| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: June 7, 2019.] Russ Roberts: My guest is... Chris Arnade.... Today we are talking about his new book, Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America.... I want to let parents listening with children that this episode will almost certainly touch on a number of adult themes, so you may way to screen it before listening with your children. Chris, you've written a very powerful book that I think has a chance to spark a national conversation about the people who are not part of the progress that we've seen in America over the last few decades, people who sometimes are described as left behind. You describe them as people in the back row. How did you come to the experiences that you chronicle in the book? Chris Arnade: Kind of in a backhanded way. I didn't intend this to ever be a book, didn't really intend this to be more than just I guess a guy with a camera exploring the neighborhoods he was told not to go to. As you mentioned and we spoke about in the last podcast, I was a Wall Street trader for 20 years; and before that, I had a Ph.D. in physics and come to industry that way. And, one of the things I did was to take long walks--often 20-mile walks--and just explore the neighborhoods of New York. And those walks started to shift following the financial crisis when I realized that my industry and myself and a lot of people like me had really messed up and screwed up, and to re-evaluate kind of how I saw things and how I thought about things and how I learned things. In particular, this kind of sitting behind a wall of computers making decisions based on flashing numbers, and Power Point presentations and Excel spreadsheets was missing, you know, a voice, and missing the actual people we were making decisions about. So, I went--I kind of said to myself, 'I've been doing this quantitative, data-based approach to life so long--let me just talk to people.' And those walks provided me that opportunity, because when you have a camera, people open up. And so, those walks evolved into kind of me just going on a listening tour, I guess. And, one of those walks led me to the Bronx, which led me to the South Bronx, a neighborhood in the South Bronx I had been told not to go to--because the data said it had all sorts of problems. And so when I walked into that neighborhood I saw what the data didn't show, which was a thriving community with a lot of beauty. There was a lot of frustration there but the people were doing their best to make it a functional neighborhood. Russ Roberts: These were--a lot of the people you met there were people that--those of us who have not been to that neighborhood were people who would not be described necessarily as successful. They are drug addicts, drug users, prostitutes; a lot of homeless people. Correct? Chris Arnade: That's correct. That wasn't my initial focus, but that's what my focus became as I spent more time there and I realized that not only was this neighborhood stigmatized unfairly in my mind, but within that neighborhood was another community that was stigmatized even more, and that was those who were suffering from addiction, or sex workers, or those who were living on the streets. Those all three go basically hand in hand. And so I shifted my focus more towards that, initially out of kind of curiosity but then became somewhat political, I would say, in the sense that what I was seeing amongst this population [?] was like what I was seeing in this neighborhood were stigmatized I thought unfairly. And, the kind of stereotypes that we were using to stigmatize them were just that--stereotypes that were wrong. Russ Roberts: What drew you to that--to that neighborhood--do you think? Chris Arnade: Part of it that--there's some simple things. You know, it's really like a small town. I think a lot of big cities are really just collections of small towns that adjoin against each other. And this one in particular--it's Hunts Point--because of the geographical location, it's basically in a walled community. It's isolated on three sides by--it's like a tongue of land that juts out into the East River, right across from LaGuardia with Rikers [Rikers Island, New York City jail and correctional center] in between. It's a tongue of land that sticks out, and so, on three sides it's surrounded by water, and on the fourth side where it attaches to the Bronx, there is a pretty-engineered road, elevated road, the Bruckner, which I believe is 6 lanes; and it's just brutal; and it effectively cuts the neighborhood off from the rest of the Bronx. So, in that sense it's a very knowable[?] place--it's 35,000 residents. I like to say that New York City puts whatever it doesn't want there. It puts, you know, junkyards and industrial plants and other things that it doesn't particularly want. So, the neighborhood has a lot going against it, in that sense. But, it's also 35,000 people who make it a real community. And that community--the knowability, and also just as a photographer, the light--it's south facing, so it gets good light, which makes for strong photos. |

| 6:54 | Russ Roberts: So, you started going down there occasionally, and then you started going down there every day all the time. Correct? Chris Arnade: Correct. It ended up being basically 3 years' of being there--7 hours a day, 8 hours a day, 4--depending on the situation. And that required me basically quitting my job, at some point. Or, they quit me. So, when that buyout opportunity came, I accepted it. And, again, it wasn't really clear I was going to focus fulltime on this: I still was thinking maybe trying to find another job in a hedge fund or something. But, it just--it just kind of took over my life, and I felt more and more distance from what I had been doing. So, I shifted into this, this process of, I guess, documenting what I saw. Although, it became more than that. It became getting involved in the lives of some of the people, trying to help them, taking them to detox, visiting them in Rikers, taking them to the hospital. Things like that. Russ Roberts: You talk about letting them use your cellphone, your computer. This is a personal question; if you don't want to answer it, I'll edit it out. But, did you tell your friends and family you were doing this every day? Chris Arnade: Yes. Yeah. Russ Roberts: So, what did they--they must have been, in some dimension, taken aback or surprised. When I describe the book to people, some people look at me puzzled, like, 'Why would he do that?' You must have gotten that reaction. Or, they must have been afraid for you. And I assume there were times you were afraid. Chris Arnade: There wasn't many times I was afraid, to be honest. I think one of the misconceptions is about the danger in these neighborhoods. But, you know, there were people who thought maybe I was off my rocker. But, I was supported by my family, who, you know, I wasn't a traditional Wall Street trader; I came from an academic background. And, my parents were academics. So, I think, in some senses, I think I'm the only person from my college to have ever gone to Wall Street--which was a very leftist college. So, I think, in some senses, people that knew me all my life would say that me being on Wall Street was more of the anomaly. |

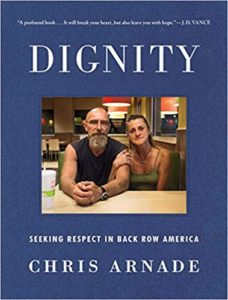

| 9:10 | Russ Roberts: So, after you did this for three years in the Bronx, you decided you wanted to look at a wider swath of people struggling, and the communities that you were interested in. So, tell me what you did, driving across America to continue this odyssey. Chris Arnade: Yeah. I basically, you know, and to put my old mathematics hat on, wanted to see if what I learned in Hunts Point in the Bronx was translationally invariant. Was it true elsewhere? So, I started finding neighborhoods that were stigmatized or forgotten or left behind or whatever term you want to use. They all are unfortunately demeaning--that's the problem with these terms, is that they quickly become demeaning. So I found places, you know, across the country, that I thought kind of represented a fair--that kind of would test my theories--you know that were different from Hunts Point but similar in some ways; and to see how stuff held up. So I think I ended up doing, I think, two years on the road? I came back a lot--I spent a lot of time back at home. But I'd go on these trips of maybe two weeks, three weeks, a week, six weeks, two months, depending on where my, kind of, destination was; and just go to communities where a lot of people live but that we rarely hear from. And also, and generally have a bad reputation. Russ Roberts: The other part that I think these areas have in common is there's not a lot of employment. There's not a lot of--whatever employment was there is gone. Factories have closed. So, you are looking at places that used to be somewhat thriving or thriving and are now desperately poor, in the financial/monetary sense. And the people generally are not working--a lot of the people are not working in traditional, 9-5 jobs. Would that be an accurate way to summarize the sort of economic environment, climate, that they were in? Chris Arnade: Right. But, I think--and some of the neighborhoods, though, were not far from successful neighborhoods. So, you, you know--South Bronx is very close to Wall Street. Very close to the Upper West Side. So, it wasn't just economic. I think they were neighborhoods within a larger community that was doing well but had been stigmatized. And in many cases by racism. But, yes: I think the majority of them were places that had lost jobs. Or, I think it almost became: Weren't close to an elite educational institution. I think that almost became the more defining feature of them. You know, they weren't attached, either in employment or reputation to a high-end college. Russ Roberts: You say they were stigmatized--and I hope we'll come back and talk about that. But, there are some objective aspects of these communities that are not related to the stigma. There's often boarded-up buildings. There are--when I say 'not related to stigma,' meaning: There are some visible things that are not going well in these neighborhoods--drug use, boarded up buildings, lack of steady work for most of the people. Often, people struggling in very ennobling--'noble' is not the right word--but there's a courage about some of the people you chronicle that's very apparent. But, these are neighborhoods that are not, on the surface, doing well, at least. Chris Arnade: That's correct. I almost feel like, I used to say, you could put a blindfold on me and drop me someplace in the United States and I can tell you within 3 minutes what type of neighborhood--if it's one of those neighborhoods. I could tell you maybe within 1 minute. You can put me in the grocery store, an aisle, and I could tell you pretty quickly. And it's not by looking at the people. It's by the products that are being sold, by how fresh the vegetables are. It's by how much [?], traffic engineering is there. You know. It's: These places don't have a lot of work put into them. And a lot is falling apart. Or, the work that's been put into them is kind of decaying, and it just wasn't the right fit. So, you can tell immediately. Very quickly. And, again, not looking at the people at all. Russ Roberts: Your book has dozens of color photographs. It's a strange book in the sense that, in many ways it's a portrait of, I think, people living--some subset of the people you talked to are, I would say, living a life of desperation. But it's also kind of a coffee-table book. It's a pretty book. And it's very powerful. It's, in many ways, I guess a better way--desperation is related to, at the root of it to despair. There's a lot of despair in the book, and yet there's also a lot of dignity. And lack of dignity. It's a powerful book. |

| 14:56 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about the role McDonald's plays in these communities, and how you came to see that in the time you spent there and what that's like. Chris Arnade: Right. I ended up spending a lot of time, and a lot of the book is focused on McDonald's. Because, that's where I--in these neighborhoods that was one of the few institutions that, for lack of a better word, worked. A place where, you know, you could go into one of these neighborhoods and perhaps on a Wednesday night, the sole thing that was kind of open and fully knowable and safe and functional was McDonald's. And the community used it as almost their Town Center. It's where people got together to meet. It's where--people play Bingo, people play chess, people play checkers, people play bingo--chess clubs meet there. And, the thing was, when my focus was primarily on homeless and addicted, that's also why, that also uses McDonalds. I kind of realized that in the South Bronx, where certainly McDonalds is central to the life of somebody who is on the streets. It's a place where they can go in and just escape the streets for a few hours, and the elements of the streets. And clean up in the bathroom. Maybe shoot up in the bathroom. Russ Roberts: It's warm[?]. Chris Arnade: Yeah. But also, free WiFi; charge your phone. But also, the big thing, I feel the more important thing, was almost a no-judgment zone. They can sit there and be left alone. Or interact with people on the terms of polite--I call it polite society, normal society, and not be stared at. You know, one of the things that frustrates me is that, as much as I love academics--I got a Ph.D.--but if a homeless person or an addict goes onto a college campus, they are going to have the police called on them. If they walk into McDonalds, they are able to sit there for a few hours. Russ Roberts: I could imagine it would go the other way. But it doesn't. Chris Arnade: Right. And so you know, it's just this place that becomes--I basically saw McDonalds in a different light. You know, I am on the Left, and so I am frustrated with McDonalds on many levels. But, the reality for the working class and the very poor is that McDonalds is essential. It's cheap food--I don't mean 'cheap'--it's inexpensive food that's pretty good. And, you know, so--if you are on a tight budget and you don't have much money and you don't have much time, McDonalds is essential. But, it's more than that. It's a community that evolves there. And I think it's just really important to realize--what I kind of started learning was, one of these things you learn when you talk to people and visualizing it away from data is that how important--people need a community. They need it so much that they form it in an institution that's designed to be entirely transactional. You know? Like, that's how much they want it. They want community that much. And socializing. And so, the social activity of McDonalds really struck me; and it became in many ways a light that went off in my head and said, 'I've been thinking about things so wrong.' |

| 18:20 | Russ Roberts: Before I get into some of the other ideas and impressions that you've gathered from your experiences, give us a little of the flavor of how you would talk to people on the street. You are walking around. You are a white guy, often in a black neighborhood, or a non-white neighborhood. You've got a camera. You stick out. How did you get people to open up to you? I mean, literally: What did you say to them? What did they say to you? How did you answer their questions? You give some examples in the book. So, share those, please. Chris Arnade: In general, my overall approach is--I tell this to people--is--and I really this; this isn't a gimmick--is: Have no fear. Don't be reckless. But, the rule I always use is: Be confident without being arrogant. And, also: Be there for the right reasons. If you are there with good intentions and you show that you trust people--and I do--then I find that that's reciprocated. People trust your. You know, the other thing is: one of my biggest frustrations is, people are scared of these neighborhoods. And there's really not a good reason to be scared of them. I mean, I'll put my old math-hat on again and say : If a neighborhood is bad--so supposedly it will be crime-ridden. So, in a good neighborhood, let's say 99% of people are playing by the rules, or, let's say, not criminals: in a bad neighborhood it's 94% of the people, 93%. The point is, the overwhelming bulk of people are still well-intended. And so, you know, focus on those 94/95%. People are tired of being stigmatized in these neighborhoods. So, if you come in with good intentions, people, people, people pick that up. In terms of how I approached, it was just generally walking around. And again, because so much of the book takes place in minority neighborhoods and I'm very white, people would often approach me, and just out of curiosity-- Russ Roberts: yeah-- Chris Arnade: And so that would start a dialog. And, you know, one of the things I--I would go wherever anybody asked me to go. I think a lot of people might think that was naive of me. You know. But I remember one case where I was in a neighborhood, in the, entirely, probably one of the most high crime-rated neighborhoods in New York City. And a gentleman who was clearly on drugs was really excited to see my camera. And he wanted me to come with him into an abandoned building that we had to climb, basically, a few rickety ladders that he'd constructed so he could live on the top floor. He said he wanted to show me something. And, you know, it was 6 at night and the light was dimming; and a lot of things told me I probably shouldn't go, but I did. And what he had to show me was he was a painter, and he had done a painting. He wanted to show me the painting. You know. And so, there were a lot of moments like that, where I trusted people. Now, there's a big difference here. I'm a male. I think females would have a much different circumstance, and I recognize that. I don't want to sound naive about that. But, um, yanno, another thing I would do if I saw somebody wasn't trusting me--let's say I meet a group of people in McDonalds who are used to being seen as criminals or are homeless and are used to being kind of stereotyped--what I'll do is I'll hand them my camera and say, 'Excuse me, I have to go back to my car to get something. Will you watch my camera?' And leave for 5 minutes. And come back, with having left them my camera. The implicit message is, or explicit, is: I trust you. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Chris Arnade: And every time I came back, the camera was there. You know. So, it was my way of saying, 'Here's a $3000 object. Here's $3000. I'm going to go; watch it for me.' So, you know, I think--it gets me frustrated. There was a time I was in Milwaukee, and I'd been there--it was the second week of being there and I had spent all my time in a very traditional black neighborhood. North side. And one of the things that's really wonderful about Milwaukee, the black community in Milwaukee, is it's directly from Mississippi. Because, almost everybody came in the 1940s and 1950s and they came in the same part of Mississippi. So it's this really, it's like this small southern town that's mixed with a northern town. And so, they have a lot of bars. Unlike in a lot of other poor neighborhoods, black communities, there's bars. That it's kind of the Wisconsin bar culture mixed with Mississippi. And so, I was saying to some acquaintances I knew in Mississippi who are on the political Left like me and are white, 'You know, I don't drink any more but I still go to the bars to have like a soda, or a Pepsi, just to talk to people.' And I said, you know, 'Hey, you guys want to go out tonight? I'm going to--' I think it was the Catfish Lounge. And they're like, 'I don't know, man. I think you'll get stabbed there.' And I was like, 'You know, I walked in and no one ever stabbed me. No one even thought about it.' You know, I got some odd looks, initially, when a white guy walks into the all-black Catfish Bar. But, by the end of the night, everybody was opening up, talking to me. They were just happy to have somebody come in and not worry about being stabbed. So, I think you've just got to be a little more open-minded about preaching off to other people. |

| 24:22 | Russ Roberts: To this experience--well, actually, let's start with--let me ask you about the metaphor you use of the Front Row and the Back Row, and your emphasis on credentials. One way you put is that you understood from a young age that if you went off to college and did the right thing, you'd escape your small town that you grew up in, in Florida. Certainly, in my circles, everyone is deeply, overly focused on their children getting into the best schools and see that, somewhat correctly--maybe not, but somewhat correctly--as the road to financial wellbeing. And, the populations you are interacting with in this book, they don't have good access to that credential machine. If they get access to it, they don't know the rules of the game, so they struggle to thrive in it. Talk about that culture that we live in--that you and I live in and they don't. Chris Arnade: Right. I kind of use the metaphor of the Back Row and the Front Row. I think we've built this kind of--we can shift talking about it later, but as our economy has kind of shifted into a kind of more focused, post-industrial kind of knowledge-based economy, the access to that is along this very narrow path that weaves through these certain institutions. And, the gain from that is huge. The difference between--you know, the gap between getting an education and not is growing. But, my biggest frustration is not only that. That's bad: I think we should kind of different ideas about success instead of this one institution. But, I think a lot of people don't understand how narrow that path is, and how you have to start at an early age and do all the right things. I'd say, I liken it to an escalator that goes up really, really fast; and if you don't get on, you kind of fall behind, or you are flung off. You know. Part of it is just that narrow path requires you to know things. And to be aware of it. And a lot of people aren't aware of it. They don't know anything about it. They don't know the availability. They don't know the unwritten rules. The other thing is I don't think a lot of people necessarily want that. You know, it's not just who they are. It's not their thing. You know? And one of the things I think about a lot is the stories of kids, kids', teenagers, in my book, who couldn't go all the way to the elite institutions even if they, even if they could cobble together the credentials by high school--you know, their resume by high school to do that. Because of family obligations. You know, there's the young woman in East LA [Los Angeles], who needs to stay in East LA and go to the local community college instead of the more credentialed school because she's her mom's translator. Her mom is Mexican-American, first generation, and like in many families like that, though, the oldest child--in this case the daughter--is the one who kind of deals with both languages. Or, the young boy, African-American boy, in Reno, Nevada, who couldn't leave because his mom is dependent on him for her sobriety. You know, she needs the stability of him. She's now--you know, like 5 years', she's been sober for 5 years and so him and his brother feel they need to stay there with her. And they want to be there with her. So I think, you know, what we ask of people to succeed requires a lot more support than we recognize. A lot more information than we recognize. A lot more understanding of rules that aren't written than we recognize. But also requires wanting this concept, this very, very, this very narrowly defined concept of how to live, and what's important. You know, I say, within the African-American community, the term, you know, 'Acting white,' captures some of that. But, I think the broader term is 'Acting front row.' You have to--you have to behave and think in a certain way to succeed through these institutions. And that's not for everybody. |

| 28:48 | Russ Roberts: Let's talk about the options available to some of these folks. And of course, you are getting a very "biased sample." That doesn't mean it's irrelevant. It's just you are not seeing the people who chose to leave. But the ones who stay, either because they don't want to leave--because they like some aspect of this life or they can't: they can't imagine or know where that path is that could take them out. One of the issues we talk about a lot on the program is the idea that it's gotten harder to leave in America because of the way we've zoned and regulated land use in American cities has driven up rents quite a bit. So, a person from rural Ohio, West Virginia, California, here in Bakersfield--if you want to move to where there's more opportunity, it's a lot more expensive to get there, and stay there. But, you point out--and I think this is hard for us to imagine who are in the front row and had a certain life experience: A lot of the folks you talk to, they don't want to leave. They are happy where they are. They can't imagine leaving. And they are living in places that people in the Front Row would struggle to find bearable. But they are happy; and in an emotional sense they may have some material struggles, but they don't feel they could live anywhere else. Chris Arnade: Right. I think it gets to a larger point that the thing we in the front row only value things we can measure. I call them economic metrics. You know--things that, so you can't really put the value on: the emotional attachment to place. And so we tend to dismiss it. Or ignore it. Or belittle it. When in fact it's one of the few things we gift to people. It doesn't require credentials to have. It just requires being born there. And so, you know, all those, what I call non-credentialed forms of meaning--things that are just kind of just kind of no barriers to entry--like place--other than what is, comes from birth, like place, like family, like faith--we tend to dismiss. I think not necessarily just because we don't believe them, but because we can't measure them. We can't think--we can't really put our hands and grasp, like, what's the importance of knowing that your family has been here three generations and they've all looked to the same hills and they've all walked up the same paths? I think there's a lot of value in that. And a lot of people appreciate that and get a lot out of that. But I think we tend to ignore it, ignore that value, simply because we don't know how to think about it. Russ Roberts: So, I'm going to read an excerpt from the book. You write I was part of a global group of lawyers, bankers, business people, and professors who are their profession first and a New Yorker, Brit, or Southerner second. They are as comfortable in New York City as they are in London or Paris or Sao Paulo or Hong Kong. Well, in the right neighborhoods each.

In their minds, staying put is a mistake. If you stay, you limit your career, you limit your wealth, and you limit your intellectual growth. They also don't fully understand the value of place because like religion, it is hard to measure. What is the value of staying near the family that you raised or in the valley where you were born?

Had I asked those in my hometown when I visited why they stayed, why they were still there, I would have gotten the answer I heard from Cairo, to Amarillo, to rural Ohio. They would have looked at me like I was crazy, and then said, "Because it is my home."

It is an answer that is obvious, because there is value in home, but it isn't just the value of the house or the yard. It is the connection, networks, friends, family, congregation, the Little League team, the usuals at the hairdresser, regulars at the bar, the union hall, the crew at the vape store, the regulars at the half-price movie night, the guys for the Tuesday night basketball.

The front row doesn't fully get that because they don't see that value, and like me, they moved before and will probably move again. We have broken our connections and built new ones. If we can do it, so can anyone else, we think. And then later, you write, you are talking to someone and you say youask him the question I already know the answer to: "Why do you stay here?"

He shoots back without any pause, "Too many ties here, and it is as good a place as you can find."

"Do you like it here?"

"Hell, I was born here. Have to like it. It is home." And I think you nailed something there--you know, I moved six or seven times before I was 8 years old. My high school years were spent outside of Boston, Massachusetts, but we moved when I was a Junior to Israel thinking we were going to stay there. My Dad's company sent him there. We thought we were going to be there for a few years. That was just normal for me. I didn't think anything of moving. I didn't have a place that I would call home except for maybe Memphis where I was born but maybe never really lived, where I had a lot of family. And I think that sense of home for people like me, often highly educated, it is a bit alien for us. And you really, you captured the problem I think some of us have--I've said many times on this program--the problem of poverty is luggage. You know, that people need to get out. And a lot of them don't want to. And that's hard for us to understand.Chris Arnade: Right. It was hard for me to understand. And, again, even then I come from a small town, we were the outsiders in our small town. My dad was a German who had escaped Germany before the War. He was a professor in a town that didn't have any other professors. Or are just a few others. And so me, moving was easy. It was never really my home. Even though I had strong connections and appreciated my town. But, um, so I did the--I leaped from there, to college, to grad school, to New York; and then when I was in New York I was traveling all over the world. So, I would have been a very different guest 20 years before--what I would have basically said just move. And, you know, I should have seen it, because I went home pretty regularly when my parents were alive. And just seen that this is what people wanted. But, you know, you are blind to things you don't want to necessarily think about. Or, it's a hard thing to come to realize. But, you know, I think--again, we just don't understand the value of place. And one of the things that frustrates me is, you are on the Left like I am, you are supposed to, in my mind at least, you are supposed to focus on the working poor. And do, and respect them as much as you respect yourself. And their views. And, you know: Asking them to move is asking them to take away one of the few pieces of capital they have. Or devaluing it. Again, something that's gifted to them at birth. And so you are asking to kind of, that piece of capital has no value. Which is, you know, very elitist. But I would also say, um, at a more pragmatic level--I can put my old Wall Street hat on and say--you are also asking people to sell an asset into probably all-time lows. And so, you are asking them to take that luggage and sell it. Often. And, in a market that might have crashed. Right? Or, so--that's, that's--you are asking them to cash out at a low. So, but, I think the--I don't want to give the impression that a lot of people are that provincial. Since, what you mean, there are people, you can go to one of these towns and a guy will have lived there all his life. You know, also jump in his truck and go work for a month up in North Dakota if there is a job. Right? But they all come back; and he won't move his family. Or, a woman will--I was in Preston, a small town in Kentucky, where I didn't see any black people, except for one. And she was a nurse who had come from Cleveland to work in the hospital for 6 months and was staying in a hotel. So, people do move for temporary employment, but in general there is a lot of value to place. |

| 37:50 | Russ Roberts: So, I want to share my--the tension in my views on this issue of place, and economic change in particular, which is in the background. So, we allow trade mostly, in the United States, free trade. We also allow internal trade. We allow technological change, innovation, that replaces workers with robots and machines and computers. And that leads to a steady, rising standard of living for a lot of people--not every single person at any one moment, of course, but every generation; that's why we're multiple times better off than people who lived, materially, a hundred years ago. But that transition, of course, is hard on certain groups. It was hard on farmers, when we innovated on the farm and changed what size of farm was going to be successful, which meant small farmers basically couldn't persist any more--couldn't pay their loans; their kids, then, couldn't become farmers. There's all kinds of non-material, non-measurable effects of these changes. And, a factory closes, and the opportunities that are created when that factory closes are not in that town any more. That's pretty obvious and visible. What's harder to see are the opportunities that are created elsewhere, for the next generation. So, I'm going to give a negative view of your book, story, and then a positive view. And then I'm going to let you react. So, my negative view, which would be in line with, I would say, the theme of the book, is: By letting, having in place economic policies that allow factories to close, move to Mexico, or become more efficient and hire fewer people, become bigger elsewhere in another location--and this town, which used to be centered around the factory for people who don't have a lot of education to work at--so it's gone. And that means that the social ties that exist in this town start to crumble and tear and disappear. And then, the drugs come; and people have a very hard time. That's the negative story. And your book's a portrait of that despair in the aftermath of some of these economic changes. The positive story would be: Sure, the town does badly; but because we have more resources, because we've tried to be more effective and a lot of people buy things that are less expensive because of trade or technology lowering the costs, new opportunities expand elsewhere. And, we don't see those. They are happening outside the town. And we don't see the kids in that town who leave--who realize this is not where opportunity is any more: it's somewhere else. And, it's much better elsewhere than it was before as a result of the economic change which we set in motion. And so, when we visit the town, which is what you did, what we see are two things: The people who either can't pursue the opportunities elsewhere because they are too old--their training, their skills, their education can't set them on that path--or, they are people who really love where they grew up--those social experiences that you've been poetically and beautifully describing--so they stay. And so, how should I think about those two stories? I mean, I think they are both true. I don't think one is true and one is false. I think they are both true. But, I think in policy circles people--because of the politics--people respond to that with, you know, policy proposals that are--they are very different. So, how do you think about those two stories? Chris Arnade: I think they are both true, as well. I think that the issue, I guess I would say, is: I don't have a--a good part of what I do in my book is I don't give policies, because of the ambiguity of what you just asked, basically. I don't know how to solve the issue. What I would say is, where I think I would differ from you in that description, is: what has been lost--two things. What has been lost is, I think--you know, I used to say, when I kind of make my cartoon summary of how we, how I think about free trade, is kind of [?] removed until we look at a spreadsheet we say, 'Okay. Net--here's a winning column. Here's a losing column. Add them up. It's a positive: let's do it.' As long as it's a positive. 'If it's negative, let's not do it.' I think what I've been trying to say in my book is you are not capturing all the losses. And I think what you're pushing back is you are not capturing all the gains, either. I think, to my point that you are not capturing all the losses: When that factory leaves and those jobs leaves and those young kids who go off to college leave, it leaves a vacuum in the center, where it's not just jobs that are lost but it's families that are taken apart. It's stability that is thrown out the window. It's communities that are emptied of resources and filling, and into that vacuum comes drugs and dysfunction. And despair. Which is why I think you see--unhappiness. And I think is why you see the spike in suicides. Which is just--alone the statistics should give everybody pause. Russ Roberts: No; I agree. Chris Arnade: But, I would say--the other thing I would mention is: When I went to, when I went to--it didn't make it into the book--I went to Lumberton, North Carolina. Which is--it's Robeson County, the poorest county in North Carolina. And I went there partly because a). it was the poorest county, but, b). it's one of the most unique places in the United States, where it's about as diverse as you are going to get. It's one-third African American, one-third white, and one-third Native American--the Lumbee Indians. And they've lost a lot. And when I go to the town, I go to the community college. And I went to the community college in Robeson; it was a summer, so the college was out of session. But, a magnet high school was just finishing up. And that magnet high school had taken the smartest, most talented kids in Robeson County, extracted them from the high school, and given them--at the end, they graduated with a Junior College Degree as well as a college degree--a high school degree. And I sat with about 20 of these kids. And it was a diverse--it was all across a spectrum. It was almost all working class, kids from working class families. A third black, a third white, a third Native American. Just wonderful, wonderful kids. And, to a person, none of them was going to come back. And, you know, I'm not faulting them. I was that kid. I wish I would [?]. And you talk about the winners: Well, they have--they are the ones who are going to win from this new calculation. And, good for them! You know, I don't want to tell them they need to come back to Robeson County and do something they don't want to do. They want to go out and have a life that includes travel-- Russ Roberts: [?] the universe. Chris Arnade: Yeah. And, you know, they are all wonderful kids. But, I however know that had one fifth of them come back to Robeson, they would have changed Robeson for the better. So, I don't know how you change that. I don't think you need to have these 20 kids be forced, you know, be scolded back into coming home. I just think the problem is we have this, this--the difference between those kids--the problem, the solution of it lies is the difference between these kids who leave and the difference between the kids who stay: the reward shouldn't be, the difference in reward shouldn't be as great. You know. You shouldn't be economically rewarded 25 times more if you leave than if you stay. I think that's part of the problem. But also, say, that, there is some sort of inevitability: that we just ultimately throw up our hands and say, 'We can't do anything about this. It's just the way the world goes.' I'm not so sure that's entirely true. I think we've generally accepted it as a culture. Or emphasized economic growth as a primary motive, and done anything and everything to promote it. One of the kind of ways, things I've--there's a small community near my home. I don't know if you've ever heard of the Bruderhofs. They are basically Anti-Baptist Marxists. They are a communal society. They are a commune that is built around the Bible. They were ejected--they were kicked out of Nazi Germany and they resettled in the United States. In any case, they have communal living. They don't own possessions. But the way they make their money is they have a factory. They make children's furniture and furniture of the handicapped. And I had visited the Bruderhof Community because they live near me and invite anybody to come visit. One of the things that is fascinating about their factory was, they actually took technology out of the factory. They have a part of the factory where they manufacture--that they had had automated. And they removed the automation so that the elder members of the community would have a role in the factory. Which, I thought, was a really interesting--fascinating--and they found that it gave a greater sense of health to the community as a whole because everybody had a role in production. I mean, we in many ways have green-lighted change so that it goes forward at an immensely fast pace. The other thing I would say is: I think we think a lot about change--change is good. Which, it is. But I don't think we often think about the pace of change. That humans can only accept so much over such a short period of time. And that, you know, the first derivative of that changes matters a lot. And, it wouldn't be a great [?]--we might have a healthier country in aggregate if we slowed down the pace of change to let things kind of catch up. So, let the kind of communities catch up, to that pace of change. |

| 48:22 | Russ Roberts: Yeah; that's the challenge. And, I don't--we're going to come back and talk about this issue of measurability and the emphasis on growth, because I've come to agree with that view even though I'm still a free market person. I do think our culture and our policies have taken a turn for the worse because of our focus on what is measurable. So, I echo that theme in your book myself, and I'm very sympathetic to it. The challenge is, is, that, you know, how to get there from here. You know, it's one thing to say, '3% growth, 4% growth, we don't need that. 2.6% would be great.' But there isn't a dial. You can't just say, 'We'll accept a little less growth in return for more opportunity for people to react to it.' And, instead, we go, sort of case by case. And we say, for example, we could say, 'We should ban autonomous vehicles. We shouldn't allow them on the roads because they will put 3 million, 4 million, whatever it is, cab drivers, truck drivers out of work, potentially.' Assuming we solve the technological problems--let's say we do. And that's going to be very destructive. It's going to happen overnight. Maybe. Very quickly. It's happening right now. Maybe. And, those people are going to struggle to find work. And it's true that in the long run they'll turn out fine; their kids will have better opportunity--which is the upside of my story as a free marketer. I agree with you that the narrow calculus, 'Well, the benefits outweigh the costs. Let's do it.' That's in economics called Pareto-efficiency, more or less. And I think that's immoral. I reject that utilitarian calculus. I don't think that's the reason to be in favor of economic freedom and allow economic change. I think there are human reasons, not just the net gain in monetary terms to what you can, to the people, within the borders. But, you know, the idea that we can sort of have a less-free market system or a--we have a little less change by dialing back some knob--I think it's a little bit of a--it's a dangerous fantasy. It's going to encourage people's ability to do some very unpalatable things. So, I think the challenge is, given that--I'm not on the Left--but I'm sympathetic to these costs: What kind of ways are there to deal with it? And, unfortunately, to my view, and I suspect to yours, the standard view is: Oh, let's just give them money, for a while. And we had a guest, Jake Vigdor, on the program talking about the minimum wage, where political operatives said, 'Yeah, I'm sure there's going to be a lot of unemployed people because of the living wage in Seattle. But, it doesn't matter. They're going to be unemployed anyway, soon, because of technology. So, what's the difference? They're going to have to get a check anyway, so let's give it to them now.' And I think that it just shows a total lack of what gives people's lives meaning and makes their hearts sing and makes them feel important and dignified--and, lovely. And loved. And I think that whole mindset--which is just as prevalent on the Left and on the Right, shocks me, the more I think about it. It's just not the way to get there from here. It's not the way to solve--'solve' is not the right word--it's not the way to cope with this pace of change. And, I don't think we have a good answer. But, I think a lot of the answers that are on the table now are desperately wrong. Chris Arnade: Yeah. I, um--part of the reason I stay away from policy solutions is: I don't know. I think the problems are too deep. As I say, I think the core problem is not just, we've made everything about the economic, the only form of meaning is the economic and we've forgotten--you know, we've become hyper-utilitarian, to use your language. It's a--people want to feel--at the core, people want to feel a valued member of something larger than themselves. And, you know, a free market-based economy does that for, maybe, the top 5%. Because I can tell you on Wall Street, nobody is happy with their pay. Even if they get paid a lot. They always look at the person next to them and say, 'Oh, they got a lot more than me.' Russ Roberts: That's going to be a tough standard to overcome, the people who are happy with their lot. I like to quote the Talmud. It says, 'Who is rich? The person who is happy with their lot.' That's a rare person. Chris Arnade: That's right. But I think, I think--I guess I would answer your question in another way, which is I happen to believe you have to do income distribution for the short term. Because, I think it's morally right. And I think we argue too much about utility. You've mentioned, you know--why do we always have to put things on a more utilitarian basis? I happen to think we feel the need to always support every argument with data, when I think a lot of the arguments are better just supported by, 'Well, this is morally right.' That's my view on immigration-- Russ Roberts: I agree-- Chris Arnade: I don't--it's the morally right thing to do. End of story. I don't need, I don't need statistics about violence or whatever to support this-- Russ Roberts: [?] rights. Yeah. Chris Arnade: But, getting back to this question: What I feel like--I feel income--free health care is morally right. I think income distribution is morally right. However, if I were, if I were a libertarian or free market person, and I was talking to bankers in a very self-interested way, what I would tell them is--I'd put it in my economic, I'd put it in my math and finance terms, 'You guys need to buy an all-the[?] money put.' Meaning, 'If you do not do something against your philosophy, against your free market philosophy, you are going to have a riot on your hands. And you are going to die.' Heh, heh, heh. You know, not official--you are not going to be killed. But you are going to have a political environment that is going to overthrow you and replace you with something much worse. So, you may not like--it may go against your ideology to do the following 8 things; but in your own self-interest, you'd better do them. Because if you don't, and things progress, continue to progress the way they do, that vacuum I talk about being there, into that vacuum can come ugly, ugly politics. Russ Roberts: Oh, yeah. Yeah. Chris Arnade: And, I view that as kind of like--I agree with you that I don't know the solutions independent of politics, beyond I wish the world in aggregate focused less on material things, and we could think about non-material things and providing people meaning that way. But at a pragmatic level, if something doesn't happen soon, it's going to be ugly. |

| 55:10 | Russ Roberts: So, I disagree with you on a couple of counts, there. Let me push back a little bit, which is that, you know, we do redistribute a non-zero amount of money in the United States. We do have a safety net. The countries that have more generous ones, I'm not sure they have a sustainable path. A world of free health care might be moral, but if it's lousy health care we're not going to like it. And I know there are arguments that say, 'Oh, it's just as good if it's free.' I think that's complicated; but I think that's not our topic today. But I just want to suggest that the "short-run solutions" which either side is pushing are not going to solve the core problem very well. We certainly don't want people starving in the streets. But, this loss of meaning, this loss of connectedness, the loss of dignity, which is what your book is really about, is not solved through material means. And I don't think we've fully--'I don't think'--I know we have not fully come to grips with the transformation of the American family, the change of the pace of economic change that you emphasized a minute ago, which I think is important; and, I think we're going to struggle to figure it out. That's what's on the table. Chris Arnade: I agree with that. I agree that--everything I suggested is band aids. I'll go--I will stand up for free health care. I just think it's--the one thing I can tell--a few times political consultants, whatever, reached out to me based on the findings of my book. I say, 'Look. People, the biggest--the only thing I really hear about every day from people out there is health care, health care, health care, health care.' It's just--it's the political issue that if somebody "solves it," they are going to get elected. But, going back to--I don't know how to fix anything. I mean, that's--I don't know how to do anything beyond band aids. The example I use is: When I was a kid, the town I grew up in, or the town next to what I grew up in, was a classic industrial town. It had two orange juice factories. And, there was a family there that owned the orange juice factory in our, I don't know, their sole owner part of the orange juice factory. And they owned a lot of land. Um, we knew the family was well off. But I went to public high school with the kids. Right? I ended up finding out that the family was somewhere in the Forbes 500, eventually. Which I had no idea. They didn't act like it. They lived as part of the community. That is no longer the case. That--you know-- Russ Roberts: It's rare. Warren Buffett is a rarity. Lives in a "normal house." Chris Arnade: And, I don't know--but this family was part of the community at every level. They didn't, they didn't--you know, they didn't go to Africa to have hunting trips. They just were part of the family community. I don't know how you--I don't know you--you can't legislate that. You know? You can't, through politics create a culture where the people who run the capital--the people who run the markets, who are involved in the markets feel an obligation to the rest of the community, or feel that, you know, the value of the employee weighs more than the market does. I don't know how you enforce that. That just was kind of--it was considered kind of loosh[?louche?] behavior in the past, and people did it less than they do it now. So, I think a lot of it was--again, the people who ran the orange juice factory lived in the town. That orange juice factory was eventually bought by a Brazilian conglomerate and then moved away. So, I think local ownership makes a big difference. You know. I don't have a policy solution of how to change that. Russ Roberts: But I think, I think the solution, ultimately--I think it's a mistake to look for a policy solution. I think that's, you know, that's where the light is, so that's where we look. I think the way this gets solved is the way it unraveled. We're not going to put it back together. The way it unraveled is, to some extent, is that social norms of what's acceptable and unacceptable change. To give your argument its best due. I think there's a lot of truth to that. And, it could change again. People can be ashamed of going to that safari in Africa as a winter break activity rather than proud of it. You can be ashamed owning a $500,000 car rather than not. And, I don't--we don't know how to create culture and norms. So, it's--I recently talked to Mary Hirschfeld about this in an episode about Aquinas and the market. So, it's what we're doing right now: you know, this is a very small step about what we think is admirable versus what is not so admirable. And I think--it's not going to fix anything. But, I think it makes a difference. Chris Arnade: Right. I guess I would say, where I differ from you and where--I mean, where I differ from a lot of people on the Libertarian Right--and I'm not going to just pigeon-hole you in that camp--is: I think the centrality of the market, making the markets central to everything, often, I think it's natural, in point kind of where we are. Which is, you know, as a trader for 30 years, for 20 years, I kind of ended up viewing markets as always ending up in a kind of winner-take-all direction, if they aren't, if they aren't more carefully monitored. I know that's very, very--that's the antithesis of your views. In some ways. But I think the problem is that we've put the market at the center of everything. And, when you do that, that ends up eroding those norms we've talked about. Russ Roberts: But, Chris, who is 'we'? I don't do that, even. And I'm as free market as anybody I think I know-- Chris Arnade: We as a culture. I don't mean-- Russ Roberts: Where does it come from? Who thinks that's a good idea? And where does it manifest itself? In fact, there's so many places where we all agree that it shouldn't become first. That it isn't the only thing. And yet, somehow--I think that's too easy a way to blame where we got to. I think it's so much more complicated. I think the death of the--we say the death of the family like it's already dead. It's close. Chris Arnade: You don't think that some of that, the death of that family, is when we view things only in the material? Thinking that it's only in terms of markets. I mean, look-- Russ Roberts: I don't. But go ahead. Make--tell me why I should. Chris Arnade: No, I'm not--I don't know that I should. I mean, I'm just thinking out loud here. Russ Roberts: Me, too. I don't have an answer. Chris Arnade: I think what frustrates me is, is, I think, I look back at how we put Wall Street central. And I mean, 'we,' mean the elites. In the sense that my party, with Clinton, basically sold out to the--my party sold out to industry and banking, somewhere in the post-Reagan revolution. And I think, when it did that, the sense of the utilitarian dominating everything and then utilitarian giving over to efficiency and GDP growth kind of made, dominated policy for the 20, 25 years. I don't think that had to happen. I think if the Democrats had stayed in opposition to big business, they might have slowed the process down. Now, the other alternative is they might have kept losing and would actually have sped it up. So, you know-- Russ Roberts: But it wasn't a strategic calculation. It was basically I think the incentives on both parties, I think, to coddle Wall Street. And, my joke is: Both parties like to give money to their friends; they just have different friends. They have one friend in common, and that's Wall Street. They both unfortunately take care of it. And it does have terrible costs. And, I think it's been an incredibly destructive 30, 40 years of bailouts and special breaks. And it's horrible. We're on the same page there. Interestingly. |

| 1:04:28 | Russ Roberts: But I think--what I want to suggest on this, this question of "markets"--you know, I don't think there's anything inherently destructive that most Americans, almost all Americans can have a cell phone. Almost all Americans can have inexpensive clothing. Almost all Americans have incredible access to food. These are changes that nobody planned, nobody put in motion through policy. They happened because we let them happen. And most of them have been good. Now, what you are chronicling is the downside. And I think where I will criticize my free market side is saying, my side pretends it doesn't even exist. My side pretends, 'Yeah, everybody is better off.' My side pretends, 'Yeah, it's efficient.' My side pretends, 'Oh, well they'll all find new jobs. The markets are dynamic.' And, your book is a reminder that it's not true. So, I don't want to minimize--not just that. I think what you've chronicled here is deeply important. And, I think this is what, if you are a caring person--and you don't just care about who wins elections or whether your side, your tribal side, is triumphing every 4 years--I think we need to think about these problems in a different way than just, 'Well, they just need a tax break in that neighborhood,' says the free market side. Or, 'Well, they just need more welfare payments,' if you are on the interventionist side. I think that's--we've got to get out of that box. Chris Arnade: I agree with that. And I would say that one of the things I said, one of the smart quips, or one of my quips about 4 years ago on Twitter, what I said was I was about, what I said was, about poke that kind of mentality, what I said was I was maybe, 'Look. My Dad was a historian. My brother is a historian. I recognize by historical standards we're very fortunate.' But I also say is like, maybe people don't want to want two iPhones. Maybe they want one iPhone and three friends. You know? So I think we tend to look at all these problems as, where I think my book has resonated on the Right, even though I'm a Leftist is, the part you are getting to that I'm kind of deflecting. Which is: the book is a lot about--it's not just a material gap that people are experiences--there's a spiritual gap. You know, there's whole, a void there that's just not about things. And as you said, it's pretty clear it's not about things: people have more things now than ever. It's about--and so that's kind of why one of the things I've always said is, one of my frustrations with the Left and Right in this world, both Marxist and Capitalist, is they are two sides of the same coin, where that coin is the material. That's all I think about. One is: how do we have more material stuff, and the other is how do we, you know, redistribute the material stuff we have? And one I think, again, this is why I don't offer policy solutions in my book. Is because it's so much bigger than that. The problem is not--is not the only claim, that's the only claim, that's the only axis we're thinking about. We are not thinking about all the other axes of meaning that are orthogonal to that, face[faith?], place, identity. Those things value people. And I think that's where a lot of the loss is centered. That, because we only think about things we've devalued the spiritual. And I don't mean that only in religious sense, side of the equation-- Russ Roberts: the intangible-- Chris Arnade: The intangible. There you go. And I think that's where the solution is. But I don't know--and this is where I agree with you: There's no policy to get there. You know. Russ Roberts: We'll get there on our own. Because that's what we do. I hope. And I, you'll like this line; I wrote an essay recently on inequality. And I said, you know, there's no, there's no variable, or dignity in the dataset, so we just ignore dignity. And I think-- Chris Arnade: Well, there you go. Russ Roberts: The title of your book, Dignity, is a very appropriate--you could have called it a lot of different things. It's a beautiful title, because that's really what it's about it's about, at the root, that the people you are talking to and photographing, and we didn't tell, mention this, but they are not candid photographs. They are really beautifully posed portraitures of people in these neighborhoods: they are extraordinary, that you took with their permission and their pride and dignity, in tough situations. But, we don't have that variable, so we tend to ignore it. And so the Left and the Right focus on the monetary and material. And that we fight about inequality and how important it is, and how to "fix it" when we ought to be thinking about dignity is I think the central issue of the next few years in our culture and our politics. |

| 1:09:08 | Russ Roberts: But, I want to close with a chapter of your book that we haven't talked about yet, which you take into naturally, which is religion. You spent your Sundays on these tours, in small churches, in very tough neighborhoods. You write beautifully. And I have this image--it almost makes me sweat, just thinking about the folding chairs and the fans--un-air-conditioned. Nothing fancy about these institutions, their storefronts, their beat up buildings. There's a lot of photos in the book. Talk about what you saw in those churches and how it changed you. Chris Arnade: Right. The quip I use is I walked into the Bronx a vegetarian atheist; and now I'm now a meat-eating agnostic who goes to church pretty regularly. Russ Roberts: What do your physics buddies think of them? Chris Arnade: Exactly: what would they think of them? They--I think they try to get where I'm coming from but I think it's not clear. The, the way I think about faith, initially, was--I had to put my scientific hat on, which is, I was seeing, in these communities, like [?] was being used, one of the few places that functioned. And provided people a space, with the churches. And so, it wasn't just a space that provided them dignity, actually. And, not only that, but they accepted them on their terms. There was no barrier to entry. You could just walk in and you found people who were like you. The secular world, cold secular world I'm part of, just provides you dreary institutions that you have to work through like a maze, and that are dehumanizing and have no soul. So, I couldn't deny, initially, the value of religion. Just simply as utilitarian value. And, so, you know, that's where I shifted initially. And then, as I spent more and more time, I realized it wasn't just--you know, this is where I am now: It's pretty arrogant of me to say it as a utilitarian thing, because it's more than that. Maybe. Maybe people are not using in just utilitarian purposes because their situation provides them with an opportunity to understand things better than I understand them. The way I think about it is, I always think about, mathematically, often you learn about a problem: If you want to learn about a problem, you push it to its boundary condition. And things become more clear at the boundary conditions. In many ways what I was seeing was people at their boundary conditions. And, here, faith was essential. And so, maybe, it wasn't just utilitarian. Maybe what they were seeing is was faith as the truth. And it was my situation, and our elites being elite who had everything under control, who was removed from the evidence for faith. So, I started realizing that, you know, there was a lot more going on than I was willing to admit. And it goes back a little bit to that same question we were talking about earlier, about, you kind of dismiss it because you can't measure it. You certainly can't measure faith, in my opinion, so we dismiss it entirely. But I think we are very wrong to do that. |

| 1:13:23 | Russ Roberts: It reminds me of the episode we had with Iain McGilchrist talking about the left side/right side of the brain waves, perceiving the world. And his view, one side, the left side, is very analytical, narrow, narrative-based; easily finds things to fit the narrative. The right side of the brain is more wholistic, humble, less confident, less focused. And, your book, my reading, to some extent, is an application of that--that, coming from the physics, Wall Street background that you grew up in, and were an adult for most of your life, it closed off--he used an example the bird looking with one eye, very carefully at the seed to make sure that you don't pick up a pebble with the seed. With the other eye, connected to the other side of the brain, you are looking for predators. The whole picture is available to you. And so, when you get trained in physics and Wall Street, you are kind of focused on the seed. Heh, heh. And you are now a little more open to the wider range of stuff--not just predators but other stuff. It's really--it's credible honesty. It's brave to write it, on your part. Chris Arnade: You know, I mean, I think, um--yeah, I really said, I think sitting behind a wall of computers, building mathematical models is fun. Believe me, I did it. I still think that way many times for 40 years. But, it's also, I think far more narrow-minded than we do it like to admit. You know. I, I also--I know--I guess the way I frame it to my science friends is, 'Look. I've got a Ph.D. in physics. I understand the Big Bang as well as, I think, a lot of people do. I understand the theory.'-- Russ Roberts: It's a small group. When you say 'a lot of people,' you mean, of the people who understand it. Chris Arnade: Right. I mean, I don't understand it: it's been 20 years. But I can pick up a book and figure it out and remember it. But, the point being, is: I'll say to them, I say, 'Look. Science is great at building bridges. It's not so clear to me it's good at building meaningful lives.' And so, you know, the metaphysical answers that come from science are not any more, any deeper in my mind, than the answers that came before it. It's just a big metaphor, at some level--a mathematical metaphor. But, I think there's a lot to be said--I wish there was a lot more humility within the scientific community, for what we can't know, and what we will never know. And, understanding that. I think the people who are living on the streets who are addicts who have been through a lot not only understand that we are all sinners and that we are all fallible and that we are all need to, we need to embrace the concept of forgiveness--but also, that, there are just things too big to understand. And that we may never understand. And we really don't have this all under control. And, accepting that is really hard for a scientist to do, because we are trained to think with just enough time and enough smarts and enough money we can figure it out. /p> Russ Roberts: You've become a little more skeptical about that. Chris Arnade: Oh, definitely. I would go so far as to say, I'm not so sure--I could get a little more philosophical, but I think there are some things we may just have to accept that we'll never figure out. In that sense, that's where the role of faith is. Russ Roberts: You talked about that in the book. And just now. I'm curious: Let's close with you--you want to say anything about other ways that this experience transformed you? It's a--you know, some people, after 20 years on Wall Street get a really good therapist and are already going to one. You took a very unusual road of therapeutic treatment. I'm sure it changed you in lots of ways. There are other ways you haven't talked about today that this book transformed you. And, do you have any idea of what you are going to do next with your life? Chris Arnade: Um, I'm also-- /p> Russ Roberts: given that new perspective, if I'm right, if you have one [?]? Chris Arnade: The new perspective is, effectively--I mean, to put it in any kind of Power Point presentation form: Data bad; talking to people good. So, the qualitative over the quantitative. But, it also reinforces the view I had to some degree, but now I really truly believe: Before you pass judgment on anybody, or, especially if you pass judgment on a group, walk a mile in their shoes. Or at least walk with them a mile in their shoes. You know, I think we've kind of become--I don't want to use a buzzword or cliché that sounds very political, but we've become, the secularly elite has lost touch with so much. It's not because of bad intentions in my view: I don't want to say that this is just--they are very well intended. That's the frustrating thing. Is: They have the best intentions in mind. But I think that they've become--we--I put myself in that camp--have become so detached from the people we claim to be advocating for. How has it changed me? In different ways, it's made it harder to go to New York City and hang out on Wall Street. It just feels very foreign. It feels like--it just feels so removed from what--you know, and so, in that case, it's very frustrating. Because, it's unfair to the people who are working as bankers[?] now to feel kind of detached and angry at them at some level. It's not their fault. They are good people. I just feel like I want to shake them and say, 'You know, there's this whole part of the country that you guys aren't seeing.' In terms of next projects: The place I feel like I'm most uncomfortable intellectually is that we are talking at the end about faith versus science. And so consequently that's where I want to go next, to spend some time in a small community, kind of just documenting different congregations. And, and not just spending a week or two but spending 6 or 7 months, and trying to understand better the role of faith in our society. |

Photographer, author, and former Wall St. trader Chris Arnade talks about his book, Dignity, with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. Arnade quit his Wall Street trading job and criss-crossed America photographing and getting to know the addicted and homeless who struggle to find work and struggle to survive. The conversation centers on what Arnade learned about Americans and about himself.

Photographer, author, and former Wall St. trader Chris Arnade talks about his book, Dignity, with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. Arnade quit his Wall Street trading job and criss-crossed America photographing and getting to know the addicted and homeless who struggle to find work and struggle to survive. The conversation centers on what Arnade learned about Americans and about himself.

READER COMMENTS

Kevin Ryan

Jul 22 2019 at 12:45pm

This one got increasingly wide-ranging as it progressed. I would like to offer a comment on the relatively narrow subject of migrating away from home for work purposes.

Of course I can understand that many people do not want to move away from their home communities. I am the fortunate son of parents who lived in rural Ireland but came to England (in the late ‘40’s) in order to get work – am talking factories and the building industry here.

They were typical of their siblings and many many others – at the risk of swallowing nostalgic myths, they did not want to leave their communities but they had to, simply because there was no work at home and they needed to work to support themselves and their wider families.

I observe, eg from this podcast but also from many other sources, that now a lot more people are not willing to do this; (and of course there are also many exceptions – the economic migrants). This is perfectly understandable, and in line with evolving expectations and an entitlement philosophy which turn benefits that were previously unimaginable luxuries, including free health care and pensions, into something approaching human rights.

My unimaginative comment then is that I can see this is desirable, but who is going to pay for it?

(I acknowledge that I have only scratched the surface here, and also that the jobs my parents came to England for are now much diminished)

Ajit

Jul 22 2019 at 1:26pm

I found a few things Chris said to be on the border of insulting, even though I know he wasn’t ever meaning to. In this podcast and the previous one, he does a great job of outlining how variable the poor in America are, that a strict generalization of the poor is woefully inadequate. And yet, when he discusses the “front row” – He seemed to to happily generalize. I suspect his view of the front row is representative of the New York City professional – but that is hardly a true representation of the front row. And to say that the front row sneer at the value of cherishing one’s . home and how everything is measured in terms of pure economic benefits is a terrible presumption. For example, I grew up in a well to do suburb of the bay area. Having live in San Francisco and Los Angeles, I still desire to live back where I grew up for all of the reasons Chris has said the working poor do. One can say that I have the luxury of my “town” being in a vibrant economic zone, but that is beside the point – I still value it greatly.

The other issue I have is – he keeps regarding himself as on the left and how the left are the one’s who care about the working poor. That statement then implies that the right does not care about the poor. I will only say that such views are why our political climate is so awful and why political brainwashing has worked so well.

Last thing: I visited the first location of the California gold rush. It was a tourist town filled with vacation homes set aside a picturesque lake. You know what you did not find there? Any of the families of the old gold miners now trapped in despair or drug addiction or boarded up homes. Once the gold dried up, those settlers moved. Unpleasant to be sure, but they did. And I have to think they also liked living there and found it a difficult choice to move. Just as the migrants from mid west moved during the dust bowl. But they did it. What has changed? I have to think government policies that have subsidized the pain of economic competition have made the tradeoff between moving and not moving easier. Is that the world we want?

Joe Moore

Jul 22 2019 at 3:55pm

I observe a strong connection between Dignity and Work.

A century ago most of the population was engaged in securing basic needs, being directly or tangentially involved in food production. Today, technology enables a very small segment of the population to meet this basic need. Technology has facilitated most of life. It just does not take as much Work to sustain our civilization.

To break out of the same old solutions (the left redistributing wealth, the right removing constraints on the market), let our civilization redistribute Work.

Eliminating minimum wage laws (which destroy incentive to hire) and shortening the work week will increase the incentive to hire, especially the marginally productive.

I liked having my gasoline pumped, windshield washed, the oil and tires checked. I liked being ushered in theaters and sporting events. I liked have groceries bagged and carried to my car. Our civilization used to enjoy many jobs of interpersonal service which fostered development of a work ethic and enabled many more people to have a sense of contributing and Dignity.

I agree that Faith also imparts Dignity, but only where it is genuine.

The government can coerce a shorter workweek, and can free us from minimum wage disincentives, but the best it can do little in regard to instilling genuine faith. Possibly it can incentivize institutions to foster its development.

Barry

Aug 8 2019 at 9:20am

I like the way you are thinking on this. I think there is a lot of work not being done, too.

To phrase it the way you do:

I like clean creeks (My kids can’t touch the creek in our neighborhood). I like my lakes not to be overgrown with milfoil. I’d like my kids to be able to walk around town with having to worry about them getting run over.

I bet there are tons of jobs in this that don’t require much beyond a high school education. In a perfect world, how would we make this happen?

Rob

Jul 22 2019 at 7:54pm

I appreciate the longer average episode length recently! Listening to extra EconTalk is better than my next best audio option. Keep it up. 🙂

John Sweetnam

Jul 22 2019 at 10:35pm

This was a wonderful interview and Chris Arnade’s is a remarkable story. Of the many things it caused me to ponder, one was the front row back row and Stephen Harper’s notion of ‘somewheres’ and ‘anywheres’ in his latest book. You know, the one that is not about hockey …

Anyway, Russ has mentioned that some of his interviews come from listener suggestions. Accordingly I recommend the 22nd Prime Minister of Canada – economist, entrepreneur and a great PM.

Andrew Wagner

Jul 23 2019 at 12:38am

I have spent about twenty years working in and around factories and studying them as an engineer, mostly in aerospace.

I think the poor quality of many outsourcing decisions would come as a great surprise to the Wall Street trader and the academic economist. The outsourcing fad that over took most of American industry in late 1990s and 2000s, involved a great deal of social pressure and desire to meet investors expectations rather than hard analysis, and even when analysis was done, it was often deeply flawed.

Some anecdotal examples: an American factory with 30 year old machine tools would be pitted against a Chinese factory with 5 year old machine tools. The American factory had a much deeper experience base, better access to technical talent, shorter transportation distances, and better intellectual property protections, but the American factory, with its aging equipment would be competing with one arm tied behind its back. Recapitalize that factory with similar tooling to the competitor, and given the talented workforce, it would likely be more productive.

Much of the distortion has to do with standard cost accounting methods used by most companies, which assume that costs are directly proportional to direct “hands-on” labor. This assumption was probably true when Donaldson Brown and Alfred Sloan instituted these practices at Dupont and General Motors in the 1920s, when most industrial production was hands-on, but that fundamental assumption–the proportionality of coast to labor, hasn’t been true for decades. Today, one person can operate and maintain half a dozen machine tools, chip foundries, pick & place circuit board machines, etc. Even true manual labor is relieved by automated aides from bar code scanners to computer-controlled projection systems that guide the worker’s hands.

For evidence, we needed look further than the statistics on vehicles with the highest percent content built in the United States: year after year Honda and Toyota top the list. They understand the value of shorter supply chains and local factories. Toyota, in particular, puts an emphasis on people over automation to ensure quality and creativity to drive productivity over time.

One last anecdote: a former employer bought a sub-component from both a local supplier, and an overseas supplier. The cost of those parts included a flat percentage fee that was allocated to absorb the cost of transportation, handling, supplier support–including quality oversight as well as engineering support.

For the overseas supplier, the actual costs were significant: freight across an ocean–air freight expediting when parts were late, weekly long visits by agents and engineers to perform audits and manage contracts (business class was standard for flights of that length), etc..