan: The Sixties. Basically, in the 1960s the drug becomes very popular in the counterculture. Timothy Leary, who had been a scientist, kind of loses patience with science and is so excited about the possibilities of this drug--which, by the way, is an occupational hazard for just about anyone who studies it, this irrational exuberance--that he basically loses interest in treating individuals and decides he wants to treat the whole of society. Which, you know, we don't really have a paradigm for prescribing a new[?] drug-- Russ Roberts: It's ambitious-- Michael Pollan: Yes. With the exception of fluoride--that is one drug we apply to all of society. But he becomes an evangelist. But, he's not the only one. It isn't fair to blame him for all this. You know, on the West Coast, Ken Kesey, the writer, tries LSD--actually, on the government dime. He was dosed as part of a CIA [Central Intelligence Agency] research experiment in the early 1960s, and decides also that this is a very powerful tool that everybody needs to have. And he gives it out in these acid [N.B. 'acid' is slang for LSD--Econlib Ed.] tests in the Bay Area. And also, even before that, Cary Grant had given an interview about his very successful treatment, as he deemed it himself, very successful treatment with LSD in Los Angeles in the 1950s, and gives this interview where he's kind of raving about it. And that, too, is exciting public interest. So, basically, the drug is embraced by the counterculture. It's used pretty carelessly. People are taking it at parties and taking it at concerts, and without much thought. They are dosing one another without their knowledge--which seems to me an incredibly cruel thing to do. And, gradually what had been a great deal of support for psychedelics on the part of both the media and the psychiatric community turns into a reaction against it. A backlash. Or, a moral panic, even. And, you start hearing a lot of scare stories about people getting in trouble on the drugs: They are having psychotic episodes, they are jumping out of windows, they are staring at the sun till they go blind. Not all of this is true. A lot of it are really scare stories. And the Press turns against it. And, by 1965, you have this, you know, moral panic against LSD and psilocybin, that quickly results in their prohibition. Which is not complete until 1970. But in 1966 they are made illegal in California and some other states. And, the researchers basically get a little chicken about studying it. Even though they were getting good results and were very committed, I don't think they were willing to go up against this powerful public and government tide of opposition. And so gradually the research dries up. And, by the early 1970s, that's it. This promising avenue of research is choked off. Russ Roberts: And we both mentioned psilocybin. Explain what that is. Michael Pollan: Yeah. Psilocybin is the chemical in magic mushrooms. And this is a psychedelic that is kind of widely available. These mushrooms grow in many places. And, it was not known, though, in the West, until 1957. And that's when Gordon Wasson, who was an amateur mycologist and a banker, actually, at J.P. Morgan-- Russ Roberts: mushroom expert, a mycologist-- Michael Pollan: Mushroom expert. Yes. Goes to Oaxaca in Mexico. And he's heard rumors that there are mushroom cults that have survived in Mexico since the Spanish Conquest. Quite incredible. When the Spanish came to Mexico, they found the Aztecs and other native peoples using mushrooms as a sacrament. They called it Teonanacatl--Flesh of the Gods. And they regarded this as pagan. They felt very threatened by it, because it was, in some ways a superior sacrament to their own, since you didn't really need faith to make contact with God. You just--you could actually talk to him--with mushrooms. And so they crushed this religion. And, it went underground; and survived for 500 years, coming back to attention with this big, 15-page article in Life magazine, that Wasson writes in 1957. Russ Roberts: I should just mention, of course, to listeners, that many mushrooms are poisonous, will kill you. Do not go out into the woods eating mushrooms that you don't understand. And LSD is illegal. We do not encourage anyone doing anything illegal. And that's a disclaimer I think I'll--a similar one in the front of your book. But, carry on. Michael Pollan: Yeah. LSD is now illegal; and psilocybin is illegal also. However, they are--they can be used by researchers. And they are being used in research trials. |

| 9:40 | Russ Roberts: So, how did those trials come back, in scientific study? What changed after that scare in the Sixties, which I remember vividly as a teenager--that these were horrible drugs; they drove you crazy; and you shouldn't touch them. And that was very effective. Michael Pollan: It was. It scared a lot of people off them. I mean, there still was a counterculture where they were used. But, I was scared, certainly. I didn't mess around with them at that age. I believed the horror stories. But, there was always a group of people who were faithful to psychedelics and were convinced that they had value for society, whether as spiritual aids or as therapeutic aids, or as just a means of exploring consciousness, individually or as a species. And so, they kind of, you know, kept the fire burning. And, we had this hiatus of about 25 or 30 years, where no research takes place in the United States. And, beginning in the early 1990s, a group of people who consisted of some therapists and some activists--some people whose lives have been changed by psychedelics in positive ways--began organizing to see if they could perhaps re-start the research. There's a series of meetings that takes place at Esalen, which is a--to call it a conference center is to kind of trivialize it. But it's this gorgeous-- Russ Roberts: Heh, heh, heh. That's hilarious--but, yeah; it is a conference center. But, yeah. Michael Pollan: I guess, technically, it is. But it's a-- Russ Roberts: Retreat center. It's a-- Michael Pollan: Yeah. It's right on the coast of California in the Big Sur. It kind of leans out over the Pacific Ocean in this precarious way. And it's gorgeous. I've been there once. And, it has been a center of the Human Potential movement--you know, if the New Age and Human Potential Movement had a capital, that would be Esalen. And so, they start having this series of meetings there; and LSD therapy had been developed there, to some extent. And, they start figuring out how they might bring it back. And, I focus on a man named Bob Jesse in my narrative, who is a computer engineer. He had been at Oracle. He had some very meaningful psychedelic experiences in his 20s. And, he organizes a group of people-which, a range, from religious scholars to therapists to a former head of NIDA--the National Institute of Drug Abuse. And, they start, you know, coming up with some plans, of: What would you study? How would you go about it? Jesse has some money, and he raises some more money. And he, then, approaches some researchers, and is introduced to a man at Johns Hopkins, a very prestigious, well-regarded drug researcher named Roland Griffiths, who had been studying, you know, drugs of abuse for a long time. As it happened, Roland had had a powerful mystical experience of his own in his meditation practice. He was not using psychedelics, but he was a very serious meditator, and had been exposed to some ideas about consciousness that he couldn't explain through, you know, the usual scientific explanations. So, when Bob Jesse and Roland Griffiths meet, that's really the beginning, I think, of modern research. There's a few other things going on, too. But, there was a change of attitude at the FDA--the Food and Drug Administration. And, a new hire there, who happens to have been a former student of Roland Griffiths', says that he will henceforth look at proposals to study psychedelics as if it were any other drug. Leaving aside its history. Leaving aside its legal status. And so that kind of opens the door; and Bob Jesse and Roland Griffiths step through it. And they revive this science after this period of dormancy. And, really my book is the story of that renaissance. |

| 13:50 | Russ Roberts: Well, that's part of your book. The part I want to turn to--and it's fascinating. The book is, it's a great read. You're a great writer. But, the reason it's a fascinating book--if it were just that history, it would be a good book. But it's a great book, because it intersperses that history with your own experiences, which we'll talk about in a minute, along with a lot of, to me, fascinating questions about science, consciousness, materialism, and so on. One thing I think we need to make clear before we go any further is that, I think when most people, as I would have before I read your book--I mean, you say, 'Well, people are using LSD for therapy,' or to help people with addiction, or they lead to meaningful experiences--I think what people have the idea is that, the people who are evangelistic or evangelical about it are high "all the time." That, this is just--they are living in an "alternative world," like a perpetual drunken spree. But, what your book mainly highlights are experiences that people had, sometimes just once. And that many of the therapeutic applications of the drugs--for addiction, for fear of death--are just a one-time use. Which is just not just what I would have had in mind. And the second thing I think we have to make clear is what the experience is for many of these people that is often described as spiritual or religious, transcendent. Try to give us some flavor of how people report on this, and to why they become evangelical about it. Because, if you'd told me this before I read the book, I would have said, 'Well, sure. When people get drunk, they like to have other people drink with them.' Or, 'When people get high, it's fun; they want to share that experience.' But this is something really extraordinary that I had no idea about. Try to give the flavor of that. Michael Pollan: Yeah. It's not about being high. And, what is striking about these drugs-- Russ Roberts: and they are not addictive. That's another crazy thing that I wasn't prepared for, right? Michael Pollan: Yeah. A few things you should know about them. First: Yes. A single experience, or two, really is all we are talking about. And that experience can be so powerful that it really is transformative of people's outlooks. And even, to some extent, their personalities. The other thing it's important to understand is that you are not just taking a pill. You are having a guided experience. So, when we talk about psychedelic therapy, we really should be saying psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. So, the way it works in a therapeutic context--and this was a context really created way back in the 1950s--is that you are with a guide, or a therapist, the entire time. They take great pains to prepare you for the experience. Because, it can be very disruptive. And so, they tell you what to expect. They tell you what to do if you get into trouble, if you have a period of great anxiety or you see something really scary. A lot of it involves encouraging you to surrender to whatever happens. And that the so-called 'bad trip' is often what occurs when someone resists what they are feeling. Which might be a sensation of going crazy, or their ego dissolving, or, you know, that they are dying. They think they are dying. And the best advice is, 'Go with it. You go with it, it will turn into something more positive.' And then, the guide is with you the entire time. They don't say very much, but they are present and give you a sense of safety. Because, you are going to be in a very vulnerable situation. Your ego defenses will be disarmed completely. And so you have to feel safe, or you are going to feel very paranoid or anxious. And then, after the experience, which can go on for somewhere between 6 hours on psilocybin to 10 hours on LSD, after the experience they help you integrate it: make sense of what happened and see if you can't extract any lessons that you can apply to your life. So, this way of administering the drugs is very different than the image I think people have of recreational use of psychedelics. The other thing you should know is: You are wearing eyeshades during the whole experience. Which encourages you to go inside. It's a very internal journey. You are not just kind of grooving on the waves on the beach or the trees in the forest. You are really examining your life. And you are going into your mind, and into your body as happens in the case of many of the cancer patients. So, it's important to understand that. And that, you know, it doesn't necessarily work without the therapists. It is a package that we are talking about. Even though, you know, it doesn't happen without the chemicals. But, the other interesting point about this is that, you are really prescribing an experience to someone, not just a chemical. In other words, people can have a reaction and feel like they are hallucinating and all this kind of stuff; but it really is only if you have what is sometimes referred to as a mystical experience or an ego-dissolving experience. This sensation of your self merging into something larger. That, that appears, that experience appears to be the best predictor of a positive therapeutic outcome. And it doesn't always happen. It seems to happen in about two thirds of the people who have one of these guided journeys. |

| 19:21 | Russ Roberts: Well, I want to focus on those two thirds. Because, obviously, one of the themes of the book is that it's hard to put the experience into words. Michael Pollan: Yes. It's ineffable. Russ Roberts: Ineffable. One of my favorite words. But, do your best to give an idea of what's in that's 2/3rds of the experiences that go well, or somewhat, or whatever you would call 'well.' There's a certain set of common experiences, which is fascinating, actually, that people experience across the board. What are some of those common spiritual/transcendent experiences? Michael Pollan: Well, on a high-dose psychedelic journey, the most common thing is what I described earlier, which is this sense of your self dissolving. And that you are--that, you know, what your ego is doing in everyday life is kind of like patrolling the borders between you and other people, you and the natural world, subject and object. And this is a very important function. And it gives us, it helps reinforce this idea that we are distinct individuals with some kind of continuity over time. But, to realize, as the Buddhists have been teaching us for a long time, that perhaps that is an illusion; and that it can vanish or evaporate, is a very destabilizing experience. Which can be terrifying if you are not prepared for it and you resist it. But it can also be ecstatic. And, you know, this sense of merging into something larger is often filled with feelings of love, connection to nature. This sense of one-ness. What William James called 'unity of consciousness.' And it can be absolutely thrilling. And surprising. Because, I think most of assume we are identical to our egos, and that chattering voice in our head telling us what to do, criticizing us-- Russ Roberts: --That's me! Michael Pollan: That's me! And we're continuous with that. But, to, to realize that can go away, as it did in one of my journeys--and yet you survive, and that there is this other perspective that's very, um, disinterested, yet compassionate, not invested in any strong emotions, and is just kind of observing--this disembodied awareness--is actually a kind of liberating perspective. I don't know what it is. I don't know what generates it. Some people are convinced--Aldous Huxley was convinced--that that is the mind at large. Some kind of consciousness, field of consciousness that exists outside of the brain, that we can take part in. I tend to assume that any form of consciousness is generated by my brain. Call me old-fashioned. But that seems like a more parsimonious explanation. But many people don't. You know, there are very serious physicists and philosophers who think that, no, consciousness may be one of the building blocks of reality along with, you know, electromagnetism and gravity and light. So, yeah, we should at least keep an open mind. But, at any rate, this other perspective--which people can achieve through meditation also, is a very liberating thing. And I think it really is--it provides comfort. Especially to the dying. And, to me, the most moving accounts of psychedelic experience have been on the part of people who had terminal diagnoses. And I interviewed several of them. And, that they were able to really reset their thinking about their death, and what it meant to them, and in many cases to die with a remarkable equanimity that I just could not--you know, seem--just remarkable to me. Russ Roberts: Because--it's one thing to say, 'I had a transcendent experience'. It's like, you take a trip to Yosemite, which is one of my favorite places in the world, and you can have a transcendent experience there. I often--I try to. Just from looking at the nighttime sky there, which is very different than my nighttime sky in suburban Maryland. But it doesn't usually change how you behave afterward. And yet, many of these people you are talking about right now, people who are diagnosed with cancer; others are healthy people who just go through this experience--the effects last beyond the experience. And not just, 'Oh, I remember that.' It changes how they interact with other people, to some extent. Michael Pollan: Yeah. And that's one of the most remarkable things. To different degrees. I mean, the depressed patients who have had these experiences, their depression lifts for a matter of months. But then they subside again. To many of the cancer patients, the changes were, you know, more enduring: 6 months out, they still had, you know, measureable reductions in anxiety and depression that were sustained. And, in the case of some of the addicts that I talked to--people trying to quit smoking, for example--a year out, they were still abstinent: 67% of them were still abstinent. So, I think it depends on, you know, on the individual and what you are being treated for. How is that happening? We don't really know. We do know that during the psychedelic experience the brain is temporarily rewired. I mean, this has been mapped. There are--a great deal of new connections spring up between parts of the brain that don't ordinarily talk to each other. And I show one of these maps in the book. And some of those new connections may or may not endure. The work that needs to be done, and is being done now, is imaging the brains of people before and after the psychedelic experience to see if there are any persistent changes. But, if you measure psychological changes through the usual methods of surveys, questionnaires, they have found measurable changes in the personality trait called openness. That's your ability to take in new ideas, deal with new people and unusual perspectives. It correlates with creativity. And this aspect of personality does seem to change in measurable ways. Even in adults. And that's very unusual. For the most part, adult personality is fixed in your early 1920s and never changes. But, psychedelic experience appears to have the potential to change it. And in a positive direction. Openness is generally considered a positive character trait. |

| 26:15 | Russ Roberts: So, one of the challenges of this research, which you are very open about in the book--I can't know how even-handed you are in the book, but you come across as even-handed; so congratulations. You have skepticism; you realize that some of the people reporting these results have an axe to grind. They want these drugs to be more available. You mentioned, for example, a patient is facing their death with more equanimity: that's a beautiful thing. Maybe we don't hear about the ones who go stark raving crazy after the use of the drug and have horrible, worse experiences down the stretch. Perhaps. That's always the worry in these kind of-- Michael Pollan: Well, it's worth pointing out, though, that no one in the clinical trials--and that represents about a thousand people who have been given psychedelics in this controlled setting in university trials--there have been no serious adverse events. So, no one's gone crazy in that cohort. Russ Roberts: At least in the formal sense of 'gone crazy.' But maybe they have a [?]--maybe their view becomes bleaker, and that's in the--the one third that don't have this soothing release after the experience. Maybe they have a really bad experience. They don't know, right? Michael Pollan: Yeah. Well, some of them--you know, many people had patches of bad experience. I think it's important to know, it's not all sweetness and light. People went into their bodies and confronted their cancer. They had moments of great terror. But they were succeeded by other moments. So, the so-called 'bad trip'--which the therapists prefer to call a 'challenging trip,' can actually be very productive. But, you know, yes. People react with, you know, episodes of great anxiety and upset. But, on balance, if you ask them afterwards, most of them are, you know, very happy they had the experience, and they found it very productive. Outside of this clinical situation, some people have had psychotic episodes. And there are no doubts in cases of suicide that you can link to an LSD trip. So, there are risks associated. You asked me a little earlier about this. And I was very, you know, personally nervous about doing this--having these experiences-- Russ Roberts: I would guess [?]-- Michael Pollan: so I did my due diligence as a journalist. And I looked at the whole question of risk. And it's really interesting. First, physiological risk: If we wanted to divide it into physiological and psychological risk, physiologically, LSD and psilocybin are remarkably non-toxic drugs. There doesn't appear to be a lethal dose of either. And you should know that there's a lethal dose of many over-the-counter medicines in your medicine cabinet right now. You know--pain killers, and antihistamines--all this kind of stuff is more toxic than LSD. Which--I was so surprised to learn that. They are also not addictive. That, these are not drugs of abuse in that sense, in that they--if you set up, you know, that classic test where you put a rat in a cage and you give a lever that administers drugs to its bloodstream, or another one that gives food; and if you put cocaine in that setup, the mouse or the rat will press the lever over and over and over again until it dies. Russ Roberts: As will some humans. Unfortunately, tragically. Michael Pollan: Yeah, without question. But, if you do the setup with LSD, the rat will press the lever once and then never again. It's just too disturbing an experience. And your reaction after having a big psychedelic experience is not, 'Where can I get some more?' It's just like, 'Do I ever have to do this again?' It's just too intense. There's no physical mechanism for addiction, either. Russ Roberts: That rat, of course, after that one time, loves all the other rats in a very beautiful and poetic way. Michael Pollan: I don't know that rats know how to process the experience. My guess is-- Russ Roberts: yeah. Love to know. Love to know-- |

| 30:17 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk a little bit about your experiences. You mentioned--without reading the book or being an intense meditator, which I have been from time to time--I think it's very hard to understand what you mean by the dissolving of the ego. So, perhaps you can tell us in general what you experienced. You tried LSD, psilocybin, and toad-something. Talk about that generally. But, in specific I'd like, if you'd care to, tell us about when you were listening to the Bach and the way the cello sounded to you, you were experiencing. Because I thought that was really--it was amazing. Michael Pollan: Yeah. Well, that was my, um, second guided journey. And that was on psilocybin. And I was trying to do the same dose that was being used in the clinical trial to get a sense of what the people I'd been interviewing were feeling. And, um, at a certain point during that experience, where I was on the--you know, the maximum dose is about 4 grams of dried mushrooms--um, I looked out, and I saw myself--and I know this is going to sound weird--kind of explode into a sheaf of little post-it notes, and getting blown around in the air. And this other eye opened up that was observing this scene. But it was clearly me. Yet I was fine with it. I had no desire to pile those little slips of paper back together and to reconstitute myself. And then I looked out again, and I saw this self, recognizable as me, spread out over the landscape like a coat of paint or butter, very thinly spread. And again, I was untroubled by it. And I--the usual borders between me and the world had vanished. And it was the most uncanny thing. It didn't feel bad. It felt fine. I mean, it didn't feel ecstatic. It felt fine. But as time went on, I did, as you alluded to, have this experience with music. I was having a lot of arguments with my guide about music. She was putting this, playing this New Age music that just seemed--I don't know--trivial for what the experience I was having. It was the kind of music you might hear when you are at a high-end spa, when you are getting a massage. So I finally said, 'Can we put on some classical music?' And we agreed on a piece by Bach, who has these gorgeous unaccompanied cello suites that Yo Yo Ma had recorded. And, she put on one: it was the Number 2 in D Minor, which is one of the saddest pieces of music I've ever heard. And, in fact I've heard it before at funerals. Um. And I listened to this music in a way I'd never listened to any music before. Indeed, the verb 'listen' just doesn't do justice to what was a complete, um, merging with the music itself. It became me. At one point I felt like I was inside that well of space inside the cello. And, it was my mouth. It was my skull. And I felt the bow with the horsehair going over the strings right above me. And I--it was as if that friction, I could feel that friction. I was the cello, and I was the music. And it was--it was just a wonderful experience. It wasn't all happy. Because it was all about death. Music was about death; I'd been contemplating death. But it was so beautiful that it reconciled me to death. It made me feel like I'd been lifted, you know, past the point of any kind of suffering or regret. And I felt that if I were to die at that moment, it would be fine. And I think this gave me a little bit of the insight into what the cancer patients were feeling. This, this sense that, um, that, you know, what makes it, I think, particularly hard for us to die is we are individuals. And we have a very strong sense of individuality--that we are bounded-- Russ Roberts: attachment-- Michael Pollan: Attachment. And we are bounded by the skin and bones, this meat sack we are in. And that the loss of that is the loss of everything. But, if you identify with something larger than that, whether it's the natural world or your offspring, your family, your community--suddenly your own personal extinction doesn't matter in quite the same way. And, um, this is an idea that Bertrand Russell wrote about. Somebody asked him, 'How do you die well? How does one die well?' And he said it was really a question of expanding of your sense of what is your sense of what is your self. How broad is that? Is it just your body? Or is it something larger? Is it the ideas you are invested in? It could even be your sense of the nation you are part of. Whatever it is. And, to the extent you can expand that late in your life, that makes death easier to contemplate. I think, you know, if you go back before Western civilization, you know, before the strong sense of the individual that we have gotten from the Enlightenment, of capitalism, and the whole ideology of American individualism, my guess is: Dying meant something different then. And was less tragic, in some sense. The psychedelics kind of put you in touch with that broader sense of self. And that's a very powerful thing. And as you suggest: Meditation does that, too. Without question. There are remarkable similarities between psychedelic experience and the experienced meditator. And in fact, when you scan the brains of both--someone on psilocybin or LSD or someone who is meditating--you know, someone with a lot of experience meditating in an fMRI [Functional magnetic resonance imaging]--their scans look very similar. The same parts of the brain are deactivated. And, so that, that consciousness--psychedelics are not the only path to achieving that consciousness. |

| 36:25 | Russ Roberts: I want to come to meditation in a minute. But, before I do, I want to stop on that set of observations you made about your own personal experience. You also talk about the incredible love that you felt for your family; your gratitude. Which also can be common in meditation. Michael Pollan: Yeah; and is part of that sense of connection, I think, I mean that comes: When the ego defenses come down instead of patrolling this border, they are opening--these channels are being opened. And what flows through those channels very often is love and gratitude. Russ Roberts: And again--that that can persist after the experience, is fascinating. It's obvious, when you tell someone or you tell yourself, 'Boy, I'm lucky. I have a wonderful wife. I have incredible children,' which I do feel blessed to have. That's nice. But the question is: How often do you think about them? And the answer is: If your ego is big enough, not so often. Because you are really worried about 'Me' a lot of the time. And I think what you are describing is something that gets inside you in a way that doesn't when you are just reading, say, a Hallmark card, or a--even though these are, as you point out, many times somewhat banal and cliche'd thoughts--the fact that they persist is not banal or unimportant. Michael Pollan: Yeah. Well, the line--one of the things you learn is the line between profundity and banality is very fine-- Russ Roberts: It sure is-- Michael Pollan: And, our brains are tuned for novelty, you know? We are--you know--with good reason. It was very adaptive to notice new things in the environment, and take familiar things for granted. And one of the things that happens on psychedelics--and this can happen through meditation, too--is a deep appreciation of the familiar. You know, of the woman you've been in a relationship with for, you know, 30 years. Of your children, the wonder of having children. And the wonder of love. And, so, I work very hard in the book to describe that, and kind of-- Russ Roberts: you do a great job-- Michael Pollan: and finally I conclude that, you know: Yes, these are platitudes: that love is the most important thing. But what is a platitude? It's a truth from which all the emotion has been drained. And you can re-saturate that dried husk, in a way. And psychedelics can help you do it. And suddenly you feel it with that full force. And it's a wonderful thing when it happens. Russ Roberts:The other thing I want--and, by the way, I know some listeners have stopped listening already, but I'm sorry that they're gone; I know a lot of people are thinking, 'Well, this guy's crazy. This is obviously...'. And you concede that in the book, many times. You write, "I feel funny writing these words." And you describe the kind of things you just described. But, I think the other part of this that's so fascinating, and you made the point that, before the advent of this individual this was common: I think before the advent of--before the death of religion, this was also common. When religion was more a part and parcel of everyday life, people were not as afraid of death. They were less potentially egotistic, or at least encouraged to be. And we do live in a culture, now, I think--certainly the culture you and I live in--much of it is designed to enhance the ego rather than subdue it. But the other part I'd like you to just reflect on--and then we'll get into some philosophical and science issues, and this will lead us in there--is that you were forced through this experience to confront some of your--and most of our culture's--long-held views about the physical and the material. Most people believe in--educated people, at least--that, this is all there is. We've talked about this a number of times on EconTalk. That, you know: The physical world, what you can measure, what you can see--consciousness is just some electric things going on in your brain. They are not just some chemical reactions. What you experience could be argued, as you concede many times in the book, just a drug reaction, perhaps. There's nothing real. There's nothing really--you are not getting access to anything deep and true. And yet, the people who undergo these experiences--akin to what I would call religious ecstasy or I would call prophetic experiences that we have described to us. They don't think of this as, like, 'Oh, that was really fun,' the way we might when we, say, get drunk. They see it as a real thing--that they had an authentic, valid experience of something ultimate. Michael Pollan: Yeah. And that, you know, that quality--William James wrote about this in Varieties of Religious Experience. And he talked a lot about the mystical experience. Which is very similar to the kind of ego dissolution I'm describing. And, in fact, they may just be different words for the exact same thing-- Russ Roberts: yeah-- Michael Pollan: And one of the hallmarks of the mystical experience, he wrote, is something called the noetic quality. By which he meant this sense you have that what you have perceived, the epiphany you have had, are not subjective. They are not just in your head. But that these are revealed truths of the universe. And you have learned something: These are like tablets that have come down from on high. And the authority of the experience is one of the most striking things about it. And many people do emerge from the experience thinking they have glimpsed a beyond of some kind--heaven or hell or God. And it's, um--you know, who are we to say that they are wrong? The fact is, James said about that, you know, "Judge these experiences by their fruits." Does it, you know, make someone a better person or not? That's really the key, since we can't really know. But it may well be that psychedelic experience is at the root of religious experience. And that it really--one of the things it has contributed. Because, remember, these drugs have been used for thousands of years, in a great many different cultures. And they do nurture the idea of it being odd, of another world besides the one that presents itself to our senses, that we normally think is the only one. And that's a very--to have that experience is, you know, it's an experience. And, um, people interpret it different ways, though. I mean, there have been--to give you an example: So, you can put a religious gloss on that and say, 'Well, I witnessed the beyond. I had a glimpse of heaven,' or this plane of consciousness that survives us after we die. And you can think of that whatever you will. But then, Carlo Rovelli, who is an Italian physicist, gave an interview recently. He wrote Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, and he's a prominent Italian physicist. He said that he had had an LSD experience when he was 15 or 17 that actually had opened up physics to him, and that he had an experience of time, where it was no longer past, present, and future, but it was kind of more like space and you could go in any direction, and the present was eternal. And after the experience was over, he said, 'Well, how do I know that that experience is false? And my everyday experience of time, as, you know, having an arrow and going in one direction and linear, is right?' And, in fact, physics tells us it's not right: that there is a beyond. That there is a whole other structure to reality that's very different from the one we perceive. And so, he came out of the experience with a healthy appreciation of a beyond, a scientific beyond. So, it's--you know, this takes us into interesting areas. And very exciting. I don't pretend to have the answer to what's going on. But, it is important. One of the things it does is it kind of relativizes everyday normal consciousness--that we take as the whole kit and caboodle. And in fact, it's not. That, there are other forms of consciousness that are available to us. The truth value of this one over that one is, you know, that's a matter of debate-- Russ Roberts: to be determined-- Michael Pollan: Yeah. To be determined. Yeah. |

| 44:25 | Russ Roberts: I was struck by the braveness of your book. Some of the things you write must have been--well, they are very vulnerable. They make you very vulnerable. So, obviously they are partly the result of your experience. But, certainly friends of yours and others have sneered, I suspect at some of your claims and thoughts. Have you experienced that? Michael Pollan: No, actually. People have been-- Russ Roberts: You have good friends. Michael Pollan: Yeah, I guess so. [?] I'm meeting the wrong people. People have taken it--I've tried to be very matter-of-fact about some very personal issues, about my experiences, how weird they were but also how profound they were. And I find that to the extent you are matter-of-fact about such matters, other people are, too. And they kind of take their cues--whether I'm talking to someone interviewing me on television or a friend. People tend to take you on your own terms, I think. Maybe behind your back they have another take. But I resolved when I was doing this to write as honest a book as I could and not be concerned about how I looked--or, you know, I did have a public reputation and--but, you can't explore this realm without revealing something about who you are, and revealing your vulnerabilities, and things like that. So I just decided, 'Surrender,' I mean, in a way. And the same advice I'd gotten about the psychedelic experience, I took to the literary experience: to surrender to it, be as truthful as I could, tell the story to the best of my ability--as hard as it was, in places. And so far, I haven't--I don't think I've paid any negative price for that at all. Russ Roberts: And you get a best-selling book out of it. So, that's a good thing. Michael Pollan: There is that. Russ Roberts: I am reminded, when you are talking about the religious part I was reminded that there is a famous Jewish story of four rabbis who go into the orchard. And, what the orchard is, isn't exactly defined. It could be a physical place, but it's generally conceded not to be a physical place. It's some kind of mystical, spiritual, out-of-body experience. Of the four, one goes crazy. One kills himself, I think. One becomes an apostate. And, only Rabbi Akiva, who is this giant figure, returns from the experience with his wellbeing intact. And that--and I mentioned the prophetic experience, where prophets will talk about being swept off their feet--overwhelmed--they are very reminiscent of the kind of experiences that you are talking about. Michael Pollan: Yeah. And, you know, there are remarkable similarities to mystical experience all through history. You know, one of the things, one of the experiences I had, was, after having my high dose psilocybin session, there was a whole tradition of writers in America and England, and elsewhere, too, writing about their mystical experiences. You know, there's Emerson on the Boston Common who feels himself transformed into a transparent eyeball and the currents of nature flowing through him. And there's Walt Whitman in the early drafts of Leaves of Grass talking about this, alluding to this experience where he felt like God was controlling his hand in some sense. And Tennyson has them. And Wordsworth. And all these experiences. I read this and I thought it was just literary conceits. You know?-- Russ Roberts: Yeah. Poetry-- Michael Pollan: It just had no--it was poetry. Yeah. It was poetic. And now I can read that, and I was like, 'Ohhhh. That's what they're talking about. That's a real experience.' And, so it opened up this whole tradition. And I haven't read widely in it. But, Meister Eckhart and all these medieval mystical experiences--this is just a line that goes through the West. And of course the East, too--Buddhism and Hinduism. And, suddenly those words have meaning in a way they didn't for me. And that's very exciting. I feel like it's opened up this door that, you know, I've only just begun to go through. Russ Roberts: I think there are\ skeptics, either religious skeptics or psychedelic skeptics--I think they would listen to this and say, 'Yeah; those are just--people are crazy sometimes. They experience things'; but you are calling them psychedelic, mystical. They also could be described as psychotic. People having out-of-body experiences, thinking they are communing with the divine, seeing the unity of themselves with nature: That's just some wire that gets crossed in some neuron that misfires. And, 'That's just some crazy inside-the-brain thing.' Michael Pollan: Yeah. And it could be. It could be caused by the Default Mode Network going offline. Which is one, you know, interpretation. Russ Roberts: Well, say what that is--the DMN, the Default Mode Network. Michael Pollan: Well, one of the interesting findings, when they began to image the brains of people on psychedelics--and meditators, as I mentioned earlier--they found, to their surprise that instead of the brain looking like, you know, this hotbed of new activity, a very important brain network call the Default Mode Network. Which is a tightly linked group of structures in the midline that links parts of your cortex, which is your, you know, executive function, the most recent part of the brain, with older, deeper centers of memory and emotion. And this is a very important hub. And it's also a regulator of, you know, global brain activity. And this goes quiet--this is down-regulated--during the experience. And that was really interesting. And, indeed, the more down-regulated it was, the more likely someone was to report an experience of ego dissolution. So, the Default Mode Network is involved, it appears, in generating this sense of self that we have. It's where we--where self-reflection appears to take place. Self-criticism. Time travel--the ability to think about the future or the past. Theory of mind. The ability to imagine the mental state of another--which is very important to moral reasoning. Obviously; and compassion and empathy. And also something called the narrative or experiential or autobiographical self. And this is the kind of part of the brain that, where we, essentially generate stories about we tell ourselves about. Who we are. Russ Roberts: Our self-narrative-- Michael Pollan: Yeah, self-narrative, that gives us the sense that we're a continuous person over time. Which is, you know--a hard-won[?] thing. Because we're not. And so, when you take this offline for a period of time, interesting things happen in the brain. Your barrier between self and other comes down; and you have this sense of merging. But you also have other interesting things happen. And that is that the brain--parts of the brain that don't ordinarily talk to one another, that usually just go through the Grand Central Station of the Default Mode Network, start striking up conversations with one another. And so, you might have, for example, your sense of smell talking to your sense of sound. And that may manifest as what's called synesthesia--the cross-wiring of senses that happens very often on psychedelic experience where you can see sounds, or smell them. And we don't know what else happens, though, we've mapped this new communication. But, those new lines of communication may be new insights, may be new metaphors, may be just new ways to connect the dots. They may have implications for creativity, insight. You know, we don't know. I mean, there's so much more to be learned. And, what's exciting, though, is that--and this is really, my book is as much about this as about anything else--is that psychedelics are a tool for understanding the mind. A new tool. And an old one. And that, that's what's most exciting: That you learn, not just about the psychedelics, per se. That's fine. It's interesting. But, it's a window on the mind and on everyday normal consciousness, and on the senses, and on the self. All these things are thrown into high relief by this experience. |

| 52:48 | Russ Roberts: Yeah, there's obviously an incredible level of self-awareness that potentially comes from it. I want to reflect a bit about meditation. I've attended three silent meditation retreats in the last two and a half years. They were Jewish in character with a little bit of Buddhism, in terms of technique. And I thought, 'Well, this is going to be really hard. I'll never be able to stay silent for 5 days.' But that turned out to be the easy part. The hard part was confronting myself. And if I had to summarize what that experience was like, I'd say, well, they made me less egotistical, more prone to being overwhelmed with awe. Soften me. Made me more emotional. I think made me a better husband. A better father. Better friend. Made me more aware of my modes of thinking, patterns and grooves I've been stuck in; reduced a lot of visceral fears, anxieties. At times made me--not always--but at times made me much more compassionate than I could have imagined myself being capable of toward both strangers and friends. And this strikes me as a pretty good summary of how you describe as the single use of a particular psychiatric[?] drug. And, other than that observation: How do we understand that? Could I have skipped those retreats and eaten a mushroom? Is LSD or psilocybin a shortcut for those kind of experiences or for psychotherapy generally? Because I had a huge pyschotheric[?]--I'd never been in therapy, but these retreats were very, very therapeutic, in forcing me to confront aspects of myself and to change the way I looked at myself. And that's similar to what you--it's not similar, it's the same thing. Michael Pollan: It's very similar. And I do think that, in a sense, psychedelics are a shortcut. But they have limitations in that you can't do it every day. Whereas, you can meditate every day. And, one of the fruits of my own experience has been to take my meditation practice a lot more seriously, and really work it. Because, I found it is the way to really reconnect with that kind of consciousness I was describing earlier. You know, after I had that big experience on psilocybin of ego dissolution and my merging with the music, in my integration session with my guide, who, in the book I call Mary, I told her--I said, 'You know, my big takeaway from yesterday was the fact that I don't have to identify with my ego all the time.' And that there's another ground on which to stand. And, you know, meet life. And what life throws at us. And she said to me, she said, 'Isn't that worth the price of admission?' And I said, 'Yes. It is.' But, on the other hand, my ego is, you know, I'm back to baseline. My ego is back in uniform. On patrol. So, what good was that? And she said, 'Well, having had a taste of another way to be, another kind of consciousness, you can cultivate that. You can nurture it.' And I asked her how. And she said, 'Through meditation.' And that meditation is the way you take whatever insights you've achieved on psychedelics and incorporate them in your life. And that was a very important lesson. I haven't done a silent retreat yet. It's something I'm very eager to do. And, you know, talk to me in a year and I think I'll be able to say more about the continuities between psychedelic experience and meditation. But, you know, the brain scans suggest that they are very similar, and phenomenology, too, I mean that people describe as very similar. You know, many of the most famous American Buddhists--people like Jack Kornfield and other names that are escaping my mind right now--they, they started on psychedelics. And they were looking for a way to sustain that kind of consciousness they had had a taste of. And they found they could do that through meditation--whether it was Tibetan Buddhism or Zen. And--Joan Halifax is another one, I'm sorry, who was very involved with psychedelics at a certain point in her career. So, you know--and I talked to a neuroscientist and psychiatrist who studies meditation--and he can foresee a time when psychedelics might be kind of used to kind of kick-start a meditation practice. Because, one of the confusing things, if you can remember back to when you started, is like, you know, everybody is always saying, 'Am I doing it right?' And, I get that. And, if you've had a real taste of the destination--I know I shouldn't use such purposeful words, but 'striving for--' Russ Roberts: Bad Buddhism, for sure. Michael Pollan: Yeah. Bad Buddhism. But if you've seen it--if you've had a sample--it becomes much easier to find your way back to that. And that certainly has been my experience. Not consistently. I have to work at it. But it's there, and I recognize it when I hit it. Russ Roberts: My practice is very uneven. I struggle to meditate every day. I try to, but I don't do that successfully. And, like anything else, like you are saying, it's up and down. There are times when it's extraordinary; but many of the times, I would say most of the time, and I would say this is true for my religious practice as well: It's very mundane and nothing really dramatic happens. |

| 57:56 | Russ Roberts: What I find fascinating, though, is the--and I'm curious your reaction to this: At the highest level, whatever you want to call that, when I was at one with a sparrow I watched for half an hour on retreat, or, you know, I had an ability to slow my mind down and be extremely expansive and watch thoughts arising--I haven't been able to do it since, but it is something to strive for--so, it really can be an extraordinary change in how you experience, as you say, the most mundane parts of your life: seeing your wife, who you've seen almost 29 years, almost; your children; the flower that is blooming by the door; the bird perched on your deck; etc. They can have a vividness that makes your hair stand on end. In a beautiful way. Like a great piece of music. [More to come, 58:46] |

Journalist and author Michael Pollan talks about his book, How to Change Your Mind, with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. Pollan chronicles the history of the use of psychedelic drugs, particularly LSD and psilocybin, to treat addiction, depression and anxiety. He discusses his own experiences with the drugs as well. Much of the conversation focuses on what we might learn from psychedelic drugs about their apparent spiritual dimension, the nature of consciousness, and the nature of the mind.

Journalist and author Michael Pollan talks about his book, How to Change Your Mind, with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. Pollan chronicles the history of the use of psychedelic drugs, particularly LSD and psilocybin, to treat addiction, depression and anxiety. He discusses his own experiences with the drugs as well. Much of the conversation focuses on what we might learn from psychedelic drugs about their apparent spiritual dimension, the nature of consciousness, and the nature of the mind.

READER COMMENTS

Chase Steffensen

Jun 25 2018 at 12:50pm

Russ, I’m so excited for this interview!

I’ve already listened to Pollan on Joe Rogan and Sam Harris, then I bought and finished the book very recently. I’ve been burning to tweet to you that you should have him on.

This is also the first time I’ll have read the topical material before listening.

Mike

Jun 25 2018 at 3:58pm

There aren’t very many high-profile people courageous enough to speak openly about the benefits of psychedelic use. Listen to how cautiously the host approaches the subject. Props to him for bringing Michael Pollan on the show because Pollan is doing a great job speaking to the science and the experience itself.

My perspective changed completely around five years ago when I grew and had my first psilocybin mushroom experience. The proof is in the lasting behavioral changes that follow.

Psilocybin spores are legal to buy and easy to grow, however once the fruits have developed it becomes a schedule 1 drug in the US, so be mindful of the laws in your jurisdiction.

Jordan

Jun 25 2018 at 11:12pm

This was very interesting! As a very religious person (Christian Scientist) I’m always excited to listen educated people who are even remotely open to the idea of a Higher Reality, especially one that can transform human lives– or in my experience–a Reality that can radically improve the bodily condition.

Earl Rodd

Jun 26 2018 at 7:52am

I have a comment about the CIA part in LSD research. This is not important to the theme of the interview, but it is interesting. My understanding from people I knew who were in the psychological division of the CIA in the 50’s and 60’s is that a lot of the LSD (and other substances) research done in academia was funded by the CIA, often via the Human Ecology Fund. The Human Ecology Fund was also used for other research funding. A lot of this is described in John Marks’ book on the larger MKULTRA project, “In Search of the Manchurian Candidate.” I cannot vouch for all of Marks’ book, but someone I know who was interviewed for the book said that his part was faithfully recorded. I think that Marks is correct in saying that the driver of the CIA funding such research was concern that if there were a miracle drug that could either A) be a “truth serum” or B) make someone forget why they are here and who sent them, and the Russians found it first, we would be in trouble. While such a miracle drug did not arise, the powerful Personality Assessment System of John Gittinger did and was an important tool in CIA practice for many years. Sadly, the Senate hearings on MKULTRA were too much about lurid parties etc. and not enough about important things (thank you Senator Kennedy). John Gittinger, who just wanted to talk about his Personality Assessment System, was so upset with the hearings that he retired prematurely. Having had the privilege of knowing Mr. Gittinger, this was a real loss to US capabilities.

Dan

Jun 27 2018 at 4:48pm

Maybe its the Midwestern sensibility in me, but I have a lot of issues with this topic. In fact I don’t know where to begin, but here goes:

The same rationale Pollan is saying- its safe now because it is administered or assisted by a Dr. or some other medical authority- is the same thing we heard about opioids. We all now how that’s turning out. Do you really think this would stay in a Dr.’s office? How many people would now get LSD on the street, have a bad trip and kill someone or themselves?

We also heard that opioids weren’t suppose to be addictive but turns out they are. And even if I believe that LSD is not addictive, it can certainly be abused, as name your favorite 60’s rocker or hippie whose mind is now fried because of LSD and Acid.

LSD appears to re-wire your brain according to Pollan. What? Do you think people want their brains re-wired? I sure don’t. Who knows what the long term consequences of that would be? And do I get a do-over if I don’t like the way it was re-wired? Doubtful.

LSD is a dangerous drug, and I would have hoped Russ and his guest would have turned more heavily to some non-medicated methods to achieving their ends such as meditation and prayer. They did, but not enough in my opinion.

Joe

Jun 28 2018 at 1:41am

I also am suspicious of the doctor angle, and the authority/gatekeeper model in general. People have been using entheogens for thousands of years before white lab coats were even invented.

As you acknowledge in your post, you have a lot of “issues” with this topic and “don’t know where to begin”. This is apparent in the remainder of your post. What are your premises? What is the conclusion? Entheogens are dangerous? Relative to what? Even if you’re correct, so what? Entheogens should be illegal? Not illegal, but morally frowned upon?

I am also from the Midwest, and I take a bit of umbrage with you using the character of the region as cover for not researching the topic in depth and reaching a carefully considered conclusion – not Midwestern at all in my experience.

Kudos to Russ for both the topic and for how well he conducted the interview.

George McQuistion

Jun 27 2018 at 8:54pm

First, I feel there should be a link somewhere on this page to the book Powers of Mind by George Goodman (pen name “Adam Smith”). Written in 1975, this may have been the first popular book to explore consciousness, the use of psychedelics, meditation, etc. from an “establishment” writer, who was much more comfortable on Wall Street than in Haight-Ashbury. Like Mr Pollan, Goodman was sincerely trying to discover what these substances & practices could reveal about the human condition, also sharing his experiences with them.

Second, for those meditators looking for some ego dissolution, here is a nice short guided meditation with the aim of doing exactly that. The meditation is called Busy Life, No Self and is by Joseph Goldstein, a friend/colleague of Jack Kornfield. (click on link, then scroll down for the audio player).

Great podcast…thanks!

Daniel Barkalow

Jun 28 2018 at 8:11pm

There’s similar research into using MDMA as a catalyst to psychotherapy (particularly for post-traumatic stress disorder, but also for anxiety related to terminal cancer), which I’m more familiar with. This combination has a lot in common with using anesthetics in surgery: you have a reasonable treatment for the underlying problem (surgery or therapy), but the process is too painful for the patient to tolerate it. However, a drug can be used to make the process bearable, and then the procedure that actually addresses the problem can be carried out successfully.

I suspect that this is also the case in therapy with psychedelic drugs, where the altered state the patient is in allows for a productive examination of problems that are otherwise too entangled and unapproachable. I would guess that Michael Pollan didn’t really get this in his experience, because he didn’t have this kind of problem to work on.

This is the way in which having a shortcut to the sort of mystical experience that you can get from meditation is particularly valuable: if you’re very good at meditation, you can come to endure pretty extreme pain, and you could probably sit still while a dentist drilled a hole in your tooth. But if you’re new to meditation, and you’ve got a toothache, and you’re trying to learn to meditate in the dentist’s chair, there’s no way that’s going to work. Likewise, if you’re already great at meditation, and you develop a mental problem that’s hard to address in default mode, you can meditate and work on it. If you aren’t yet great at meditation, and it’s hard to quiet your intrusive thoughts enough to leave the house, that’s not the time to start learning to meditate. You need the shortcut, because the long way isn’t available under the circumstances.

Mike

Jul 1 2018 at 8:57pm

I’ve enjoyed these recent interviews about psychology, meditation and other ways of being in the world. Thinking in terms of interests and incentives is extremely useful for protecting yourself and getting things done, but if that perspective gets too powerful it can make life miserable and undo everything it tries to achieve.

I’m not a religious or spiritual person. It doesn’t ring true to me that in meditating you are recognizing some deeper connection to the world. For me it is about reminding myself that the purposeful, critical perspective is flawed and is something that I can get away from when I need to. It is easier for me to definite this alternative, right-brain perspective in terms of what it isn’t rather than what it is.

Aaron Kurz

Jul 18 2018 at 7:51pm

You should consider talking to Sam Harris on this. He’s more than just the anti-religion guy.

I really want to try a psychedelic or meditate now. I’m too lazy to do one, and too scared to do the other. Just kidding…I’m too lazy to do either. #priorities

Joseph Kozsuch

Jul 20 2018 at 9:27pm

I’m not surprised by the “ego inflation” of psychedelic drug users and meditaters. Their trips and meditations are all about looking into their own mind. All of the connections to their surroundings stem to the meditater. It’s a personal experience.

I support being self-aware (and am a daily meditater), but we shouldn’t discount that these are pursuits for our own well-being. There are other ways to be better human being. Drugs and meditation are possibly an enhancer, but not a cure-all.

Comments are closed.