| 0:36 | Intro. Why are there firms? Firms are almost anti-market, paradox. Markets organize people's activities. Prices are a way of organizing activities of people who may be acting on their own; prices allow people to achieve their goals. Recent increase in corn exported by Brazil not as a function of any Brazilian policy, but as a consequence of U.S. decision to use corn for ethanol, which increased world price of corn. Munger gave an explanation for why corn price went up, but actually nobody knows why. We know how the change in one thing can affect other things but reverse isn't true--we can't infer the cause from seeing the effect. Price of corn goes up by less than it would have, had Brazilian farmers not reacted. Price does the leading. Adam Smith quote: Individuals are led, as if by an invisible hand. Paradox: Most economic activity in developed economies isn't led by price at all. It's led by some boss. Command and control. People are led by explicit directions of their bosses. Soviet Union, "I've seen the future and it works," dispensed with prices and profits, someone in charge instead of chaos. Economic debate, F. A. Hayek: socialist calculation could never mimic what prices do no matter how great the computer power; Abba Lerner: with right set of equations you could in principle replicate what prices or perhaps do even better by satisfying social needs or justice. |

| 8:37 | People anthropomorphize the market. People "are led" by the invisible hand, the market, as if it is an individual. Plans are deeply appealing. Agency issue, it seems better to do things intentionally than just hoping it will come out okay. For individuals, plans are how you get things done. Spontaneous emergence doesn't happen for individuals, can't rely on the invisible hand to do the dishes. Third factor: We would like this anthropomorphic thing to have our best interests at heart, to have the right motives. Want people around you to care about you. But, as Smith points out, ironically, when the butcher cares most about himself you get the best meat, lowest price. But not necessarily for a "plan." Prices are forecasts about the future. Only in a market system is it possible to plan, is what Hayek and Mises were claiming: you need the information that prices give you about scarcity. |

| 12:53 | Paradox: The defenders of markets, going back before Smith to Ferguson, despite that elegant and powerful system, an enormous amount of economic activity takes place in centralized organizations--firms, non-profits, etc. People within these units allocate time and energy not by prices but via a centralized leader. It appears that they are not using the power of prices. Odd that in order to make profits you have to suppress the market mechanism. Dilbert Principle: Promote the least competent people into management where they can do the least harm. Why would you think the manager knows more? We've argued that a government can't know enough to accomplish it, how can a manager? Marginal productivity is not measured, merely guessed at. Wisdom of the leader, services like desks or computers are given away within the firm. Discipline to achieve is from hiring and firing, or bankruptcy. IT department of a university or firm has to decide how many computers to have; it's decided by fiat, not by market but by political jostling over the budget within the university or firm. Unintuitive for those who argue for the virtues of markets. Though lots of firms do try to introduce market mechanisms such as stock options, market divisions within firms. But most internal decisions apparently are not based on prices. Macy's--how many shoes should you carry, how much space should you devote to shoes as opposed to cosmetics? Why not rent the space to a shoe seller, the highest bidder for the space? |

| 20:34 | Is the answer that Macy's way is better merely because we observe them doing it? Department chairman or boss is often humorously described as the herder of cats. In actuality, the boss can't just decide to devote half of Macy's to shoes or they'll go out of business. Determined by competition between Macy's and other stores. Alchian. Might have happened originally by luck, but if you come back in a hundred years and see that they have survived, you know it's worked. Through attrition and expansion of firms, unsuccessful firms get weeded out. Manager and owner are the same person, small firm, owner has incentive to find out how much space should be devoted to shoes. It's not that everybody optimizes, but that everybody who survives managed to optimize. Shopping malls: malls, in contrast to department stores, are weird. Macy's is a centralized mini-mall, but within the mall Macy's sits in are firms following a different model, individual shoe stores, very specialized, who will get thrown out of the mall if they fail. Macy's and the individual shoe stores coexist. A mall is price-driven. Consumers are using the price system, though, comparison shopping. An economist persuaded by this might say that Macy's costs are going to be higher, so you should go to these individual stores who live or die by their choices. Where should you go shopping for produce in the former Soviet Union if you had the money? The black market, not the state-owned shops. |

| 28:52 | Something else must be going on in these situations that makes up for the inefficiency of centralized allocation of goods and people within firms. It more than makes up for it, since in terms of sales and retail most things are done in firms. Janitorial services: could outsource (subcontract to another company) it completely and hire an outside firm; why not also accounting and computer maintenance too? Take bids up front. How can you be a good judge of all those individuals? Just outsource, will have more information. Out of house, incentivize. Six weeks later profits up, stock price up. What about other employees, builders, shipping department, why not contract for all those services? Save extra money for time wasted when nothing to do. Why not even sell the buildings and rent? Put on my bunny slippers and wait for the huge increase in profits and the bonus to come up. 400 emails: I haven't anticipated all the contingencies; my main supplier hasn't delivered. But he doesn't know who I am when I ask him what's going on. He's not my employee, but a subcontractor and I'm just another of his clients. Now I've got to establish personal relationships with hundreds of people and companies in order to handle all kinds of contingencies. I can't write contracts that specify all the contingencies. My contract is simpler: You come to work every day, and minute-by-minute I can change what you do. |

| 37:41 | 1937 Ronald Coase article (71 years ago) saying that it's dramatically more efficient to do this. Transactions costs. It's not free to use the price system. Firms exist when it's too expensive to use the price system. Home repair or home improvement: invite someone into your house, their bid never turns out to be what you pay, always surprises. Some you pay by the hour; but that gives them an incentive to go slowly. Maybe best way is flat rate; but you rejected the high bidder who may have anticipated that and now you are stuck with uncomfortable situation and maybe having to pay more. Willing to pay a little extra to not have to monitor. Just getting the bids is costly, and comparing different bids is costly. Firms economize on transactions costs, foregoing the benefits of the price system, using centralized economic activity internally. Plenty of competition among the firms, so consumers still get the benefits of competition. Mixed economy in the sense that there are numerous organizations with top-down structure which are all competing with each other. |

| 45:20 | Pin factory example. Division of labor dramatically reduces costs. Imagine pure market pin factory, subcontracted. You don't really decide what to pay your employees, even though it looks that way. What you pay is determined by the market for pin sharpeners and price of pins. Suppose you pay each pin sharpener a little extra because you are a nice boss. Disciplined by the final consumer price; workers are disciplined by competition for their services. Owner/manager (easiest to think of them as the same person)--people who are good at that are those who are good at monitoring and understanding these processes without the benefit of prices. Very hard skill. |

| 50:46 | Challenge of doing this outside of a simple process like pin manufacture, services. No tangible, visible, observable, measurable forms. Team production. Alchian and Demsetz, 1973. Monitor, specialized position, has most important function. Extension of division of labor. Can just use piecework for pins, bunny-slippered boss just says "Give me a call if something goes wrong." China, group of workers had to pull a barge up the Yangtze River, upstream, 10-15 guys. Insight of team production problem is that you need division of labor, a monitor, to watch that the others are doing good-enough work. Cheung paper: the coolies themselves hired the monitor with the whip! The man with the whip is your conscience; but with many people involved may want to hire a conscience. I'm happy to pay something to be disciplined because I will make more by working harder, though ideally I never get whipped but merely respond to the incentive. Seems to be a waste. One-person barges inefficient. Tension between different incentive structures. Could just pull barges with people you like, say your family. Munger and Sons Barge Pulling. Historically common, but even family members shirk. "Cain was not able to solve this problem." |

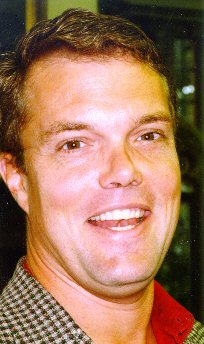

Mike Munger, of Duke University, talks about why firms exist. If prices and markets work so well (and they do) in steering economic resources, then why does so much economic activity take place within organizations that use command-and-control, top-down, centralized structures called firms? Within a firm, most of the goods and services that the workers use are given away rather than allocated by prices--computer services, legal services and almost everything else is not handed out by competition but by fiat, decided by a boss. A firm, the lynchpin of capitalism, is run like something akin to a centrally planned economy. Munger's answer, drawing on work of Ronald Coase, is a fascinating look at the often unseen costs of making various types of economic decisions. The result is a set of fascinating insights into why firms exist and why they do what they do.

Mike Munger, of Duke University, talks about why firms exist. If prices and markets work so well (and they do) in steering economic resources, then why does so much economic activity take place within organizations that use command-and-control, top-down, centralized structures called firms? Within a firm, most of the goods and services that the workers use are given away rather than allocated by prices--computer services, legal services and almost everything else is not handed out by competition but by fiat, decided by a boss. A firm, the lynchpin of capitalism, is run like something akin to a centrally planned economy. Munger's answer, drawing on work of Ronald Coase, is a fascinating look at the often unseen costs of making various types of economic decisions. The result is a set of fascinating insights into why firms exist and why they do what they do.

READER COMMENTS

Bruce Boston

Jan 14 2008 at 3:03pm

Hi Russ, yet another great podcast!

I’ve had a similar discussion with a number of people over the years on this.

Being in business and watching things over the years, certainly transaction costs is a major part of this. One concern I have with the Transaction Cost Theory is that I see no reason why you couldn’t outsource the transactions. I guess you could say that it ‘just doesn’t work’ which is a reasonable reason for something to not exist, but it doesn’t feel like the whole picture is all here.

That said, what this really brings out that simply because a ‘cost’ isn’t being measured, it doesn’t mean that the cost doesn’t exist. In a similar way, I wonder if that just because a given ‘value’ isn’t being measured, it doesn’t mean that the ‘value’ doesn’t exist.

Over the years, I have worked as a contractor, and as a ‘self-employed’ person, and in small companies, and start-ups and now in a large company. I also have the skill set that allows me to work in any of these areas today, ie I have the choice, but I choose the large firm.

What I think is interesting is that I really enjoy working in the ‘large firm’. Even though my annual take might be higher in one of these other forms of employment, which suggesting that ‘salary’ is only one of the factors that I’m using to decide my workplace.

This got me thinking. In that, I think I’ve always been taught that most of the value that a firm creates is on the ‘product/consumer’ side of the equation. But, I wonder if firms don’t also create value for the employee.

How would this show up? Well, if the intangible value of ‘working for a large firm’ were higher than the intangible value of ‘working as a contractor’, then you’d expect that the cost of hiring a contractor would be higher than the cost of hiring a full time employee. Which is the case in my field. Contractor costs are much higher than full time employee costs.

So, then the next question arises, what are some of the intangibles that employees get from firms that they don’t get from another form of employment?

Just to name a few,

1) I like the fact that I work for a well-known recognizable brand, I get ‘social currency’ from this.

2) I like working with the same people everyday, with one or two changes here or there.

3) I like the lower risk that ‘firms’ offer.

4) I like the problems that larger firms have to offer.

5) I like the ease of access to resources that larger firms have, if I need a new piece of equipment, its easy to get.

6) I like the degree of specialization that I get from working in a large firm, 99% of where I spend my time in in my specialty, and as a result, I progress faster in it.

7) I like the work environment, in the start-up we were in an old building that was pretty run down.

8) I like the degree os ‘professionalism’ inside the company, HR does a great job of screening people that become my co-workers.

9) I even like the quality of management, as the larger firms have the capital to attract higher quality talent.

10) I like the benefit package that the firm offers.

11) etc, etc, etc..

All of these factors went into my decision to join the larger firm, and is part of many people’s decision to do so as well.

So, again, just looking at my own life, while the value that the ‘firms’ produce for the consumer side of my life (where I spend half my time) is important and being optimized by markets, I also wonder if markets aren’t also optimizing the value that that ‘firms’ produce for the other half of my life. Which suggests that to get a full picture of the total value that ‘firms’ are producing you’d have to have a calculation that included both sides of the equation.

Again, as a conclusion, I’m wondering if the increases in value created on the employee side of the equation don’t more than make up for the loss of value on the consumer side caused by the apparent inefficiency of the centralized command structure of firms. Stated another way, perhaps the competitive advantages gained in the labor market by the firm structure, more than make up for the expected inefficiencies of that structure.

-bruce

Scott Anderson

Jan 14 2008 at 3:19pm

Excellent topic! I stumbled on transaction cost economics in grad school while writing a paper about channel strategy. The topic seems to be at the center of strategy (five forces) and business model development.

One comment: I am amazed at the hiring and promotion practices of some firms. These practices, particularily in areas that require some skill/talent are of major importance to a firms well being yet I see time and again extremely qualified people being downsized, often the wrong ones, then taking a very long time to be hired and then being underemployed. Employees often have high transaction costs too, sometimes almost insurmountable to make a change to a different employer.

Allocating capital has made our economic system so much more efficient and effective than the socialist type, maybe won the cold war. Allocating human talent to task must be as important in today’s world yet it seems that many firms are not doing a good job. Transaction costs may be a barrier but talented people tend to be profit centers of new ideas, sales and contacts, so perhaps the market hasn’t yet fully priced in the value on the revenue side (because of the transaction cost frictions?).

By the way, Macy’s is trading at below book value. Earnings are less than $700 /per employee, an often used measure of human capital and debt is on the rise.

Russ Roberts

Jan 14 2008 at 4:45pm

About half way through this podcast, I raise the example of how hard it is for a department store to compete with the various stores in mall that carry similar merchandise. The shoe store has to live and die selling shoes. They have to cover their costs including rent or go out of business. The department store in the same mall has much less precise information on how its shoe department is doing. It has to impute a rent. It provides without charge the accounting and other services shared by all the sections within the store.

So how does a department store compete? How does the business model of a department store survive?

I promised to come back to this question. But I forgot to. I’ll give my answer eventually, either in a future podcast or down below. But in the meanwhile, feel free to listen to the podcast and provide an answer of your own.

Dick King

Jan 14 2008 at 9:02pm

You did promise us middle-of-the-week bonus podcasts from time to time…

-dk

Unit

Jan 14 2008 at 9:03pm

Maybe a dept. store competes by trapping the costumers in its maze-like lay-out. This increases the costumers’ transaction costs in trying to get the best deals, hence gives them an incentive to do all their shopping in a single store.

Also an employee of a larger firm might accumulate firm-specific knowledge over time, this can save time and money. On the other hand, such gains might evaporate when it becomes time for the employee to leave the firm: the knowledge being firm-specific may not do the newly unemployed worker any good, on the other hand, the firm will have a harder time replacing such a valuable worker.

Ben Rast

Jan 14 2008 at 9:44pm

Perhaps firms are nothing more than voluntary tribes, a concept consistent with human evolutionary history.

Tribes are not organized on the basis of prices. They are organized to serve the various purposes of the individuals in the tribe. In effect, tribes are a temporary overlapping of individual self-interest. The same is true of firms.

The difference is that firms give individuals the option to leave, if they think they can find a better deal in another group.

Thus, it comes no surprise that individuals, rationally seeking their own purposes and driven by the common needs of human nature, seek first to join a successful tribe (company) rather than investing time and effort in starting something new. After all, interpreting the information in prices is not an easy job. Some people would rather let someone else assume that responsibility and that risk.

It is not the search for benevolence that draws employees to a firm. It is the opportunity to serve their self interest.

Of course, the same is true of the entrepreneur who created the firm in the first place.

Richard Sprague

Jan 14 2008 at 9:53pm

Another fine podcast. Followup question:

Why doesn’t the same logic extend upward, to governments and command-driven economies?

So if transaction costs are the reason the Firm is sometimes better than piecemeal producers, why (in theory) can’t a socialized government beat a capitalist economy? Surely there are plenty of transaction costs in society too that could be saved.

Russ Roberts

Jan 14 2008 at 10:09pm

Richard Sprague,

In theory, you’re right. But Hayek and others argued that the informational problem was too overwhelming. See The Road to Serfdom. Or The Fatal Conceit. There’s also the rather large problem of incentives. Why would you expect a socialized government to strive for efficiency? A loving parent can do a pretty good job as an autocrat figuring out what’s best for the children without having to auction off the cookies when there aren’t enough to go around. But an autocrat who rules a society doesn’t have enough love to get the job done. In fact, historically, the opposite has been the case. Too much self-love.

John Phillips

Jan 15 2008 at 3:03am

“So how does a department store compete? How does the business model of a department store survive?”

I’ll take three stabs at why this occurs.

1. Economies of Scale: Macy’s is in many locations while the Niche player is likely in fewer. So, Macy’s (potentially) has more buying power than many Niche shoe sellers. Neither Macy’s or Niche shoe seller are making every sub component for their shoes. They contract out for labor, floor time at manufacturing facilities, transportation costs and because Macy’s can muster more demand they then get to demand lower prices for these components. Essentially, the shoes themselves are not pure commodities because they will always cost Macy’s less to obtain in the first place. So even if Macy’s has inefficient pricing to the customer they could conceivably still be lower prices than Niche’s due to lower back end costs. (Walmart for example can put “Always Low Prices” in costly fixed letters on its storefronts because their buyers can negotiate lower prices due to massive volume.)

2. Diversification: Markets are cyclical, even the markets for shoes, perfume, clothes, etc. Maybe one year perfumes sell at a markup, while other years the hot item is shoes. What Macy’s can do in order to make use of this phenomenon is diversify its ‘porfolio’ of products in order to ride the wave of high demand goods (increase floor space given to the hot product, decrease space for the low performers…which the Niche sellers (both hot product and low performer) are not able to do as well! The Niche seller of the hot product will not have the variety (more floor space at Macy’s) and the Niche seller of low performers will not be able to renegotiate Mall rent price for his low performing product because, marginally, his rent is determined by the next best alternative: another hot product seller!), thereby decreasing Macy’s overall risk of multiple bad winters and subsequent bankruptcy.

…

In fact, if Macy’s had one item that sold like hotcakes, then it could fluctuate prices around individual price points for each of its products. Either selling the hot product at a loss to draw people into the store but then selling other products at a markup assuming that implicit opportunity costs of shopping (convenience, really) would keep customers in their stores. Or the inverse of ‘expensive’ hot products and ‘inexpensive’ everything else.

(And the cynical view…)

3. Taking advantage of competitor start up costs: First an aside that will hopefully inform the rest of this bullet point…The big story about a Walmart coming to town isn’t that all the Mom and Pop stores die off, it’s that they don’t come back.

If we have two towns, Town 1 and Town 2 and each town has one Niche store, say Niche A in Town 1 and Niche B in Town 2, but both towns also have Macys then we can get some interesting phenomenon. Macy’s can lower their price below price point in one town to the point where they run Niche A out of business, then with Niche A out of the way raise prices to a level just even with or just under what would be the equivalent for a start up cost of a new reincarnated Niche A. This new price is not only above the undercut price but is now above the original price point. If Macy’s then repeats with Niche B in town 2 it can now charge a higher price in both local markets, recoup losses, and enjoy monopoly status.

Thoughts? Holes/Gaps?

Bruce Boston

Jan 15 2008 at 3:48am

Hi Russ,

Hayek’s arguments around the informational problem was based on pre-21st technology.

For example, if Walmart was a country, I think it would have a GDP that would make it something like the 30th largest country in the World. How is it that the Walmart Planners have figured out the Information Problem?

On the Incentives Problem, are we saying that large corporate incentives keep CEOs moral? Then why not make this part of Government? If throwing a few million bucks at the country’s CEO will increase her morality, shouldn’t we do that? Plus, with the public’s ability to vote government officials out, wouldn’t we have more safeguards against the officials immorality than we do with Walmart’s CEO? And, isn’t it the butcher’s greed that keeps us trusting in him?

Which, I know, leaves Competition. Except, haven’t the Walmart Planners figured out how to incorporate competition at the product level into their economy? Which includes product prices? Which then includes production quantities, product qualities, innovation incentives, and intangibles? Which only leaves competition at the Firm level, but can’t you have the Post Office and FedEx, DHL, UPS, etc, etc, etc?

I wonder if the true evil of socialized government isn’t Wealth Transfers. Due to the traditional socialized government promises of equality in output regardless of the inequality of inputs, ie, people all get paid the same regardless of their contributions. But how is the probability of wealth transfers lower in a free market system than it is in socialized governments?

Assuming that wealth transfers don’t happen in companies, Firms have figured out how to widely vary compensation across the organization, and deal with shortages, and deal with prices in a way that gets around this need. So, what makes Firm Planners smarter than Government Planners?

Second, the problem of wealth transfers is hardly a problem specific to socialized governments and clearly hasn’t been solved by our government system in any way, nor could it be solved with a free market system. How does a free market system solve the problem of wealth transfers at the government level? As long as the government has the ability to collect taxes, and politicians have the ability to make promises, and majorities have the ability to out-vote the minority in deciding how to spend the money, wealth transfers are going to happen. The fact that the government has to spend the money on outside vendors hardly fixes anything.

If all a free market system does is strip out the command and control of government and put it into Firms, and we are still left with wealth transfers at the government level, how is this really going to solve the core problems? What can we expect in this system? In good times, competition for the receipt of government wealth transfers? (which is a selfish politician’s dream) In bad times, what would make a better scapegoat than a market failure (again a selfish politician’s dream). Who better to blame for the rising costs of (fill in purpose of wealth transfer) than the Firms that out-competed everyone else in the market? A few years of this, and the public will be begging government to regulate outside firms. Regulation that will need a ‘Strong Man’ to put things in place.

And, where’s it go from there….oh yeah… the Strong Man is given power, the Strong Man’s party takes over, a Negative Aim wields party unity, etc, etc, etc. “Regulation isn’t the problem, the problem is an oil shortage in the Middle East!” No?

Oh, but you get decreases in war with a free market, right? Because its not like you can hire a firm to go fight a war for the country or anything, right?

But seriously, what problem is it again that we are trying to solve with open markets?

-bruce

Mike Munger

Jan 15 2008 at 10:15am

Lots of cool comments here; I will try to cherry pick just a few, and perhaps also try back later.

Bruce Boston: In your first comment, you actually paraphrase what I consider to be Hayek’s most powerful argument for markets. No government, no planning agency, and no firm could POSSIBLY know the answers to your good questions about tastes and abilities of the individual. Only the individual could know that. So, a system that “tracks” through education (“You have aptitude to be a blacksmith, so you must go to blacksmith school!) could match that way. Only individuals, choosing along a dozen different dimensions can hope to optimize. I can go to work for IBM, and wear a suit, or go to Apple and wear shorts and a Hawaiian shirt. Which is “better”? People sort, based on complex personal considerations of location, pay, and atmosphere. So, yes, you are right that that diversity of employment options created by firms is a really important thing that we missed.

On your second question, Bruce, in the later comment (3:48 am? What the heck?). You make a nice point about there being two quite separate arguments for markets. First, the Hayek point about information and planning. The second is the problem of transfers and theft. I think, though, that you underestimate the importance of the first. The answer is not technology, but of incentives for releasing “impacted” information (to use the Oliver Williamson phrase.) It is EXPENSIVE to know the amounts, condition, and current uses of all the many inputs into the production process. Prices summarize all of those, but only if the markets are open and free to adjust to relative scarcities. Computers cannot solve that problem, no matter how fast or enormous, because no one has an incentive to go around and collect current data. Prices adjust very fast, and there is NO OTHER WAY to get the data in time. Not a problem of PROCESSING, but of COLLECTION, of information.

The transfer point is important, and in some ways that parallels von Mises’ argument in his book BUREAUCRACY. Some people say that government should be run “more like a business.” Well, maybe, but you can’t run government like a business because it doesn’t have prices and it specializes in providing services for which the collection of fees or charges is expensive or infeasible. So, outsourcing everything will NOT really help. von Mises says that the only way to control the problems of bureaucracy is reduce the SCOPE of government itself, not to outsource services.

Michael Munger

Jan 15 2008 at 10:26am

Gavin Kennedy points out an important correction on Adam Smith’s Lost Legacy.

And, he is exactly right, as is usually the case. Worth reading.

Scott Anderson

Jan 15 2008 at 11:27am

I’ll take a stab at the question why some department stores are able to stay in business. The short answer may be search costs. Some customers are not willing to invest the time to search out individual stores for each of their needs but would rather trust the reputation (brand) of a store that provides multiple needs to a specific customer segment and minimizes the amount of search time while in the “mall within the mall” to find the bundle of goods to satify those needs.

Customers are segmented by need. Some customers want to shop only for a specific category of good and may prefer to shop at a specialized category killer kind of store. It has a large assortment of a particular category say shoes, kitchen appliances, consumer electronics, toys etc. The store often is a destination location, has deeper knowledge of the product and customer needs for the product. The search costs are minimized when for a particular category of product.

Other customers want a store that provides a diverse set of product categories with a moderate product assortment, minimal service but low prices and the convenience of finding many items in one place. Search costs are minimized to bundle several purchases and the product cost is lower as well because of the large turnover of sales and buying power of the store – think Walmart.

Other customers want to buy goods from related categories in one place that targets them as a customer segment. The department stores tend to have specialty stores within a store that carry a smaller assortment of items but items that are stocked for a specific customer segment like high end shoppers. The items have a lower turnover than at a super store but many of the items are logical bundles for a customer on a particular shopping trip (shoes, socks, suits, ties, etc.). The customer buys there because the mercahndise stocked matches their desires, shopping trips can be efficient, and there is a degree of trust regarding the quality of goods. Overall search costs are lower.

It seems that the market has moved away from department stores to specialty stores and super stores causing department stores to drop toys and appliances, move more upscale, and create more of a specialty store within in a store that targets particular segments – Think Nordstroms.

Another reason why department stores may have survived is that they are typically made of a large network that is able to experiment with various formats and products. The large network allows them to lower the cost of informatiion gathering about customer needs and then replicate good findings among the stores.

How did I do?:)

Philip Segal

Jan 15 2008 at 12:02pm

Not all the departments in a department store are owned and/or operated by the department store. For example, most cosmetic departments are separately owned. That atttractive blond who sprays perfume on your wrist at Macy’s doesn’t always work for Macy’s, which also explains why she won’t help you at a different counter. In essence these departments rent space from the store either on a fixed cost basis or a percentage of sales basis. So at least in these cases we’re back to specialization, much like the niche store in the middle of the mall.

As to the costs of bookkeeping systems, accounting, etc. These costs can be kept track of in most stores today. Since the company knows how many SKU’s are sold each day, and at what price/profit, the company can in fact charge the service costs to the departments that generate them if it wants to. Or it can call them “corporate costs” or “S,G, and A” and charge them to the profit lines for each store or division or whatever other way they want to account for them.

Much if this just goes to show that Schumpeter was right to suggest that economists should also take basic accounting classes. see McCraw on Schumpeter, Innovation, and Creative Destruction

Dick King

Jan 15 2008 at 12:22pm

Mr. Sprague, one advantage of firms over countries is that you don’t have to move and lose contact with your family to change firms, usually.

Company towns are in fact a [partial] exception to this, and in fact they have usually been associated with less-than-effective firms.

-dk

Martin Brock

Jan 15 2008 at 5:18pm

I never make it to the mall. I head straight for WalMart. If I want to go upscale, I head for Target. A few specialty superstores, like Best Buy and Barnes and Noble, occasionally attract me, and I don’t drive past Kroger to buy groceries at WalMart, but I’m very loyal otherwise.

I suppose stuff costs more at the mall, but I haven’t shopped at a mall regularly for years, so I don’t really know. If someone persuaded me otherwise, I might change my habits, but Scott is right. I need a perception of economy, but it’s mostly about convenience.

I also buy more and more online these days. That’s about convenience too, mostly the ease of making comparisons. I never really know that I’m getting “maximum value”, but I know that I like what I’m buying better than lots of options, as far as I can know from the ads and opinion peddlers.

Regarding firms, the economists imagine that efficiency and cost minimization drives everything. If they define “cost” broadly enough, I suppose it’s true, tautologically, but I suppose firms exist for many other reasons. First, people like working in groups. It’s a tribal thing and has little to do with market economics, unless everything is market economics.

Second, people who start businesses want to get rich, i.e. they want to earn more than other people. This goal is practically universal, and people usually pursue it through hierarchical authority. The people dividing the spoils pay themselves the most.

Finally, capital markets naturally concentrate wealth. It’s market efficiency and Geometric Brownian Motion. This model is simple, but its simple assumptions are tough to dispute, and empirical wealth distributions are consistent with it. GBM generates a lognormal distribution that approaches a Pareto distribution over time. Competition increases this effect rather than diminishing it, because competition increases market efficiency.

Some people have accumulations of capital to start businesses, and they organize the factors this way. That’s a simplistic explanation too, but it’s as reasonable as the idea that we’re all minimizing costs. I know I’m not always minimizing costs. I have three kids, an ex-wife and a fiancee.

Bruce Boston

Jan 16 2008 at 12:25am

Hi Michael,

I have to say, I love the topic!

Ok, in no particular order……

“No government, no planning agency, and no firm could POSSIBLY know the answers to your good questions about tastes and abilities of the individual.”

True, but we seem to be suggesting that when a Firm doesn’t know all the answers they have some sort of magic that makes their ‘lack of information’ an efficient boost, but then we also argue that government’s lack of information makes them inefficient. So, how do we tell the difference between when inefficiency is efficient, and when inefficiency is inefficient?

“You have aptitude to be a blacksmith, so you must go to blacksmith school!”

I see this often, but how is this not committing a serious Straw man Fallacy? If I understand the basic argument, it is: socialist governments that try to ‘track individuals through education’ fail, therefore all sociacialist governments fail. Implying that all socialist governments ‘track individuals’. However, not only is this not part of any current socialist practice, I don’t even think its part of current communist practice. Are there any governments that still do this? Is there anyone defending this position? If not, then either we have to conclude that socialist and communist systems don’t exist, or that ‘tracking individuals’ isn’t a necessary part of them.

“Only individuals, choosing along a dozen different dimensions can hope to optimize.”

So, I get this. What I’m not sure I understand is how individual choices optimize central-command Firms, but wouldn’t optimize central-command Government Firms? How is FedEx, UPS, DHL optimized by individual choices but not the US Post Office?

From the article “First, firms are contractual means of reducing transactions costs.”

Again, how is FedEx, UPS, DHL aided by this reduction but not the US Post Office?

Also from the article “Second, Coase argues that the optimal size of firms responds directly, though in undirected ways, to market forces.”

How are FedEx, UPS, DHL directed by market forces but not the US Post Office? Doesn’t the USPO need less employees when their prices are too high, and have too much mail when their prices are too low? I have a hard time believing that the US Post Office doesn’t use price information to set prices, or optimize services or attract their labor force. In fact, how are they able to attract the labor force they have without having to compete for the same scarce labor sources that FedEx and UPS do? Inscription? Somehow they make it through the Christmas season, no? So, how is it that we conclude that government services are immune to the benevolent forces of the market?

“First, the Hayek point about information and planning. The second is the problem of transfers and theft. I think, though, that you underestimate the importance of the first. The answer is not technology, but of incentives for releasing “impacted” information (to use the Oliver Williamson phrase.) It is EXPENSIVE to know the amounts, condition, and current uses of all the many inputs into the production process.”

So, a few things here. First, Firms don’t know ‘all’ the inputs. All they need to know is the price of the step before what they are responsible for. Second, again, even communist Chinese Planners use prices, and don’t know ‘all’ the inputs. For example, they don’t need to know all the inputs into American Wheat, they just need to know the current price to buy more, their current inventories and they adjust market prices accordingly. One concern here is that it appears we are using thought models that are so old in their assumptions that they don’t even take globalization, or governmental use of prices into account. Can we make an argument why Chinese Planners, but not Walmart Planners, will be grossly inaccurate in their planning when they place orders for imports?

“Prices summarize all of those, but only if the markets are open and free to adjust to relative scarcities.”

Costco, Walmart, Dell, Toyota all have very centralized planning, and they all have a system of passing pricing information from the producers to consumers and back again, in Dell’s case, in real-time if needed. None of these companies have stores that are either ‘open or free’. Which, lead us the the above conclusion that Firms are more efficient because they reduce their use of free and open markets, and thus their transaction costs? So, governments should aspire to open markets, so that firms can close them back up?

“Computers cannot solve that problem, no matter how fast or enormous, because no one has an incentive to go around and collect current data. Prices adjust very fast, and there is NO OTHER WAY to get the data in time. Not a problem of PROCESSING, but of COLLECTION, of information.”

Again, I see no requirement on central planners to ignore prices, the central planners of both Firms and communist countries surely use prices, as does any government agency that has budgetary limitations, which is everyone. And to bind the hands of of the government straw man while giving Firms both hands to hit with is, again, a highly bias comparison, and again, a Straw man Fallacy.

“The transfer point is important, and in some ways that parallels von Mises’ argument in his book BUREAUCRACY. Some people say that government should be run “more like a business.” Well, maybe, but you can’t run government like a business because it doesn’t have prices and it specializes in providing services for which the collection of fees or charges is expensive or infeasible. So, outsourcing everything will NOT really help. von Mises says that the only way to control the problems of bureaucracy is reduce the SCOPE of government itself, not to outsource services.”

**This is like comparing the cost/value of the pickers of the low fruit to the cost/value of the pickers of the high fruit, and concluding that the low fruit pickers would do a better job of picking the high fruit because they have a better track record.**

Why is government limited to services that don’t have prices? And, why does it specialize in providing services for which the collection of fees or charges is expensive or infeasible? Sounds like government is in the wrong businesses, might it be perhaps because business can’t make a buck in these areas? If so, do we take this into account when we evaluate the efficiency of government services? And, how is it that we are going to get industry to take over services for which the collection of fees or charges is expensive or infeasible? What magic are Firms to use to solve this? And, why isn’t this magic available to the government?

-bruce

ps, i think the time is ET, and I’m PT.

Unit

Jan 16 2008 at 9:01am

“Are there any governments that still do this?” – Bruce Boston.

Yes, China. In fact, it’s more like “you seem to be good at blacksmithing, but we need wood-choppers, so you’re going to chop wood”.

Michael Munger

Jan 16 2008 at 2:29pm

To Bruce Boston:

Are you serious?

The educational systems of Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, France, and Japan do exactly this. In order to qualify for university, you have to have been tracked for such at an early age.

If you meant literally “blacksmith,” then no. But the decision on whether a student will go to vocational or academic track is made by the sixth grade, and may be made as early as the 4th grade. A series of end of year tests are the mechanism of “choice,” not real…well…choice.

Yes, China does it to an even greater extent, but in fact this kind of choosing of career by government is absolutely common outside of the U.S. It is the NORM. Students are assigned by “aptitude” to trade schools.

The reason? University is “free,” or paid for by taxpayers. You can always go to a private school, but only the rich can afford that.

Schumpeterian

Jan 16 2008 at 10:57pm

Mike,

Interesting article. If I understand right, the theory is that firms exist to reduce transaction costs, coordinate tasks, and monitor quality.

I think by that definition, each individual person would be a firm.

Reduce transaction costs:

I did an initial search for my supplier of weekly groceries and I now return there making regular payments to them on a weekly basis. We have no written contract, but there are no further transaction costs than if we did. I chose them because they provided what I wanted. This is the same criteria I would use when hiring an employee.

Coordinate tasks:

I don’t do anything other than show up at the store, and the food is waiting for me to pick it up. All the tasks from plowing to picking to shipping were coordinated without my needing to do anything more than arriving at the agreed upon delivery point, the store.

Monitor quality:

I consume the end product or serve it to someone else. If I find I have received a bad product, I take it back to the supplier. If someone I served finds a bad product, they bring it back to me, and again I take it back to the supplier. Too many of these and I will find another grocery store. Just like too many screw-ups by an employee and I would fire that employee and hire a different one.

(I think the problem with the parable from the article is that it assumes everything goes wrong all at once. This would be similar to my credit card, car, grocery store, gas station, bank, Internet provider, cell phone, etc. all messing up at the same time. Yeah, my personal life would be in shambles too, so that doesn’t really prove that this design wouldn’t work for a firm, just that it really sucks when it happens.)

So if each individual already does the three things that the theory says firms do, then what is the firm good for?

I’m willing to pay the same for a product whether it is provided to me by a single person or through a firm. So to me that says that the consumer of the firm’s output is not the true beneficiary of the firm.

I think the true beneficiary of the firm is the worker in the firm. The worker is willing to “sell” the rights to excess profits generated by his work in exchange for an even and steady income. The firm is really in the business of selling security and stability to its workers. Well actually the firm can’t guarantee either security or stability, so they are in the business of selling the appearance of security and stability. A product that many people pay a whole lot to get. Homeland Security in exchange for your civil rights anyone?

Thoughts?

Bruce Boston

Jan 17 2008 at 3:05am

Hi Michael,

At first glance, this appeared to be a red herring fallacy response, as you have clearly left all the topical questions unanswered, but looking at this again, maybe we can steer this back on to the topic of the relative efficiencies of both Firms and Government Agencies acting within a market system.

While I am not an expert on the educational system of Japan, any more than I’m an expert on the educational system of America, I’m somewhat a product of that system, having lived in Japan for 6 short years, part of which to attend school. Second, my wife is a Japanese National and attended school in Japan, so I tried to fact check what I could with her before responding.

Let me first clarify what I don’t think happens today.

You wrote:

“In your first comment, you actually paraphrase what I consider to be Hayek’s most powerful argument for markets. No government, no planning agency, and no firm could POSSIBLY know the answers to your good questions about tastes and abilities of the individual. Only the individual could know that. So, a system that “tracks” through education (“You have aptitude to be a blacksmith, so you must go to blacksmith school!) could match that way. Only individuals, choosing along a dozen different dimensions can hope to optimize. I can go to work for IBM, and wear a suit, or go to Apple and wear shorts and a Hawaiian shirt. Which is “better”? People sort, based on complex personal considerations of location, pay, and atmosphere. So, yes, you are right that that diversity of employment options created by firms is a really important thing that we missed.”

I wrote:

“I see this often, but how is this not committing a serious Straw man Fallacy? If I understand the basic argument, it is: socialist governments that try to ‘track individuals through education’ fail, therefore all socialists governments fail. Implying that all socialist governments ‘track individuals’. However, not only is this not part of any current socialist practice, I don’t even think its part of current communist practice. Are there any governments that still do this? Is there anyone defending this position? If not, then either we have to conclude that socialist and communist systems don’t exist, or that ‘tracking individuals’ isn’t a necessary part of them.”

So, just to clarify, I don’t think that government ‘tracking of individuals’ that is a)’deterministic’ (you ‘must’ become this occupation, and in preparation of that government mandate you ‘must’ take this educational track), b) without taking the actions of individuals into account, c) without any regard to prices in local economies is part of socialist government practices.

But, let’s walk through the situation in Japan, and you can explain how an ‘open and free market’ would decrease the ‘tracking of individuals’ there.

To start off, Japan has one of the lowest levels of government expenditures on education of all 30 OECD countries at only 3.5% of GDP.

see: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20070920a3.html

Second, while Japan has one of the highest High School graduation rates in the OECD (see: http://www.data360.org/dsg.aspx?Data_Set_Group_Id=1653), unlike many nations, High School education is not compulsory. As such, much like our university system, you have to apply, be accepted, and pay tuition to attend. (btw, university isn’t free)

That said, I think its market forces, prices and human action, not government planners, that are responsible for the high correlation between what happens after elementary school and before university, and it all pivots around these high school entrance exams.

You see there is a ton of data around which high school has the highest university entrance rates, with schools that have higher university entrance rates either having higher costs or having high test score requirements to enter. Obviously, a high school that had very low costs, and very low test score requirements and very high university entrance exam rates fills up very quickly and then the school must decide on how to balance resources and demand. They could use a lottery, but they don’t. Rather they typically either increase tuition costs or choose the applicants with the highest test scores, or some of both.

As a result, over the years, both aptitude and access to wealth become good predictors of a student’s ability to attend a high school that has a high probability of helping you get into a top university.

But, the market has pushed the system one step further, in fact down to the middle schools. Japanese students (or their parents) tend to choose the middle schools that have the highest acceptance rate into the Top High Schools. Again, there is a ton of data on what middle schools have the highest entrance rates into the High Schools that have the highest entrance rates into the Top Universities.

As better and better teachers go to schools that have the higher aptitude or higher paying students, the market has dug some pretty deep grooves through the Japanese educational system, with the strongest ‘tracks’ extending all the back to the most popular elementary schools.

One note, these correlations are for ‘children likely to go to top universities’ and not, ‘children who are likely to not to go to university’. No one is choosing or planning to send kids to lower correlating schools, in fact, I think these High Schools play a critical role in providing a critical service to the public. Japanese central planning focuses not on who ‘must’ go to which High School in preparation of a predestined vocation, rather educational planners focus on keeping curriculum standards across all schools ‘high’, requiring 6 years English, higher math, world history/geography, international economics, etc, etc.

So, here’s a question, if you don’t like these ‘grooves’ through the educational system. And, if you don’t like the high correlation between university attendance and either scholastics aptitude and/or access to parental wealth at the elementary school stage. And, if you don’t like the level of central planning being done by the government. Perhaps you could walk me through how a ‘free and open’ educational market would improve this situation in Japan? Additionally, perhaps explain how replacing government planners with firm planners is in the interest of those same elementary kids, as your article seemed to suggest.

No more red herring arguments please, can we just stick to the core question of why ‘government planners’ are inefficient when they take into account human actions, prices, limited information, etc, etc, and, in contrast how firm planners are efficient when they do something very similar.

-bruce

Bruce Boston

Jan 17 2008 at 3:07am

Hi Michael,

At first glance, this appeared to be a red herring fallacy response, as you have clearly left all the topical questions unanswered, but looking at this again, maybe we can steer this back on to the topic of the relative efficiencies of both Firms and Government Agencies acting within a market system.

While I am not an expert on the educational system of Japan, any more than I’m an expert on the educational system of America, I’m somewhat a product of that system, having lived in Japan for 6 short years, part of which to attend school. Second, my wife is a Japanese National and attended school in Japan, so I tried to fact check what I could with her before responding.

Let me first clarify what I don’t think happens today.

You wrote:

“In your first comment, you actually paraphrase what I consider to be Hayek’s most powerful argument for markets. No government, no planning agency, and no firm could POSSIBLY know the answers to your good questions about tastes and abilities of the individual. Only the individual could know that. So, a system that “tracks” through education (“You have aptitude to be a blacksmith, so you must go to blacksmith school!) could match that way. Only individuals, choosing along a dozen different dimensions can hope to optimize. I can go to work for IBM, and wear a suit, or go to Apple and wear shorts and a Hawaiian shirt. Which is “better”? People sort, based on complex personal considerations of location, pay, and atmosphere. So, yes, you are right that that diversity of employment options created by firms is a really important thing that we missed.”

I wrote:

“I see this often, but how is this not committing a serious Straw man Fallacy? If I understand the basic argument, it is: socialist governments that try to ‘track individuals through education’ fail, therefore all socialists governments fail. Implying that all socialist governments ‘track individuals’. However, not only is this not part of any current socialist practice, I don’t even think its part of current communist practice. Are there any governments that still do this? Is there anyone defending this position? If not, then either we have to conclude that socialist and communist systems don’t exist, or that ‘tracking individuals’ isn’t a necessary part of them.”

So, just to clarify, I don’t think that government ‘tracking of individuals’ that is a)’deterministic’ (you ‘must’ become this occupation, and in preparation of that government mandate you ‘must’ take this educational track), b) without taking the actions of individuals into account, c) without any regard to prices in local economies is part of socialist government practices.

But, let’s walk through the situation in Japan, and you can explain how an ‘open and free market’ would decrease the ‘tracking of individuals’ there.

To start off, Japan has one of the lowest levels of government expenditures on education of all 30 OECD countries at only 3.5% of GDP.

see: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20070920a3.html

Second, while Japan has one of the highest High School graduation rates in the OECD (see: http://www.data360.org/dsg.aspx?Data_Set_Group_Id=1653), unlike many nations, High School education is not compulsory. As such, much like our university system, you have to apply, be accepted, and pay tuition to attend. (btw, university isn’t free)

That said, I think its market forces, prices and human action, not government planners, that are responsible for the high correlation between what happens after elementary school and before university, and it all pivots around these high school entrance exams.

You see there is a ton of data around which high school has the highest university entrance rates, with schools that have higher university entrance rates either having higher costs or having high test score requirements to enter. Obviously, a high school that had very low costs, and very low test score requirements and very high university entrance exam rates fills up very quickly and then the school must decide on how to balance resources and demand. They could use a lottery, but they don’t. Rather they typically either increase tuition costs or choose the applicants with the highest test scores, or some of both.

As a result, over the years, both aptitude and access to wealth become good predictors of a student’s ability to attend a high school that has a high probability of helping you get into a top university.

But, the market has pushed the system one step further, in fact down to the middle schools. Japanese students (or their parents) tend to choose the middle schools that have the highest acceptance rate into the Top High Schools. Again, there is a ton of data on what middle schools have the highest entrance rates into the High Schools that have the highest entrance rates into the Top Universities.

As better and better teachers go to schools that have the higher aptitude or higher paying students, the market has dug some pretty deep grooves through the Japanese educational system, with the strongest ‘tracks’ extending all the back to the most popular elementary schools.

One note, these correlations are for ‘children likely to go to top universities’ and not, ‘children who are likely to not to go to university’. No one is choosing or planning to send kids to lower correlating schools, in fact, I think these High Schools play a critical role in providing a critical service to the public. Japanese central planning focuses not on who ‘must’ go to which High School in preparation of a predestined vocation, rather educational planners focus on keeping curriculum standards across all schools ‘high’, requiring 6 years English, higher math, world history/geography, international economics, etc, etc.

So, here’s a question, if you don’t like these ‘grooves’ through the educational system. And, if you don’t like the high correlation between university attendance and either scholastics aptitude and/or access to parental wealth at the elementary school stage. And, if you don’t like the level of central planning being done by the government. Perhaps you could walk me through how a ‘free and open’ educational market would improve this situation in Japan? Additionally, perhaps explain how replacing government planners with firm planners is in the interest of those same elementary kids, as your article seemed to suggest.

No more red herring arguments please, can we just stick to the core question of why ‘government planners’ are inefficient when they take into account human actions, prices, limited information, etc, etc, and, in contrast how firm planners are efficient when they do something very similar.

-bruce

LemmusLemmus

Jan 17 2008 at 7:13am

“The educational systems of Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, France, and Japan do exactly this. In order to qualify for university, you have to have been tracked for such at an early age.

If you meant literally “blacksmith,” then no. But the decision on whether a student will go to vocational or academic track is made by the sixth grade, and may be made as early as the 4th grade.”

As far as Germany is concerned, this is not quite correct. It is true that after elementary school children are sorted into different types of schools, only one of which qualifies you for attending a university later. However, if your grades are good enough you can change to such a school as late as after 10th grade.

Mike Munger

Jan 17 2008 at 9:20am

As the Bruce puts it, let us focus on the “core question of why ‘government planners’ are inefficient when they take into account human actions, prices, limited information, etc, etc, and, in contrast how firm planners are efficient when they do something very similar.”

Some claims it appears we agree on:

1. Planning, in the sense that government directs students/workers toward particular employments, based on the government’s tests of aptitude, or need for workers, is a mistake. That would violate fundamental human freedoms, and would also be inaccurate, because tests cannot gauge likely effort or interest. RIGHT?

2. Planning, in the sense of making resource (other than workers, dealt with in #1, above) allocation decisions without the price system, is precarious. Without the information of relative prices about resources scarcities, one cannot plan because one hasn’t the information. Data about totals won’t help: how many apples does it cost to spend two bananas? Only prices can place everything on one scale. RIGHT?

3. Governments agencies, and firms, both suppress the internal workings of the price system. Firms that survive, making positive profits, must (MUST!) be saving enough on costs to make the total use of resources less than doing it through the market. There are MANY firms, competing with each other. When, on the other hand, I walk into the Department of Motor Vehicles, I am entering the national territory of Cuba, or some other fully planned economy. How, how, how would I know if the DMV, or any other government activity, is saving on costs compared to performing the same function through the market? There is no profit test, there is only power.

So, I think the short answer is this, on the “core question”: the similarlity between firms and government is real. William Niskanen, in his public choice classic book, BUREAUCRACY AND REPRESENTATIVE GOVERNMENT, made this argument at length. The difference, though, makes all the difference: firms that are not saving on costs, compared to the market, will go bankrupt and disappear. And firms that make profits are receiving money from consumers who voluntarily are paying the firm for goods or services.

Government agencies that lose money will simply be GIVEN more money; there is no bankruptcy test. And that more money is taken at gunpoint from citizens, by force and against their will.

RIGHT?

Martin Brock

Jan 17 2008 at 12:43pm

Why couldn’t the boss in bunny slippers contract out the answering of these emails too? By firing all of his employees, he erases countless bits of information valuable to the enterprise, but he needn’t reorganize overnight. He could establish long term relationships with other factors without employing them directly.

Maybe, if the boss employs factors directly, he owns all of the emails, and maybe owning all of the emails is valuable to him.

Mike Munger

Jan 17 2008 at 1:55pm

Martin, that is POSSIBLE, and lots of people do it.

But not most. It is easier to buy the supplier than to rely on his goodwill. And it is, more importantly, CHEAPER. Employing factors directly is what makes a firm…a firm.

Martin Brock

Jan 17 2008 at 5:36pm

Highly specialized information can be most valuable to a firm and least valuable outside the firm. This synergistic information is a glue holding the firm together, because each factor’s bit of it is most valuable to the factor only within the firm. I think that’s your point. If so, I’m only reiterating it.

My point is this. The boss effectively owns the synergy, exemplified by his ownership of all of the company’s emails. He doesn’t own each bit, but he owns a margin of value that each bit has only within the firm. An email might be valuable to me only if I may review it to jog my memory, to reconnect it with other information in my memory. The email might be similarly valuable to someone else in the firm, who can similarly connect it to other information. This value belongs to the boss, not to me, because he may fire me and keep it, but if I fire him, I lose it.

Bosses want firms, because they want to own this margin of the value, the value of synergy, and they can effectively own it. It’s legally recognized and forcible property. Other factors want to work for the firm, because they’re worth less outside of it than inside of it.

So we have these capital markets, and they concentrate wealth, because markets are efficient, so investment is essentially a crap shoot. Our asset accumulation is a Geometric Brownian Motion process. We essentially earn a yield on our capital periodically by throwing dice. That’s just a rule of the game we’re playing. The game concentrates wealth, because that’s just the nature of the game, like a game of Monopoly.

People with more capital than most create firms, because they want to own the synergies. It’s not that firms cost less. It’s that other organizations are less attractive to bosses. They aren’t owned, because they can’t be owned. That’s all. The same organization might exist without a boss, but no one could be entitled to the value of the synergy.

The value might exist and contribute to total output even if no one could own it, like the value of an invention I may not or do not patent; however, if the value can be owed, it will be owned by one of these people with capital, because we want to work for firms for various reasons, like we’re just tribal by nature or we want a group health insurance policy or something.

Mike Munger

Jan 17 2008 at 5:49pm

I don’t see that it’s either/or.

There’s no denying you have hit on something important, and it may be the most important reason for many kinds of firms’ existence.

But transactions costs ALSO figure prominently, in a thousand ways that it’s easy to miss.

Your last paragraph is really a THIRD point, one we have missed so far. The same logic, in many ways, could exist for non-profit “firms,” where no one can claim, and so no one could be motivated by, the residual of revenues over costs. And yet we still see something very like firms.

A win for Martin, I’d say.

Martin Brock

Jan 17 2008 at 6:45pm

Non-profits are a good point, but they’re often “non-profit” in name only. I’m thinking of the recent scandal at Oral Roberts University. It’s a non-profit, but the CEO, Richard Roberts, earned nearly half a million a year before a scandal (overblown I thought) led him to resign. Half a million wasn’t enough, Praise the Lord, so he improperly charged vacations for his children, renovations on his house and stuff to church accounts. My sister owns a for profit veterinary practice that’s not nearly so lucrative.

The value of the synergy is the important part. Once it’s there and effectively owned (governed), the nature of hierarchical authority takes over. In principle, states are non-profit organizations, but we all know better than that.

I agree with you, contra Bruce, that markets effectively optimize firms, rather than the decisions of planners within firms. At least, I hope so. If we just start with a planner and have him delegate authority to other planners delegating authority and so until all resources are governed, we don’t get the firms we have. We get something frightfully different.

Bruce Boston

Jan 18 2008 at 2:47am

Hi Michael,

“And that more money is taken at gunpoint from citizens, by force and against their will.”

Well, its only against their will if you reject the ‘Right of Majority Rule’, else its by Democratic ‘Political Will’ by which taxes under penalty of incarceration are collected.

I can’t help but think that the solution remains in the question of ‘Theft’, and how we have to look for ways to reduce the ‘Theft’, or mitigate the risks of Theft, within ‘Majority Rule’ systems for as long as Majority Rule Systems exist.

So, to your Bullet Points.

1) Agreed.

2) Agreed.

3)

“Governments agencies, and firms, both suppress the internal workings of the price system. Firms that survive, making positive profits, must (MUST!) be saving enough on costs to make the total use of resources less than doing it through the market. There are MANY firms, competing with each other.”

i) Agree that firms need to be saving more than they spend else they disappear.

“When, on the other hand, I walk into the Department of Motor Vehicles, I am entering the national territory of Cuba, or some other fully planned economy. How, how, how would I know if the DMV, or any other government activity, is saving on costs compared to performing the same function through the market?”

ii) Well, the total annual budget is well known, you can look it up. As far as a comparison to similar market driven business, I still don’t understand the argument against having a Post Office, while there also being a FedEx, UPS, DHL? Or as in the Japanese Schools, why can’t we have a mixture of Private and Public schools? If the problem is ‘Theft’ then we ought to be advocating for an increased use of ‘Usage Taxes’ where fees and value are more directly linked to keep the system more honest. That said, Firms use the loose linkage between their products to their advantage all the time. Rather than a local park with a full and direct surcharge, taxing surrounding properties that gain direct value in the form of increased value, is what Disneyland does. So, restricting local governments from doing the same, when there is clear and present math, doesn’t seem prudent.

“There is no profit test, there is only power.”

iii) This assumes that there is no third party recourse. Last time I looked the DMV reported into an elected official which is directly responsible to the people. In business there is no such thing. If you don’t like the fact that Walmart stopped selling the diabetic food line that your health requires, you have no third party recourse, and you have to, what negotiators call, use your BATNA (best alternative to a negotiated agreement) with Walmart.

“So, I think the short answer is this, on the “core question”: the similarity between firms and government is real. William Niskanen, in his public choice classic book, BUREAUCRACY AND REPRESENTATIVE GOVERNMENT, made this argument at length.”

iv) agreed, on the sentence. Never read Niskanen.

“The difference, though, makes all the difference: firms that are not saving on costs, compared to the market, will go bankrupt and disappear.”

v) Yes, but I’m not sure this works to the favor of Firms, in fact, I think there are some pretty clear areas in the economy, where this gives them a clear competitive disadvantage when competing with government agencies. If my house value is highly dependent on the services that are provided by my local elementary school, and I have the choice between supporting a public school that has an average lifespan of 50 years, or a private school that has an average lifetime of 25 years, there is a clear economic argument to choose the lower risk alternative for my investment. This doesn’t mean that government sponsored schools don’t disappear, or have unlimited access to funds, because they don’t. This works for almost anything, two banks, one with FDIC insurance one without, which has the competitive advantage? So, again, it doesn’t surprise me that people are voting with their tax promises to choose government solutions over private ones.

“And firms that make profits are receiving money from consumers who voluntarily are paying the firm for goods or services.

Government agencies that lose money will simply be GIVEN more money; there is no bankruptcy test. And that more money is taken at gunpoint from citizens, by force and against their will.

RIGHT?”

vi) Ok, so let’s talk about another advantage that government has: The Right of Majority Rule.

But, before that let’s clean up a few loose ends. First, government agencies are not immune to budgetary restrictions. Second, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a mathematical model that says that governments maximize their ‘take’ at 100% of GDP. Even at 100% of GDP, there is an upper bound. At less that 100% the upper bound is less than 100% of GDP. In fact, I see no reason why we we wouldn’t believe that the equation of how much the public is willing to pay, for how much expected value they will get isn’t currently at equilibrium. If the public thought they could get the same level of services for a lower price, why wouldn’t they use the market or the ballot box to make a choice that was clearly in their economic interest? As such, I think that government budgets are a closed system at close to where they are. Sure they can borrow, and sure they can print more money, but there are very good market forces to tip off the voters to this. **Third, this Country, and many others, have been through bad times before. Markets have failed us, but the Constitution never has.

But, I digress.

As I mentioned above, Theft is clearly a problem, but I’d like to suggest that the only logical response to either the threat of ultimate theft ‘the theft of personal rights’ or the ‘total breakdown of the system’ isn’t opposition to the ‘Right of Majority Rule’ but instead a BATNA for such occurrences. The reason I live in the US is because somewhere in my genealogy someone, if not several people, exercised their BATNA with their governments. Need be, I intend to do the same.

So, now let’s hit the ‘Right of Majority Rule’, first off, government agencies have a huge competitive advantage over private Firms as a result of it. Clearly, given this, I think this is more evidence why government agencies can exist in an open market based on competitive economic advantage, and continue to exist even in a market full of alternative choices.

So, why not just oppose the public’s claim to the ‘Right of Majority Rule’? Putting aside the fact that to oppose the ‘Right of Majority Rule’ is an outright rejection of ‘Democracy’ for the ‘Right of Majority Rule’ is the very definition of ‘Democratic Rule’.

That aside, I think opposition to the ‘Right of Majority Rule’ is illogical, I mean just walk through it.

a) politics is a group sport

b) the risk of loss from the ‘Right of Majority Rule’ approaches 0 once a group is in the majority (51%).

c) the likelihood of gain from the the ‘Right to Majority Rule’ approaches 0 at a number much lower than that of majority (51%).

d) thus, the ‘net benefit’ gained from increasing the size of the group that opposes the ‘Right to Majority Rule’, goes to 0 at a % lower than the majority (51%).

e) the majority of people have a higher gain from the likelihood of benefit than the risk of loss from the ‘Right of Majority Rule’

f) its never in the interest of the majority to give up the ‘Right of Majority Rule’

g) the majority will always vote in its best interest

**h) any decision to do away with the ‘Right of Majority Rule’ would either have to made against the will of the Majority (less than 51%), evoke the ‘Right of Majority Rule’ to make such a decision, or have 100% support to do so.

I can think of nothing more illogical than to bet on this horse, and anyone, or group of people that strongly believes in the opposition of the ‘Right of Majority Rule’, and seeks to build sufficient opposition are doomed to a Sisyphean challenge.

All I can say is get a good BATNA, think of it like government insurance. Besides being an impossible task, giving up Democracy instead of getting Democracy insurance, would be like giving up your house instead of getting catastrophic disaster insurance.

As far as the core question of Why Firms? If we are willing to make the ‘free market’ naturalistic argument that what is ought to be for Firms, then why not make the same argument for government agencies? While Firms have the ability to take higher risks, government agencies clearly have several competitive advantages of their own. Wouldn’t we expect entities with unique competitive advantages to continue to exist?

-bruce

D.F. Paulaha

Jan 18 2008 at 12:58pm