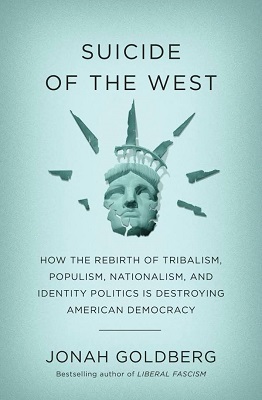

| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: March 8, 2018.] Russ Roberts: My guest today is Jonah Goldberg.... His latest book is Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Populism, Nationalism, and Identity Politics is Destroying American Democracy. Jonah, welcome to EconTalk. Jonah Goldberg: I am delighted to be here. And listeners should know: Russ has only looked at the galley of this book and does not know that I actually credit EconTalk in the "Acknowledgements," because I am such a crazy fanboy of this podcast. So, I'm delighted to be here. Russ Roberts: Well, that's very kind of you. Much appreciated. It's a fascinating book. It's a disturbing book. It's a somewhat depressing book, at times; and maybe we'll look for some bright spots on the horizon and in our conversation. But I want to start with a paragraph from near the beginning of the book. You say the following My argument begins with some assertions. Capitalism is unnatural. Democracy is unnatural. Human rights are unnatural. The world we live in today is unnatural, and we stumbled into it more or less by accident. The natural state of mankind is grinding poverty punctuated by horrific violence, terminating with an early death. It was like this for a very, very long time. Elaborate on that. And talk about what you mean by the Miracle, which is the unnaturalness that we're in the middle of. Jonah Goldberg: Right. So, what I mean--I'll just start with what I mean by 'unnatural.' If you took a jar of ants and you dumped them on a planet very much like ours, with our atmosphere, ants would do what ants do. And they would build little colonies and they would dig their little ant tunnels. If you took a pack of dogs and you put them in the wild, they would very quickly become a natural pack like they would. If you took human beings, absent all of the stuff that they learned from culture and education today and put them in the wild, they would not all of a sudden start building houses and schools and have startups. They would take to the trees, and have spears, and it would take a long time to discover spears. And they would behave the way that we are wired to behave. One of the core beliefs I have about a definition of--at the heart of conservatism--is this idea that human nature has no history. And so, when I say that 'capitalism is unnatural': if it were natural, if it were the way human beings, like ants or dogs or any other creature naturally behaves in its natural environment, we would have developed capitalism a little earlier in the evolutionary history of man. We would have developed democracy a little earlier in the evolutionary history of man. In the 250,000 years, give or take, since we split off from the Neanderthals, the amount of time where we had any conception of natural rights--particularly for strangers, right? People within the tribe, that's different. But for strangers, the idea that someone we just met has any dignity or any claim on justice--that is an astoundingly new idea in human history. And, this whole world that we live in--so, a big inspiration for this book is this idea you talk a lot about on EconTalk, which is: Hayek's distinction between the microcosm or the microcosmos, and the macrocosm. And, I take Hayek--I think Hayek is absolutely correct, where he says that we evolved to live in small bands of people--troops, tribes, whatever label you want to call them. And that's how our brains are structured. And our brains haven't changed very much in the last 10-, 11,000 years since the agricultural revolution. And so, this entire extended order of liberty and contracts and the monopoly on violence of the state--all of these things are really new. They don't come to us naturally. We have to be taught them. We have to be civilized--as a verb--into believing in these things. And this Economic Miracle--and so the Miracle is--and I was heavily influenced by Deirdre McCloskey; and I think she gets a lot right. We can talk about one of the things she might get wrong, later. But, you know, for, what is it, 7500 generations? For 200-, 300,000 years, the average human being everywhere in the world lived on average on about $3 a day. I think it's Todd Buchholz who says that man lived no better for most of man's existence he lived no better on two legs than he had on four. And, it is only when you get this radical change in ideas that comes from the bottom up--what I call the Lockean Revolution, but I don't think Locke gets credit for it. He just simply sort of represents it. For the first in all of human history basically in one place, this little corner of Europe, human prosperity, human wealth starts to explode. And that explosion radiates out around the world and is still doing so today. And that is a miracle. And the reason I call it a Miracle is not because I think God delivered it--the first sentence of the book is, "There is no God in this book." Russ Roberts: A promise you don't quite keep; but, I know what you meant. Jonah Goldberg: We can talk about it. Russ Roberts: That's all right. Jonah Goldberg: But, what I'm saying is, it's not providential. Right? God didn't suddenly decide to give us all of this bounty. It's a miracle because you people, you, you know, you witches and warlocks of the economics profession have not reached a consensus about why the hell it happened. You know, there is a consensus about the $3 a day stuff. But there is not a consensus about why this miracle or this explosion of rights, liberties, and prosperity happened. And, no one planned it. We stumbled into it by accident. And, my argument is that we should be incredibly grateful for it. And, therefore, protective of it. You only protect those things you are grateful for. And, that's what I--that's sort of the opening precis of the book, I guess. |

| 7:12 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. Just a couple of comments. I always think of it as the goose that lays the golden egg. If you have a goose that--all of sudden you get this goose that happens to be laying golden eggs instead of regular ones--you'd kind of want to be interested in what keeps the goose healthy and alive, and how this came to happen, as you keep it going. And we seem to be somewhat oblivious of it. I think it's a human trait to be--take things for granted, and to think that tomorrow will be like yesterday. And so, the era of progress we presume is just a natural thing. And, as you point out--it's hard to accept, but it's not so natural. Jonah Goldberg: Right. Russ Roberts: And just to expand on the Hayek point, in The Fatal Conceit, he says: This micro-cosmos and macro-cosmos, we have two --we have to have two ways of thinking about the world. In our small families or our bands or our tribes or our communities, we have a more socialist--what you and I would call a Socialist--enterprise. We don't sell stuff to our kids: typically, we share. It's top down, not bottom up. In the family, the parents tend to run things. And, that's very appropriate in a small group that's held together by bonds of love, for genetics--whatever keeps it together. And, he says, we have to have a different mindset when we go out to the extended order--when we are traders and commercial actors. And he said, we have a tendency to try to take the beautiful and poetic ethos of the family and extend it into the larger order. And he says that leads to tyranny. Jonah Goldberg: Right. Russ Roberts: In a way, that's--that's what I want to--you might--it's one of the things you are worried about in your book. Which is that the tribalism that we are hardwired for seems to be spreading beyond the immediate family. Jonah Goldberg: That's right. I think it's worth pointing out: It is disastrous going both ways. Russ Roberts: Hayek makes that point, yeah. Jonah Goldberg: Right. Right. It's disastrous to treat the larger society like a family or tribe. But it's also disastrous--getting your g'mindschaft[?] and your Gesellschaft is always a problem. And treating your family like a contractual society destroys the family. And, both are really, really bad. And I agree that it's not just that we are Socialist. I mean, the way I always put it is: We are literally Communist, in the sense that in my family it is: From each according to his ability, to each according to his need. You have a sick kid, you don't do any kind of calculus about what their contribution to the family is. You just do whatever they need. And, yeah. So, part of my argument is that--you know, the Roman philosopher Horus has this line where he says, 'You can chase nature without--you can chase nature out with a pitchfork, but it always comes running back in.' And, so, part of my argument is that human nature is always with us. Right? We are born with it. That is the preloaded software of the human condition, and you can't erase that hard-drive. All you can do is channel and harness human nature towards productive ends as best you can. And when you don't do that, human nature will assert itself. And I think of this in terms of corruption: That, just as if you don't maintain their upkeep--a car, a boat, or a house--the Second Law of Thermodynamics or entropy or just rust will--you know, rust never sleeps. Eventually, nature reclaims everything. And that's true of civilizations, too. And if we don't civilize people to understand this distinction between the micro- and the macro-cosm, what inevitably happens is that the logic of the microcosm, the desire to live tribally which we're all born with, starts to infect politics. And if you are not on guard for it, it can swamp politics. And this is why I would argue that virtually every form of authoritarianism, totalitarianism--whether you want to call it right-wing or left-wing--doesn't really matter to me any more. They are all reactionary. Because they are all trying to restore that tribal sense of social solidarity--whether, you know, it's a monarchy or treating the leader of the country as the father of the country or the Fuehrer or whatever you want to call it. Or whether you are just saying that the entire society is just one family. Whether it's nationalism, or socialism, or populism--all of these things are basically the reassertion of human nature, which says: I don't like your artificial constraints on my human desires and my desire for my group to be victorious. And that is the fundamental form of human corruption. Russ Roberts: I think that's profound. And I used to be much more of an optimist. I think on my Wikipedia page, which I've never tampered with--but I think it talks about on the early days of EconTalk I used to always ask people if they were optimistic; and I always tried to end on an optimistic note. I am much less optimistic in 2018 than I was in 2006 when EconTalk started. And one of the things I've been obviously aware of--I think any thoughtful person has to be aware of--that, things have changed a lot in the last 5 years, not just in America but around the world. Populism is definitely on the rise. Tribalism is definitely on the rise. Or at least, it appears to be. There is a question of whether social media has just made us more aware of it. I wonder about that. And we've talked about that on the program as well. But, the world seems to be--I think a thoughtful person has to be aware--that the veneer of civilization is thinner than you might think. And I think that's what--another way to say, the Horus quote about human nature rushing back in, or whatever is dark in the human heart rushing back in. |

| 13:21 | Russ Roberts: But I want to challenge the claim about nature reclaiming--whether civilization is something like a car out in a field. It's a beautiful metaphor. And it's haunting and it grabs your attention. And it effectively--it's very effective. It did alarm me. And it has a disturbing[?], creepy feel to it. It's like a scene from a horror movie. And it's definitely true, that stuff left out in the woods tends to rot. But, is that really true about civilization? That is--and one of the great things about economics--excuse me--about capitalism, about economic freedom--is that you don't have to understand it. And I think I've used the same metaphor of the ant colony--the ant trundling down the path back to the ant hill bringing some pheromone with it from some food source--is unknowingly helping to guide the colony. And the cumulative effect of all the different ants is going to have that impact. The ants get in a war. The queen--the queen bee in a beehive; and I think it's a queen ant: whatever it is--but, 'The Queen' makes it sounds like she's in charge. She's not. She's just the sort of repository of the wisdom of crowds that the ants or the bees bring in. And that steers, unintendedly, by the warriors and the workers. It changes the ratio of new kind of ants that get created. It's an extraordinary thing. And, we have the same thing. You know, you are trying to do the best you can for your business, or your kids, in your commercial dealings; and you help create this wonderful division of labor that Smith understood creates prosperity. So, why do I have to understand? What do I have to worry about? I'm doing fine. I'm doing my little thing. It's pleasant that, as listeners to EconTalk you learn more about how the colony works, that the ecosystem of economics works: that there are these incredible connections that spur cooperation with anyone's knowledge--no one's planned. The so-called "invisible hand"--that's lovely. Why is it at risk if I don't understand it? Why do I have to know, think about it? How is it going to get reclaimed by nature and start to rot? Jonah Goldberg: Okay. It's a fair question. Russ Roberts: I can keep asking it. You want me to keep going? No, go ahead. Slightly longer than I intended. Jonah Goldberg: No, no, no. It's fine. So, I guess, here's a good point for me to make my argument against Deirdre McCloskey, who again was a huge influence on me, and all this. She argues-- Russ Roberts: And you cite her many, many times in the book. Jonah Goldberg: Yes. She argues that the--what I call--call it the miracle, call it the Lockean Revolution, call it whatever you want to call it--this explosion of prosperity and natural rights--and rights--and the sovereignty of the individual and innovation all comes about because of words. And, what she means by words is our--is ideas. For most of human history, innovation was considered a sin. You know, literally in the Catholic Church it was the sin of caritas[?], which means questioning a natural order, where you had guilds and priests and aristocrats who were constraining the market for their own benefit, channeling resources to themselves, limiting competition. And, by accident--again, by accident, partly because of the Protestant Reformation but partly for other things, you have the emergence of a middle class, the sort of bourgeois ideology comes about where people start asserting their rights. And all of a sudden innovation is seen as a good thing, particularly just in England and Holland; but then it starts to spread. So, it's ideas. It's words. It's not something structural; it's not the accumulation of capital; it's not slavery; it's not empire. It's ideas that change. And I think that's largely[?] it. I think she's too hostile to the sort of Douglass North institutional stuff, which I think is really important, too. But, words create the world that we live in. That's how we understand ideas. I should say language, because there's more to language than just words. Russ Roberts: Yeah. And I would just--I would add--I think she would add, rhetoric. Jonah Goldberg: Right-- Russ Roberts: That, the way we frame, the way we see ourselves, the language we use to describe the narrative of our lives and our culture and our society. Jonah Goldberg: That's right. I mean, one of the ways I put it is that: A civilization is simply the story that a society tells itself about itself. And, the Achilles heel of that argument is that can be created by words can be destroyed by words. And I think McCloskey is too optimistic about the ability of this thing we call Western Civilization or liberal democratic capitalism to be on auto-pilot. And here, I'm much more convinced by Joseph Schumpeter. And I have quite a bit about Schumpeter in the book, although not nearly as much as I originally wrote it--I cut a lot out--where, Schumpeter predicts the demise of capitalism. By saying that the ranks of the very rich--the industrialists, the business class, they have kids who don't want to be entrepreneurs. They want to be idea-merchants, essentially--whether it's artists, poets, Hollywood producers, writers, journalists, lawyers. These are idea merchants. And, I believe that one of the problems we have in our society, and it particularly is true in the humanities on college campuses, is that we have generated a vast class of people who are professionally invested in the idea of undermining commitments to the market--even to democracy. Certainly to free speech. They are becoming increasingly hostile to the story we tell ourselves about ourselves. If you look at the Howard Zinn version of American history, the only legitimate history to tell is the history of all the bad things that we have done: and that capitalism has done. And I'm in favor of telling all those things, if they are true. But we should also talk about the positive things. And we don't. And, as a culture we have generated this vast industry of people belittling the society that we live in, saying that we shouldn't be grateful for this society; that we should feel entitled--entitlement being the opposite of gratitude; and that we should be resentful. And, the argument--so, the reason why people like you, who, all praise and honor are on the right side of these arguments--is that the world is a better place because you do this podcast and you try to make these arguments. The whole point of a civilization is that you've got to fight for it. And I don't mean necessarily with guns and knives and bombs, although--sometimes in history that's necessary--but with words. By actually defending the good things about the market. Defending, using rhetoric for positive aims. Right now, something like one in two Millennials would rather live in a Socialist or Communist country--or at least they say so. And that should be dismaying. Because they are wrong. But, so much of our problems today isn't that all of America is bad, or all the West is bad. It's that most of the people who really think it's good are too busy with their own lives to do much by way of standing up and defending what we've got. And that's a problem. And that's the 'Suicide' in The Suicide of the West--is that, this is a choice that society makes: to defend itself or to let it sort of seep back into its own nature. Russ Roberts: Yeah--I sort of agree with that. I don't think society makes choices. But I think all of us, individuals, if we are not careful may keep our head down too much, the people who keep their heads up are going to take charge and do some damage. |

| 21:09 | Russ Roberts: I just want to put a little footnote to your point about emphasizing the bad versus the more general picture. One of the things I really like in the book is your point that our society, our history, America's history often gets criticized for hypocrisy. 'All men are created equal'--what about women? what about slaves? Etc., etc. And you make the point often in the book that, by laying down that marker of equality, we gave people like Martin Luther King and others the cudgel to beat America into a better world--into a better country, into a better society. And I think that's an extremely important point in the culture wars about colonialism and various 'isms' of sexism, racism, etc., I think that's often forgotten or not noticed. And I thought that was brilliant. Jonah Goldberg: Thank you very much. People want to point out how we had slavery. Well, of course we had slavery. Almost every inhabited continent since the agricultural revolution had slavery. What was new about the West and what was new about the--and America doesn't get that much credit for ending slavery, because we never should have had it in the first place-- Russ Roberts: And [?] people died to stop it--which is awful. Jonah Goldberg: Right. But it's also saying something: this idea that we've never come to grips with slavery--well, we did have this ugly war where fellow citizens killed each other. And then we amended the Constitution a few times to get rid of it. But the point was, was that, starting with Abraham Lincoln reinventing the Declaration of Independence and then Martin Luther King taking it. And then, you know, I've been very rough on Barack Obama; but, you know, Barack Obama made that argument repeatedly--that, the best--this is the point about--the best story we tell ourselves about ourselves. What are the best ideals about ourselves? And those can be found in the Founding. And those can be found in the arguments of John Locke, which you just have to extend out to their logical conclusion. That was the gift that comes from back then--is, the seed stock for this rhetoric that transformed the world. |

| 23:26 | Russ Roberts: So, I think the--I'm a big fan of Deirdre's. I think rhetoric matters. I'm not sure if she's right--who knows? It's tough; it obviously can't be proven; and it's a provocative thesis that rhetoric matters as much as she says it does. But I do think the stories that we tell ourselves have changed over the last 200 years. Obviously. And whether that's a response to the underlying change or whether it's the causal agent is kind of irrelevant. Obviously, I think causation runs in both directions. And I earlier, a few minutes ago, challenged you on this capitalism thing about: Doesn't it have some self-sustaining characteristics? And I think it does. I do think--but I do think that in democracy, your point is easier to make. So, I want to try to make it in a different way than you make it in the book and see if you agree with me. In my view, the Constitution is irrelevant as a restraint on government power except in two areas. Two Amendments--First and Second. We still have some devotion to freedom of speech: it's affected our campaign finance; it does still affect government's power to limit certain speech that "it" doesn't like, or that powerful people don't like. And we still have the right to bear arms. Both of those are under attack from the Left and from the Right. And, as you point out, I think maybe I saw somewhere else, you know, majority rule--not [?] neither of those amendments right now. It's not clear you'd get a majority in a referendum to suppose those. And the whole idea of the Constitution is, in my view, now seeing it through the lens of your book in a very helpful way, is: it's to restrain--on the narrower sense it restrains the power of government. On the deeper sense it restrains the rule of humans over the, instead of the rule of law: it restrains the corruption and return to tribalism and authoritarianism that you of course and I, we're both very worried about. And what I see the last hundred years is the slow erosion--it's very slow. It's very slow; it's like rust: you don't see it. But, every day you go up to the car that's sitting in the field and it looks like it looks like yesterday. After 10 years, it doesn't look as good; and after 100 years it's radically different. And we've radically changed both the effectiveness of the Constitution and the way we talk about it. And, I think we've gone to a world, what I think of as a case-by-case basis: 'We don't want to use principles: let's just look at this case. Because principles, in any one case, might be wrong. So, let's not let them ruin it. Let's look at this case. Should it apply here?' And often the answer is no; so, 'Okay. Let's go to the next case.' And of course, that debate is [?] reasoned, civilized discussion of thoughtful truth-seekers--it's an angry, political, manipulative, self-deceiving, no-necessary-incentive to be fully informed screaming match. And so, we're losing--I think on the democracy argument, we're heading down a very dangerous path. Jonah Goldberg: No, I think that's right. And, for me, one of the things that I sort of learned in a more visceral way while working on this is: It's interesting, when you read the Constitution, there's only--or the Federalist Papers--there remarkably little opining about what would be good or bad policies or politics. It's almost all procedural. Because, for the Founders, what they were worried about wasn't that the government might do x or y. It's that: Just power qua power would concentrate itself too much. I feel like I'm bringing coals to Newcastle bringing up Adam Smith with you, but-- Russ Roberts: Do so. Do so. Although, somebody did tweet, when you said Adam Smith, and[?] say 'Adam who?' But, I know the one you are talking about. It's a good line. Jonah Goldberg: So, when Adam Smith says--you can probably do it by heart; I can just paraphrase it: You'll never get two businessmen or people in the same trade sitting together where the conversation won't eventually turn to a conspiracy against the public good. And, the Left likes to mangle that, making it somehow about the nature of businessmen. Or industrialists. Or the ruling classes. Russ Roberts: Yeah: 'They're greedy. Unlike the rest of us.' Jonah Goldberg: That's right. And that's the problem--it that the reality is, is that-- Russ Roberts: We're all greedy-- Jonah Goldberg: We're all greedy. Self-interest is built into us. And whenever people have a group self-interest, a common interest, they will conspire against all greedy. Self-interest is rue of teachers' unions; that's true of football teams; that's true of everybody. Because it is what the evolutionary psychologist John Tooby calls the coalition instinct: we form around an interest, and then we defend it against all attacks, reasonable or otherwise. And, the Founders understood this passionately; and they called this coalition instinct 'faction.' And so, we're recording this amidst a lot of hullabaloo about protectionism and trade. And, it seems to me that the best way of understanding this is that the steel industry is a faction. And, there's nothing wrong with factions--figuring out how to maneuver for the best interest of their members, whether it's teachers' unions or anybody else. It only becomes bad when you enlist the power of government to your side and pick one winner against other factions. And that's what the Founders want to protect against. And that concern has just flown by the wayside in the political moment that we're in, where basically every faction claims that they have the right to use government force any way that they want. Before you were talking about principle: it reminds me--I think it's in the book--one of my favorite lines from Huey Long who was one of the original great populist politicians--he says, 'We've got to stop talking about principles and just do what's right.' And that's the attitude that pervades vast swaths of the Left, and the Right these days. |

| 29:55 | Russ Roberts: Well, what fascinates me--and you don't talk about this directly, but it's, again, part of what you are talking about--is that, you and I, neither of us are big fans of either the current President or the past, most recent President. Jonah Goldberg: Right. Russ Roberts: And, one of the things that alarmed me, and I'm sure it alarmed you about the last 5 Presidents is the growth in executive power: the ability of Presidents to act unilaterally and to do stuff that is "undemocratic." And when I would point this out, I think a lot of people's reaction is, 'Well, but he's good.' So, it's okay that he's powerful. And then you get a President that is also more powerful than the one before--that seems to be the trend--and the people who were cheering when their side had all the power and did all these extra-legal things, now they're horrified. You'd think the reaction would be, 'I think the President should be less powerful.' Instead, their reaction seems to be, 'Oh, we've got to get our guy back in.' And I don't understand why people don't see that. Now, I'm going to digress here, for a minute. You know, one of my favorite EconTalk episodes is with Bruce Bueno de Mesquita from, I think 2006 or 2007. We were talking about power, and he mentioned King Leopold of Belgium. And King Leopold of Belgium, he pointed out, was beloved in Belgium for a lot of reforms he made in social policies. He was not so popular in the Belgian Congo, where he was the instrument of murdering--murdering--I think, certainly hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people. And, in the Belgian Congo, he had a free hand. It was his colony, Belgium's colony. And at home, he was constrained by the Parliament. And Bruce's question was: Which one is the real King Leopold? The one who was sort of a moderate social reformer, or the murderer? He said, 'Well, you'd want to look at the free hand.' And your point really is, 'Well, we're all like King Leopold when we have a free hand.' We're all dangerous. We all come with that same hard-wired view. And this idea that somehow, 'Well, but we're so civilized now. We don't have to worry about America becoming a tyranny. Are you crazy? We're so much more educated.' And that's just a total misunderstanding to me of education, human nature. And even today, the Left, which is horrified at President Trump--I don't think--I think they just want to get a better guy in. And I just want to get less power in the Presidency. Jonah Goldberg: Look, I think that's exactly right. Two quick points on this. One is: I have problems with the way people use Lord Acton's quote about 'Power corrupts absolutely'; but in this sense-- Russ Roberts: Why? What's your problem with that? Jonah Goldberg: Well, I think it's true. And I was just about to explain why I think it's true. But, historically, my understanding, and I wrote about this in my last book, is that--and it's relevant to this discussion in a lot of ways--is that: Acton coined that--that lines comes from a series of letters, correspondence that he had, with a guy whose name is Creighton, who was a historian of the Papacy; and he was writing about history of Popes. And, the historian was asking, 'Should I make allowances for the bad Popes because they were powerful and they did good things, but they also did bad things?' and all that kind of stuff. And Acton's point in that context was not that absolute power corrupted the powerful. It corrupts the people around him. In that, you make allowances--you just--and again, we don't want to get into the politics stuff. But, you look at what have happened to a lot of my friends on the Right who have said, with blinding passion, x--whatever x is. Whether it's free trade or pro-immigration or whatever. And then you get Donald Trump into power. And Donald Trump comes in screaming y. Russ Roberts: Instead of x, you mean. Jonah Goldberg: Instead of x. And all of these people, who have invested their careers and their integrity in arguing for x their entire adult lives are, all of a sudden saying, 'Well, maybe it is y.' Or, 'You know, Donald Trump is brilliant and he knows things better than I do, so it is y.' That is--so, like, in the story of The Emperor Has No Clothes, the corruption is, all the people who are willing to say that he had great clothes on. Russ Roberts: Well, the fascinating thing for me is that--this--I understand why people say that who want power, right? We understand why absolute power corrupts absolutely. And I appreciate your extended thoughts on Acton. And I want to just add that: At least he said it. That's a huge-- Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. Russ Roberts: No, I mean, usually we misattribute insights from various people-- Jonah Goldberg: That's true-- Russ Roberts: but I think he did get--that he said it, I think is, we recognize that. It's certainly a plus for accuracy. |

| 34:55 | Russ Roberts: You know, people have always changed their views, and adjusted their views, and retold the story to themselves because they want to be on the right side of power. Not the right side of history. The right side of power. Why is it--and this is a puzzle that I think a reader of your book has to ask, and I'm not sure you answer it, and so--tell me if you did; and if you didn't, what your thoughts on it are. Why now? What is, about this moment, that's caused tribalism? And we haven't talked enough about what that is. But, the partisanship--it's not just partisanship; and we've talked about this in other--we recently talked about it with Pluckrose and Lindsay, in that episode. It's not just, 'Oh, I don't agree with you.' It's that: 'My team is always right; and your team isn't just wrong and always wrong: it's evil. It's a threat to our future.' And both sides, Left and Right, are making that argument today. And that seems to me to be the road to violence. We're really at risk. So, why now? What's different? Jonah Goldberg: So, I think I do try to answer this question. And I think you are right. I have, actually a New Yorker cartoon, it's my favorite New Yorker cartoon that my wife had blown up and framed for me for a birthday present. And it has two dogs sitting in a bar in pinstripe suits and drinking martinis, and one dog says to the other dog, 'You know, it's not good enough that dogs succeed. Cats must also fail.' And, that's the world that we're living in, now. Right? Where, I think I used the phrase in the book, 'Ecstatic Schadenfreude'--where all you want--that a position or statement or policy, so long as it makes the other side cry. I mean, all those nonsense on Twitter where, 'Your tears are delicious,' and 'butthurt'--it's all so juvenile. But that is what defines vast swaths of our politics today. And it's pathetic. So, I think part of why we're there--and I think this gets back to what I wanted to say about the thing about, you know, 'getting our guy in power versus your guy in power,'--part of it is, it's like, in England in the 1600s, if you had a Catholic on the throne and you were a Protestant, that was felt as a threat to your very existence and your self-understanding, and your understanding of your society. And vice versa. And, for a long time now, the Presidency has become more and more of a symbol in the culture wars. And, when our guy is on the throne, as it were, that's a symbol that our side is winning, and we're heading towards the kind of America that we think we should be in. And, when the other guy is in power or on the throne, it is the sense that everything is coming unraveled. And I think one of the reasons why we are in this moment now is because civil society is in such terrible shape. And this gets us back to where we were at the beginning, with the microcosm and the macrocosm. The only place where you can reliably have a sense of real meaning, a feeling of earned success, a feeling of true belonging, is in the microcosm. You can get a sort of a cheap, fake version of it in the macrocosm during a time of war, when the logic of the micro-cosm actually does apply to the macro-cosm. Right? I mean, that's what a moral equivalent of war argument is: we all have to drop what we're doing and become nationalists, right? And there are these moments of fever-pitched nationalism, or socialism, or populism that serve as a substitute. But, in terms of an actually satisfying life, you can only get that sense of feeling needed--because that's what actually a satisfying life is, is when you realize that others that you care for need you and value you. And you can only get that in the microcosm. And that's what civil society is. It's a thousand different little microcosms. And as those start to break down, particularly the family, but also local communities, the receding of religion in life, I think that one of the things you have is--you don't have--Robert Nisbet, one of my favorite sociologists, called it the quest for community. We are hard-wired with this. We want to live in tribes. We want to live in little platoons. And, if civil society does not afford that to us, we do not lose that hunger. We look elsewhere. And, more and more in our politics, more and more in our life, the only place that is promising that kind of meaning is politics. And the Democrats have been doing it far longer. It was FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt] who coined 'the forgotten man'. And, when LBJ [Lyndon Baines Johnson] was pressed to define what the 'great society' was, he said ultimately it was about love. And, you know, 'The Life of Julia, and all that stuff that Barack Obama told about how government is the one thing that we all do together, in the first sentence that was uttered in the Democratic Convention in 2012 was, 'Government is the one thing we all belong to.' Which creeps me out. And probably creeps you out. But, that's--but we're not the intended audience. Russ Roberts: A lot of people think it's a beautiful thing. And any time I complain about it on this program, I get angry emails and comments. But, I agree with you. I think it's not a good thing. Jonah Goldberg: And so, national parties are selling meaning. And, the Republican Party is a late arrival to this. And they have capitulated--or, I should say, sort of, Conservatism, Inc. has capitulated to a lot of this stuff. You look at the ads from the NRA [National Rifle Association], and so much of it has nothing to do with guns. I agree with the NRA on most of its gun policy stuff. But this sort of seething resentment and cultural divide politics that they are peddling creeps me out. And so, I think one of the things that is happening is that civil society and local community offer less opportunities--there are fewer opportunities to provide meaning. More and more people, as Robert Putnam would put it, retreat or hunker down. They retreat to social media, which exacerbates all of these problems. And they follow politics like it's entertainment. Russ Roberts: Oh, for sure. Jonah Goldberg: And, the best example of this--there's a blogger, Ace of Spades, who--I no longer, get along with too well--but he coined this phrase which I think was kind of quite brilliant, called the MacGuffinization of Politics. Which, you know, in film, the MacGuffin is just the thing the hero wants. Right? So, the Maltese Falcon is the classic McGuffin. Or the briefcase in Pulp Fiction is a classic MacGuffin. And, the media, both rightwing and leftwing and mainstream, they cover politics like public policy is the MacGuffin. And so you have Barack Obama saying, I think it was 28 times, that he could not unilaterally do DACA [Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals] because the Constitution prevents him from doing that. Russ Roberts: You're talking about the--DACA is the Dream--[?] status. Jonah Goldberg: The Dreamers [?]. It's a little different than Dreamer, but yeah--helping these kids who came here out of no fault of their own; and I think we should do something. My point is not about immigration policy. But, he said, over and over again, he could not do this because he's not a King; the Constitution prevents him. And then, he just decided to do it. He reversed himself. And almost no one in the media covered it in terms of 'Oh my gosh! The President is violating the Constitution--the Constitutional principle--which he had established just a week ago.' They all said: Aha! The hero of the story has overcome a problem. And, look what the bad guys are saying. And that's how Fox News covers Donald Trump, because he's the hero and whatever he wants is the MacGuffin? Even if he contradicts himself? And the sort of Left wing or mainstream media, the way they cover Donald Trump is: he's the villain. But, the point is, is that everyone is talking and thinking in terms of entertainment and drama and reality show. In that universe, that sort of romantic universe, arguments about the Constitution-- Russ Roberts: Don't ruin the plot! Come on! I need[?] a deus ex machina here. Don't-- Jonah Goldberg: But that's the problem: whenever you see a movie that you actually know something about, and you turn to the person next to you and you say, 'You know, it doesn't work that way,' they say, 'Shut up!' Russ Roberts: Yeah. 'Don't ruin the movie for me.' Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. |

| 43:06 | Russ Roberts: My favorite example of this, as an economist, is the Bush Administration and the policy makers surrounding it, at Treasury and at the Fed. When Bear Sterns wasn't going to be able to keep its promises, the government made sure that they were purchased over a weekend--and because it was unrealistic, more for political reasons, the purchaser wasn't able to do the due diligence, figure out exactly what they were buying. It's like everyone said, 'Don't worry. We'll take care of it.' That was extraordinarily uncapitalist, to take an example, just one example of what[?] was uncapitalist and what was instead crony capitalist during the Financial Crisis. And yet, when Lehman Brothers was about to go bankrupt, they said--they actually claimed, they actually think we're stupid and suckers. And, as you point out, movie-goers, they are going to love this story arc, because the story arc, there was: 'Oh, we couldn't do it again.' And I think--somebody--I think Bernanke says, 'Yeah, we just--it wasn't--the rules,' or why was it that creditors of institutions that had taken risks with money, that were horrific, should get back 99--should get back 100 cents on the dollar? 'Oh, we couldn't intervene in markets, and we'd made promises.' Or they couldn't punish the executives: 'Oh, that would be, it wouldn't be capitalist.' Why is it that some things are capitalist and some things aren't? Why are some things constrained by the rule of law and other things aren't? And then you start to think: Well, maybe it doesn't have anything to do with the rule of law. Maybe it's just, I'm helping my friends when it's convenient to help my friends. And, I like to point out--no one's ever written about this; people out there who have potential to write about it, I wish they would look into it, but I've never seen anyone write about it. Lehman Brothers' creditors, its largest creditors, were not American banks. They were foreign banks. Jonah Goldberg: Hmmm. I did not know that. Russ Roberts: Now, is that relevant, for why their creditors had to eat a lot of their losses? It seems--I don't know--it seems possible. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. Russ Roberts: But their hand-wringing: 'Oh, yeah, we couldn't--we had to.' Nnn--it's like, 'Really.' And by the way, I just want to--this is a total digression, but at least it's in the book--one of the coolest things in the book is a paragraph where you point out, about human nature, that when we talk about going to movies or these kind of narratives that we sit and are entertained by, we use this phrase, 'The willing suspension of disbelief'--that, when we sit in a movie, we pretend that it's real. We're going to cry when this character dies, even though it's a fictional character. But, you point out, it's not the willingness. It's the unwillingness. We have no--it's so natural to us to suspend disbelief and just immerse ourselves in a narrative[?]. And I think for political purposes and understanding, what's going on, I think that's a very powerful insight. It's not a digression. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. No, I like the digression. And it's--it's true that we just watch[?]--and again, I don't want to get into--we have people listening on all sides of the political aisle. But, I think of it, as a matter of analysis, objectively true that Donald Trump has broken the blood-brain barrier between entertainment and politics. Russ Roberts: Oh, for sure. Jonah Goldberg: And I said, in 2015, that I don't think Democrats appreciate the precedent this is setting. Because, you know, Republicans--our list of--and I use 'our' advisedly-- Russ Roberts: Speak for yourself, Jonah. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. Of, of, of celebrities--you know, after Ted Nugent and Scott Baio, it kind of runs dry. And meanwhile, look at all this talk about Oprah, running. Look at all this talk about Tom Hanks. The power of celebrity in this culture. It used to be that this was one of these great divides, culturally, where, like, Wall Street people thought--you know--and throughout almost all of human history, from Kabuki to ancient Greek theater: Actors were considered a very low-class part of society. And now, I think, because of human nature, we are turning them into--essentially, you know, celebrity is becoming a de facto kind of aristocracy. You know, we talk about Hollywood dynasties. And we also talk about political dynasties. That's all human nature reasserting itself in weird, funky ways. And-- Russ Roberts: Well, to be fair to Donald Trump--he's really just the natural progression. You can start it whenever you want. You want to start it at Reagan? He's a pretty good example of an actor who was able to turn those acting jobs into a successful political career. FDR [Franklin Delano Roosevelt] understood that he was handicapped--you never saw him in a wheelchair. The theater of politics is very old. Jonah Goldberg: You know, and I agree with that. There's always been some theater in politics. But, to defend Ronald Reagan for a second: the guy actually did his homework. And, he had been a Governor. And he read Hayek. He learned a lot when he was a spokesman for GE [General Electric]. And, he at least understood that he had to pay his dues about understanding what he was talking about. And so, I agree with you it's a process. And you know, mass entertainment, starting with FDR and radio, has affected[a second?]--and obviously TV [television] and JFK [John Fitzgerald Kennedy] and all that--has affected politics in a lot of ways. And so, I agree. Donald Trump didn't start this. He is--but he's also not going to finish it. This trend is going to continue. And, um, it is--it doesn't seem to me--like, a lot of people make fun of the movie Idiocracy. But, in a lot of ways that seems to be where we are heading. Where, life is a TV show now. And, the problem is, as you point out, our brains are not wired to say, 'Oh, this is fake,' when we immerse ourselves on things we watch on TV. And, um, we can all get MacGuffinized. We can all get swept up into the sort of entertainment value of all this stuff. Which naturally encourages tribal thinking. Which naturally appeals to, not our reason, but to our emotions. And, that's what populism has always been: Is this appeal to emotion over reason. And, that's what has always been dangerous, whether it comes with a Left-wing variety or a Right-wing variety. The only populist movement I ever had any sympathy for were for the Tea Parties, because at least they were arguing--they had the right rhetoric, as far as I was concerned, about back-to-basics, living within our means, living by the Constitution. But, for the most part, you know, William Jennings Bryan had the best summation of populism, where he said: 'The people of Nebraska are for free silver. Therefore I am for free silver. I will look up the arguments later.' Russ Roberts: Yeah. That--I'd say that insight goes from all of us. We have this very natural tribal instinct to figure out what the tribe wants, and then, or what's good for the tribe. And then, 'We'll justify it later.' We don't like to think of ourselves that way. We like to think of ourselves as truth-seekers who find the right arguments and then join the right tribe after that. And I think that's a misunderstanding of human nature. It's why, I think, the pragmatists' philosophical movement, the pragmatists, are correct: That, um, reason--it goes back to Hume, of course, that reason is overrated. That we tend to oversell our own ability to reason, and think up later what comes next. And Haight, Jonathan Haight, of course plumbs this very well in The Righteous Mind. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah, no; I agree. I got a lot of The Righteous Mind. One day, perhaps in the future, I can come back on and argue with you about pragmatism, because I have a lot of problems with Dewey and James and what the progressives did with pragmatism. But, in general, I agree with you in the sense that you mean it that: It's about--Democracy is supposed to be about arguments. It's supposed to be about disagreements. It's supposed to be about--you know, the whole idea of the Enlightenment, and, or at least the Scottish Enlightenment, which is the one I like--I'm with Mike Myers when it comes to enlightenment: If it's not Scottish, it's crap. But, um, it's supposed to be about arguments. It's supposed to be about the power of using reason and persuasion to come to your side. That's what politics is supposed to be about, going back to Aristotle, is this idea of persuasion. And one of the reasons I think we are in such a mess these days--and this is something I know happens on the Left, but I'm much closer to it on the Right, because I live in those, you know, that ecosystem--is that you can make a pretty good living talking to audiences that already agree with you. Russ Roberts: Yeah. And, speak to the choir. It's so much fun! They all smile at you and say how great you are. And you don't achieve anything, except momentary bliss for you and the audience. But, um, yeah-- Jonah Goldberg: But you also convince the audience that purity is the highest ideal. Not persuasion. Which is not politics. It's populism. Right? It's radical commitment to a single principle. And, you get this thing where politicians have the same problem, particularly on the Right, where they just talk to audiences that reinforce their most extreme positions; and politicians and pundits, particularly younger than me on the Right--they don't care any more about persuading people on the other side to change their mind. And that, in a political sense, is the essence of tribalism: It's just a hammer-and-tongs fight; it's no longer about democracy; it's no longer about persuasion. And that's a real, dangerous problem. |

| 53:20 | Russ Roberts: So, I'm going to come back to this question I asked earlier: Why is that--that was a problem in 1789. It was a problem in 1850. It's a problem in 1970. Why is it somehow--why is it rearing its head today? In a way that it didn't, in--I mean, I'm more of a libertarian than you are, but we're both--and I'm older than you. So most of my adult life, and a good chunk of yours, you're on the wrong side. You're just losing; your ideas don't have a chance. And you live with it. And wish. There's a trend; in my case the trend is the government is getting bigger and I wish it weren't. But, when I have to be honest with myself, I have to admit that: It's true that government is bigger than it was in, say, 1972, when I was 18 years old. But, America is a pretty great place; and I think the numbers are much better than people say about how the middle class is doing and poor people are doing. I think we're immensely more prosperous--not just the top 1%; not just the top 20%; not just the top half--than we were then. So, all that regulation, all that growth of government that my side's been worried about turned out pretty well. I wish it could be better. But it's pretty good. I think it's actually worse for poor people. I think they have fewer chances to flourish and express themselves, because of those regulations, because of the size of government. I don't think government helps them. I think it actually hurts them. But, reasonable people disagree with me. And I'm okay with that. But, why all of a sudden does it seem, not just, 'Well, I'm losing, as always,' but now it's not just that I'm losing. It's that maybe the very fundamentals of the system are at risk. How did we get here, in the last, let's say, 40 years? In other words, sure, there's a--I'll say it this way: Through most of my lifetime, the interventionists, the top-down folks, have had the moral high ground. My side's been losing the moral high ground--forever. Those of us who are classical liberals. So, it's still true: it was true then, it's true now. But now it seems like something else is going off the rails. And if that's true--which I think you agree--why? Why now? What happened? Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. Again, I think the erosion of civil society has been a big part of it. I personally like--I'm personally pretty invested in the plus-side of immigration. But, as George Borjas said on this podcast: you know, there are social consequences that come with it that, simply because of a libertarian or sort of patriotic bent are unpleasant to hear doesn't change the fact that it's true: That large numbers of immigrants all around the world help fuel populist backlashes. Including things like Brexit. And the data is like pretty settled on this, because people feel like they are losing a sense of belonging in their own community. And so, populism, or immigration is a big driver of some of this. But, at the top level, part of the problem is: The Founders never would have dreamed--and this is just baffling to me, because the whole thing, we were talking earlier about, how the Founders thought about, were concerned about concentrated power, arbitrary power, and that power needed to be channeled and used in proper ways, and even kept from the majority because the majority with power could be just as dangerous as the minority with power, with arbitrary power--the Founders never would have dreamed that the branches of government wouldn't be jealous guardians of their own power. I am so disgusted with so much of Congress. Which, you know--recently there was this thing where Jeff Sessions floated the idea that he might not--this is the Attorney General--floated the idea that he might not continue the Obama Administration policy of looking the other way on marijuana in the states. And this is not a point about public policy--whatever you think about the pot thing, that's different. You had Congressmen freaking out, screaming that, 'No, no. The Executive Branch has to restore this executive order.' And they were talking as if legislators had no power to write laws of any kind. Russ Roberts: Right. Jonah Goldberg: They all want to be pundits. They all want to have their spot on "Morning Joe" or "Fox and Friends". They want to opine rather than actually do the work of legislating. And the same thing goes for the Executive Branch. I mean, one the things I actually like about Trump--I may not like the motives for it--is: He's trying to give all this stuff back to Congress. But Congress doesn't want it. Russ Roberts: They don't want it, yeah. Jonah Goldberg: And meanwhile, the Judges, they want to be like the Executive Branch or the Legislative Branch, but they don't want to be like the Judicial Branch. And, there's this fascinating sort of breakdown about the Constitutional structure, where no one could have anticipated the idea that political leaders wouldn't want to, you know, get as much power and hold onto their rightful power as possible. That is part of the problem. And I think a part of it is the corruption of television and mass media, where these guys know they can keep their jobs by having a better media campaign than writing good legislation. And I don't know how you fix that. But that seems to be a big part of it. |

| 58:45 | Russ Roberts: Yeah. We're getting near the end of our conversation. I want to shift gears radically away from this for a minute, what we've been talking about, because I think--I want to get your comment on this. You say something very, I think profound: at one point, you say, "Capitalism cannot provide meaning, spirituality, or sense of belonging. Those things are upstream of capitalism." And, well, first elaborate on that. What do you mean by that? Jonah Goldberg: I think capitalism--and I think we mean, by capitalism, the same thing--free market, liberal democracy--like, the--'capitalism' has too much negative connotation, but it's the word we have. Capitalism is the greatest cooperative system for maximizing prosperity and peace ever conceived of. It just has one drawback-- Russ Roberts: Well, not 'conceived of.' Actually-- Jonah Goldberg: Well, that has emerged. Right. Right. It doesn't feel like it. It's like, Ivory Soap: It's 99 and 44/100 percent pure. I'm a big fan of the "I, Pencil," Leonard Read stuff. And, the cooperation that goes into making a pencil is mindboggling. But, it's so seamless and invisible, it doesn't feel like cooperation. Russ Roberts: Yup. Jonah Goldberg: And, cooperation is much more a hands-on, grass-roots, close live-around[?] thing. We get meaning in our lives from the people around us, the institutions that we're part of. And capitalism--capitalism can provide opportunities for that. But capitalism itself can't. There's nothing in it that, you know, fills the holes in one's soul. What fills the holes in your soul are family, faith, friends, experience, making a meaningful contribution--this notion of earned success. Those are the things that make you feel like you had a life well lived. Capitalism is great because it provides, or can provide, more opportunities to find that niche in the ecosystem that gives you meaning than other systems can. But the capitalism itself isn't doing it. It's these other things. And, as people retreat from those things, they start looking to create political systems that they think will be substitutes for that. And, the problem is that it's Fool's Gold. Socialism can't do that. Communism can't do that. Capitalism can't do that. The only things that can fill the hole in your soul are basically in the microcosm, not in the macrocosm. Russ Roberts: So, the Left's response, I think, to that, one of the responses they would say, is that: 'Oh, you are romanticizing capitalism. In fact, it's a dreary system that grinds down the worker. It grinds down the poor. It enables the wealthy and powerful to lead pleasant lives at the expense of others by exploiting them.' So, they would argue it's not upstream of capitalism: Capitalism is the problem. How would you respond to that? Jonah Goldberg: Ahhh, I mean, a lot of different ways. At least some of the same ways I think you would. One is, is that-- Russ Roberts: As the host, I get to ask the questions. I don't know the answer to them. It's a fantastic gig. Jonah Goldberg: Heh, huh, hmm. Well, first of all, if capitalism--first of all, there's all sorts of empirical ways to answer it, which is, you know, insofar as if capitalism is inherently exploitative or exploiting of people, why has the amount of leisure time that everybody enjoys continually risen? You know: Why are child labor laws lagging rather than leading indicators about the end of child labor? Why has it, why was it in capitalist countries that we saw everything from the end of slavery to the rise of civil rights, the rise of feminism, and all these kinds of things? Capitalism allows for all of that kind of stuff. It also just simply allows people more options to choose the kind of life that they want to live. The problem is, is that, you still need other--you know, other mediating institutions. To fill the void. And this is where Schumpeter, I think, plays an important role. Capitalism--capitalism is a problem, at least in the sense, in Schumpeter's telling, that capitalism is relentlessly rational. And it provides no--what he calls, no extra meaning or substance. That has to come from someplace else. And the family plays an enormously important role in that, that gives--family is the first institution of civilization because it's the one that explains to children their place in the universe. You know, Hannah Arendt has this great line where she says: 'Every generation, Western civilization is invaded barbarians. We call them "children."' And, that's true. And, families are the first line of defense against the barbarian invasion. They civilize babies into human beings, and then citizens. And then, schools play that function. And local community organizations play that function. And if they fail, the state can't fix them. And neither can capitalism. And one of the things that those kids who are not properly socialized--and this goes for rich people, too; I mean, rich people are a bigger part of the problem in my telling than poor people in terms of antipathy to capitalism--they will be filled with a sense of ingratitude about what came before them. And, they will start making arguments, you know, in the McCloskey sense: They will start marshaling words. This is something that Schumpeter got from Nietzsche in the Genealogy of Morals, is this idea that basically the priests will come forward; and the priests had no real power in olden days. But they had words. And they had arguments. And, what they would do, is they would make all those things that were once considered virtuous into vices. And that's what a lot of the sort of idea-merchants of today do, where they say getting rich is evil. Where they say democracy is a problem. Where they say freedom is a problem. Where they say that the story of America is a problem--that we shouldn't be proud of America; we should reject it. That's why you get identity politics the way that we do. And to a large extent, that's why the Right is surrendering to identity politics, which breaks my heart. And, this is--and the only solution to these problems, or to those arguments, is to come back with better arguments. And not just at the level of college debates, but in your own family. And in your own communities. Explain to people why they should be grateful that they are born in this age. I mean, I have my problems with the Veil of Ignorance, the-- Russ Roberts: That's John Rawls-- Jonah Goldberg: The Rawls. I have some problems with it. But, as Barack Obama--and again, I find it strange I'm agreeing with Barack Obama a lot on this--but, you know, Barack Obama basically used a Rawlsian argument; said that: If you were going to pick any time in all of human history to be born--you didn't know if you were going to be black or white, or gay or straight, or male or female, or rich or poor, you would want to be born right now. And you'd probably want to be born in America. And, I think that's true. We don't teach people that. We don't teach them to be grateful for the moment they are born in. And we don't teach them to be grateful for the sacrifices that created this glorious country and this glorious way of life, in the first place. Instead, we have an entire industry dedicated to resenting what we have. And I think that's the real threat. |

| 1:06:29 | Russ Roberts: Well, that's--let me just try to respond to that, because it stimulates a lot of thinking. The libertarian in me--you are a conservative; I think I'm more libertarian than you are. I'm pretty sure of that. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah--[?] more [?] direction more than your [?] and mine. Russ Roberts: Yeah; well, I'm not sure. I find myself pulling in all kinds of directions these days. The libertarian, when he says: A lot of these trends and a lot of the problem we have about the holes in the soul come from cultural forces that are hard to "can't be controlled." Many of which have a huge up-side. Which are, the celebration of the individual, the celebration of the pursuit of happiness. And, the Left--the Left--the libertarian part of the Left, celebrates that. It says: You should be free to enjoy yourself; we need to get rid of these stigmas around various cultural issues. And there have been many beautiful and wonderful things about that. One of the consequences of that, though, has been, I think, very close to the death of the family. Not the death; but it's very ill. I just looked up a piece of data the other day--because you hear all the time you need two incomes to make ends meet in America, now. Between 1980 and 2014, the number of households with 2 or more earners fell. That's despite the fact that labor force participation of women continued to rise over that, most of that period. And, the reason it fell is that people just aren't getting married as much. They are more likely to live alone. We're more likely to pursue our own happiness and not give it up for a family, give it up for, sustain a marriage that's failing or mediocre. We look for something better. And there's a beautiful upside to that. The downside is that most people don't--a lot of people feel like suckers, staying in a marriage that is not exciting, disappointing, whatever it is. The children, whether the children pay a price for it or not, Social Science debates. But, the Civil Society institutions, whose loss you decry and whose loss saddens me as well, or whose diminution, diminuition--I don't know how to pronounce it--you and I-- Jonah Goldberg: Erosion. Decline. Russ Roberts: Erosion. Decline. You and I both decry those. But they are partly the result of factors that have led to many good things. And the question is whether--for me--you know, it's easy to fall into this paranoia that runs through your book and runs through my head. Which is: 'Yeah, maybe the whole thing's going to come tumbling down.' It's not just, 'It's not going to be as good as I like.' The whole, what I would call the American experiment--this confluence of free markets and liberal democracy which is unparalleled in human history--it is the miracle that you talk about--that that's literally at risk. And if you feel that way, you have to start asking what to do about it. And what you just said is, my natural response is, well, and I don't know, and it's not a very satisfying one. Because you can't make people believe in God. You can't decree it. You can't decree that people should be more respectful of their family because it has societal consequences when it breaks down. Those genies--I don't think we can put them back in the bottle. Those of us who live a religious life can encourage people to explore it. But, public policy is not headed in that direction. So when you ask, 'What can you do about it?' I'm with you. What I try to do about it is talk about it on EconTalk. Teach my kids. Encourage other people to teach their kids. But, that's a pretty thin--I don't know if that's going to make it. You know? It's not--selling that solution is--it reminds me of a movie I love called Start the Revolution Without Me, where this one person is trying to stop--[?] obvious[?]--'It's a mistake,' and the mob is just streaming past. It's like you and I are standing athwart history saying, 'You know, it would be really good if you, when you raise your kids, to explain to them this is a special time.' And, yeah, we could write a couple of books. You've written a book, I've written some books, that talk about these issues. We need a lot more people writing books, or it's just going to be--we're going to awfully lonely. I don't think it's going to be enough. But that's all I can do. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah, but-- Russ Roberts: So, I'm doing it. But I have to be pretty pessimistic about the future in this story. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah, but I--I didn't expect to circle around you on the optimistic side. But-- Russ Roberts: Go for it. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. The--first of all, you are doing what you can do. And it's not just books, right? It's the Hayek rap video, and "A Wonderful Loaf," and it's all those great things. And you make your arguments where you can and when you can. And you do what you can. And I always tell people the fight for liberty begins in your own backyard. And, you know, the fact that it is unsatisfying that we don't have a better sort of silver-bullet answer for how to fix these things--well, part of the problem is that, as a sort of libertarian-minded conservative, or conservative-minded libertarian--part of our whole worldview is supposed to be opposed to silver-bullet arguments. Russ Roberts: Yep. Yep. Don't look to Washington to fix our problems. Washington is the problem. You've got challenge their--that's my-- Jonah Goldberg: Yeah, that's right-- Russ Roberts: That's my challenge to my libertarian friends who say 'Don't vote. Policy is a cesspool. Don't dirty yourself with it.' I'm thinking: 'Yeah, that's--I'm all for that.' I don't want my kids to go into politics. I'd be horrified, in general. But, if we don't, the other folks are going to take charge. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. But, you know, part of it is--you know--I'm one of these believers who thinks, I think you said earlier you've always been losing in a lot of these arguments. I think that's okay. You know--I feel like Hyman Roth in Godfather 2: 'This is the business we have chosen.' Right? And this is a good and glorious thing, to be on the right side of this amazing fight, right? It's a sort of a Henry the 5th [Henry V] thing: 'We happy few.' We're on the side of liberty; we're on the side of the sovereignty of the individual; we're on the side of fighting poverty. And we've been given this unbelievable gift of being able to make a fairly nice living making arguments for something that we love and that we consider valuable and important. And, I'm a huge opponent--which I wasn't, sort of going into this book--against all forms of teleology, all arguments about the right side of history. There is no right side of history. There is no teleology. Nothing is fore-ordained. We got into this world by accident; and the glory of that fact means that we can stay in here if we fight the good fight. And that doesn't necessarily mean arguments about whether the size of government should be 19% of GDP [Gross Domestic Product] or 24% of GDP. It has to do with these more fundamental things about what human liberty and human flourishing and human happiness mean and require. And, the simple fact that we're outnumbered should make it more fun. Right? You should be more of a happy warrior, because there's nothing like having a good cause--so long as no one shoots us, right? [?]-- Russ Roberts: As long as we're not in the Gulag, yeah. Jonah Goldberg: Yeah. But, until then, it's a pretty great life to make a living being paid to make arguments about protecting this glorious and wonderful miracle. I think that's--that's an important thing. Russ Roberts: 11433 Yeah; you could argue that it's the ultimate First World problem: I'm pessimistic[?] about the future while I'm being compensated wildly above my wildest dreams. |

| 1:14:44 | Russ Roberts: When I do get pessimistic I often think of the tome[?s.b. mot?], but where it says, 'It's not up to you to finish the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.' And that's my attitude. Right? We do what we can. But it does raise the possibility, and I'm curious if you've thought about this: I think you are a little bit homeless--that's my take, as a loyal follower of you on Twitter. You feel estranged from the party that--I'm not a partisan; I've never considered myself a Republican, or a Democrat, or even much of a Libertarian as a political party. But, you are a Republican historically, and you don't feel at home there so much right now. Are people talking in your spheres about starting a political party that would be more conservative and less--more traditionally conservative and less populist? Jonah Goldberg: People talk about it. You know--Richard Hofstadter had the famous line about third parties, which is, 'Historically they are like bees. They have their effect by stinging, and then they die.' And, I would have no problem joining some other party. You're right that I've always called myself a Republican by default, because it's the more conservative of the two parties. But I always took more pride in calling myself conservative. And even now, we're seeing what it means to be called a conservative being twisted around, which is why I may have to retreat into classical liberal or something. Russ Roberts: It's not a retreat, Jonah. It's a step forward. Jonah Goldberg: Well, actually, I'd prefer 'Old Whig,' which is what Hayek and Burke called themselves. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Too obscure right now. You could try to popularize it. Jonah Goldberg: A Neo-Whig. Russ Roberts: Yeah. Jonah Goldberg: But, I get asked this all the time: Am I ideologically homeless? And I'm not ideologically homeless. I'm politically homeless. I'm more ideologically grounded than I've ever been. And, this moment has been a really remarkable sort of dye-marker about--like, and people have surprised me in both directions, about people who I always kind of thought were just sort of essentially political entertainers, who have proven to actually be full of principle and conviction. And there are people who I thought who were over-brimming--perhaps too much--with some principle and conviction who turned out that it was more of a schtick. And, that's been an important lesson. But, you know, my attitude toward practical politics--you know, I've got to write about it because I'm a syndicated columnist, and all that kind of stuff--I don't actually like getting to know politicians. My attitude towards them is a lot like research scientists towards their lab animals. You know, you don't want to get too attached. And you certainly don't want to give 'em names, right? Because it's much easier to stick a needle in Test Subject 14b than in Fluffy. And, I feel that, tangibly, when I get to know politicians and become friendly with them, that's corrupting. Right? It's getting back to human nature. Friendship is, in the macrocosm, is inherently corrupting. My dad always used to say: The most corrupting thing in journalism,--my dad was in the journalism business--wasn't money. It was friendship. If a friend called you and asked for a favor, it's very hard to say no. If a stranger called you and offered you $10,000 to do something that violated your morals, you'd say, 'Get the hell out of here.' And, so, one of the things I feel tangibly every day in all of this is, people--and I'm guilty of it, too, where I take the corrupting or the malign effect of this political moment, where people are changing their positions--I take it personally. And I probably shouldn't. And I feel--I've lost some friendships. And I see friends taking my position, and taking it personally. And that's been hard to sort of separate the wheat from the chaff, intellectually, about. But--and it's a bit of a digression--but, I'm not interested in forming a party. If a party that has a chance of doing something positive started to form, I would probably write about it positively. But, that's not, it's not my gig. I'm too close to politicians as it is. I don't want to act like one. Russ Roberts: Yeah, no. It's a big challenge, because it's like: 'Well, I don't like these teams. But that team's a good team. That's a good one. I want to be on that one.' And it does--that--I think, one of the lessons I think of this world we're in, and I encourage all listeners to be aware of this, is how tribal we are. And to see if you can be, find that Adam-Smith/impartial-spectator to see it in yourself, in our eagerness to see 'our team.' And, you know, I love it when people complain about an EconTalk episode and often it's because they didn't like the politics or the ideology of the person, and nothing to do with whether it was good or not. But, they just-- Jonah Goldberg: You'll get some of that on this one, I promise. Russ Roberts: We might. Yeah. 'That was a waste of time.' And I also, I'll get criticized for agreeing with you so much. So I apologize to listeners who expect me to give you a harder time. I am very sympathetic to a lot of the arguments, which made this a different--more of a conversation and less of a challenging set of questions. |