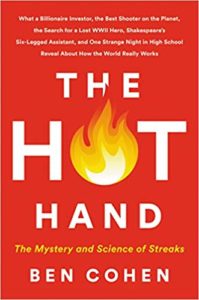

| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: June 30th, 2020.] Russ Roberts: Russ Roberts: Today is June 30th, 2020. My guest is author and journalist, Ben Cohen. He writes about sports for the Wall Street Journal, and he is the author of The Hot Hand: The Mystery and Science of Streaks, and his book is our topic for today. Ben, welcome to EconTalk. Ben Cohen: Thank you for having me. |

| 0:50 | Russ Roberts: What a fascinating book this was. It happens to be something I'm deeply interested in--the question of evaluating whether you can get in a zone, whether you improve performance after you've been successful, or whether that's just a statistical illusion. On one level, it's a book about those things. On another level, it's about a lot more than that--a lot of different aspects of life and art and investing. It's really a fascinating book. And it's a page-turner. Which is pretty impressive. I enjoyed this book thoroughly. There aren't many page-turners about probability and uncertainty. I want to start with an idea of past EconTalk guest Ed Leamer. He says, talking about human beings, 'We are storytelling, pattern-seeking animals.' Now, Nassim Nicholas Taleb says, 'We're easily fooled by randomness.' Actual coin flips--a sequence of actual coin flips--don't often look like we imagined they would look. That's a chunk of your book. Talk about that and our ability to perceive things accurately. Ben Cohen: Well, it's really the reason why there have been hundreds of papers about the hot hand in this field of literature over the last 35 or so years, because the people who first looked into the hot hand and this phenomenon, really did it because they found that we see patterns where they don't exist. And that is why we were so drawn to the hot hand and we all believed in it so fiercely. I mean, this wasn't something that we just thought was true: we all swore it to be true. So, I think that idea of pattern recognition is really central to the hot hand. And, one of the things that was fun to explore in this book is why we believe in patterns. Right? Not just that we do, but what is the explanation? There've been some evolutionary psychologists who have looked into this and found that there were rewards for this in primitive humans; and even monkeys believe in the hot hand. So, this was for foraging; and the world was clumped. Now, the world is less clumped now. I mean, we really live in random environments, and yet this bias of the mind or what we have always thought to be a bias the mind didn't leave us. Right? It was evolutionarily ingrained into us. So, I think this idea of pattern recognition is central to the hot hand and how we think about the hot hand and why it has fooled so many of us and compelled so many of us for such a long time. Russ Roberts: Well, the clumpy thing is interesting. The idea of being that there's something--a productive bush of berries, there might be another one nearby because they're both near a stream, say, and so you don't just look randomly, you look near the stream or you look near the berries that were there, you found yesterday. But, I think it's more than clumpiness. I think it is the really powerful human thirst for causation. We want to see connections between things that A causes B and X causes Y. I think evolutionarily understanding that things are related is a profoundly useful thing. Right? It's really good to understand that. So, I suspect that's part of it as well. Ben Cohen: And the question of course is, are basketball games have clumped? Right? Because, for the last 35 years, there've been hundreds of papers about the hot hand. But, to me, the most interesting ones and the most profound ones were all about basketball. Russ Roberts: Yeah, we should explain what the hot hand is for non-sports fans. So, take a shot at that. Ben Cohen: There's no singular definition, but generally it's the idea of success leading to more success. Now, in basketball, it's when you make one shot and then another shot and then another shot, and you feel more likely to make your next shot. You are in the zone. You're on fire. And, the reason I bring up basketball is not simply because I write about basketball for the Wall Street Journal. It's because all of the major papers about the hot hand over the years have been through the lens of basketball. And so, it would have been intellectually dishonest for me to not write about basketball. The fact that Amos Tversky and Tom Gilovich wrote about basketball 35 years ago was this wonderful excuse for me to write about basketball and use it to explore the rest of the world. Which is really the reason I think why they chose basketball--was because they were not really just writing about basketball. They were writing about judgment and decision-making and how our minds work. Basketball is just this lovely confined[?] environment where you can study decisions with huge stakes and with people incentivized in the same direction. And so, the question is, is basketball clumpy? is it random? is it different from looking at the stream and looking for that shrub with a bunch of berries on it? That's one of the things that, I think, is really interesting to think about. Are our environments more like the streams, or are they more like basketball games? Russ Roberts: But, just to make this a little more clear to the people who have not kept up with the hot hand, I confessed before we started this interview, Ben, that I've been obsessed with it. That's because I have a son who is very analytical and who insisted there is a hot hand. And I would show him the paper showing that there isn't, but he was very adamant about it. So, he feels both redeemed and smarter than his dad. Which is good. Ben Cohen: Well, that's how professional basketball players think. Even when they were given the evidence, they said that, 'This is true. I know this to be true.' |

| 6:34 | Russ Roberts: But what's funny about it--for me, it's the flip side of Moneyball. We've talked about Moneyball in the program, Michael Lewis's book. The Bill James phenomenon--Bill James has been a guest. The idea of Bill James, what's called sabermetrics--the idea of applying statistical analysis to baseball--was to show, not what's the goal, but one of the things it achieved was that it showed that the insiders were often wrong. The scouts would look at a player and say, 'Oh, he's a great prospect.' I've been around the game for a long time and Bill James came along and said, 'Actually, it's not that great a prospect because when you look at what really matters.' And so, a lot of the fun of Moneyball was the idea that the intellectuals, the eggheads, could somehow know more than the insiders. And here's a case where the intellectuals claim to know more than the insiders, were confident they know more than the insiders, but now it looks like the insiders were right all along. Ben Cohen: That's right. But, sort of. I mean, because even if there is such a thing as the hot hand, I think that we can all agree that it is not the fireball from NBA Jam [National Basketball Association Jam] in our imagination. I think we all think that if we make two or three shots in a row, we are guaranteed to make the next shot. And, of course, we're not. I mean, that's one of the things that was so admirable about that classic paper in 1985, which was in-- Russ Roberts: That was in Gilovich/Vallone, is it Vallone? Ben Cohen: Gilovich, Vallone, and Amos Tversky. It's this paper in the canon of Behavioral Economics, and I'm sure your listeners know about. But, what made it so famous was the highly counterintuitive conclusion, which is that there is no such thing as the hot hand. It's simply a matter of seeing patterns and randomness. And, that result held for about 35 years, until it was really kind of called into question over the last three or four years--with work that was just as counterintuitive as that first famous paper. So, one of the things that really appealed to me about this whole saga is that it was deeply contrarian at every turn-- Russ Roberts: It's so satisfying-- Ben Cohen: I mean, that's one of the things that are so delicious about Moneyball is that the contrarians came in and they were right. Well, there are contrarians everywhere you look in the story of the hot hand. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Just to give it a different context for people who aren't basketball fans, if I flip a coin that is, quote, "a fair coin"--meaning it really is going to give us about half heads, half tails over a long series of flips. If I start flipping it and I flip it 100 times in a row, I'm going to get streaks of heads of more than--it's not going to alternate head tail, head, tail, head, tail and be half heads and half tails. There'll be streaks of three and four and five heads in a row, tails in a row, and even maybe streaks of eight or nine. And, if you're not careful, you say, 'Well, this obviously isn't a fair coin.' But, you wouldn't be able to conclude that until you'd flipped it 100 times. Even if you did, the patterns and streaks would still be there. And we are so comfortable with probability that we understand that if I flip a head six times in a row within a long series of 100, I wouldn't want to say, 'Obviously I'm really good at flipping heads,' or 'This must not be a fair coin.' And yet, in basketball, we say all the time that when Steph Curry hit six 3-pointers in a row, we're confident saying, 'See, he's on fire.' Or, 'He's in the zone,' or 'He's really heating up.' And, the question, just to set it in context, is whether that's just no different from the six heads in a row, which we understand is--or the better example, the gambler who bets on black at the roulette wheel and black comes up six times in a row, and he just feels so confident he's going to get the next one right--which is, he's a fool. Ben Cohen: He tells all of his friends about it and buys champagne and goes to a steakhouse that night. Russ Roberts: Yeah. So, the fundamental question is: Can we use statistics and data to tease out whether that streak is a random streak or actually represents something else? And I'm going to push that conversation off toward the end, because it gets technical and it's hard to show without a blackboard a little bit. And we may not get to it, even. Ben Cohen: But, I think what you're hitting at here is that the crucial distinction is to one of control. Right? When we are in control, when we are Steph Curry and the basketball is in our hands, human beings think that we can get hot. That it is not simply the result of chance. But, when we are not in control--when we are at the roulette wheel, for example--we kind of understand that we're at the mercy of chance and we adjust our bets accordingly. It's why, you know, people who follow basketball and play basketball swear that the hot hand is real because they have felt it for themselves, or they have seen it for themselves. And, when you feel it for yourself, as I did--I was a terrible basketball player, but in one quarter of one game in my sophomore year of high school I scored more points than I had in my entire career combined. And, I remember so many details about that day. What is clear to me is that it's really not all that strange. I think we all have that brush, whether it's on the basketball court, whether it's at work, whether it's playing tennis or golf or racquetball or squash or anything. I mean, there are times when we feel that we are transcending ourselves, that we are defining probability. And those times stick with us. They linger with us. Because we think, 'Well, what happened that day?' Like, 'Is there a way for me to predict when this is going to happen or put myself into the zone?' I mean, these are the questions that stick with us. What about you? I assume you've felt this at some points in your life. Russ Roberts: Well, I was just going to say Wade Boggs ate chicken every day before he played baseball, and he did hit, throw over 300 and made the Hall of Fame, so obviously chicken helps. |

| 12:36 | Russ Roberts: For me--I want to make one other comment though, and then I'll give you my own personal take on my hot hand. But, I think this point about control and not control is very important. I think one of the reasons that we like to gamble--and by gamble, I mean, literally go to a casino, I don't mean take risks--one of the reasons we like to go to a casino is it gives us a chance to feel that control, even when it's an illusion. You said we bet accordingly: we know it's not real. I don't think that's really--most often not true. I think we love the idea that we're on fire at the roulette wheel or at the slots or [?]. Even though our head knows that's not true, we're getting a dopamine rush that's equivalent to whatever it was that, when we actually were in a zone, we can do great things. And I think that emotional satisfaction is such a delicious feeling, to use a word you used before. It is exhilarating. And I think that's why people gamble. It's not because, 'Oh, I might make a lot of money.' It's a taste of that when you really aren't in the zone--because it's just random. And you don't care. It's a placebo effect, really. It's a way to get those chemicals flowing in your brain, I think, that flow when you actually achieve something that's real. Ben Cohen: Well, the interesting thing of course, is that the Gambler's Fallacy, in many ways, is the corollary of the hot hand-- Russ Roberts: Explain that. Ben Cohen: So, if you walk into an NBA [National Basketball Association] arena and you see Steph Curry make three shots in a row, everybody in the arena thinks that he's making a fourth shot. And, what's more, everybody in the arena thinks he should take the next shot because he is going to make that shot. Right? But, if you walk into a casino and you go to the roulette wheel and you see the ball land on red three times in a row, what research actually shows is that most people bet on black the next time. So, they bet on the street-- Russ Roberts: It's due[?], it's due[?]. Ben Cohen: they bet on the street to end rather than continue. And when you think about it, the fact that our mind comes to exact opposite conclusions, given the same information--right? three hits in a row--is really fascinating. And that's why I think control is so important. Because we see Steph Curry, we understand that he's sort of in control of his own situation. The defense can adjust, the other coach can call a time out; the situation changes. But the ball is still in his hands. But, you go to a roulette wheel and you know that you have no control over what's going to happen. It's an independent spin. It's a random event. We come to a different conclusion in our mind. These biases are so powerful. I mean, it's the entire reason why Las Vegas exists, right? There are casinos in the desert of the United States because our minds play tricks on us. Russ Roberts: Yeah. And a public policy decision by the State of Nevada. But-- Ben Cohen: That's the advantage of that. |

| 15:18 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. The Steph Curry example is fascinating to me because there's another psychological aspect of this, I think, that's important in the sports following sense, which is: I want to revere him as an athlete. Right? I want him to come through. It's the same reason I wanted LeBron James to win a championship, even though he's not on my team, he's not my guy. I'm a Celtic's fan. But, I was so excited to see his dominance crowned. I thought that was such a beautiful--and to reward the City of Cleveland was, it was part of it, too. So, when Curry takes that fourth shot and I'm so excited for it to go in and I'm going to get a huge dopamine rush if I am a Golden State Warriors fan, I'm not so stupid to feel that way about the roulette wheel. I'm not going to say, 'Well, this is that roulette wheel, it's so good at red.' Now, I may occasionally fall into that streak for a different emotional--well, I'll say, but I think when it's a human being, we're rooting for them, just sometimes we root for them to fail. We want them to be-- Ben Cohen: But also, but, if you think about the way that Las Vegas works, they encourage you to chase these patterns. Right? They want you to think, 'Oh.' Like, you go to a roulette wheel in any of the big casinos in Las Vegas-- Russ Roberts: They post it, you told me, you wrote about it-- Ben Cohen: They post the last 20 numbers, and they post the breakdown of black versus red. They want you to see eight reds in a row and then bet on black the next time. I mean, it has no effect-- Russ Roberts: Or the other way -- Ben Cohen: on what could happen. Exactly. Russ Roberts: Or the other way. They want you to think you're a master of it. You can-- Ben Cohen: They want to overload you with information. Right? But, to me, what's so interesting, you're talking about revering Steph Curry or LeBron James. The interesting thing to me about basketball--of course, the idea of whether or not you can get hot, whether or not that's real or whether it's a fallacy is interesting. But, the power of the hot hand was really interesting to me. The fact that--I make an argument, anyway, and I think it's true that one hot game, the hottest game of Steph Curry's life really changed everything for him. And it changed the fate of the Golden State Warriors and the future of the entire NBA-- Russ Roberts: It changed basketball. Ben Cohen: The whole sport. Right? I mean, the sport is not the same. Now, you could argue that the sport was going that way anyway and that this was only a matter of time. But, Steph Curry's scoring 54 points in Madison Square Garden, taking and making the most 3-pointers of his life, and doing all this at sort of an inflection three point of his career, and then looking around and everybody realizing, 'Maybe we should let the greatest shooter in the history of the planet shoot a little bit more.' It's so interesting to me that there was a real point in his career and it's the hottest game that he ever had. And the fact that--I'd love to tell the story of how it all happened. I mean, there was no way for him to predict that that was going to be the game that he got hot. It was a game in February 2013 against the Knicks. If you were to ask him five minutes before the game, 'Is this a game that you are going to play well, let alone play better than you ever have in your life?' he would have looked at you like you had eight heads, because everything had gone wrong for him that day. Russ Roberts: When the bus got pulled over for-- Ben Cohen: He missed the bus he usually takes; he wakes up $35,000 poorer from getting in a fight the night before. The bus that he ends up on gets pulled over on the way to Madison Square Garden by New York City traffic cops. So, he's late, he's rushed, he's probably in a bad mood because he has to give $35,000 to the NBA. And, then he goes out and he has the game of his life. Is there any way to predict that? No, of course. Russ Roberts: But, the other point I think I want to make--and then we'll move on to some of the other applications; so, the non-basketball fans sit tight, we're getting there--is that, if you have seen a game like that, if you've seen an athlete in their prime who has an extraordinary night, of course, it could just be random. But the part that actually separates it from randomness, I think is alluded to in one of the studies that you talk about in the book, which is that when a person feels they're in that zone, they're not taking a random selection of three pointers. I mean, if you're a basketball fan in the last five years, you've seen Steph Curry pull up five, eight, maybe 10 feet behind the three-point line. And it's nothing but net; and the crowd--he feels--by the way, when he releases the ball, and you can see this with Larry Bird, one of my favorite sports videos of all time is of the three-point shooting contest at the All-Star Game. Larry Bird needs to make one more shot to win the contest. He's got time to take two or three more, but he releases the winning shot and walks off the court while the ball is the air with his finger up, saying, 'I'm number one,' or pointing to heaven or whatever he was doing. And he knows it's going in, and he knew it was going in when he released it. It's just a feeling. Russ Roberts: And you could argue that feeling is an illusion: it could be. But, the point is, they're not a random sample of shots. They get harder and harder because the opposition feels the same thing that we're talking about, and they try to adjust as you point out. And the fact that they still keep going in is not easily tested by the proportion of makes after a certain set of string of makes because the shots should be a lower percentage shot than they were before. Ben Cohen: That's right. The hot hand works the behavior of everybody on the court, not just the shooter, but the defense and the teammates and fans and coaches--everybody. So, for Steph Curry to take a shot when he's hot and to turn around knowing it's going in, think about that. Larry Bird is doing it in a three point contest with no defender. Steph Curry is doing it with nine people on the court who were the best player on every team that they had ever been on until getting to that court. Right? I mean, it's really astonishing. It really does raise the question of: how much should we believe experts and professionals when they say this is real? Steph Curry has taken tens of millions of shots over the course of his life and he says that what is happening in those moments is different. Should we believe him or should we think it's just chance? And I think that the really lovely and wonderful thing about the hot hand is that there were really smart people on both sides of this debate. And, it's perfectly fine to think there is no such thing as the hot hand; or, of course, there is such a thing as the hot hand; or, probably the truth is somewhere in between. And I think the fun of this is sort of playing around with that idea and toying around with it and seeing where you land for yourself. Because, what you think in one environment might be the opposite of what you think in another environment. Russ Roberts: Right. You might think there is a hot hand in basketball, but not somewhere else, not in some other human endeavor. I want to say one last thing about basketball--I apologize to the non-basketball fans--but there's an interesting relationship potentially between this phenomenon and what is called 'trash talking' in sports. When Larry Bird showed up for that-- Ben Cohen: That's the psychological definition of it--trash talking is the name of it. Russ Roberts: What? Yeah. That's the technical term. That's the jargon. So, in the locker room before that three-point shooting contest--well, again, the players who were hanging around, they're not just a random sample, they're best basketball shooters in the world; there's eight of them there. And Larry Bird allegedly said, and I'm sure it's true, 'Who's finishing second?' And, that was a way, I think, to intimidate them, but also to convince himself that tonight, he's going to have the hot hand. It's a way of--who knows what works on our psyches and our adrenaline or emotions to help us achieve beyond our average or normal? Ben Cohen: Of course, there's a factor of confidence here. When you get hot, you feel like you have license to take harder shots and crazier shots, riskier shot, shots that would ordinarily earn you a spot on the end of the bench. And you have to have that confidence if you are an NBA player. And, one of the things that I would love, I'm not writing a sequel to this book, but I feel like a very fun follow-up study would be to strap electrodes into the brains of players. Right? To do an MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] study of seeing what's actually happening in your brain, to your brain chemistry, when you get hot. Because, we know the players believe this and that they chase out this sort of behavior. But it would be really interesting to know, like, exactly the neurons that are firing and when and why they happen. I do think this field of research is only getting started and that's one thing I'd really love to see add to this literature about the hot hand. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I thought you were going to say you're not going to write a follow up, but if you did, it be called "The Cold Hand." When-- Ben Cohen: That would just be depressing, though-- Russ Roberts: when Shaquille O'Neal misses his fourth or fifth free throw in a row, does the sixth get even less likely? I think it probably does. But that-- Ben Cohen: For the same reason, right? Russ Roberts: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Absolutely. But, I think the challenge in thinking about this carefully, which is really incredibly difficult, is that, there's a difference between--the reason that Steph Curry's story of his 54 points is so intriguing is that he was in a lousy the mood, he probably didn't sleep well the night before. Sometimes, quote, "the hot hand" is just: you're performing at peak performance. It's not so much, 'Oh, you made one and that makes you more confident. You feel like you're in the zone.' Sometimes you have some really good nights. And I think it's hard to distinguish. |

| 24:24 | Russ Roberts: Well, let's turn to Shakespeare. Let me mention Shakespeare, which you talk about beautifully in the book, and apply this question about performance. So, Shakespeare has a really good year in, I think, 1605, right? He publishes--he writes King Lear, MacBeth, and Antony and Cleopatra. Did he have the hot hand? Or was he just getting a lot of good sleep those 12 months? They're two different things--to me--even though they're kind of the same. Ben Cohen: So, to me, Shakespeare and Steph Curry actually have a whole lot in common, mostly because neither one of them would have predicted that it's the hottest stretch of their career what[?] had happened the way it did. Because, what changed in 1605 and 1606 that allowed Shakespeare to get hot, it was not just Shakespeare: it was the world around him. What changed is that it was a plague year. The plague was sort of Shakespeare's secret weapon, in many ways. The plague was this constant force in Shakespeare's life, which I didn't realize until writing this book. I mean, he probably should have died from plague when he was an infant. His parents had already lost children to the plague when the plagues swept through Stratford-upon-Avon when he was very, very young, and it killed sort of indiscriminately. So, the fact that he lived was a matter of chance. He baked the plague into Romeo and Juliet. I mean, the plague is really what turns the most famous love story ever into a tragedy, which, I'm sort of embarrassed to admit that I did not realize when I read the play in eighth grade and I did not realize when I majored in English in college--one of those faults is probably much worse than the other. And, then, the plague is what allows him to get hot in 1605 and 1606--for many reasons. It puts theater-goers into a state of mind where they want to see his plays again. It closes certain playhouses. In a very macabre way, it sort of kills off his competition a little bit. But, he is able to take advantage of these very unlikely circumstances. And so, I didn't have a chance to ask Shakespeare about this, but I did ask Steph Curry about it. I said, 'Do you have any idea of when you are going to get hot?' And what he said is that he doesn't know why, or how, or when, or where it's going to happen; but once it does happen, you have to embrace it. And I think Shakespeare would probably say the same thing, maybe in a more eloquent way, or a longer way. But, you never quite know when the circumstances are going to arise: but the best thing you can do is just try to take advantage, even if it's a plague year. |

| 26:56 | Russ Roberts: So, let's digress for a minute, just because it's too much fun to talk about Romeo and Juliet, which--spoiler alert, if you haven't seen it or you don't know how it ends. Ben, come on. So, it's not a happy ending. Shakespeare wrote comedies, tragedies, histories--I think are the three main categories. This isn't the tragedy kind. I recently saw Shakespeare in Love for the second or third time, which is one of my top 10 favorite movies ever. It's an extraordinarily fabulous movie where Tom Stoppard--my favorite living playwright, wrote a good chunk of the screenplay, where he co-wrote it; I don't know how much of it is his. But, it's funny and witty and brilliant, sad and moving and fun. And, it's just a great movie. And one of the reasons that's a great movie--to me--is that we see Romeo and Juliet performed for the first time. And, we don't--we forget that when it was performed the first time, nobody knew how it ended. So, when Juliet takes a potion that's going to put her to sleep, and make her look like she's dead, Romeo finds her, thinks she is dead, kills himself. She wakes up, sees that he's dead and kills herself instead of them being reunited. And that's the spoiler alert. And when the crowd sees this on stage first time, the gasp of shock and horror and realization of how this is going to turn after they're all wanting it to go a different directions, it's so--it's so powerful. Ben Cohen: It's so interesting, though, because when she does take the potion, you could easily see it becoming a comedy, right? Where-- Russ Roberts: Correct-- Ben Cohen: where they have this crazy twist that leads to them running away-- Russ Roberts: Yeah, run off to Rio, start a new life. Yeah, it's going to be great. But, what I didn't realize, which I learned from your book because I also was a bad reader, is that that plot twist that he doesn't know that she's faking the potion and that it's a coma, not death, and she's going to wake up, he was supposed to get a message about that. And the reason he doesn't get the message is? Tell us. Ben Cohen: Because the messenger who is sent gets stuck in quarantine. Which, you know, I have to say, I wrote this book over the last two or or three years. I did not anticipate a pandemic-- Russ Roberts: So, COVID-- Ben Cohen: but it came out the day before, you know, basically the whole country found itself in quarantine. And so, the reason why Shakespeare--sorry, not Shakespeare. The reason why Romeo doesn't know that Juliet has taken this potion and that she is simply sleeping and not actually dead is because this whole harebrained scheme had not been explained to him because he never gets the letter. So, if you think about it, it's really a bonkers plot line. The flyer says, 'I will--Juliet, take this sleeping potion, it will knock you out. Your family will think you're dead. When they think you're dead, Romeo is going to come back and he's going to sweep you away and take you and live happily ever after.' Now, this is the stuff that like you wouldn't even see on a reality show or some terrible soap opera now. And yet, it's our most famous love story. And so, why does it fall apart? She takes the sleeping potion, right? She gets knocked out. Her family thinks she's dead. Romeo comes back and sees her in the open crypt. All of the crazy stuff actually turns out--where the whole scheme falls apart--is simply on getting a letter to Romeo. And it falls apart because the plague is sweeping through and the messenger gets stuck in quarantine. So, all of this is the plague. Russ Roberts: And, as you point out, which I thought was a brilliant insight--it's four lines where the guy says to the other guy, 'Oh, did you get that message to Romeo?' 'Oh, no I couldn't get it to him. Sorry.' Ben Cohen: But, the subtext was so clear back then-- Russ Roberts: Correct. Ben Cohen: You don't hit the audience over the head. Now, 400 years later, you kind of do, right? I think I write in the book that it's the same as if someone now were to tweet something and end it with sad-explanation point. We all know what that's a reference to. But, if someone is reading that tweet 400 years from now, God forbid, they might not understand that we are making an allusion to the way that the President of the United States tweets-- Russ Roberts: Tweets. Ben Cohen: And so nobody in the theater would have wanted to hear about the plague. It's like being on a cruise ship and watching Titanic. I mean, you understand the risk and you don't want to think about that. But they all understood what was happening. We just don't understand what was happening, now. Russ Roberts: Yeah, but now we do. Although it's in Shakespearean-- Ben Cohen: And of course it's like basically written in a different language if you're in eighth grade. I mean, it's like reading Aeschylus in the original Greek. Of course, you don't understand it. It's not written for you to be understood and it's sort of written in a different language. Russ Roberts: And I don't think any less of you, I really don't, after that eighth grade failure. But, you should have noticed it, sorry-- Ben Cohen: I should have noticed. I have to say, I feel really--I'm just going to bury my English degree because I did take Shakespeare courses in college and I did not even realize it was[?] happening. Russ Roberts: But, I think that point, which is so fabulous that you don't need a two-page, 10-minute dialogue about the letter not getting there, because everybody in the crowd has experienced horrible things because of the quarantine--they all are very aware of it. And so, this is just a standard real life plausible thing. Looking back on it before this COVID tragedy, we would have said, 'Oh, that's weird. Why didn't he make it clearer?' Because: they didn't need to then. Ben Cohen: Or, why didn't the messengers just leave the quarantine house? Right? Could it really have been that bad? And yet, that scene now feels oddly resonant in the same way that people in 1606 would have understood: of course he's not leaving the quarantined house. I mean, we all understand that now. Like, yeah: you're not going out to deliver a letter to somebody. Russ Roberts: And it was a lot--the masks of 1605 weren't nearly as good and-- Ben Cohen: Yeah, they weren't any in '94s then, they were made in '95. Russ Roberts: Correct, '93, '92. And, then plus that plague--that was a plague, and it was a lot worse. |

| 32:57 | Russ Roberts: Let's--you talk about asylum judges, which it seems like a large leap, but it's not. But, when you were talking about that, I actually had the same thought you were going to eventually come to in that story. So, talk about asylum judges and what that might have to do with the hot hand or streaks, anyway. Ben Cohen: There was this brilliant paper a couple of years ago by Toby Moscowitz and a couple of his economist colleagues where they looked at decision-making for loan officers and baseball umpires and asylum judges. So, people who are entrusted to be authorities to make important-- Russ Roberts: Arbiters-- Ben Cohen: decisions. Yeah, exactly. And so, in baseball anyway, there's a phenomenon where if an umpire calls two close strikes in a row, he is much less likely to call the next close pitch a strike. Right? He is trying to even out the streak in his own mind. And, there's incredible data in sports now, and especially in baseball. And they were able to look at millions of pitches and actually look at the precise location of these pitches and show that baseball umpires are prone to making decisions under the Gambler's Fallacy, where they try to adjust for those streaks in their own minds. And, that is a trivial example. Of course, there are billions of dollars on the line in a baseball game; but really we're talking about calling balls and strikes. But, it's not so trivial when you take that phenomenon and you apply it to an asylum court. What they've found is that if an asylum judge has granted asylum to two or three refugees in a row, he is much less likely to grant asylum to the next case, regardless of the merits of the case. Now, that's crushing, that's a depressing number. That's not calling balls and strikes. That's deciding whether or not someone stays in the United States, and really it's deciding whether or not they live or they die. The fact that people whose jobs it is to make informed decisions, judgements--they are judges--can be prone to such a bias of the mind, I think, is a really powerful example, and it shows the human consequences of the hot hand and the gambler's fallacy. It's not just about basketball or it's not just about baseball. You have a life in your hand when you are deciding whether or not they deserve asylum in the United States. You know, in the book, I write about an Iraqi sculptor who applied for asylum whose case gets derailed for a whole bunch of different reasons, in part because there's an incredible backlog right now that the asylum system has really failed in the United States. But, once he does get into the court, it was just sort of stunning to me that it almost doesn't matter why he wants to be in the United States or where he is seeing a judge or which judge he is seeing: it's a matter of which cases have been heard directly before him. It really is more like a roulette wheel than anything else--which, you don't want the asylum court to operate like a casino, but in many ways it actually does. Russ Roberts: Yeah. I'm a little bit skeptical that [?] finally had I looked at that paper, it all--I heard about it from you. One thing that struck me about it was how small the effect is. I think it was two percentage points, three percentage point, something like that? And, the odds, to me, that you could tease that out, given the complexity of each case, then you're going to pretend you're controlling for it. But, having said that--so, having said that, expressed my skepticism as a grader of papers--and you actually ended up talking about that because when you were writing about the judging, I was thinking, when I graded essay kind of answers where there's no clear right or wrong answer and I'm trying to tease out the quality of the intuition and the argument, I wonder how susceptible I was to the order of papers that I received. If you have a lot of really bad ones in a row that you gave bad grades. So it's not so much, 'I need to pull up the average.' It's more like, 'Boy, this is a breath of fresh air,' and you over-reward that paper. So, I think streakiness does affect judges, inevitably, as human beings. Ben Cohen: Well, look at the opposite of that. If you just read[?] two or three A+ papers in a row, what might be an A paper suddenly reads a B+ paper. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Right. Again, to make a confession, one of the reasons I left the classroom as a teacher was that I hated grading. And it's not because it's tedious. It's because it's unjust. There's an inevitable subjectivity. And, at the end of a long night--I used to grade all my own exams; and they were not, again, not multiple choice, they were--I have a great amount of exams when I taught 300-and-something people--I think there were 390 people at UCLA--because I felt that was important. And, then I'd realized after I graded seven or eight in a row, I'm thinking: I'm going to go back and look at those seven and eight and see if I need to make an adjustment based on--I would start doing that. And, then you realize, 'boy, there's an arbitrary anus to this that's awful. And, I think short essay questions often in economics relating to problems and puzzles are the right way to test whether somebody understands it, but assessing those precisely with an A through F scheme is pretty tough. Ben Cohen: So, Toby Moskowitz, one of the authors of this paper, thought about this exact problem. He instituted something of a solution in his own life. He made a behavioral tweak after studying this issue. And what he does now is, when he assigns exams and papers to his teaching assistants [TAs] to grade, instead of simply giving them to the TA and saying. 'Just grade these papers in order,' what he does is, he gives them the stack of papers and he shuffles the order in which they see them. So, they are not simply seeing the three A+ papers and then being asked to grade another paper. They're seeing them in an entirely different order. And what he does is he averages the grades of those papers--which is not a perfect solution, but it's pretty good. It reduces the bias, this particular bias. Now, it would be great if we could do that with an asylum system, right? Or, for an umpire who is making balls and strikes calls. We can't. I mean, this is real life, and we have to take in other factors. But, it is interesting that you can sort of make these tweaks in your own life. Really, I think it's important to just think about them. I mean, you were clearly aware of it and it made you realize that the unfairness of the system. I think we can all make our own judgments and decisions from there. But, it's important to be aware of them, I think and try to figure out what we can do to make this a fairer world and reduce that bias in our own lives. Because, I think that this does affect all of us in different ways, even if we are not playing basketball or going to a casino or grading 390 economics exams. Russ Roberts: Yeah, I don't know what I was thinking back then. I was young. I was staying up late. |

| 40:10 | Russ Roberts: You asked me, by the way, about my own personal experiences. I'm going to flip that back on to you. You had a great moment in eighth grade, or--was it 8th grade basketball? Ben Cohen: Uh, 10th grade. Russ Roberts: Sophomore year, sorry. Yeah. Ben Cohen: Insulting me like that! Russ Roberts: Eighth grade English--that's where you fell down and you missed Romeo and Juliet. You didn't understand that Hamlet was about it a beleaguered prince. You had a lot of bad things in a row there. More seriously: For me, the hot hand for me is as a writer. There are times when I just know that I'm going to write well and I'm in that zone and I try to write a lot in that time. And when I'm not, it doesn't bother me that I'm not writing so much because I know it's not as good. So, I don't know whether, again, it's each successful thing builds on itself or whether it's just I'm in an effective place versus a less effective place? But, I would say as a writer, in particular writing poetry, if I come up with a good line of poetry, I feel like I could just create the next verse and it's all going to flow. It's a matter of--you talk about flow, actually, in the book as part of that same phenomenon. Do you feel that as a writer? Ben Cohen: Very, very, very occasionally, and I wish that I felt it more. There have been a couple of stories that I've been on in which I have felt hot in which people are calling me back and stories are flowing and success begets success. And I think that's actually pretty common in journalism. But, the one thing that I always try to remind myself in those very rare occasions when I feel hot is that this is the time to work hard and to go to sleep late and to wake up early, because there's nothing worse than when the hot hand runs out. And, the one thing that we do know about the hot hand is that it does not last forever. So, we try to bottle that magical feeling for as long as we can. Can I ask you: Are you ever able to predict when you are going to be in the zone writing poetry? And, when you are, do you do anything to try to elongate that period of being hot? Russ Roberts: I don't know when it's going to happen. One of the things I used to do--I don't do it as much as I used to--is that I listened to a certain kind of music. When I was younger, just the way it was for me, I'd listen to Irish music instrumental--Gaelic Storm, Layhe, Great Big C. Groups that, they're not Irish, but there's a relationship. Music that's driving and exhilarating. And I found out later that Stephen King does the same thing. Stephen King listens to rock music while he writes, which is--I'd tell that to my dad; he'd say, 'I can't do anything while I'm writing. I have to have total silence. But, for me, it's a brain trick, and it gets my--I don't know how it works obviously; nobody does probably. But, it is a way that I can turbocharge that feeling. Just one other thing about writing, I think is interesting. Hemingway wrote an amusing essay about a young writer who comes to visit him and asks him for advice. He's a pest. Hemingway doesn't want to spend time with him. But he takes him fishing and he records their conversation--not literally, but he writes about their conversation. And one of the things Hemingway said that's always stuck with me is, he says, 'Stop writing when you know what's going to happen next.' Because if you finish a plot line or a section of an argument, and then you come back to it and you have to start from scratch, sometimes you just can't get the engine going. Whereas, you can sort of tap into that. I don't know if it's flow or whatever you want to call it, that process that--it's like an amusement park ride when it goes well. It's just, 'I'm going to get back in the car and go around. I'm going to go around again.' Ben Cohen: Of course, it's like, it's leaving being parked downhill so you can gather momentum-- Russ Roberts: Great example-- Ben Cohen: when you [inaudible 00:44:12] the computer the next day. I sort of did that while writing this book. I wish that I had gotten hot while writing this book: it would have been a lot easier to write. But, there were times when I would limit myself to a certain number of words per day, knowing that I hit a certain mark and I kind of left myself the next section to start knowing where it was going to be. So, I was not simply looking at a blank page: I was looking at a blank page with an idea of how to fill it. And, that kind of helped me. It sort of gave me a regimen, a routine, rather than just coming to a computer every morning and saying, 'I wonder what's going to happen today.' Russ Roberts: 'What now?' Yeah. I'm surprised--that's the way you described your own writing, what you said before about, that it's only occasional for you. The book is filled with interesting stories. They're all about the hot hand in various dimensions and guises. Some of them, I found more convincing than others as being hot hand versus just something like a streak. But they're not quite the same. But it didn't matter. I enjoyed every one of them, Ben. You're such a good storyteller and such a good writer. I guess, if I could compliment--now that I've insulted you before about Romeo and Juliet--kind of like Flaubert. Flaubert would evidently write--he would agonize over a sentence for a day until it was perfect, and then he'd move on. It looks like you just kind of breeze along. Ben Cohen: Well, I'm glad that it comes off that way. And that's a very lovely compliment and I very much appreciate it. No, it's a--one of the things that I thought while writing this book is that, there are stories in here that you might read and say, 'Nah, I don't really think that works.' But, hopefully, it will be such a fun experience reading the stories along the way that you won't regret it. |

| 46:00 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. Like I said, I enjoyed every one of them. I mean, there's stuff in this book about Van Gogh; about Raoul Wallenberg and the Holocaust; David Booth and Rick [?] in the Index Mutual Fund. We should talk about that a little bit. This is called the EconTalk, and people do think economics has something to do with investing. Not so much. But, this is one of the parts where it actually, economics has something to say about it, I think. I used to think about this a lot because there was a mutual fund--I'm going to get it wrong, so I apologize to listeners--but I think it was PIMCO [Pacific Investment Management Company] that beat the market every year for, I think 17 years. And I'd say, 'Well, maybe it's just lucky.' And people would think I was an idiot. Because, 'Obviously, it's not lucky, 17 heads in a row.' But of course, if you have thousands of people picking stocks, you'd expect there'd be one--well, 17 might be a bit large--but you do expect long streaks that might be purely random. And so, in investing, I think there is an enormous temptation, unlike the casino, to think that you know what's going on and you're really good at it. Ben Cohen: Absolutely. Yeah. And, in fact, when I had lunch with David Booth a couple of years ago, he said, 'In many ways, the fundamental question of investing and stock-picking is: Is there such a thing as the hot hand?' And, he was one of the first people to say no, and to make a huge bet on it. And he became fabulously wealthy based on the strength of that idea. Right? I mean, he sort of was one of the pioneers of index funds; and he did it at a time when it was a deeply unsexy approach to investing--and again, contrarian. I mean, there is sort of, everywhere you look in this idea, the hot hand. And, you know, I could have written about any number of these fund managers. Right? I mean, there are plenty of people who claim to be hot or know where the market is going, or have a track record of doing that. But, the reason why I was so drawn to David Booth is because, again, he has a history in basketball. David Booth grew up on Naismith Drive in Lawrence, Kansas, named after James Naismith, the inventor of basketball. And, how did he spend some of his fortune? One of the first lavish purchases that he made was at an auction a couple of years ago when he spent about $3.5 million to buy the original rules of basketball as written by James Naismith himself. And he donated them back to Kansas University where he went to school and where he grew up a half a mile away. So, the really wonderful thing about-- Russ Roberts: That was so fun-- Ben Cohen: this story is that he believes in the hot hand in basketball. He sits courtside at Jayhawk games. He has seen it for himself. He has felt it for himself. And yet he has made billions of dollars by not behaving as if he believes in the hot hand in his own field. Right? And so, I just found that such a wonderful contradiction. And it sort of shows that you might be a farmer--for example, in the book, I go to the border of Minnesota in North Dakota and I write about a sugar beet farmer who also believes in the hot hand in basketball and in other parts of his life. But, he understands that in his industry, in his environment where he is really at the mercy of chance and something as random as the weather, if he bets the farm on believing in the hot hand, he can lose everything. Russ Roberts: What is 'bets the'--oh, you're so--shame on you, Ben. That's a good line, good line. No, that was fantastic. I think, when you step back philosophically and think about the significance of the book for daily life, beyond investing in basketball, etc., is what you alluded to earlier: Being aware of your awareness or lack of awareness about these phenomena in your life is useful. It's helpful, I think, to think about how we often overemphasize what we have control over and think we're good at something, how often we--when it's life or death--often are going to, like in the case of a farmer, be very aware that we're not going to have an extra good year. 'So, I don't have to set aside any corn for next year because I'm on a roll. I'm really good at farming now.' People who do that, don't stay in farming: they get wiped out and they leave. Ben Cohen: That's right. I mean, farmers understand you have to play the long game. The farmer that I write about, Nick Hagan, his family has owned this piece of land for 150 years. He is a fifth generation sugar beet farmer. And, the lessons of his great, great grandfather who came over from a different country, still apply to him in 2020. The way he put it, I thought it was really interesting. He said, 'Farming is defense.' If you are Steph Curry, you are playing defense, the ball is in your hand. But, when you're a farmer, you control almost nothing. You can only control what you can control. And so, if soybeans have two or three good years, you can't drop everything and invest everything you have into soybeans hoping that they have another good year or you'll lose everything. And so, to him, playing the long game and playing defense and always expecting the worst and hoping for anything better is really important. And, I just thought Nick was such a fascinating character because not only is he a sports nut, but he's a Julliard-trained trombonist. When he was in music, everything he was trying to do was to emphasize plan A. Because, if you want to be playing in Carnegie Hall, you have to practice eight hours a day and you have to do everything you can. You really have control of your own situation. Farming is the exact opposite. And it took him a few years once he returned to East Grand Forks, Minnesota to get used to that. But, he did; and he was able to have both ideas in his own mind. And I really love that. Russ Roberts: I once had heard Herb Kelleher, the founder of Southwest Airlines, talk about his business. I was teaching at the Olin School of Business at Washington University in St. Louis, and I used to go to these events where CEOs [Chief Executive Officers] would talk about how smart they were and pretend it was just all their employees. Just one story from there--he showed up for that talk--well, two stories, maybe three. He shows up for that talk in a car driven by one of his employees--not in a limo, not in a fancy car. There were, like, six people crammed into the car because they all wanted to ride with Herb. But, when he gets to the talk, one of the first things he said was, 'I want to thank all my employees. Without them, we would have nothing.' And, I've heard that a thousand times from these people; it's false modesty, usually. I find it a big turnoff. But I happened to look at the faces. And he said, 'A number of them are here today, I'd like them to stand.' And, 20, 30 people popped up--there were 800 people probably in that room, and 20 or 30 of them popped up. They were Southwest employees who come out to hear their boss. And, they were beaming. They were so proud to be a part of that company. This is a long time ago and I don't know how the morale is doing since then. But, anyway, in the Q&A [Questions and Answers], they asked him, 'How do you make money every year in a business that most people lose money half the time or more?' And he said, 'Oh, I always remember that the bad times will come.' He says, 'My competitors often think: Eh, I'm on a roll; I'm going to buy more planes, expand my fleet.' He said, 'I've been in this business a long time. The bad times will come.' And that's the farmer's attitude. In certain industries, it's very useful. Ben Cohen: Yeah. I think probably we should all think a bit more like farmers than basketball players, even if it's a whole lot more fun to think like a basketball player or a gambler. Right? |

| 53:47 | Russ Roberts: Let's turn to the technical side of this conversation, which I ducked earlier. I'm going to give you my take on the mistake that people made in the literature and get your reaction. It's a little different, I think, than the way you write about it. I think the way the data were originally analyzed in the 1985 paper by Gilovich, Vallone, and Tversky is that: if you took four shots and you went make-miss-make-miss, another night, you took four shots and hit all four, your shooting percentage in the first night was 50%--make, miss, make, miss. The second night it was 100%. And, then of course, there were nights where it was a different pattern, and so on. I think the mistake they made in thinking about the data--just to get the technical point across, because it's for people that want to dig into this--it's that basically they found that people only would shoot after a make they'd only reach their usual percentage. And what Josh Miller, and--help me-- Ben Cohen: Adam Sanjurjo-- Russ Roberts: Sanjurjo--what they found in reversing this claim is that, actually, the way the data is constructed, you should shoot less. It should show up at, say, 42% or so, or 40%. So, actually shooting 50% isn't your expected average. It's higher than you should by quite a bit, actually. And I think when people read that they go, 'Well, that doesn't make any sense because you should be shooting 50%. What do you mean you should shoot 40 after?' And it causes people, I think, to think about the regression to the mean or mean reversion in the wrong way. Because, I think what--the reason it's wrong is that if you should hit--make, make, make--four in a row, you've actually got three data points there, not one. So, in the original paper, they treated it as one data point--meaning, 'I shot 100% that night.' And actually it's three data points. It's a head followed by head followed by a head followed by--a 'make'--I use, as you and others do and they use heads and tails in the way to think about makes--to show it's not random. So, make, make, make, make, should be weighted more heavily than just 100%. I mean, if you make 40 in a row, is that still 100% that night? I mean, that's a wildly different thing than four in a row. But the way it's often represented--it seemed the way it was represented the original papers, it was one data point. A streak. Am I right, is that wrong? Is that the one way to think about the intuition of what they got wrong? Ben Cohen: Yeah. It's a very, it's a neat way of thinking about the bias. I mean, I think there are really two things here. The first is that, for anyone who is interested in this part of it, I would really encourage you to read the original Miller/Sanjurjo paper, which does this really elegant job of explaining a very complicated statistical bias. One that is so subtle that, you know, the world's brightest mathematicians and statisticians missed it for 35 years. It was not simply that the original paper missed this. It was that everybody missed it. Everybody looked at the same problem and they saw it in a new light, which I found really interesting. The second thing, though, is that, that '85 paper, is, through no fault of their own, was based on data that was cutting edge at the time, but now looks primitive. I mean, what we're able to do on a basketball court now, is data that wasn't available to those guys in their nerdiest, wildest, wonkiest dreams. I mean, there was only one guy at the time, who worked for the Philadelphia 76ers; his name is Harvey Pollack, and his nickname was Super Stat. He was this statistical savant because--in part because he bothered to keep track of the chronology of shots. So, the order in which they are taken. Play by play, essentially. Nobody was doing that time. Now we know everything there is to know about any given shot in a basketball game. We know exactly where it was taken. We know how far away the defender was from the person who was taking the shot. We can even quantify the probability of that shot going in for that single player taking the shot. Right? We know so much more in such granular detail that we are able to search for the hot hand--in part because it had been masked for 35 years. Because, when you do get hot, you take harder shots and they are less likely to go in. Right? So, when Steph Curry shoots from 35 feet with two hands in his face, it's not the same as when he is taking a layup. And yet that original paper essentially treats them the same. So, the world has changed over 35 years. And, I think that what that first paper found was incredibly admirable. And some of it, most of it still holds to this day. You know, we do see patterns where they don't exist. And we do overestimate trickiness, and we exaggerate the effect of the hot hand. But, whether or not there is a hot hand, I think we're not crazy for thinking that there is. And the world sort of changed our minds about that. The world changing and the way that we see the world changing--you know, it was sort of this whips-on[?] narrative. And that was one of the things that really appealed to me about this-- Russ Roberts: That's a beautiful story. Ben Cohen: This thing that we all think to be true, only to be told by really smart people that it's not; only to realize that maybe it actually was. And, wherever we land, you might land somewhere in that continuum. But, I think it's just really fun to think about. |

| 59:11 | Russ Roberts: The other part I liked thinking about, and I think your book is a great illustration of this, is the challenge of thinking about probability. It doesn't come naturally to us. A lot of what Behavioral Economics has done is to try to point out irrationalities. And I think we're in the middle now of a huge pushback against that. Some of that's coming from people like Talab and Gerd Gigerenzer, who are showing that actually, when you think about the context of that decision, it is rational, even though it didn't look rational to you. The academic probabilities are not intuitive to us most of the time, and a lot of the cleverer paradox is--like you write about, and I'm sure many listeners now--we won't go into it--but the Monty Hall problem challenges people. There are a lot of examples like this, where clever things are constructed by academics to show that people have biases or irrationality. And it turns out the context and the way you phrase the question is extremely important. Because we're often--let me give you a totally crazy example, the Trolley Problem. The Trolley Problem: 'Should I pull this lever and kill these three people over here, or let the trolley keep going straight and one person will die?' A lot of people don't like to, excuse me, 'and five people die.' A lot of people don't like to pull the lever. They don't like to push the person over the railing to stop the trolley because they have to be active, and they'd rather let just--it comes back to our question of control to some extent. I think I've given this example before. When I told this to one of my sons when he was younger, he said, 'Well, I don't want to push that guy over the railing. What if he pushes me back and I go over?' And, you know, that's a goofy--the academic says, 'No, but just assume that he can't do that.' But, your brain was not designed for that. Your brain was designed for the savanna when there were things that could kill you. The fact that you rationally worry about a guy pushing you back is not stupid, it's smart. And so, I think a lot of these paradoxes and tricky, clever probability problems, they're fun. I love them. I'm a sucker for them. But, I think lot of them are just, they're so devoid of context that the conclusions people draw out for them don't hold. Ben Cohen: So, there are two things I would say to this. The first is that there is this great irony to the way that we think about the hot hand because the great thing about that 1985 paper is that it forced us to rethink our beliefs. Right? It really tried to change our minds. Our priors were so strong in believing in the hot hand that what they found was just incredibly counterintuitive. And, then over the course of 35 years, that counterintuitive pearl[?] became conventional wisdom. And so, when people tried to flip it on its head and show that our priors might have been right, that was just as counterintuitive. Right? And so, that was appealing to me, and I think is sort of a microcosm of some of the stuff that is happening right now in economics, and people trying to understand the mind better and how we make decisions. But, you know, the second thing is that when we talk about randomness, especially paralyzing the human mind, in the book I write about Spotify and-- Russ Roberts: Oh yeah, I'm glad you're talking about this. I love that, talk about that. Ben Cohen: So, Spotify, a few years ago, was this incredibly successful startup company, but it had one big problem, which is the same problem that Apple had a few years earlier, which is that people kept making playlists, and random playlists, and-- Russ Roberts: Shuffle, they wanted to shuffle. Ben Cohen: they wanted to shuffle their playlists. And they kept complaining to Spotify that something was wrong with their shuffle button. It wasn't shuffling their music. Their music wasn't random. What Spotify had to think about, which is what Apple and Steve Jobs had to think about a couple of years earlier, was that pure randomness is hard for us to wrap our minds around. It's not the way that we want to listen to music. Pure randomness means that sometimes you hear the same song twice in a row, or you hear the same artist twice in a row, and that's not Spotify or Apple trying to curry favor with those record labels or doing something nefarious, which is what users were accusing these companies out of. It's just the way that randomness works. And so, both of these companies had to actually tweak their algorithms and change the code to give us music the way that we want to listen to music. Essentially what they did was, they take a playlist and they evenly disperse artists over the course of that playlist, so that you won't hear the same artist twice in a row, you won't hear the same song twice in a row. So, what they essentially did was they made playlists less random to feel more random. When you are looking for ways of showing that randomness is really hard for us to understand, it's hard to find a better example than that. Something that we all can experience. We have all set playlists on shuffle and swore that something in the algorithm is wrong or that Billy Joel paid Spotify under the table so that his songs would play more. No. That's just how randomness works. The fact that both of these billion dollar companies had to change their own algorithms to account for its users and give us what we want, it was just so interesting to me. Russ Roberts: Yeah, and of course, there's another human trait, which is--probably is survival oriented--which is to be worried about conspiracies. Right? And the idea that, 'Oh, this must be a trick on me, I'm misreading this pattern,' is a very normal and judicious thing to worry about in life many times. But, in these case-- Ben Cohen: Well, I think Amos Tversky said, 'We see patterns where they don't exist and we invent causes to explain them.' Right? In basketball, what he would have said is that we see hot hands and we invent a cause saying that the hot hand is real and that explains it. And, in Spotify and in Apple, it's something a bit more conspiratorial than that. But, that doesn't make it any more true just because we believe [?]. So, it does sort of make me listen to Spotify in a different way now, knowing that they openly admitted to changing their algorithms in response to this. Russ Roberts: Yeah. It's a great story, I love it. Again, it forces you to think about how we perceive patterns in the world and just- |

| 1:05:27 | Russ Roberts: Let's close with--since you wrote the book and I think I've given readers the correct impression that it's kind of wide-ranging--Van Gogh, Wallenberg, David Booth, Steph Curry, Spotify--I've left off a few. It's just packed with interesting-- Ben Cohen: The Princess Bride-- Russ Roberts: Princess Bride, Oh I forgot about Princess Bride, which is one of my favorite movies also. But, since you wrote the book, it says the book was finished, which was before March 10th, of course. It came out in early March, but you wrote it well before. Did you start to see things in real life or in your own life where you went, 'Oh, I wish I could have put that in the book?' and you couldn't? Ben Cohen: That's a good question. Yes, but my brain has been so broken by the last few months that it's hard to think of [?]. I will tell you, there was one story that I almost put in the book; and in fact, I traveled to Las Vegas to report it out. I was trying to think of what happens when we get hot. There are scientists who believe that when we say that we are unconscious, when we were in the zone, there are parts of our brain that are turning on and off, right? And they're inhibited. I thought, 'Well, what are other activities where your brain gets inhibited?' So, I went to Las Vegas and I went to the World Series of Beer Pong to try to figure out if those people report feeling hotter while getting drunker, while their brain chemistry is literally changing. And it was really interesting, and I almost told the story of the third World Series of Beer Pong, where everybody is still talking about this epic comeback that won these two guys a $10,000 check. But, I just thought it was a little bit too much. But, I do think there is something there. And, once the science gets caught up to it, it would be really fascinating to explore again. But, again, I think that, one of the things that I've thought about, for the last three months anyway, is what art is going to come from this very strange time in our lives. I mean, that is sort of the Shakespeare example. The world is changing and people are going to take advantage. There are people whose hot streaks are going to be rooted in this great upheaval and this incredible disruption to our lives. It's sort of macabre and it's a little bit uncouth to think about it that way, but we will see something change. It will be interesting 400 years from now to look back at this time in our lives. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Somewhere there's a Shakespeare--maybe it's you, Ben--writing three great works in a very short period of time. We all should get busy. My guest today has been Ben Cohen. His book is The Hot Hand. Ben, thanks for being part of EconTalk. Ben Cohen: Thank you, Russ. |

Journalist and author Ben Cohen talks about his book, The Hot Hand, with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. At times in sports and elsewhere in life, a person seems to be "on fire," playing at an unusually high level. Is this real or an illusion? Cohen takes the listener through the scientific literature on this question and spreads a very wide net to look at the phenomenon of being in the zone outside of sports. Topics include Shakespeare, investing, Stephen Curry, and asylum judges.

Journalist and author Ben Cohen talks about his book, The Hot Hand, with EconTalk host Russ Roberts. At times in sports and elsewhere in life, a person seems to be "on fire," playing at an unusually high level. Is this real or an illusion? Cohen takes the listener through the scientific literature on this question and spreads a very wide net to look at the phenomenon of being in the zone outside of sports. Topics include Shakespeare, investing, Stephen Curry, and asylum judges.

READER COMMENTS

Alan Goldhammer

Aug 10 2020 at 10:55am

Russ – great conversation. The fund manager you referred to who had a great winning streak against the S&P 500 was Bill Miller who managed the Legg Mason Value Trust fund. He beat the index handily for 15 straight years between 1991 and 2006.

Michael W Joukowsky

Aug 16 2020 at 6:09pm

Bill Miller’s lead analyst was Lisa O’Dell Rapuano. She was the one who discovered Amazon for Bill. She made him famous.

Morris DeShong

Aug 10 2020 at 3:21pm

I found it interesting when you talked about the need for spotify to alter it’s “random” algorithm to make it feel right. As a home remodeler for over 40 years I’ve always know it’s our job to make the job look right not necessarily be right. It can be a tough call when “wrong” is actually right. I wonder how many area’s of life this concept applies to. I can see a lot of research and and a book in there somewhere.

Dylan O'Connell

Aug 11 2020 at 8:32am

Quite enjoyed this conversation! Hearing the anecdote about Spotify and algorithms which are “too random for users to think they’re random”, reminds me of one of the most direct examples of this comes from gaming.

For instance, in Dota, and many peers, there can be a mechanic where on X% of attacks you get a “critical” attack, which does extra damage. The way the effect is worded, you would assume that each attack had an independent chance. However, it actually follows a rather weird distribution whose expectation is X%, but whose streaks “feel” more random to us (I.e. has Gambler’s Fallacy baked in… if you go on a long streak without a critical strike, you *are* more likely to get one on the next attack). You can see the example in Dota 2 here, but it’s actually quite widespread in gaming!

I’m not sure I quite buy Russ’ description (about sample sizes and etc) of the rebuttal to the Tversky paper, but I also admit I’m not sure I really get what he’s saying, so maybe that’s the issue. (From what I can tell reading the paper, the dominant change was that they were able to account for many changes to shot selection during a streak, both from the perspective of the hot hand player and from the opposing team, as well as many other factors, and just generally they had a far richer dataset, and controlled for many many things. But maybe Russ has a further point I can’t follow).

It goes without saying that evaluating “a hot streak” for a writer is very subjective (duh), but I do think that’s an important point when it’s being mixed in with a very quantitative study. Like, the point about Shakespeare’s hot year in 1605 is quite interesting. But while your individual opinion of the plays will vary, I’m not sure people would generally agree that this year “leaps out” among all the others. We think (so much of the details of Shakespeare’s life are unclear, it’s dangerous to read too much into any one hypothesis), that he wrote “Hamlet”, “As You Like it”, and “Julius Caesar”, and “Henry V” in about a 1 year stretch, which to me is a much more impressive run. And if you expand it another year in either direction, you add “Twelth Night”, “Much Ado About Nothing”, etc… basically, I’m not terribly convinced by the example, someone who has a really high batting average is bound to go on impressive streaks, basically by definition.

Overall, very enjoyable episode, thanks for hosting Russ.

Guy Kruger

Aug 12 2020 at 7:14am

I don’t get the thing with Spotify. From what I understand from the podcast (saying they “evenly disperse artists over the course of that playlist”) – that’s still random!

It’s just not a randomly chosen track but rather a randomly ordered playlist.

If I’m not mistaken, in combinatorics this would be regarded simply as a switch from random permutations with replacement to random permutations without replacement. Still just as random…

Guy Kruger

Aug 12 2020 at 7:25am

Oh wait. I think I’m wrong about that. “evenly dispersed artists” makes it not random.

Seth

Aug 12 2020 at 8:08pm

Any information on how often saying, ‘let’s get one back’ after the other team scores works? I’m amazed at how often it works when I play, but admittedly could just be confirmation bias.

PeterB

Aug 18 2020 at 11:44am

Can we equate the hot hand to the concept of variability control in repetitive processes? This concept is highly advanced in manufacturing systems where standard deviations and control limits are constantly measured, improved, and refined. Applying to basketball 3 pointers, the measured value would be the distance the vertical center of the basketball is away from the center of the circular rim. The difference between me and Seth C. would be vastly different. The tightness (control limit, std dev) of his shots would be much less than mine. In manufacturing processes, the variability is constantly being “tightened”…looking for ways to reduce the off-center distance. My thought is that when players make a good shot they have reduced their variability by remembering the feel or mechanics it took. They put themselves in a less variable “zone”. However, unlike machines the brain loses this over time. Machines also get “out of control” and need to be maintained to achieve low variability. Thus there is still chance involved based on standard deviation, but less so when the player reduces it by short memory of throw mechanics and concentration making streaks more likely.

Jeff McAlpin

Aug 19 2020 at 3:07pm

Listening to the podcast yesterday, I thought the opposite of a hot hand might be—cold feet!

Comments are closed.